Transcription

PERSPECTIVESon Eminent Domain Abuse5VolumePerspectives on EminentDomain Abuse is a seriesof independently authoredreports published by theInstitute for Justice

1The Truth About Times Square,

2THEABOUTTRUTHTIMES SQUAREBy popular lore, the revival of Times Square ranksamong the most celebrated achievements of NewYork City in recent years. In the 1960s, 1970s andearly 1980s, Times Square was sleazy, crime-ridden andso physically and economically blighted it represented athreat to public safety—but today it is nearly crime free.It is filled with tourists, and world-class corporationsdwell and prosper within its borders. It is celebratedas a triumph of “urban planning,” “public-privatepartnership,” the wise use of the power of eminentdomain, an example of the intelligent intervention ofgovernment into private real estate markets.All of it is a myth.In 1983, when I went to work for GovernorMario Cuomo as chairman and chief executive of NewYork State’s Urban Development Corporation (UDC),I was convinced I knew how government planningcould transform the Times Square I saw at that time towhat it is today. The truth is, however, almost none ofthe grandiose plans my colleagues and I created andaggressively spearheaded ever came to fruition. Ourextravagant plans actually retarded development. Thechanges in Times Square occurred despite government,not because of it. Times Square succeeded for reasonsthat had little to do with our building and condemnationschemes and everything to do with government policythat allowed the market to do its work, the waydevelopment occurs every day nationwide. By loweringtaxes, enforcing the law, and getting out of the wayinstead of serving as real estate broker, the governmentincentivized investment and construction and encouragedthe rebirth of Times Square to what it is today.I would not realize that until later, of course, forin the early 1980s, I headed one of the most influentialgovernment redevelopment agencies in the state ofNew York. Governor Nelson Rockefeller created theUDC in the 1960s to build low-income housing.1 Bystatute, it had been given powers that, at the time, wereunprecedented for a governmental development agency.It could override local zoning, issue bonds, serve as itsown building permit agency, supervise constructionand, most importantly, condemn property for reasons

3The Truth About Times Squareof “economic blight,” a term the UDC used for areasit felt were underperforming economically. Seeingits enormous power, Governor Carey’s administrationtransformed the agency from its original purpose ofbuilding low-income housing (a purpose that the agencyhad used to drive the state and city into a very seriousfiscal crisis in the 1970s2) to a full-blown economicdevelopment agency that co-opted the functions ofthe private market, engaging in real estate speculationand procurement (instead of focusing on creating aninviting environment for private development withoutgovernment assistance or subsidy). For that reason, theUDC played a central role in planning the redevelopmentof Times Square, which had reached its absolute nadir in1981.Already by 1960, the heart of Times Square—42ndStreet between Seventh and Eighth Avenue—wasfrequently asserted as “the ‘worst’ [block] in town,” aspointed out by The New York Times.4 The article’s authorTIMESSQUARETHE NOT-SO-GREAT WHITE WAYIt is important to recall accurately what TimesSquare was like in the early 1980s. Although revisionistsargue that it was an area full of harmless, playfulestablishments, Times Square was anything but. 3 Thearea began to decay during the late 1950s after the sexindustry pushed out the once-lustrous theaters that hadbeen struggling economically since the Great Depressionof the 1930s. The decline was rapid and hastenedby the police’s abandonment of the area. The newestablishments could have been limited or controlledthrough zoning, but the city was unable to do so dueto the rulings of judges in the 1960s and 1970s thatlegalized sex shops. Compounded by Times Square’saccessibility and central location—the Port Authority busterminal at 42nd Street and 8th Avenue and the subwaystation, which was the center of the entire city’s subwaysystem, made the area a heavily trafficked transportationhub—and little enforcement of the law, it is no wonderthat a strong criminal element accompanied the thrivingadult industry that took root.found that the paradox of 42nd Street was that “placesthat attract deviants and persons looking for trouble areinterspersed with places of high standards of food, drinkand service. Some of them will not serve an un-escortedwoman.”5 The 1969 hit movie Midnight Cowboyaccurately depicted the Times Square of that decade:gritty, dark and desperate, a zone distinctly apart from itsmore productive and habitable neighbors.The situation worsened in the 1970s, and by the1980s, things were worse still, with an amazing 2,300crimes on the block in 1984 alone, 20 percent of themserious felonies such as murder and rape.6 Dispiritedpolice—at the time more concerned with avoidingscandals than fighting crime, especially low-levelcrime—would investigate the serious felonies but stood

