Transcription

NIH MedlinePlusSPRING 2021MAGAZINETrusted HealthInformation from theNational Institutesof HealthHow NIH is battlingCOVID-19Interviews withNIH DirectorDr. Francis Collinsand NIAID DirectorDr. Anthony FauciIN THIS ISSUEVaccines: What is itlike to develop aCOVID-19 vaccine?Testing and treatment:Expanding access in allcommunitiesMental health:Strategies for facinguncertainty

NIH recognizes itsCOVID-19 heroesA special message from NIH DirectorDr. Francis CollinsWHO WE AREThe National Institutes of Health (NIH) is the nation’spremier medical research agency, with 27 differentinstitutes and centers. The National Library of Medicine(NLM) at NIH is a leader in research in biomedicalinformatics and data science research and the world’slargest medical library.NLM provides free, trusted health information toyou at medlineplus.gov and in this magazine. Visit us atmagazine.medlineplus.govThanks for reading!NIH Director Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D.We are grateful to our entire NIH staff andcommunity and to you, our readers. A key partof addressing COVID-19 is giving people accessto trusted health information like that from NIHMedlinePlus magazine, which is produced by NIH’sNational Library of Medicine. Make sure to explorethe magazine’s website, magazine.medlineplus.gov,and NIH’s COVID-19 website, covid19.nih.gov, forthe latest updates about COVID-19.Thank you for reading!Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D.Director, National Institutes of HealthCONTACT 000CONNECT WITH USFollow us on /Follow us on Twitter@NLM NIHEditor’s note: For the latest COVID-19guidance, visit the Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention website (cdc.gov).Articles in this publication are written by professionaljournalists. All scientific and medical informationis reviewed for accuracy by representatives of theNational Institutes of Health. However, personaldecisions regarding health, finance, exercise, and othermatters should be made only after consultation withthe reader’s physician or professional advisor. Opinionsexpressed herein are not necessarily those of theNational Library of Medicine.IMAG ES: N IHWELCOME TO NIH MEDLINEPLUS MAGAZINE!Written with health consumers in mind, thismagazine shares emerging research and healthupdates from the National Institutes of Health. I amhonored to be on the cover of the spring 2021 issuealong with my colleague Anthony S. Fauci, M.D.Inside, we provide the latest NIH news on COVID-19.Since news of SARS-CoV-2—the virus thatcauses COVID-19—first emerged, we at NIH haveworked around the clock to respond to it fromall research angles: vaccines, testing, treatment,health disparities, mental health, and more. Nearlyevery one of NIH’s 27 institutes and centers hascontributed in some way over the last year-plus toCOVID-19-related research, with the ultimate goalof improving the health of all Americans.In this issue, we recognize the heroes in the NIHcommunity whose tireless work has advancedthe science around COVID-19 and related healthresearch areas. Those include Dr. Fauci, his teamat the National Institute of Allergy and InfectiousDiseases, and many of the directors, researchers,and other integral NIH community members whoare interviewed in this issue.

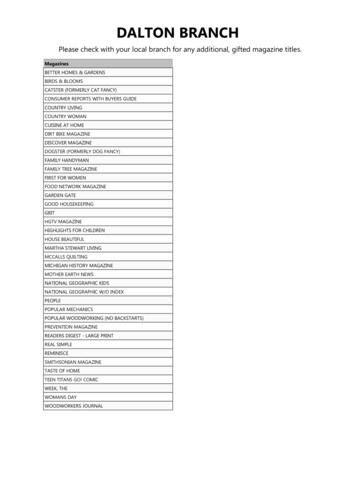

Trusted HealthInformation from theNational Institutesof HealthinsideSPRING 2021Volume 16Number 16From left to right: President Joe Biden meets with NIH’s Anthony S. Fauci, M.D.; White House CoronavirusResponse Coordinator Jeff Zients; NIH’s Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D.; and Kizzmekia S. Corbett, Ph.D.F E AT U R E SD E PA RT M E N T S06 Research is the key04 To your healthInsights from NIH DirectorDr. Francis Collins10 NIH’s Dr. Fauci on theCOVID-19 battleNIAID director talks virus variants, lessonslearned, and public health careers18 NIH ramps up testing forat-risk populationsRADx-UP funds COVID-19 communityand rapid test pilot programs24 Managing the uncertaintyof COVID-19NIH tracks short- and long-termimpact on mental healthNews, notes, & tips from NIH28 From the labLatest research updates from NIH30 NIH on the webFind it all in one place!31 Contact usNIH is here to helpNational Libraryof Medicine (NLM)Director Patricia FlatleyBrennan on data-drivenhealth and NLM’s role inthe pandemic fight16

