Transcription

Fighting in the StreetsTesting Theory on Urban WarfightingKeywords: Urban Warfare, Alice Hills, Stalingrad, Grozny, Mogadishu.Viktor VillnerSupervisor: Alastair FinleySwedish Defense UniversityInternational Master’s Programme in Politics and War

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityMaster’s Thesis2017-05-24AbstractThis paper sets out to examine why it is that combat in urban environments is so deadly andcasualty-heavy for conventional militaries, even when those militaries hold a technologicaland/or numerical advantage. The paper aims to test the theory of Alice Hills through a structured,focused comparison on three cases of urban warfighting. The paper examines the battle ofStalingrad 1942-1943, the battle of Mogadishu 1993 and the first battle of Grozny in 1994.Support for Hills theory is found in what she argues is a pre-modern type of combat that is slowgoing and relies upon ground forces as well as the equalization of technological advantagesthrough improvised adaptation of older and/or less than ideal equipment. The paper highlightsthe need for intelligence in urban operations, especially human intelligence, as a potentionalfurther development of Hills theory.Introduction . 3Previous Research . 4Urban Operations. 5Toward a Theory on Urban Warfighting . 7The Nature of Urban War . 7The Presence of Non-combatants . 7The Promise of Technology . 8A Framework for Testing Assumptions . 9Methodology . 11Structured, Focused Comparison. 11Ontological and Epistemological Considerations . 15Alternative Methodological Approaches . 16Empirical Material . 18Case Studies . 20Stalingrad . 20Conclusions. 24Mogadishu . 25Conclusions. 29Grozny . 31Conclusions. 34Conclusions . 36References . 40[2]

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityMaster’s Thesis2017-05-24IntroductionThe NVA were dug in and waiting for us on the other side of the street. They occupied first- and second-floorwindows, and many of the NVA were on the roofs. Several automatic weapons raked the street from our leftflank, from the tower that protected the eastern entrance to the Citadel. And I ran, and ran, and ran, and I gotnowhere fast.There was no place to hide; I was shit outta luck.Nicholas Warr (1997) p.105Military operations in cities across the globe have taken many lives. Infamous battles such asStalingrad, Berlin, Hue, Mogadishu, Grozny and Fallujah serve as examples of some of the mostdifficult fighting in history. The above quote is from Nicholas Warr, a former U.S. Marine Corpslieutenant who served during the battle of Hue 1968 in the Vietnam War. He saw most of hisplatoon wiped out by entrenched North Vietnamese Army soldiers during a battle that lasted overa week. A battle of house-by-house fighting against an opponent that when in risk of beingoverrun kept withdrawing further and further back, into more and more entrenched positions.So, why is it that urban warfighting is so difficult and fraught with casualties for conventionalmilitaries, despite technological and/or numerical advantage? Alice Hills tries to address thispuzzle in her book Future War in Cities. Her theoretical contribution provides a framework forpolicy, doctrine and future research. But her theory remains untested. She provides brief casestudies but these do not critically examine the assumptions Hills makes regarding the nature ofurban combat and the role of technology in urban operations. The purpose of this paper is to testHills theory and its explanatory value for the research problem described above through threecase studies. By examining Hills theory, it is possible to establish its viability as an explanationfor the difficulty and deadliness of urban warfare.Hills, as well as many others, have argued that the world is increasingly becoming urbanized(Hills 2004:4, McGuiness 2000:1). This shift will only magnify the problem that urban warfarerepresents. The current Western approach to urban warfare is one of avoidance (Hills 2004:40-[3]