4by and watched as disorder grew. William Bratton,appointed New York City Police Commissioner in 1994,recognized this trend: “The [NYPD] didn’t want highperformance; it wanted to stay out of trouble, to avoidcorruption scandals and conflicts in the community. Foryears, therefore, the key to career success in the NYPD,as in many bureaucratic leviathans, was to shun risk andavoid failure. Accordingly, cops became more cautiousas they rose in rank, right up to the highest levels.”7 Thecity government had no idea that tolerating low-levelcrime created an environment that inevitably led toserious law-breaking. There was no “broken windows”theory8 in play.Naturally, high levels and fear of crime deterinvestment and growth, and the lawless climate haddevastating economic consequences for the city. In1984, the entire 13-acre area identified in our eventualredevelopment plan employed only 3,000 people in legalbusinesses and paid the city only 6 million in propertytaxes9—less than what a medium-size office building inManhattan typically produced in tax revenue. As headof the UDC during the mid-1980s, I walked through thearea at night and felt nervous revulsion. We wouldhurry past prostitute-filled, single room occupancy hotelsand massage parlors, pornographic bookstores, X-ratedmovie houses and peep shows, all accompanied by anassortment of junkies and pushers and hoodlums andjohns and hookers and pimps—the whole panorama ofbig-city low life.What made it worse was that in the early 1950s,Times Square had been a childhood delight for me.On Saturdays, my father and I would bus down fromHarlem to see a movie, often a Roy Rogers or GeneAutry cowboy picture. Then we’d eat at Nedick’s andafterward just stroll around, gazing up at the giantsigns that adorned Times Square buildings. My fatherremembered first hand the Times Square heyday of the1920s when 13 theaters studded 42nd Street betweenEARLY YEARStheof TIMESSQUAREIn the 1890s, theaters flourished in Longacre Square,largely lured to the area by Oscar Hammerstein’s newOlympia Theater; by 1925, there were approximately80 theaters. Because the city had not yet installed streetlighting in this burgeoning district, the fronts of the newtheaters became giant advertisements for their plays andactors. This was followed by similar signs for products,ultimately lighting up Broadway and earning LongacreSquare the nickname, “The Great White Way.”In 1904, Longacre Square was renamed “TimesSquare,” after The New York Times moved itsheadquarters to the neighborhood on 42nd Street.Nine years later, the media giant moved to a differentbuilding, but the area maintained its name and iconicstatus. As subway and bus stations opened en masse,Times Square became a heavily trafficked transportationhub, finding itself at the “Crossroads of the World.”Times Square represented the archetypal American city:culture, bright lights, and bustling streets.Following the Great Depression and World War II,Times Square slid towards the same fate as many otherpopular inner-city districts. As families preferred thesafe suburbs to the chaotic, unpredictable city streetsand stayed home to watch television instead of spendingan evening at the theater, Times Square began cateringto a new customer that didn’t retreat. Theaters beganshowing pornography, drugs were dealt on the streets,and adult stores flourished.“Times Square,” St. James Encyclopedia of Popular Cultures,St. James Press, 2000. Reproduced in History Resource Center,Farmington Hills, MI: Gale.Times Square in 1908.

