Transcription

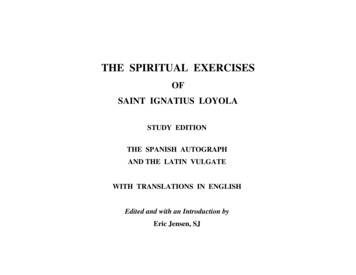

THE SPIRITUAL EXERCISESOFSAINT IGNATIUS LOYOLASTUDY EDITIONTHE SPANISH AUTOGRAPHAND THE LATIN VULGATEWITH TRANSLATIONS IN ENGLISHEdited and with an Introduction byEric Jensen, SJ

INTRODUCTIONA return to the sources of our Christian faith has longbeen recognized as indispensable. So also with our variousChristian spiritualities. It was a return to the sources ofIgnatian spirituality that led Jesuits back to the Spanish“Autograph” text of the Spiritual Exercises. We have nomanuscript of the Spiritual Exercises composed by Ignatius.We have, rather, a copy with thirty-seven corrections, at leastthirty-two of them in Ignatius’ own handwriting (hence thedesignation “Autograph”) It is written is somewhat archaicSpanish, and salted with many Latin words. Prior to thenineteenth century, the authorized Latin version of the SpiritualExercises had been in use almost universally. Officiallyapproved by Pope Paul III in 1548, and known as the“Vulgata,” it had been the basis of most new translations intoother languages.Though vernacular translations from the SpanishAutograph have since eclipsed those from the Latin, many ofus continue to use Latin terms, such as “magis”, “suscipe”, or“agere contra”, and to refer to the “Contemplation onAttaining the Love of God” as the Contemplatio ad amorem, orsimply as the Contemplatio (or, in French, l’Ad amorem).To speak of a return to the sources implies that theremay be more than one source. The modern translations of theSpiritual Exercises in use today actually have several sources.This is made clear in the magnificent work of scholarshipproduced by Cándido de Dalmases, SJ, (bringing to completionthe work begun by José Calveras, SJ) in Volume 100 of theMonumenta Historica Sociatatis Iesu.2 There, laid out inparallel columns, are the texts of the Spanish Autograph (A)and the Authorized Latin Vulgate (V) on the left-hand pages,and, on the right-hand pages, the texts of two other Latintranslations: Versio Prima A of 1541 (designated P1) andVersio Prima A of 1547 (designated P2). These four originaltexts (Textus Archetypi) constitute the main sources of theSpiritual Exercises.Just before the middle of nineteenth century,translators of the Vulgate had begun to acknowledge theexistence of the Spanish Autograph. In 1835, Johann PhilippRoothaan, General Superior of the Society of Jesus, publishedhis own literal Latin translation of the Autograph, together withthe Spanish text, to encourage a return to this source. Thirteenyears later, Charles Seager, in a new English translation of theVulgate, made use of Roothaan’s work.1Building upon the foundations laid in the Monumenta,Maurice Giuliani, SJ, published in a single volume thecarefully edited works of Saint Ignatius Loyola.3 There thesource texts of12See p. 19 of his preface to The Spiritual Exercises ofSt. Ignatius of Loyola, Translated from the Authorized Latin;with Extracts from the Literal Version and Notes of the Rev.Father Rothaan [sic], Father-General of the Company of Jesus.This is the first American Edition, published by John Murphy& Co., Baltimore, 1849 (it lacks section numbers, which werenot introduced until 1928).MHSJ 100, MI 1, Monumenta Ignatiana: SanctiIgnatii de Loyola Exercitia Spiritualia, The Historical Instituteof the Society of Jesus (IHSI), Rome,1969.3Ignace de Loyola: Écrits, traduits et présentés sous ladirection de Maurice Giuliani, SJ, Collection Christus No. 76,Textes, Desclée de Brouwer, Bellarmin, 1991. Included are239 of Ignatius’ 6,815 letters, each introduced and annotated.1