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityMaster’s Thesis2017-05-2441). While this might work, any capable enemy will soon follow the dictum of Sun Tzu that"what is of supreme importance in war is to attack the enemy's strategy" (Sun Tzu [transl.Griffith] 1963:77). As Western forces and coalitions avoid cities the enemy will concentrate justthere, where the western strategy is weakest. As such, this problem is of utmost importance forpolicy, strategy and doctrine. Furthermore, as urbanization increases more and more noncombatants risk becoming collateral damage in devastating urban operations. Mega-cities, suchas Tokyo, Seoul and New York, are home to tens of millions of people. Any warfighting in thesecities might be more devastating than anything previously seen. For social science, this problemis important in understanding the role of civilians in combat, in understanding how to avoidcollateral damage and in understanding how urban warfare might look in the 21st century. Aspeace cannot be promoted without an understanding of war so cannot urban operations beavoided or diminished without an understanding of urban warfighting.Previous ResearchSurprisingly little research has been done on the characteristics of urban operations consideringthe infamy with which some battles are regarded. Alice Hills is one of the more prolific writersin the field. In addition to the book Future War in Cities she has written articles on urbanoperations and post-conflict policing. The RAND corporation has published several books abouturban operations. Scott Gerwher and Russell Glenn explore the role of deception within urbanoperations in their book Art of Deception (2000) finding that deception has a high degree ofeffectiveness in the urban environment which is suitable for ambushes and flanking. SeanEdwards, also of the RAND corporation, explores three cases of recent U.S. urban operations inhis book Mars Unmasked (2009) finding that the urban environment is unique both in physicalityand political aspects. He highlights the importance of information warfare in urban operationswhile certain aspects relating to such operations remain unchanged. David Kilcullen explores theurban environment and urban operations in his book Out of the Mountains (2013). Highlightingthe changing nature of war and the border between combatant and noncombatant Kilcullen uses abody politic metaphor in imagining the city as an ecosystem that must be accounted for during anoperation. Anthony King explores how Special Forces tactics in urban operations aredisseminated in the U.S. military among non-specialized infantry units in his 2016 article “CloseQuarters Battle: Urban Combat and ‘Special Forcification’”.[4]

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityMaster’s Thesis2017-05-24Christina Patterson has highlighted the role of infrastructure and how urban operations affect thecivilian population by destruction, or preservation, of critical infrastructure in her paper “LightsOut and Gridlock: The Impact of Urban Infrastructure Disruptions on Military Operations andNon-Combatants” (2000). Patterson’s paper was published by the Institute for Defense Analysiswhich has also published Murray Williamsons paper “War and the Urban Terrain in the TwentyFirst Century” (2001) which explores historical cases of U.S. military engagement and the role ofurban operations within them. Two papers from the U.S. Army War College explores the U.S.preparedness for urban operations: “United States Army Special Forces – The 21st CenturyChallenge” by Lt. Col. Matthew McGuiness (2000) and “The United States Armys Preparednessto Conduct Urban Combat: A Strategic Priority” by Lt. Col. David Wood (1997).In contrast to these more mainstream researchers is Stephen Graham. In his book Cities underSiege (2013) Graham uses a combination of Marxist and post-structuralist perspectives to arguethat oppressive mechanisms and methods of population control are perfected in low-intensityconflicts in the global south. These are then imported to the industrial cities of the north where itis used to control minority populations. He argues that this is a new type of militarized urbanismthat conflates liberalism, nationalism and rural suspicion of urban cosmopolitism to createdangerous Others.Urban OperationsCities can be regarded as special terrain. It has the same multidimensional battlespace thatmountainous terrain has as well as the restrictions on movement and maneuver jungle terrain hasand it has similar logistical requirements as operations in desert terrain (Gerwher & Glenn2000:9). But it is unique in that it is a human environment, a "complex manmade terrainsuperimposed on existing natural terrain [.]" (Hills 2004:7). The presence of humans, ofnoncombatants, is frequently high-lighted as the defining feature of urban environments (Hills2004:7-8, Gerwher & Glenn 2000:8-9, McGuiness 2000:1). Alice Hills argues that "urbanoperations are special because their environment explicitly shapes them" (Hills 2004:8).[5]

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityMaster’s Thesis2017-05-24Urban environments also contain significant infrastructural elements. As Christina Pattersonhighlights these are sometimes crucial to our daily functioning and for an urban area to run as itshould (Patterson 2000:1). These services can be as impactful as getting caught in a fire-fight.Without electricity, not only lights cease to function but hospital equipment; coolers and freezersfor perishables; water treatment facilities; and telecommunications grids. For the military,infrastructure can be important during an operation to provide the logistics necessary for theoperations sustainment as well as to ease the transition to local authorities after a conflict(Patterson 2000:84, 86).Hills outlines four distinct features of urban operations. First, the physical terrain itself consistsof complex manmade structures that form an environment with several dimensions - bothvertical and horizontal as well as interior and exterior. The terrain itself poses tactical andstrategic challenges. Hazards unique to cities present further obstacles with inflammablematerials, gas leaks as well as increased ricochets and fragmentation from concrete buildingspresenting hazards not common to other operations. Hills further highlights the difficulties ofcommunication due to electronic interference and building density (Hills 2004:9). Second, urbanoperations highlight the limitations of current military operations that are designed for open areaswhere firepower and maneuverability is emphasized (Hills 2004:9-10, McGuiness 2000:3).Third, the presence of large numbers of non-combatants (Hills 2004:11). Large cities are dense,filled to the brim with people, and urbanization is an ongoing process (McGuiness 2000:1, Hills2004:16-17). Historical examples bear witness to higher civilian casualties as well as morebrutality in urban war (Hills 2004:11). The devastation seen in Stalingrad or Berlin during WW2is staggering when imagined in a city of tens of millions such as Tokyo, Seoul or New York. Thepresence of civilians furthermore affect the outcome of the conflict itself. Manifested in friendlynon-combatants that support a defending force with logistical help or as an early warning system(Gerwher & Glenn 2000:8-9). Lastly, Hills argues that urban operations limits technicaladvantages producing a far more brutal type of combat that most closely match that of preindustrial conflict (Hills 2004:12-13).[6]