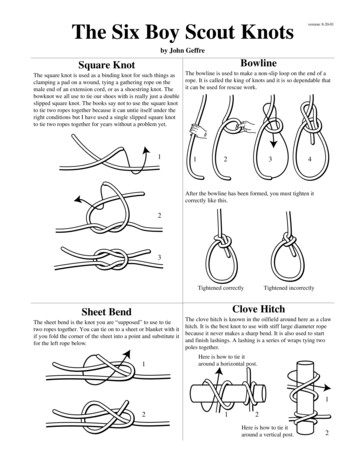

5The Truth About Times Square Brown Brothers, Sterling, PAAbove: Times Square in 1919. Right: Johnson and Burgee’scontroversial design for the four towers.Seventh and Eighth Avenues and lit up in neon “TheGreat White Way.” Theatergoers crowded into the latestcreations of impresario George M. Cohan or musicianssuch as George and Ira Gershwin.Many involved with the redevelopment plan heldsimilar memories, and the regret we felt over the passingof this glamorous world gave the project a powerfulemotional boost. Our conclusion was unanimous andunequivocal: Something had to be done.THE 42ND STREET DEVELOPMENT PLANUnder my watch, the UDC gained approval toput in place one of the largest urban renewal projectsnationwide, in the heart of midtown Manhattan noless. Mayor Koch—who assumed office on the tail Thorney Liebermanof a traumatic fiscal crisis—and Governor Cuomoenthusiastically supported it. Although fierce, bitterrivals, both “saw political opportunity in the raggedmorality of the notorious boulevard. Each sensed thechance to create a higher national profile for himselfas the moral savior of ‘the Deuce.’”10 And so thetumultuous collaboration began.The 42nd Street Development Project would havemade the emperors of Rome green with envy. Its biggestcomponent was to be Times Square Center: four giantoffice towers, containing 4.1 million square feet of floorspace in all, looming over Times Square’s southernborder. Offered a 240 million tax abatement, relativelyunknown George Klein’s Park Tower Realty woulddevelop the site. Upon being chosen, Klein had justcompleted only his third major building in New York City,raising many eyebrows as to why this newcomer wouldget this potentially (and enormously!) lucrative nod.

6Perennial modernist Philip Johnson, togetherwith fellow architect John Burgee, would design thebuildings. In Johnson’s controversial design, four-storyred granite bases would support glass towers toppedwith iron crested glass mansard roofs. Each towerwould light up at night to dispel the shadow worldbelow; at street level, a pedestrian thoroughfare wouldconnect the four towers and establish a new hub forsubway travel.Johnson’s gargantuan buildings were not theonly part of the redevelopment project conceived on agrand scale. We also called for a 2.4-million-squarefoot computer and garment wholesale mart between40th and 42nd Streets on the east side of Eighth Avenueand a 550-room luxury hotel with additional office andretail space on West 42nd Street at Eighth Avenue. Ninehistoric theaters, including the legendary New Victoryand the New Amsterdam, would receive a 9 millionspruce up and reopen as nonprofit cultural centers. Thefinal component was a major 100 million makeover ofthe 42nd Street subway station, which would be outfittedwith a computerized information center, scores of shopsand six new entrances, among other improvements. Aspart of the overall deal, Park Tower Realty would pickup most of the tab for the nonprofit theaters and thesubway.11which reduced development opportunities on the EastSide and loosened zoning restrictions on the West Sidebetween 6th and 8th Avenues and 40th and 60th Streetsfor six years.12 The rezoning was originally conceived byMayor Lindsay, who thought that the century-old zoningregulations kept Times Square in an undeveloped blackhole that sank further and further towards economicdecline in the 1960s. When the promise of upzoningbegan to take shape, property owners—with theanticipation of being bought out by mega-developersin the immediate future—began renting on short termbases to those more than willing to work in the lewdenvironment: sex shops.13The first goal—restoring “The Great WhiteWay” to its previous glory—relied on the wholesalecondemnation of the 13-acre target area. We felt thateverything had to go forward at the same time, since thesheer momentum of the development would change thearea for good.ONWARD!Unveiling the plan early in 1984, we felt enormouspride. After all, how many people have the opportunityPAVING WITH GOOD INTENTIONSWe wanted to remove the barriers in TimesSquare that seemed to keep private investment atarm’s length, while also shifting development from thecongested East Side of Manhattan to the West Side.What we didn’t realize at the time, of course, was thatour efforts would push that investment even farther outof reach.The city passed the Midtown Zoning Resolutionin 1982 to encourage the goal of shifting development, New York Times GraphicsThe 42nd Street Development Project plan as conceived in 1983. Thetrade mart would take up 2.4 million square feet.

7The Truth About Times Squareto leave such a deep and positive mark on the historyand landscape of a premier world city? I did wonder atthe time, could we really pull this off? After all we werenot Caesar, but just a group of New York City kids. But Isuppressed my doubt.By this time, I had also grown revolted withNew York’s pervasive political corruption. New Yorkgovernment is a perennial scandal, but the climate ofthe 1970s and 1980s seemed particularly crooked withnumerous prominent public officials being indicted andevidence of many others on the take. The situation grewbad enough to draw national attention in the famousbook City for Sale14 and propel Rudolph Giuliani tofame as the crime-busting U.S. Attorney in New York.Disgusted by the perfidy of supposed “public servants,”I informed Governor Cuomo that I would soon step downas head of the UDC. I left public service in 1985 withplans to never return to New York politics or government,plans I have since stood by. But before I left, I wantedto feel as if I had accomplished something worthwhile ingovernment. This project would be it.Because the UDC was the lead state agencyfor this project, I represented one of the key playersin implementing the redevelopment of Times Square.Working closely with Governor Cuomo, the UDC boardand representatives from the city, I approved or opposeddevelopers for the project, directed the various UDCdepartments and subsidiaries involved in the work (suchas the legal and engineering divisions) and approved allproperty condemnations contained in the plan. The lattermade my agency a particularly powerful player, sincethe city had to rely on the UDC’s exclusive condemnationauthority. Indeed, this role was one of the key reasonsthe city wanted to make this a joint effort with the state—we could fast-track the development process andcondemnations and offer tax abatements. This city-statepartnership was a unique alliance that other large-scaledevelopment projects throughout the country did not have.