Paris, he would have presented his notes on the Exercises notin Spanish but in Latin, the language of the ecclesiasticalauthorities.5 While we do not have these early notes, what wedo have is the Latin Versio Prima of 1541 (P1).the Exercises are laid out in three columns with Frenchtranslations of the Autograph, the Versio Prima of 1547 (P2),and the Vulgate, with a fourth column of commentary. Whilethis new arrangement makes comparison of three ancient textsof the Exercises somewhat easier, especially with the aid of thecomments in the fourth column, the French translation oftenveils the nuances in the Spanish or Latin, as the editor readilyadmits.On the first page of this manuscript, in his own hand,Ignatius has written, in a mixture of Spanish and Latin, “Todosexercitios breviter en Latín.” Dalmases demonstrates that whatthe Latin word breviter (briefly, concisely) implies is not ashorter version of the Exercises found in the Autograph, but atext that concisely contains only the Exercises. Ignatius thusmeans to distinguish this original text (textus archetypus) fromthe “adapted texts” (textibus accommodatis), texts with manyglosses and amplifications, adapted by or for someone actuallygiving the Exercises, that is, orally accompanying or directinganother through the experience of praying them.6 Though thedate 1541 has been written on the manuscript (by someoneother than Ignatius), Dalmases believes that this Latin versionwas probably made by Ignatius himself, and that it originatesfrom the earlier part of the years he spent in Paris (15281535).7What becomes clear from the work of both Dalmasesand Giuliani is that there is no single text of the Exercises towhich we can point as the sole source, though the Autograph isthe text that holds pride of place. In summing up his fifty-fivepage Latin introduction to the four original texts, Dalmasesdraws a number of conclusions, among them that, tothoroughly interpret the mind of Ignatius, it is necessary tohave recourse to the Spanish text, since the mind of the authoris to be found in the text written by him, more than in anyversion however perfect.4 While one may therefore be temptedto say that in the Autograph we find the ipsissima verba, thevery words of Ignatius, and the conocimiento interno or interiorworkings of his mind and heart, we need to remember thatÍñigo de Loyola was a Basque; Castilian was his secondlanguage, and so at one remove from his heart if not from hismind.The manuscript was emended by some of Ignatius’Jesuit companions, and a new Latin version, incorporating theircorrections, was produced–the Versio Prima of 1547 (P2)–forapproval by the pope. This second very literal Latintranslation, though more accurate, was lacking in elegance, andso, at the very time that it was being completed, yet a thirdLatin version, the Vulgate, was begun in 1546 by a youngFrench Jesuit, André des Freux (or Frusius, to use the LatinIt helps also to recall that, when Ignatius in Paris wasleading Pierre Favre through an experience of the Exercises, hewas certainly not doing so in Spanish or French (Favre was aSavoyard with his own French dialect), but rather in thecolloquial Latin that was in use among international students atthe University of Paris at the time. Likewise, when Ignatiushad to defend himself and his teachings before the Inquisitor of5MHSJ MI 1, 108-109.MHSJ MI 1, 108.7MHSJ MI 1, 113; Giuliani, Écrits, 38.64MHSJ, MI 1,135, conclusion No. 4.2