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityMaster’s Thesis2017-05-24Toward a Theory on Urban WarfightingThe Nature of Urban WarAlice Hills argues that urban war is unique, and uniquely limiting for conventional forces. Sheargues that factors such as military necessity, pragmatism, frustration and fear give urban warwhat she calls a "pre-modern style of fighting" that is especially contrasting to Western norms(Hills 2004:142, 221). For Hills the pre-modern style is one of closer quarters and where air andartillery power is curtailed. She argues that "airpower and long-range bombardment must beaccompanied by a determined ground offensive" (Hills 2004:157). Within a city the boundariesbetween units are blurred and become "tactical weak points" (Hills 2004:153). The need for aground offensive combined with the close proximity of units in a city prompts Hills to refer tostreet fighting as "an aggressive, slow and dangerous business" (Hills 2004:143). Aggressiveclose combat is a core characteristic of urban war and the nature of the urban environment"obstructs maneuver and the application of firepower" (Hills 2004:57).Thus, warfare in urban environments is conceived of as something that is slow, hard-fought andfraught with casualties. The environment itself is especially obstructing, with buildings blockingcommunications and a three-dimensional landscape that favors the defender. Any tacticalmovement is dangerous and susceptible to ambush. Infantry combat is characterized by its closequarters nature with troops having to fight from house to house with difficult logistics and aunique proximity to the enemy. Hills highlights that the intensity of this type of combat isstressful and taxing on the soldiers performing it (Hills 2004:157, 220). Urban warfare then ischaracterized by its high attrition rates.The Presence of Non-combatantsHills highlights the presence of non-combatants as unique to urban operations. Cities havepopulations. Populations that invariably become part of any military operation within the city(Hills 2004:11). The urban environment is a human environment which is interactive (Hills2004:8) - a city and its population is an actor rather than a backdrop in a conflict. Thoughcivilians certainly are in danger of becoming victims of the fighting through collateral damagethey are sometimes directly targeted, not only through brutal acts, but in propaganda or[7]

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityMaster’s Thesis2017-05-24psychological operations (Hills 2004:230). This contrasts to the desire of Western forces to makewar cleaner - less costly both in collateral damage and casualties (Hills 2004:163). Hills arguesthat urban war and humanitarian war is irreconcilable - brutality and suffering is part of urbanwar (Hills 2004:245).According to Hills the characteristics outlined above are troublesome to reconcile with liberalnorms and its legal and moral framework (Hills 2004:220). The brutality of urban war, per Hills,means an acceptance of a certain degree of casualties and collateral damage. To pursue asuccessful military operation in an urban environment there is a need to engage in a type ofwarfighting that is often seen as a product of the past.The Promise of TechnologyHills argues that technological advancement and our understanding of the nature of war isintertwined (Hills 2004:64). While technology holds promise, these promises are yet unfulfilledand the nature of war in urban areas is unchanged from how it was conducted during the SecondWorld War (Hills 2004:64-65). Western forces avoid cities because cities counteract theirpreferred method of war - clean, precise and distant (Hills 2004:65). Sun Tzu wrote that "whenthe enemy concentrates, prepare against him; where he is strong, avoid him" (Tzu [Transl.Griffith] 1963:67). Hills argues much the same, highlighting the risk of enemies realizingWestern commanders desire to avoid urban combat and thus concentrating forces in cities so asto counteract the Western forces technological advantage (Hills 2004:65). Hills writes thattechnological advancement is not devoid of direction. Technological advancement is born of adecision to pursue technological solution to certain problems. In this, the understanding of theproblem, fundamentally the understanding of the nature of war, is important. Hills argues that inthe West operations in cities are understood as primarily a tactical challenge, thus technologyprovides tactical solutions. Technology becomes a support, an enabler that alleviates certaintactical obstacles. But it does not fundamentally change the nature of urban warfighting (Hills2004:71).The reliance of Western forces on airpower is another example of the idealized promise oftechnology. To politicians, airpower is precise, discriminating and cost-free (Hills 2004:71). It[8]