8On November 8, 1984, the now-defunct NewYork City Board of Estimate—a body composed ofcity-elected officials that approved land use projects—approved the 42nd Street Development Project, removingthe last political hurdle to its implementation. TheUDC did not technically need city approval, but a 1982agreement established that the redevelopment wouldbe a joint city-state effort.We all exhaled in relief, since reaching that pointhadn’t been easy.From the moment state and city officials firstannounced the redevelopment scheme in 1981, it facedopposition from activists, who worried that it woulddisplace lower-income people from their homes in theneighboring Clinton area of Manhattan by causing rentsto rise. Meanwhile, those on the cultural left, whohad always defended Times Square’s sex businessesas protected speech, attacked the project for its planto kick these businesses out. They believed the realmotive of removing this activity was driven by moralbeliefs; as a party to the planning, however, I canattest that the true desire was to protect the area’seconomic potential from the deleterious effects of thelawless environment. My colleagues and I promotedthis project as the only solution; we were sure thatmassive government intervention was the only way tosave Times Square, and the only way to start was witha fresh slate: wholesale condemnation.An internal disagreement broke out in 1983 overwho would receive the potentially lucrative nod todevelop the 2.4-million-square-foot wholesale mart. Thecity and The New York Times favored a team of TrammelCrow (a Texas-based developer) and George Klein, thedeveloper chosen to build Times Square Center. Thestate, wanting more diversity in the project, believedGeorge Klein had enough on his plate with Times SquareCenter’s four giant office towers. We preferred PaulMilstein, an experienced and major New York developer.Milstein had, in fact, developed a hotel just north of thethe NEW YORK TIMES& EMINENT DOMAIN ABUSEIn 2001, The New York Times was able to useits connections once again to influence the state tocondemn an entire city block in Times Square for itsthird and latest headquarters move, just three blocksfrom its second home.The Wallace family had owned the property at 620Eighth Avenue since the turn of the 20th Century, andhad recently spent more than 3 million refurbishingthe six-story building, attracting two major tenantsin the late 1990s—a feat that proved out of reach forthe UDC and city government in previous years. TheOrbachs owned a 16-story building at 265 West 40thStreet with 30 tenants, and the neighboring SussexHouse dormitory housed 140 students.Ten properties and a parking lot—all of which hadbeen struggling to survive and thrive under the threatof eminent domain for the merchandise mart since1981—were razed for the family newspaper’s newhome.David W. Dunlap, “Blight to some is home to others; concern overdisplacement by a New Times building,” New York Times, Oct. 25,2001, at D1.project area. He saw the Square’s potential, and hishotel was actually the beginning of its revival a decadelater.T H E NE W Y O R K T IME S’WHOLESALE INFLUENCE PEDDLINGIt was then that I began to see the negativeimplications of government-directed projects likethis—the influence peddling, cronyism and corruption,especially when eminent domain is involved. Usingeminent domain for private development gives the