form of his name). These last two Latin versions of thepapal authorities and approved in 1548.Exercises were submitted together to thethe “definitive text” of the Spiritual Exercises.13 He based thisdescriptive title on the hypothesis that des Freux’s translationwas done from a later copy of the Autograph with correctionsand changes made by Ignatius, a text now lost.14 Giulianirejects this claim, referring to Dalmases’ 1986 study showingthat the hypothesis does not stand up to critical examination.15Giuliani states that it is not possible to know whatsources were used by des Freux when he made the Vulgatetranslation. Did he have access to the Spanish Autograph or toother Spanish manuscripts now lost? Did he make use of theLatin Versio Prima of 1541 (P1), or was the Latin version of1547 (P2) completed and in his hands before he finished hisown translation in this same year? It seems that no one cansay.8 The fact that des Freux follows P2's correction in theorder of the points in The Mysteries of the Cross (Sp. Ex. 297)9 might be evidence that he had the completed version of P2 inhis hands at this point in his work. Delmases, however, makesnote of this change and gives the order of the points prior to thecorrection, without saying who made the correction to P2 orwhen it was made.10 Sp. Ex. 297 is not listed among theemendations he attributes to Juan Alfonso de Polanco, butDalmases admits that there are other changes which could bethe work of a copyist or of Polanco or of some other unknownperson.11Guy attempts to bolster his argument for the Vulgate’sprivileged position with the fact of the text’s papal approbation.Moreover, it was only this approved Vulgate text that Ignatiuschose to have printed. Thus, he says, it became the definitiveand normative text.16 No new emendations were to be made tothe text since it had been surrendered to Christ and placedunder the protection of his Church.17 But, as Giuliani stresses,both the final Latin translations (P2 and the Vulgate) had beenapproved by the pope in 1548, and so, in Ignatius’ eyes, bothhad the same authority.18If the Vulgate was to be the preferred text, as Polancoin his preface says that it must (“Visa est praeferenda”),19 thiswould appear to be for reasons of style rather than accuracy oftranslation. It is a style that Giuliani calls recherché–affectedor mannered–and occasionally lacking concern for fidelity inthe translation.20 While, during the final seven or eight yearsIn recent times, interest in the Vulgate has continued togrow. Lewis Delmage, SJ, produced an American translationof the Vulgate into contemporary English in 1968.12 Nineyears before Giuliani’s Écrits appeared, Jean-Claude Guypublished a French translation of the Vulgate, which he called13Saint Ignace de Loyola: Exercices spirituels, Textedéfinitif (1548), Éditions du Seuil, 1982.14Guy, 16-17.15Giuliani, Écrits, 39, note 15.16Guy, 17.17Guy, 18-19.18Giuliani, Écrits, 39.19Giuliani, 39.20Giuliani, 39.8Giuliani, Écrits, 38.MHSJ MI 1, 360-361.10MHSJ MI 1, 360, note on P2, lines 55-74.11MHSJ MI 1, 115.12The Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius Loyola,Joseph F. Wagner, Inc., Publishers, New York, 196893

of his life, Ignatius himself may have continued to employ themore literal Latin version of 1547 (P2) as well as the Vulgate,the Vulgate soon became the only Latin version in use, thanksto the insistence of Polanco, Ignatius’ secretary and closecollaborator.21The Source-Texts (A, V, P1, and P2) enable us toappreciate anew the mind of Ignatius, the mind that struggledover the years to universalize the experience of God working inhis life, the mind that freely surrendered his work and that ofhis translators into the hands of Christ and the Church, and thatno doubt smiles upon new attempts to render the Exercises intoother languages.As for the English translations of the source textsemployed here, Elder Mullan’s literal one of the Autograph,made in 1909 and published in 1914, has already been used toadvantage by David L. Fleming, SJ, in his several editions ofthe Exercises,23 and is used here with the kind permission ofFather John W. Padberg, SJ, Director of The Institute of JesuitSources in St. Louis, Missouri. The English translation of theVulgate, by Pierre Wolff,24 is used with the graciouspermission of Suann Fields of Liguori Publications. Wolff’scommentary, not included here, is very insightful and practical,and he occasionally makes reference to some of the differencesto be found in comparing the Latin and Spanish texts. Hepoints out, to cite but one instance, that the word “indifferent”(indiferentes), which is often given much prominence andimportance in studies of the Principle and Foundation (Sp. Ex.23), is not to be found in the Latin Vulgate.25Giuliani includes P2 in his Écrits, and it is interesting tonote that, in translating the preparatory prayer (Sp. Ex. 46),which must never be changed (Sp. Ex. 46 and 105), both P2and the Vulgate reduce its three elements to two: “intenciones,actiones y operaciones in the Autograph become intentiones etactiones in P2, and vires atque operationes in the Vulgate.22Both translators of the Autograph cast light on how theyresolved the seeming redundancy in the Spanish text, and it ishelpful to be able to compare them. As for including P2 in ourstudy edition, however, this would have required translating itinto English, since I know of no extant English translation(Giuliani’s is its first into French). For most practical purposesin a work such as this, there are only two source-texts of theExercises to return to: the Spanish Autograph, which hasdominated the field for the past 150 years, and the LatinVulgate, which is once again finding favour.George Ganss, SJ, published a translation of theAutograph which also has a very helpful scholarlyintroduction, and it is there that I was first alerted to anotherdifference between the Autograph and the Vulgate. In thefamous prayer, “Take and Receive” (Tomad, Señor, y recibid,Sp. Ex. 234), the final phrase of the Spanish begins with thewords dadme vuestro amor y gracia. It is usually translatedas “give me your love and your grace,” whereas the LatinVulgate says, Amorem tui solum cum gratia tua mihi dones,23Most recently in Draw Me into Your Friendship: ALiteral Translation and A Contemporary Reading, The Instituteof Jesuit Sources, St. Louis, MO,1996.24The Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius, Translatedand with Commentary by Pierre Wolff, Triumph, Liguori,MO, 1997.25Wolff. See the text, 11, and the commentary, 110.21The Autograph continued to be used in Spain, whereit was printed in 1615. An Italian translation of the Vulgatewas printed in 1555, while Ignatius was still living. See Guy,17.22MHSJ MI 1, 184-185.4