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityMaster’s Thesis2017-05-24lacks the bloodiness of an urban battle of attrition. Airpower holds significant limitations inurban warfare however. The urban environment provides diverse challenges such as flighthazards in the shape of high-density wires and antennas; light levels affecting night-optics onaircraft; the difficulty of urban personnel recovery; tactical issues in finding landing zones;rotary-wing aircrafts vulnerabilities in the confined spaces between high rises; effects of innercity air currents on helicopters; and electronic interference (Hills 2004:75). These challenges arecompounded with the danger presented by shoulder-fired anti-air missiles and high density smallarms fire (Hills 2004:75-76). Technology holds the possibility of a strong supporting role, butreliance on technology creates weakness when flaws in technology are realized. GPS-equipment,for example, provides an incredible information advantage but becomes utterly useless whenattempting to determine the location of enemy combatants several stories up in a high-rise (Hills2004:83).A Framework for Testing AssumptionsHills theory outlines several conclusions regarding what urban warfare is and what effect it hason the soldiers performing it. (1) Hills argues that in urban operations the warfightingcapabilities are crucial. She writes that "cities are volatile" and that a range of operations must beundertook for mission to be successful. As such, the skills of the combatants are more importantin these operations (Hills 2004:244). (2) Fighting in cities is "always difficult, destructive andmanpower intensive" (Hills 2004:244). (3) Urban war results in fighting in close proximitywhere the experience, training, motivation and cunning is more important than technologicaladvances or doctrinal innovations (Hills 2004:244-245).From this then one can glean some important assumptions that are testable against the historicalexamples available. Firstly, that urban combat entails some of the most difficult fighting. Theimportance of the skills of the soldier means that training for urban operations is important.Through training, the skills required for effective warfighting are gained. This is something thatHills herself highlights (Hills 2004:256-257). By examining historical accounts of mistakes andpoorly executed operations as well as well-executed operations it is possible to gauge if trainingwould have been or was beneficial.[9]

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityMaster’s Thesis2017-05-24Second, combat in urban terrain is destructive. This is no surprise. When the density of manmade structures increase, the destructiveness of operations should also increase. However, theassertion that urban combat is more difficult and more manpower intensive than other operationsis not as immediately clear. Other operations are certainly difficult and some have high demandsin manpower. By examining cases this assumption is testable. Difficult operations should takelonger, have more casualties and generally require a harder fight. If an operation is manpowerintensive, we can assume that the enemy either has numerical superiority which must be rectifiedor a force multiplier that require additional soldiers for the success of an operation. A city can beseen as this type of force multiplier.Third, while fighting in close combat puts a premium on training and experience it is oftentechnological advancement that is thought to be most promising (Hills 2004:254). Urbanoperations seem to level this playing field in two general ways. First by limiting the scope oftechnology through electronic interference on comms, obstacles for aircraft or obfuscating GPStracking. Second by making older technology viable through adaptation. For example, the use ofRPGs to bring down Black Hawk helicopters in Somalia during the international intervention(Hills 2004:77). Examining this requires examining the type of threat highlighted as mostdangerous in an operation. If advanced anti-air with night-optics used to bring down enemyaircraft is the most dangerous we can assume that technology has played an important role. If,however, the most dangerous threat is RPGs and high-intensity small-arms fire then technologyis being equalized rather than providing the type of advantage Western forces seek.Testing these assumptions is important in testing Hills theory. If the maneuver warfare focusedon tempo and aggression is an ill-fit for the slow, dense urban environment then the aboveassumptions should hold true. Examining historical cases we should thus see a consistent patternof slow, attritional warfare where numerical superiority is equalized by entrenched defenders andtechnological advantages are counteracted by older technology adapted to work in an urbanenvironment.[10]