9The Truth About Times Squareprivate sector the opportunity to wield public power—which is more or less for sale—in order to benefitprivately. One of the more prominent yet untold playerswas The New York Times, a private company that wasdeeply involved in this public project. As the newspaperof record in New York, they would naturally cover theproject closely—but their involvement transcendedjournalistic scrutiny.For example, Jack Rosenthal, then deputy editorialpage editor of the paper, was the Times’ point man inrepresenting their interests about the redevelopment.He acted not as a journalist covering a story but as adecision maker, dictating public policy. Rosenthal wasspeaking for the paper, and the paper was part of theNew York Times Corporation. The Times Corp. haddecided it should have as much decision power as city orstate government with regard to 42nd Street.They did so in many ways. One of theprimary methods was to use their close relationshipwith important city officials, such as city planningcommissioner Herb Sturz (the city’s point man on theproject and my equivalent for the city), who later wentto work for the Times after he left city government. Anincident that demonstrates Sturz’s relationship with theTimes occurred at a city-state meeting to discuss theproject. At the meeting, Sturz announced, “Punch [ArthurSulzberger, former publisher of the Times] wants 1Times Square down.” At other times it was unvarnishedattempts at pressure. In a private meeting, Rosenthalmade it very clear to me that the Times wanted Kleinto develop the garment wholesale mart and grewincreasingly upset at my opposition to the idea.What surprised me most was that nobody at theTimes seemed to care that they were compromisingtheir journalistic integrity by assuming the dual rolesof political reporting and pure politicking when it cameto 42nd Street. Yes, the Square was named after thepaper and the Times was the largest property owner inthe project area, so it is understandable they were veryinterested in the government’s decisions. Yet beinginterested and covering the story closely is differentthan assuming a decision-making role and assigning aneditorial page executive to tell government officials whatto do.After the city threatened to pull out of thejoint project, we settled on a new team to head thedevelopment: Trammel Crow would operate the 400million trade mart, Tishman Speyer Properties wouldbuild it, and Equitable would provide much of thefinancing.It was agreed that Sturz and I would meet on aregular basis to avoid future misunderstandings likethe one that arose around the choice of developers.This temporary détente did not, however, preventthe powerfully connected from asserting control overtheir particular spheres of interest. One episode soon New York Times Graphics.According to the New York Times, nearly a dozen projects wereunderway in 1986 north of the 42 nd Street Development Project area.

10after our agreement illustrated this quite clearly: Wetook turns hosting the meetings, and on one occasionSturz hosted the meeting not in a city office, but in aconference room of the Times’ headquarters. It wascompletely inappropriate to hold such a meeting in aconference room of one of the redevelopment area’smost prominent private property owners, but it gaveSturz and the city the opportunity to play politics andsend a message to the state and me that they were tightwith the Times—a message we clearly received.Although a well-known and influential newspaper,the Times is, at its core, a family business. Why shouldthis corporation have the power to decide who willown and lose property on 42nd Street? In fact, why wasthe government picking developers in the first place?Mega-developers Paul Milstein (the UDC’s preferreddeveloper) and Douglas Durst also owned property in thearea and wanted to develop Times Square. These weremen confident of their ability to develop without thegovernment’s help or interference. They expressed to metheir resentment at the Times’ involvement.But this wasn’t the only example of questionabledealings by players involved in the redevelopmentproject. At that time, a tiny New York law firm,Blutrich, Falcone & Miller, was retained by many megadevelopers. A firm of its size would not ordinarily haveenjoyed such lucrative business, except that the firmwas closely connected to Governor Cuomo and his sonAndrew (now New York State attorney general). Thelaw firm had among its partners a former assistantto Governor Cuomo from Cuomo’s days as lieutenantgovernor, and another former assistant who worked forGovernor Cuomo when he was in private law practice.Andrew joined the law firm as a partner. The Times,which ran an exposé on all of this,15 showed that theCuomos had, in fact, embraced the “me and my friends”culture of Albany state government. I do not know ifthe Times exposed the Cuomo law firm as part of theirjournalistic activities or if they were sending a messageto the governor that there could be only one majorpower broker on 42nd Street—The New York Times.Unsurprisingly, the Times never ran a story on their owninvolvement with the Times Square project.THE GRAND SCHEME WITHERSDespite all of the posturing and scheming,planning and skullduggery, the plan withered. Kleinnever started work on the four office towers, which neverwent up; the garment wholesale mart never opened,the hotel never appeared, the subway renovations neverhappened and the nonprofit theaters never materialized.In 1986, the city and state cancelled an agreementit had with developer Michael Lazar—who was the city’stransportation administrator in the 1970s—to renovatefour of Times Square’s theaters, citing corruptionallegations.16 Lazar was also found to own the CandlerBuilding, which he bought right before being hand-pickedby Koch to renovate the theaters. The Candler Buildingwas one of two properties conspicuously left off of theproperty acquisition list.In August, the Dewey Ballantine law firm, whichwas to have been a major tenant in Times Square Center,withdrew because it couldn’t wait six years for theoffice space it needed. In 1989, the number of lawsuitsbrought against the project reached 40 and ChemicalBank (now part of Chase), another anchor tenant,dropped out. That same year, Johnson and Burgeeredesigned the massive office towers in an attemptto assuage New Yorkers’ fears that Times Squarewas being changed forever, but to no avail. In 1991,George Klein and his new partner, Prudential Insurance(Equitable had dropped out), formally sought a delay intheir development obligations, but officials continuedunfettered in their efforts to condemn the properties inthe 42nd Street Development Project area.By 1992, Governor Cuomo was letting thedevelopers off the hook. “It doesn’t make sense to go