“Give me only love of yourself along with your grace.”26Wolff puts this succinctly as: “Grant me only the grace to loveYou.”27 One asks not for still more love but for the grace torespond to God’s love.after papal approval of des Freux’s translation, show how farfrom perfect this “definitive” text was seen to be. Thesentences needing clarification are marked with an asterisk inthe Monumenta, and the suggested rewording appears there infootnotes. So that these suggestions would not be lost whenthe scholarly apparatus was removed for this edition, the wordsneeding clarification have been underlined here and theclarifications have been included in square brackets within theLatin text itself.The opening Latin word of this prayer, Suscipe, has arich history which goes back at least to Virgil, who usessuscipere as meaning to take up a new-born child from theground and to acknowledge it as one’s own.28 It could perhapsbe rendered as Take under your protection.29 Charles Seageravoids the ambiguities in the English verb take by translatingthe Latin phrases this way: “Receive, O Lord, my wholeliberty. Accept my memory, understanding, and whole will.”30Delmage, however, opts for “Take.Receive,”31 and Wolff for“Take. Accept.”32Comparing the Autograph with the Latin versions, webecome aware, says Giuliani, of a convergence of diverseexpressions, and with Ignatius we recognize a singleinspiration behind these efforts to translate his work. Ignatiusnever interfered in the process of translation, and showed a raregift for self-effacement, leaving the field free to whatever thetext might open up in the experience of the one engaged inmaking the Exercises.34Though any changes to the authorized text of theVulgate were forbidden, many important clarifications weresuggested by the Fifth General Congregation of the Society ofJesus in 1598.33 Their number and extent, made just fifty yearsThe present edition of the Exercises does not attempt toreplace the work of either Dalmases or Giuliani. It hopesrather to supplement it by presenting the original texts of theSpanish Autograph and the Latin Vulgate (minus footnotes andcritical apparatus) reproduced from the Monumenta, togetherwith good, literal English translations of each. It offers anyonewith an interest in these texts, as well as the scholar and studentof the Exercises, a simple way of comparing the Autograph andVulgate, without having to juggle two separate English editionsof the Exercises, together with the hefty tome of theMonumenta to which they may not always have easy access.For those whose focus is primarily on comparing thetranslations, but who may be interested in seeking out the26The Spiritual Exercises of Saint Ignatius, ATranslation and Commentary by George E. Ganss, SJ, TheInstitute of Jesuit Sources, St. Louis, MO, 1992, 184, endnote122.27Ganss, 60.28Cassell’s New Latin Dictionary, 1959, s.v.“Suscipio.”29Collins Latin Gem Dictionary, 1957, 1969, s.v.“Suscipio.”30Seager, 130.31Delmage, 122.32Wolff, 60.33See the first of the clarifying footnotes, which makesreference to the ratification of the amendments by SuperiorGeneral Claudius Aquaviva, 25 June, 1598, Monumenta,144.34Giuliani, 39.5

