Transcription

NIHMedlinePlusTrusted HealthInformation from theNational Institutesof HealthFALL 2019MAGAZINEIN THIS ISSUEA Couple’s Journey withLewy Body DementiaUpdates on Sleep ApneaSpeaking Up AboutStutteringUnderstandingStandard Lab Tests8 HealthQuestions toAsk Your FamilyMembersCOVER STORYBasketball star Kevin Love on anxiety and removing stigma aroundMEN’S MENTAL HEALTH

In this issueDWHO WE AREThe National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the nation’spremier medical research agency, with 27 differentinstitutes and centers. The National Library of Medicine(NLM) at NIH is a leader in research in biomedicalinformatics and data science research and the world’slargest medical library.NLM provides free, trusted health information toyou at medlineplus.gov and in this magazine. Visit us atmagazine.medlineplus.govThanks for reading!CONTACT 000CONNECT WITH USFollow us on /Follow us on Twitter@NLM NewsNIH MedlinePlus magazine is published bythe National Library of Medicine (NLM) inconjunction with the Friends of the NLM.Articles in this publication are written by professionaljournalists. All scientific and medical informationis reviewed for accuracy by representatives of theNational Institutes of Health. However, personaldecisions regarding health, finance, exercise, and othermatters should be made only after consultation withthe reader’s physician or professional advisor. Opinionsexpressed herein are not necessarily those of theNational Library of Medicine.IMAG ES: COVER, D EREK KET TEL A; TOP, COU RTESY OF THE NBPAid you know that more than31% of U.S. adults experience ananxiety disorder at some pointin their lives, according to the NationalInstitute of Mental Health (NIMH)?For our fall issue cover feature,Cleveland Cavaliers basketball playerKevin Love opens up about his ownstruggles with anxiety and his path tomanaging the condition. He talks aboutthe special challenges facing men withmental health conditions and explainswhat he’s doing to combat that stigma asan athlete and advocate.We also spoke with the NationalWilliam Parham, Ph.D. (center) is the first-ever director of the NationalBasketball Players Association’s MentalBasketball Players Association’s Mental Health Program. Also picturedHealth Program Director William Parham,are Antonio Davis, Keyon Dooling, Michele Roberts, Garrett Temple,Ph.D., about their new program to helpand Chris Paul.players stay healthy both on and off thecourt and with leading researchers fromNIMH to get the latest, need-to-knowFinally, as you gather with loved ones thisinformation on anxiety conditions.season, make sure to take a look at our helpfulAlso in this issue, we provide research updateslist of health questions to ask your family.from around the National Institutes of Health onDiscussing medical conditions or diseasesconditions including stuttering, sleep apnea, andmay help determine if you have a high risk.Lewy body dementia, a serious but lesser knownWe hope you enjoy our fall issue and wishdisease that is the second most common formyou a happy and healthy holiday season.of dementia.

Trusted HealthInformation from theNational Institutesof Healthinside12Basketball player Kevin Loveexplains how he managesanxiety and depression.F E AT U R E SD E PA RT M E N T S08 Speaking up about stuttering04 To your health12 Reaching great heights28 From the labLatest updates from NIHI MAG ES: TOP, D EREK KET TEL A; RI GHT, ISTOCKHow NBA star Kevin Love isnormalizing the conversationaround men's mental health18 Lewy body dementiaWhat you need to know24 Wake-up callHow sleep impacts our mindsand bodiesFALL 2019Volume 14Number 3News, notes, & tips from NIHLatest research updates from NIH30 On the webFind it all in one place!31 Contact usNIH is here to helpCommon antidepressantsand how they work6