11The Truth About Times Squareforward immediately with the building of the officetowers—there’s no market for them,”17 the governorobserved, acknowledging that, in the end, it was themarket and not a government development plan thatwould decide the fate of Times Square. “To holdthese people to the contract is to ask them to commitan act of economic self-mutilation,” the governoradded for emphasis. Six years earlier, Douglas Durstmade this same observation. The Durst Organizationowned parcels in the block bounded by 42nd and 43rdStreets and Broadway and 6th Avenue, but in 1986,Durst asserted that there were no immediate plansfor development “because we don’t think that thedemand for new office space will support the cost of itsconstruction.”18 In August, the 42nd Street DevelopmentProject collapsed. The construction of the four officetowers was officially put off indefinitely. It was clear toDurst “a long time ago that the office towers would notbe built.”19The following year, an “interim” plan wascreated to include two new low-rise structures,the refurbishing of 11 existing businesses, and theconstruction of new lighting and signage. Shiftingaway from the focus on office development, of whichthere was a severe oversupply in New York City, mysuccessors focused on what the public—and themarket—demanded: to recreate the Times Square thatwas so beloved during its heyday.Later, after more than a decade on the project,George Klein, the developer anointed by The New YorkTimes, left, having built or renovated nothing. It seemsThe New York Times was no more adept at choosingdevelopers than were elected officials.MEANWHILE While the original building project firstconceived in the early 1980s stalled, somethingsurprising happened: Times Square started to revive.CITY-STATE ALLIANCEas a PROTOTYPE forBIG DEVELOPMENTUnfortunately, the most atrocious aspects of theTimes Square redevelopment have been embraced as agrand tradition in New York City development, as theunique city-state alliance forged through our efforts inthe 1980s paved the way for future massive interventionat both levels of government. Influence peddlingis still as prevalent as ever, as billionaire developerBruce Ratner’s buddies in office have helped him seizeprivate homes and businesses for his Atlantic Yardsproject in Brooklyn—despite massive public outrage.Columbia—a wealthy, private university—isusing its influence to wipe out an entire West Harlemneighborhood to expand its campus, even makinga secret agreement to cover costs of condemnationand acquisition with the Empire State DevelopmentCorporation (formerly the UDC).In Willets Point, Mayor Bloomberg is threateningto seize hundreds of tax-paying, thriving businessesthat the government has long neglected—for decadesdenying them such basic services as garbage collection,plumbing and electricity—for a half-baked, pie-in-thesky development plan, using the blight the city itselfcreated as justification. Clearly, both the state and citygovernments did not learn from the dismal failure ofthe Times Square redevelopment, continuing to makethe same mistakes over again at the expense of propertyowners and those living and working in the targetedareas.Indeed, every large-scale project making the frontpages of New York papers today involves the use ofeminent domain for politically connected developers’gain.Theresa Agovino, “Atlantic Yards still just an artist’s rendering;Project stalls amid lawsuits, recession and credit crunch,”Crain’s New York Business, Jan. 19, 2009, at 3; Robert Kolker,“Because sometimes immense, gratuitous, noncontextual actsof real-estate ego don’t pan out,” New York Magazine, Dec. 22,2008; Erin Durkin, “Columbia U. letter on expansion incitesprotest,” Columbia Daily Spectator, April 21, 2005; FrankLombardi and John Lauinger, “Willets Point project now adone deal,” Daily News (New York), Nov. 14, 2008, at 4.

12First it was a trickle of activity. In 1989, Viacom, thehuge entertainment firm that owned Nickelodeon andMTV, signed a lease at 1515 Broadway.20 In 1992, theGerman publishing giant Bertelsmann AG bought 1540Broadway from Citicorp.21 Even recent setbacks werereversed, as when Morgan Stanley decided to “golong” on Times Square and purchased 1585 Broadway,the former Solomon Equities building that had beenlargely empty since a 1991 bankruptcy.22 Then thetrickle became a flood. As the Dinkins administrationtransitioned to the Giuliani administration, the WaltDisney Company an

York City in recent years. In the 1960s, 1970s and early 1980s, Times Square was sleazy, crime-ridden and so physically and economically blighted it represented a threat to public safety—but today it is nearly crime free. It is fi lled with tourists, and world-class corporatio

![BCA160 Macrame [2015] - NDSU](/img/19/bca160.jpg)