Spanish and Latin behind certain English words or phrases, theoriginal languages are readily available here.It was the late Walter Farrell, SJ, of Manresa JesuitRetreat House, Bloomfield Hills, MI, who loaned Sister KathieVolume 100 of the Monumenta to work with. RobertGeisinger, SJ, Procurator General of the Society of Jesus,Rome, put us in touch with James Pratt, SJ, AdministrativeDirector of the Historical Institute of the Society of Jesus,Rome, whose encouragement helped us bring this project toterm. The texts from the Monumenta are, of course, used withpermission. Finally, I wish to thank John W. Padberg, SJ,Director of the Institute of Jesuit Sources, St. Louis, for hissuggestions and his continuing encouragement.The initial heading above the Spanish Autograph hasbeen changed from Latin to Spanish for this Study Edition. Asfor the bracketed signs [1r], [1v], etc., which appear within theSpanish and Latin texts, these indicate each numbered leaf of amanuscript: 1r 1 recto folio or “on the front of leaf 1,” and 1v 1 verso folio or “on the back of leaf 1.” It seemed best not toremove them. I trust that any accidental changes caused bythe scanning have been detected and corrected. The editorwould appreciate being informed of any that may have beenmissed.Eric Jensen, SJLoyola HouseIgnatius Jesuit CentreGuelph, Ontario, CanadaN1H 6J2ejensen@ignatiusguelph.caA special debt of gratitude is owed to Kathie Budesky,IHM, of Visitation North Spirituality Center, Bloomfield Hills,Michigan, who eagerly undertook the scanning of the texts andtheir preparation for publication; without her generosity thiswork would not have been undertaken; without her ingenuity indealing with the technical difficulties it would not have beencompleted.6

THE SPIRITUAL EXERCISESOFSAINT IGNATIUS LOYOLATHE SPANISH AUTOGRAPHAND THE LATIN VULGATEWITH TRANSLATIONS IN ENGLISH

TEXTO AUTÓGRAPHO( A)THE SPANISHAUTOGRAPHVERSIO VULGATA( V)THE LATIN VULGATE1548[f.1r]TRANSLATION BYELDER MULLAN, S.J.[f.1r]TRANSLATION BYPIERRE WOLFFJHSIHSIHS[1] ANNOTACIONES PARATOMAR ALGUNA INTELIGENCIAEN LOS EXERCICIOSSPIRITUALES QUE SE SIGUEN, YPARA AYUDARSE, ASÍ EL QUELOS A DE DAR, COMO EL QUELOS A DE RESCIBIR[1] ANNOTATIONSto give some understanding of thespiritual exercises which follow, andto enable him who is to give and himwho is to receive them to helpthemselves.[1] ANNOTATIONES QUAEDAMALIQUID ADFERENTESINTELLIGENTIAE AD EXERCITIASPIRITUALIA QUAESEQUUNTUR, UT IUVARI POSSITTAMIS, QUI EA TRADITURUSEST, QUAM QUI ACCEPTURUS[1] ANNOTATIONSSome annotations that bring anunderstanding of the followingSpiritual Exercises, and that mighthelp the one who gives them as well asthe one who makes them1a annotación. La primera annotaciónes, que por este nombre, exerciciosspirituales, se entiende todo modo deexaminar la consciencia, de meditar,de contemplar, de orar vocal y mental,y de otras spirituales opperaciones,según que adelante se dirá. Porque asícomo el pasear, caminar y correr sonexercicios corporales ; por la mesmamanera, todo modo de preparar ydisponer el ánima para quitar de sítodas las affectiones desordenadas y,después de quitadas, para buscar yhallar la voluntad diuina en ladispositión de su vida para la salud delánima,sellamanexerciciosespirituales.First Annotation. The first Annotationis that by this name of SpiritualExercises is meant every way ofexamining one's conscience, ofmeditating, of contemplating, ofpraying vocally and mentally, and ofperforming other spiritual actions, aswill be said later. For as strolling,walking and running are bodilyexercises, so every way of preparingand disposing the soul to rid itself ofall the disordered tendencies, and,after it is rid, to seek and find theDivine Will as to the management ofone's life for the salvation of the soul,is called a Spiritual Exercise.Prima est annotatio, quod ipse nominespiritualium exercitiorum intelligiturmodus quilibet examinandi propriamconscientiam ; item meditandi,contemplandi,orandisecundummentem et vocem ; ac postremo aliasquascunque spirituales operationestractandi, ut dicetur deinceps. Sicutenim deambulare, iter facere et currereexercitia sunt corporalia ; ita quoquepraeparare et disponere animam adtollendas affectiones omnes amvoluntatem Dei circa vitae suaeinstitutionem et salutem animae,exercitia vocantur spiritualia. [1v]First Annotation: By the words"Spiritual Exercises," we shouldunderstand any method of examiningour own conscience, and also ofmeditating, contemplating, prayingmentally and orally, and finally ofdealing with any other spiritualactivities, that will be referred to lateron. In the same way that walking,traveling, and running are corporalexercises, so preparing and disposingthe soul to remove all inordinateattachments and, after they have beenremoved, searching and finding thewill of God about the management ofone's life and the salvation of the soulare spiritual exercises.[2] 2a. La segunda es, que la personaque da a otro modo a orden parameditar o comtemplar, deue narrarfielmente la historia de la talcomtemplatiónomeditación,[2] Second Annotation.l The second isthat the person who gives to anotherthe way and order in which tomeditate or contemplate, ought torelate faithfully the events of such[2] Secunda est, quod ille, qui modumet ordinem alteri tradit meditandi sivecontemplandi, fideliter narrare debetmeditationis seu contemplationishistoriam, percursis obiter dumtaxat[2] Second Annotation: The personwho gives to another a method andorder for meditation or contemplationmust faithfully narrate the story to bemeditated on or contemplated by1