toyourhealthNEWS,NOTES,& TIPSFROM NIHThe 411 on standard lab testsLearn why they are ordered and what common terms meanHEALTH TIPS October marks Health Literacy Month,which focuses on better understanding and managingour individual health.In recognition of Health Literacy Month, we’veput together an overview of common lab tests withinformation from MedlinePlus and NIH.When you see your health care provider, they may ordera lab test. This test could be a small sample of your blood,urine, body fluids, or body tissues (like cells) to see if youhave any health conditions or diseases.In general, health care providers perform blood or urinelab tests to either help find out if you do or do not havea certain condition or disease—often before anysymptoms appear.Make sure to inform your provider and lab technicianabout medications you take and if you feel sick that day.Some tests, such as a blood glucose test, may requireyou to fast for 12 hours before the test to get moreaccurate results.Common lab tests include:ɠ Complete blood count: Checks your overall health andis often given during the yearly checkup. Testing yourred and white blood cell count can show if you have aninfection (high white blood cell count) or anemia (lowred blood cell count).ɠ Blood cholesterol test: Measures cholesterol levels.Cholesterol is a wax-like substance found in our bodies.In high amounts, it can clog arteries and lead to healthissues. This test can help you better understand your riskfor heart disease, stroke, and other problems caused bynarrowed or blocked arteries.4Fall 2019 NIH MedlinePlusɠ Blood glucose test: Measures the amount of sugar inyour blood. It can monitor or detect diabetes, a conditionin which your blood sugar levels may be too high.ɠ TSH test: Measures the amount of thyroid stimulatinghormone (TSH) in your blood. TSH is produced by thepituitary gland, which releases hormones into yourblood. Along with other tests, it can help detect thyroidproblems like hypothyroidism (underactive thyroid) orhyperthyroidism (overactive thyroid).ɠ Pap test (or Pap smear): Detects or prevents cervicalcancer by analyzing a small sample of cells from awoman’s cervix. The test may happen at a checkup witha primary care provider or with a gynecologist, a doctorwho focuses on reproductive health.IMAG E: ADOBE STOCKWhat is a lab test?

Understanding ALSMost cases occur randomly without anyrisk factorsMaking sense of it allYou received your lab results. Now what?Your health care provider shouldcontact you to confirm your results looknormal or to let you know if any testsrequire follow-up. They are trained tointerpret data and results from thesetests. If you don’t hear back from yourmedical office, make sure to follow up.Here are a few common terms youmight see:ɠ Normal or negative: This meansnothing has changed, and there are noconcerning substances found in yourblood or urine test.ɠ Abnormal or positive: This meansthat the provider found something inyour blood or urine that needs furtheranalysis.ɠ Inconclusive or uncertain: This meansthat your medical provider needs moreinformation (usually more tests) to findout what’s going on.ɠ False positive: Your test results showthat you have a certain condition, butyou don’t really have it.ɠ False negative: Your test results showthat you do not have a certain condition,but you really do have it.Next stepsYour provider will determine next stepsonce they review your lab results.Those might be a change in medicationor diet or more tests to look into anypotential problems.Remember, if you don’t understandthe wording or the numbers in your testresults, ask your health care provider.The more you understand, the better youcan take care of yourself and your family. TSOURCE: MedlinePlusBY THE NUMBERS ALS—short for amyotrophic lateral sclerosis—is a rare but serious disease that attacks nerve cells in the brainand spinal cord. It’s also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, after theNew York Yankees player who had the disease.The disease affects voluntary muscle movement. That can meananything from chewing, walking, running, or talking.ALS symptoms get worse over time.Early symptoms may include muscle weakness or stiffness. Butas more muscles are affected, people lose their strength and theability to speak, eat, move, and even breathe.While there isn’t a cure for ALS, there are treatments that canmake living with the condition somewhat easier. Those can includea combination of medication, physical and speech therapy, andnutritional and breathing support.Researchers supported by NIH’s National Institute ofNeurological Disorders and Stroke and several other institutes andcenters are working hard to learn more about the disease and findanswers to help people with ALS.ALS affects 5 out of every100,000 people worldwide.Between 16,000–17,000Americans have ALS.10%About 10 percent of all ALScases are inherited.ALS most commonly developsbetween the ages of 55 and 75.90%90 percent or more ALS casesoccur randomly without anyrisk factors.SOURCE: National Institute of Neurological Disorders and StrokeFall 2019NEWmagazine.medlineplus.gov5

Commonly prescribed antidepressantsand how they workSSRIs are prescribed most oftenWhat are they?Antidepressants are prescribed for mood conditions suchas depression and anxiety, as well as for pain and sleepingtroubles. You may have to try a few different ones beforeyou and your provider find the best one for you.How do they work?Older antidepressant medications include tricyclics,tetracyclics, and monoamine oxidase inhibitors (MAOIs).They are prescribed less often than other medicationsbecause they tend to cause more side effects. However,they work better for some people.A recent survey found that antidepressant usewas twice as common among women than men.— Centers for Disease Control and PreventionAntidepressants can help balance chemicals in ourbrains. This can lead to improved moods, concentration,and sleep. It may take a few weeks (often four to six) forthese medications to fully work.Possible side effects:Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) arethe most prescribed type of antidepressant and include:ɠ Paroxetineɠ Fluoxetineɠ Escitalopramɠ Citalopramɠ SertralineNext stepsSerotonin and norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors(SNRIs) are similar to SSRIs. Common ones includevenlafaxine and duloxetine.6Bupropion works differently than SSRIs or SNRIs. It alsotreats seasonal affective disorder and helps peoplestop smoking.Fall 2019 NIH MedlinePlusɠ Nausea and vomitingɠ Weight gainɠ Diarrheaɠ Sleepinessɠ Sexual problemsIf you or someone you know thinks they have depression,talk to your health care provider as soon as possible.Antidepressants, talk therapy, or a combination of thetwo may help. TSOURCES: MedlinePlus; National Institute of Mental HealthIMAG E: ISTOCKTREATMENT OVERVIEW Antidepressants are among themost searched medications on the internet. But there isa lot of information out there to sift through.We've pulled together some basic information fromMedlinePlus and the National Institute of Mental Healthon common types of these medications.