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityMaster’s Thesis2017-05-24MethodologyStructured, Focused ComparisonIn order to test the theoretical framework derived from the theories of Alice Hills this paper willconduct a comparative case study using the method of structured focused comparison. AlexanderGeorge and Andrew Bennet explains that a structured focused comparison is one where theresearcher uses a structured method, asking generalized questions, with a focus on certainaspects of a historical case in comparison with similar cases (George & Bennet 2005:67). Theselection of cases should reflect the research objective as well as clearly define the universe ofcases from which selection is made. It is important to understand what phenomenon the case isan example of. This is derived by clarifying the research objective which highlights the aspectsthe research intends to focus on. The generalized questions must also reflect the researchobjective as well as the theoretical focus of the paper. The questions strive to provide an abilityto collect generalizable data from similar, but diverse, cases which will allow comparativeresearch to be undertaken (George & Bennet 2005:69).George and Bennet argue that the most important part of a good research design is formulating aresearch objective. This is closely connected with identifying a research problem (George &Bennet 2005:74). Together, these two aspects inform the rest of the research design. A theorytesting research objective is aimed at testing the validity and scope conditions of one or moretheories (Bennet & George 2005:75). Stephen van Evera writes that there are two general waysof testing theories, through experimentation and observation. Observational tests furthermoregenerally come in two forms, large N-studies and case studies (Van Evera 1997:27). Anobservational theory test then is when an "investigator infers predictions from a theory" that arethen tested by observing data and deferring whether the prediction unfolds as expected (VanEvera 1997:28). Ian Shapiro highlights some of the difficulty in establishing a research problem.He argues that a theory-driven approach lends itself to pitfalls and a desire to vindicate theory inthe face of observation (Shapiro 2002:599-601). Shapiro argues for a problem-driven approachwhere the puzzle of the phenomenon observed is object of study. The researcher then studiesprior theoretical work to establish whether these sufficiently explain the puzzle observed(Shapiro 2002:603).[11]

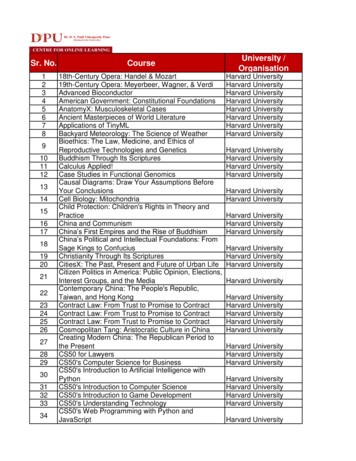

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityMaster’s Thesis2017-05-24At face value this might contradict the essentially theory-driven objective of theory testing.However, theory is the explanation of a causal law of why a phenomenon occurs. The law itselfrelates to the relationship between variables – in essence, how a phenomenon occurs – while atheory explains the relationship between the variables, the why of how a phenomenon occurs(Van Evera 1997:8-9, Walz 1979:1,3) As such, good theory is ideally problem-driven. It aims toilluminate both how a puzzling phenomenon works and why this relationship functions. Testingan established theory, then, is fundamentally problem-driven. The puzzle at the core of this paperis why urban warfare is so destructive and difficult, examined by testing whether the establishedtheory of Alice Hills can adequately account for this puzzle.George and Bennet highlight the need for clear variables in this type of research design (George& Bennet 2005:79). Two types of variables are commonly used in social science research. First,the dependent variable which can be thought of as that which is studied. The dependent variableis the phenomenon which the researcher aims to explain (Van Evera 1997:11). Second, theindependent variable is that with which we explain the studied phenomenon. That is, theindependent variable is what the researcher posits will account for variations in the dependentvariable (Van Evera 1997:10). This paper will make use of two dependent variables that reflectthe theoretical framework previously presented. The first dependent variable is the pre-modernnature of combat that distinguishes urban warfare. This pre-modern type of combat can beexplained by two variables, (1) the defender’s ability to entrench in the urban environment and(2) the close proximity most fighting takes place in. These two independent variables coalesce tocreate a type of combat that is at odds with the preferred modern type of combat. The seconddependent variable is the negation of technological advantages that occur in urban combat. Twovariables affect this, (1) the environmental limitations urban environments place on moderntechnology and (2) the ability of defenders to adapt older technology for use in urban combat.These two variables create an environment that equalizes the disparity in levels of technology.The relationship between variables by the Table 1 below.[12]

Viktor VillnerSwedish Defense UniversityDependent VariableMaster’s Thesis2017-05-24Independent VariableDV 1 – Pre-modern nature of combatIV1 – Defenders ability to entrenchIV2 – Proximity of fightingDV2 – Negation of technological advantageIV3 – Environmental limitations on technologyIV4 – Older technology adapted to urban combatTable 1: Relationship of variablesGeorge and Bennet posits that the relevance of a case to the research objective is the mostimportant factor in case selection (George & Bennet 2005:83) When selecting cases George andBennet also argues that these "should [.] be selected to provide the kind of control and variationrequired by the research problem" (George & Bennet 2005:83). Some problems require similarcases while others require cases with variation. The classification of the universe of cases inconjunction with the

his book Mars Unmasked (2009) . disseminated in the U.S. military among non-specialized infantry units in his 2016 article “Close Quarters Battle: Urban Combat and ‘Special Forcification’”. . close combat is a core characteristic of urban war and the nature of the urban e