discurriendo solamente por lospunctos con breue o sumariadeclaración ; porque la persona quecontempla, tomando el fundamentoverdadero de la historia, discurriendoy raciocinando por sí mismo, yhallando alguna cosa que haga unpoco más declarar o sentir la historia,quier por la raciocinación propria,quier sea en quanto el entendimientoes illucidado por la virtud diuina, [1v]es de más gusto y fructo spiritual, quesi el que da 1os exercicios hubiesemucho declarado y ampliado elsentido de la historia ; porque no elmucho saber harta y satisfaze alánima, mas el sentir y gustar de lascosas internamente.Contemplation or Meditation, goingover the Points with only a short orsummary development. For, if roundwork of the narrative, and,discussing and considering forhimself, finds something which makesthe events a little clearer or bringsthem a little more home to him-whether this comes through his ownreasoning, or because his intellect isenlightened by the Divine power--hewill get more spiritual relish and fruit,than if he who is giving the Exerciseshad much explained and amplified themeaning of the events. For it is notknowing much, but realising andrelishing things interiorly, thatcontents and satisfies the soul.punctis illius praecipuis, et adiectasolum brevi declaratiuncula ; ut is, quimeditaturus est, accepto veritatishistoricaeprimumfundamento,discurrat postea et ratiocinetur perseipsum. Ita enim fiet, ut dum aliquidinvenerit, quod elucidationem velapprehensionem historiae aliquantomaiorem praebeat (sive ex discursuproprio, sive ex divina mentisillustratione id contingat) ; gustumdelectabiliorem et uberiorem fructumpercipiat, quam si res ipsa ei ab alterodiffusius narrata et declarata esset ;non enim abundantia scientiae, sedsensus et gustus rerum interiordesiderium animae explere solet.merely passing through the principalpoints and adding only briefclarifications; so that the one who isgoing to meditate, after having firstaccepted the basis of the historicaltruth, will then go over it and considerit by himself. Thus it would happenthat when he finds something thatwould offer a greater elucidation orapprehension of the story (whether ithappens through his own reflection ora divine inspiration in his mind), hewill harvest a more delightful taste andmote abundant fruit than if the samething had been more extensivelynarrated and explained by someoneelse. It is not, indeed, the abundanceof knowledge, but the interior senseand taste of things, that usuallysatisfies the desire of the soul.[3] Tertia est, quod cum insequentibusomnibusexercitiisspiritualibus utamur actibus intellectusquando discurrimus, [2r] voluntatisvero quando afficimur ; advertendumest in operatione, quae precipue estvoluntatis, dum voce aut mente cumDomino Deo vel sanctis eiuscolloquimur, maiorem exigi a nobisreverentiam, quam dum per usumintellectus circa intelligentiam potiusmoramur.[3] Third Annotation: Because, in allthe following Spiritual Exercises, weuse acts of intellect when we reflectand acts of will when we reactaffectively, we should be aware that,especially in the activity of the will,when we are vocally or mentally inconversation with God, the Lord, orHis saints, a greater reverence isdemanded from us than when weremain speculating by the use of theintellect.1The word Annotation does not occur in theoriginal after the first time. The same is true ofsimilar cases in the Mss.[3] 3a. La tercera. Como en todos sdelentendimiento discurriendo y de los dela voluntad afectando ; aduertamosque en los actos de la voluntad,quando hablamos vocalmente omentalmente con Dios nuestro Señor ocon sus santos, se requiere de nuestraparte mayor reuerencia, que quandovsamosdelentendimientoentendiendo.[3] Third Annotation. The third: As inall the following Spiritual Exercises,we use acts of the intellect inreasoning, and acts of the will inmovements of the feelings: let usremark that, in the acts of the will,when we are speaking vocally ormentally with God our Lord, or withHis Saints, greater reverence isrequired on our part than when we areusing the intellect in understanding.[4] 4a. La quarta. Dado que Para los [4] Fourth Annotation. The fourth: [4] Quarta est, quod licet exercitiis [4] Fourth Annotation: Four Weeksexercicios siguientes se toman quatro The following Exercises are divided sequentibusassignenturquatuor are given to the Exercises that follow,2