8 health questions to ask yourfamily membersYour family medical history may help you reduce risk and get help earlyIMAG E: ISTOCKIf a family member does not wantto discuss their health issues aroundother people, ask to have a privateconversation. Try to remind themof the importance of having a familyhealth history.But remember that health can bedifficult to discuss. Listen carefullyand try to be as respectful andpatient as possible.For adopted children or childrenof sperm or egg donations, healthrecords may be available fromthe original adoption or donationagencies. Genetic testing can alsohelp determine certain conditions.HEALTH TIPS It's the time of yearwhen many families gather for theholidays, which means it's also agreat time to learn about your familyhealth history.Discussing medical conditions ordiseases among family membersmay help determine if you have ahigh risk for a disease.That’s because our genes,which we inherit from our birthmother and father, are importantin determining our health. Forexample, sickle cell disease—ablood disorder—is caused by genemutations that come from a parent.But just because your parentsor other family members have acondition doesn’t mean you have itnow or will in the future. That’s whylearning about your health historyand risk and sharing that informationwith a doctor is important.A family medicalhistory can:ɠ Show early warning signs of acondition or diseaseɠ Provide health care providerswith information so they canrecommend treatment, andassess and possibly reduce riskɠ Help improve family members’lifestyles to potentially reduce riskHow to collect a familymedical historyThere are different ways to collectfamily health information. You canchoose one family member to collectall the health information fromvarious relatives or have each relativefill out their own health record. Youcan also create a checklist that isorganized by medical condition.What are good healthquestions to ask yourfamily? Here are a fewyou can start with:1. What is your ethnic background?2. Where do you live?3. Where were you born?4. How old were you or yourrelative when they developedthe medical condition(s)?5. How many people in your familyhave had the same conditionsor diseases?6. Have you or any of your familymembers been tested for geneticmutations (cell changes)?7. How old were your deceasedrelatives when they died, andhow did they die?8. What diseases or medicalconditions have you had? TSOURCES: MedlinePlus; Genetics HomeReferenceFall 2019NEWmagazine.medlineplus.gov7

STUTTERINGSpeakingSpeaking upupabout stuttering“Stuttering gets no respect as adisorder,” says stuttering expertDennis Drayna, Ph.D. “People think ofit as a mild condition. They don’tsee that it can have a profoundnegative impact on the lives of thosewho have it.”8Fall 2019 NIH MedlinePlusDennis Drayna, Ph.D., is a scientist emeritus with NIH’s NationalInstitute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders.What causes stuttering?Stuttering isn’t caused by stress or anxiety, but they canmake it worse.“A mild stutter can become severe when the personhas to give a speech to 500 people. Raising anxiety levelstends to decrease fluency,” Dr. Drayna says.Stuttering also runs in families. Studies have foundthat 60% of those who stutter also have a familymember who stutters.“That’s why the genetic approach seemed to be theonly entree into solving this problem when I startedmore than 20 years ago,” Dr. Drayna says.IMAGE: COURTESY OF N ID CDHe should know. Stuttering runs in his own family,including his sons, brother, and uncle.As a senior researcher with NIH’s National Instituteon Deafness and Other Communication Disorders, hespent more than two decades researching this puzzlingcondition and identifying mutations in several genesthat are linked to it.Stuttering, a speech condition that causes people torepeat or stumble over certain sounds, syllables, orwords, is unique, Dr. Drayna says.It’s not like other communication or speech disorders.“They don’t have problems with grammar, syntax,articulation, or pronunciation,” he says. “They knowexactly what they want to say, they just can’t say it at therate they would like.”It’s why Dr. Drayna feels that calling stuttering aspeech disorder is an incomplete description.“In many circumstances, even severe stutterers canspeak very fluently,” he notes. “If you ask them torecite the pledge of allegiance with others, or sing,their speech is often fine.”There’s a saying among those in the stutteringcommunity that no one stutters when they talk to theirdog, Dr. Drayna adds. Maybe it’s because people knowthe dog isn’t judging them, he says.

STUTTERING4 common myths and facts about stuttering"There’s a great deal of misunderstanding about stuttering," says Dennis Drayna, Ph.D.,a scientist emeritus with NIH’s National Institute on Deafness and Other CommunicationDisorders and an expert on the genetics of stuttering.Here are some common misconceptions and facts:Myth: It’s a psychological problem caused byanxiety, stress, or nervousness.Truth: While anxiety or stress may worsen stuttering,it doesn’t cause it. Stuttering often starts in childhood.As children grow older, many become anxious andashamed after they experience negative reactionsfrom people around them. Treatment for stutteringoften includes counseling to help deal with otherpeople’s damaging reactions.Myth: A person who stutters just needs to relaxand calm down before they speak.Truth: Telling a person who stutters to “just relax”or “calm down” makes it worse because it increasesthe pressure on them to speak normally. “It creates avicious cycle,” says Dr. Drayna. Stuttering doesn’t happenbecause people are scared of speaking in public, he says.It is likely linked to subtle changes in the brain, and in atleast some cases, to mutations in specific genes.Back then, the data about genetic factors was skimpy. Inthe last 15 years, the data has grown a lot, he says.What the data saysDr. Drayna’s research group found mutations in fourgenes linked to stuttering. All of these genes controlwhat is called intracellular trafficking—how importantmolecules inside a cell move around in various pathways.Unfortunately, the genes’ mutations mean the geneproducts don’t do a very good job of directing traffic. Sothat slows down cell functioning and somehow affects thespeech process.“We can find a mutation in one of these genes in about20% of people who stutter,” he says, which is a largeamount for a disorder with a complex inheritance patternsuch as stuttering. Dr. Drayna’s group has since found twomore genes that also seem to be linked to stuttering.Does that mean people could be tested for a stuttering gene?Myth: People who stutter are not smart.Truth: Stuttering has nothing to do with intelligence.Just because a person has trouble speaking doesn’tmean they are confused about anything. They knowwhat they want to say, but there’s a glitch in their abilityto produce smooth speech. Stuttering has affectedscientists, actors, writers, and politicians, many ofwhom have achieved great things.Myth: It’s OK to finish a person’s sentence forthem if they’re stuttering.Truth: “Finishing a sentence for a personwho stutters is the worst thing you can do. It’sdemeaning—worse than telling someone just to relax,”says Dr. Drayna. “Would you tell someone walking witha brace on their leg to just walk better?” The precisecauses of stuttering are still poorly understood, butat least some cases are linked to genes that controlfunctions within the brain’s cells. Until a cure is found,speech therapists can often provide techniques thatcontrol or reduce stuttering.“The answer is yes, but it might not be very helpful tothem,” Dr. Drayna says. In his studies, not everyone whohad a stuttering gene in fact stuttered, especially thefemales. Males who stutter outnumber females by fourto one.Striving for better treatmentDr. Drayna, who has since retired from NIH and continuesto serve as a scientist emeritus, hopes that researcherswill one day understand enough about what is happeningat the cellular and molecular level so that a better therapyfor stuttering can be developed.In the meantime, he encourages those who stutter toseek out a speech therapist for help.“Stuttering can be a difficult condition to treat, butmany speech-language pathologists (SLPs) are highlyskilled and have lots of tools.” Dr. Drayna recommendsseeking an SLP who specializes in stuttering. TFall 2019NEWmagazine.medlineplus.gov9