semanas, por corresponder a quatropartes en que se diuiden los exercicios; es a saber, a la primera, que es laconsideración y contemplación de lospecados ; la 2a es la vida de Xponuestro Señor hasta el día de ramosinclusiue ; la 3a la passión de Xponuestro Señor ; la 4a la resurrectión yascensión, poniendo tres modos deorar : tamen, no se entienda que cadasemana tenga de necessidad siete oocho días en sí. Porque como acaesceque en la primera semana vnos sonmás tardos para hallar lo que buscan,es a saber, contrición, dolor, lágrimaspor sus pecados ; asimismo como vnossean más diligentes que otros, y másagitados o probados de diuersosspíritus ; requiérese algunas vezesacortar la semana, y otras vezesalargarla, y así en todas las otrassemanas siguientes, buscando lascosas según la materia subiecta ; peropoco más o menos se acabarán en xxxdías. [2r]into four parts:First, the consideration andcontemplation on the sins;Second, the life of Christ ourLord up to Palm Sunday inclusively;Third, the passion of Christour Lord;Fourth, the resurrection andascension, with the three Methods ofPrayer.Though four weeks, to correspond tothis division, are spent in theExercises, it is not to be understoodthat each Week has, of necessity,seven or eight days. For, as it happensthat in the First Week some are slowerto find what they seek--namely,contrition, sorrow and tears for theirsins--and in the same way some aremore diligent than others, and moreacted on or tried by different spirits; itis necessary sometimes to shorten theWeek, and at other times to lengthenit. The same is true of all the othersubsequent Weeks, seeking out thethings according to the subject matter.However, the Exercises will befinished in thirty days, a little more orless.hebdomadae, totidem exercitiorumpartibussingulaesingulisrespondentes ; videlicet, ut in primahebdomada fiat consideratio depeccatis ; in secunda de Domini nostriIesu Christi vita usque ad ingressumeius in Hieresalem die DominicaPalmarum ; in tertia de passioneeiusdem ; in quarta de resurrectione etascensione, adiectis tribus orandimodis ; non tamen ita accipiendae suntdictae hebdomadae, ut necesse situnamquanque continere septem velocto dies. Cum enim contingat aliosaliis tardiores vel promptiores esse adconsequendum id, quod quaerunt ;putainprimahebdomadacontritionem, dolorem et lachrimas[2v] de peccatis suis ; aliquos etiamplus aut minus agitari probariquevariisspiritibus:expeditnonnumquam succidi hebdomadam*[contrahi hebdomadam] quamcunquevel extendi, iuxta materiae subiectaerationem.Solet tamen totumexercitiorum tempus triginta dierum,aut circiter, spatio concludi.each one corresponding to each part oftheExercises.Namely,theconsideration of Sins is made duringthe First Week, that of the life of JesusChrist our Lord up to His entrance intoJerusalem for Palm Sunday during theSecond Week, that of the passionduring the Third,

Ignatian spirituality that led Jesuits back to the Spanish “Autograph” text of the Spiritual Exercises. We have no manuscript of the Spiritual Exercises composed by Ignatius. We have, rather, a