STUTTERINGStuttering: What you need to knowStuttering is a complex speech condition thatcan cause a person to get stuck trying to saycertain sounds, syllables, or words.People who stutter know exactly what theywant to say, but they have trouble producing anormal flow of speech. Sometimes they repeatcertain sounds. They may also experience aninterruption, called a block, when they can’t saythe word or sound they want to use.How many people stutter?About 3 million Americans stutter, and stutteringaffects four times as many males as females.When does it happen?Developmental stuttering is most common. Itoccurs in children between the ages of 2 and 6, asthey develop their language skills. It can last froma few weeks to many years—even into adulthood.About 75% of children recover from stuttering.Neurogenic stuttering is rarer and can be causedby a stroke or serious head or brain injury.What causes stuttering?The exact cause of stuttering is not well understood,but genetic factors are clearly involved. About 60%of people who stutter also have a family memberwho stutters.Researchers with the National Instituteon Deafness and Other CommunicationDisorders (NIDCD) have identified mutationsin four different genes that are linked tostuttering that persists throughout life.How is it diagnosed?Stuttering is usually diagnosed by aspeech-language pathologist, a health careprofessional who tests and treats individualswith voice, speech, and language disorders.How is it treated?There currently is no cure for stuttering.Speech-language pathologists can usea variety of treatments specialized forchildren, teens, and adults.Antidepressants and anti-anxiety drugs mayalso be prescribed. But a study funded byNIDCD found drug therapy largely ineffectivein controlling stuttering long term.Electronic devices that fit into the earcanal and slightly alter the sound of aperson’s voice can be used on a short-termbasis. In addition, many people find successthrough a combination of speech therapyand support groups. T3 millionAmericans stutterStarts at ages2–6 yrs75%of childrenrecover fromstuttering60%also have afamily memberwho stuttersTips for helping a child who stuttersAlthough there is currently no cure for stuttering, thereare treatments that can be customized to a child’s age andother factors.Seeking early treatment is important. It may preventdevelopmental stuttering (when a child is young) frombecoming a lifelong problem.Health professionals generally recommend that a child beevaluated if he or she has stuttered for three to six months.They also recommend an evaluation if there is a familyhistory of stuttering or related communication disorders.Treatment often involves teaching parents ways tosupport their child as they develop their language skills.Parents are often encouraged to:ɠ Listen attentively when the child speaks. Be patient. Trynot to interrupt or finish a child’s sentences. Focus onthe content of the message rather than how it is said.10Fall 2019 NIH MedlinePlusɠ Speak in a slightly slowed and relaxed manner.This can help reduce the time pressure the childmay be experiencing.ɠ Provide a relaxed home environment that allowsmany opportunities for the child to speak. Thisincludes one-on-one time with a parent.ɠ Be less demanding on the child to speak in a certainway or to perform verbally for people. This isespecially important if such pressure upsets thechild or causes them more difficulty in speaking. TIMAGE: AD OBE STOCKSpeaking slowly and listening carefullyare first steps

STUTTERINGWhy do so manyof my familymembers stutter?NIH research in west Africanfamily and community helpsidentify stuttering geneJIMAGE: COURTSEY OF JOE LUKON Goe Lukong had a simple question.The answer he got would changehis life.What Joe wanted to know was,why did he and so many members of hislarge, extended west African family allstutter? Siblings, aunts, uncles, nephews,cousins—the list went on and on. “Is itpossible there could be a genetic link?”he wondered.As it turned out, there definitelywas a link.The genetic information gatheredfrom Joe’s family allowed NIHresearchers to discover another genelinked to stuttering.Searching for answersIt was 2002, when Joe, then 37, wasliving in a small rural town in theAfrican country of Cameroon.He wanted to find out more about hisstuttering condition—P E R S O N A L and find answers for hisS T O R Y family. So he decided toparticipate in an onlineresearch symposium where stutteringexperts offered to answer people’squestions about the disorder.When one of the experts sawJoe’s question about his family,they forwarded it to Dennis Drayna,Ph.D., at NIH’s National Institute onDeafness and Other CommunicationDisorders (NIDCD).The fourth geneDr. Drayna, who was studying thegenetics of stuttering, quickly realizedthat Joe’s huge family could be criticalto discovering more genes that could becausing the disorder.Shortly after, Dr. Drayna and his teamtraveled to Cameroon. There they tookblood samples from more than 150people, including 50 in Joe’s familywho stuttered.The Lukong family, says Dr. Draynanow, “allowed us to find the fourth gene”linked to stuttering.Participating in the research had a hugeeffect on Joe’s life too.Getting help and confidenceIt helped him understand stutteringbetter. It also gave him access to freespeech therapy and the confidence tohelp others who stutter.“You have to understand, I grew upin a small rural town,” Joe says. “Inour school, teachers were not surehow to deal with people with speechproblems. They would laugh at themand then the students would follow.”As for speech therapists, there wereonly a few in the entire country andonly in the bigger cities.Joe said he tried to hide his stuttering“because I feared people would have anegative impression of me.”But after the NIDCD research, hehelped organize a stuttering conferencethat helped more than 100 people inCameroon get speech therapy.“It helped me realize I wasn’t alone.It helped me let go of my fear ofstuttering,” he says.Joe Lukong (far back center inbaseball cap) connected withNIH researchers through anonline stuttering forum.Joe, his wife, and son now live inMinnesota, where he works withpeople with mental disabilities.His advice to those who stutter:“Don’t let it keep you from achievingyour goals. The people who reallymatter will care what you have to say,not how you say it.” TFind Out Moreɖ MedlinePlus: � National Institute onDeafness and OtherCommunication th/stutteringɖ Speaking of Science Podcast:Genetics of n-disordersɖ ClinicalTrials.gov: ond stutteringFall 2019NEWmagazine.medlineplus.gov11

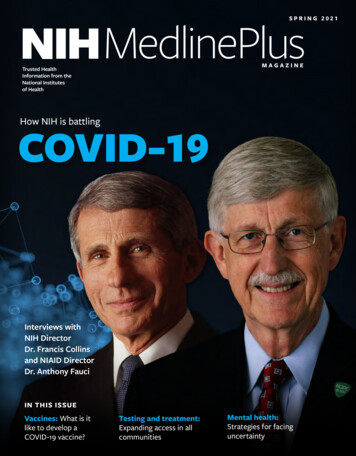

REACHING GREAT HEIGHTSwith anxiety and depressionHow NBA star Kevin Love is normalizing theconversation around men's mental healthKevin Love has achieved a lot in 31 years. He's a five-timeNational Basketball Association (NBA) All-Star. He won anNBA championship with the Cleveland Cavaliers in 2016.He's also a basketball world champion and a U.S. Olympic gold medalist.But he has experienced challenges. He lives with depression andanxiety and has suffered from panic attacks. He even had one duringan NBA game.Recently, he opened up about his mental health and sharedhis story with the public. By speaking out about his ownexperiences, he has sparked a movement to raiseawareness about mental health—especially for men andathletes. He talked to NIH MedlinePlus magazineabout his journey.Your panic attack during an NBAgame was a turning point for you.Can you tell us about that?It's a really scary thing to feel somethinghappening to your body and have no ideawhat's going on. Especially in the middle of anNBA game in front of thousands of people.In that moment, my heart was racing.I couldn't catch my breath. I thought I washaving a heart attack. Even after it was over,I didn't know that I had had a panic attack.I thought there was something physicallywrong with me and it wasn't until everythingtested out OK physically that I realized therewas something else going on that I neededto address.What has been helpful for youin dealing with your anxiety anddepression?I work with a therapist and I am one of thepeople whom medication has helped. I knowpeople have different outlooks when it comesto medication. It's a very personal decision,but for me it has helped a lot.12Fall 2019 NIH MedlinePlus

ANXIETY"We need to share our stories and make surepeople know they are not alone."IMAGES: DEREK KET TEL A– Kevin LoveTaking care of my total health has also been a reallyeffective tool. I try to meditate regularly and get enoughsleep. Exercise is a great way that I let off steam and feelgood about myself, and not just because I'm an athlete.I'm also very focused on my diet and eating well.So to change that, we need to keep talking about itmore, especially as men. We need to share our stories andmake sure people know they are not alone. There is a vastcommunity that empathizes with them and understandswhat they are dealing with.What advice do you have for other men andboys who might experience similar issues?Since you began speaking out, have youheard from other men or boys who arefacing these challenges?I encourage everyone to speak their truth. One saying Ialways default to is "nothing haunts you like the thingsyou don't say." When I was younger, I held it in becauseI was afraid of what my friends and family would say andwhat the people around me would think. I was worriedwhat my teammates and other people on the court wouldthink of me, too.Now, I feel more comfortable in my own skin than I everhave. It's really important to know that others are goingthrough it too and that a lot of good can come throughyour experience.Could you talk about fighting the stigmaattached to mental health/mental illness,particularly among men?Mental health is not something that has traditionallybeen talked about among men. We're taught that we'resupposed to bury our feelings and not be vulnerable.If you look at the past, things like melancholy,depression, anxiety, and mood disorders wereactually seen as endearing or as something thatcould lead to great things. I read a book aboutPresident Abraham Lincoln called "Lincoln'sMelancholy" that talks about his depressionand the role it played in driving him togreatness. It was eye-opening for

Trusted Health Information from the National Institutes . of Health. 8 Speaking up about stuttering Latest updates from NIH . 12 Reaching great heights How NBA star Kevin Love is normalizing the conversation \naround men's mental health . 18 Lewy body dementia What you need to know