toyourhealthNEWS,NOTES,& TIPSFROM NIHThe COVID-19 vaccines:What you need to knowWhat is an mRNA vaccine?The Moderna and Pfizer vaccines aremessenger RNA vaccines, also calledmRNA vaccines. They contain geneticmaterial or “instructions” that teachcells in your body to make a harmlesspiece of spike protein. That piece ofprotein, in turn, tells your immunesystem to produce the antibodiesneeded to protect you. After the pieceof protein is made, the cell breaks downthe instructions and gets rid of them.How long have researchersbeen studying mRNAvaccines?The Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19vaccines that are currently availablein the U.S. use technology thatresearchers at the National Institutes ofHealth have been studying for decades.This technology can fight the spikeproteins that stick out from the surfaceof the COVID-19 virus.4Spring 2021 NIH MedlinePlusWhat is a viralvector vaccine?The Johnson & Johnson vaccine,which is a viral vector vaccine, worksin a similar way. Instead of RNA, itcarries a slightly different version ofanother virus than the one that causesCOVID-19. This different virus, calleda “viral vector,” carries the same typeof important instructions that mRNAvaccines do. Once the instructionsare inside your cells, they tell them tomake a harmless piece of spike protein,which then triggers your immunesystem to make protective antibodies.Can the COVID-19 vaccinesgive you COVID-19?The COVID-19 vaccines cannot giveyou COVID-19. The symptoms thatsometimes come after you’ve had avaccine shot are normal and a signthat your immune system is working.Call your health care provider or 911 ifyou are concerned about an allergic orother reaction, which is very rare.How do I know if I’m fullyvaccinated?People are considered fully vaccinatedtwo weeks after their second shot ina two-dose series, like the Pfizer orModerna vaccines, or two weeks afterIn the lab of National Institutes ofHealth-supported researcher JasonMcLellan, Ph.D., whose work at theUniversity of Texas-Austin supportedCOVID-19 vaccine development.a single-shot vaccine, like the Johnson& Johnson vaccine.Where can I learn moreabout getting a COVID-19vaccine?Visit vaccines.gov or your local statehealth website to learn where andwhen you can get a COVID-19 vaccine.If you have more questions about theCOVID-19 vaccine, visit the Centersfor Disease Control and Preventionwebsite and talk to your health careprovider. TSOURCES: National Institutes of Health;Centers for Disease Control and Prevention;Vaccines.govIMAG E: UNI VER SIT Y OF TEXAS -AUSTINRESEARCH Vaccines work byteaching your body’s immune systemto recognize and fight back againstgerms, such as a virus, that can causeserious illness. By getting vaccinated,you develop protection against adangerous illness without having toget sick.

YourCOVID-19GlossaryHEALTH TIPSSARS-CoV-2: Up closeEFFICACY—how well something, like avaccine or treatment, works in a clinical trial.VARIANT— a virus that has changedfrom its original version. A variant usually hasa change in genetic material, which results in adifferent amino acid.ANTIBODY—a protein our immunesystems make to fight off germs. Antibodiescan stay in our bodies and protect us fromfuture infection.UNDERLYING CONDITION—a condition that someone already has, likediabetes or asthma, that puts them at greaterrisk for complications from an infection.THERAPEUTIC AGENT— a therapyor treatment for a medical condition. Atherapeutic agent can help you feel betterand fight off a disease.BASIC RESEARCH—science thathelps us understand living systems and lifeprocesses better. This knowledge leads tobetter ways to predict, prevent, diagnose,and treat disease. Basic research was key toCOVID-19 vaccine development. TSOURCE: National Institutes of HealthDID YOU KNOW?IMAG ES: AD OBE STOCKCOVID-19 vaccines do notchange or interact withyour DNA in any way.SOURCE: Centers for DiseaseControl and PreventionRESEARCH The genetic blueprint material for SARS-CoV-2is called RNA (yellow spirals). The RNA contains informationto specify the amino acids that make up the proteins, whichare the actual building blocks for the virus particle. The RNAis protected in the virus envelope (black outer ring) untila potential host cell is found. The envelope is made up ofseveral proteins, including envelope protein (blue spikes);membrane protein (yellow spikes); and spike glycoprotein orspike protein (red, tall spike). The spike glycoprotein helpsthe virus latch onto and gain entry into the host cell, so thatthe virus can infect the cell.SOURCES: National Institutes of Health; Scripps ResearchSpring 2021 magazine.medlineplus.gov 5

I N T E RV I E W: F RA N C I S CO L L I N S, M . D. , P H . D.RESEARCHistheKEYInsights from NIH DirectorDr. Francis CollinsHow NIH has responded to the worst pandemic in more than 100 yearsSINCE THE FIRST NEWSof SARS-CoV-2, the virus thatcauses COVID-19, surfaced, theNational Institutes of Health(NIH) has spearheaded researchto help understand, treat, andprotect people from the virus, andexamine its wider impact on ourhealth and communities.NIH Director Francis S. Collins,M.D., Ph.D., spoke about how theorganization’s 40,000-plus staffand the greater research communityhave responded to everything fromvaccines and testing to mentalhealth and health disparities. Healso explains what’s next on thehorizon for COVID-19 research andhow NIH is already preparing forfuture pandemics.How is NIH promoting testingand vaccination in communitiesaround the U.S., especially withunderserved and vulnerablepopulations who are more likelyto be affected by COVID-19?African Americans, Latinos, andNative Americans have shoulderedan unduly serious burden from this6Spring 2021 NIH MedlinePlusterrible pandemic, and we at NIHneed to be doing everything we can,through research, to understand waysto intervene and provide assistance.With regard to clinical trials, wewant to be sure that if we’re testinga treatment or a vaccine, that thoseinterventions are being tested in allcommunities, including the mostvulnerable populations. We’veworked hard to include that kind ofcommunity engagement, to try tobe sure that those hard-hit groupshave a chance to have their questionsanswered and to consider signing up.In the face of this urgent situation,that has been challenging, but I thinkwe’ve made real progress.For this effort, I’ve got to say, muchcredit goes to the institutes at NIHthat have taken this on—particularly toGary Gibbons [M.D.] of the NationalHeart, Lung, and Blood Institute andEliseo Pérez-Stable [M.D.] of theNational Institute on Minority Healthand Health Disparities. They havealso co-led CEAL, which stands forthe Community Engagement AllianceAgainst COVID-19 Disparities. Itfocuses on addressing misinformationaround COVID-19 andquestions like, how do we buildtrust [within] these hard-hitcommunities by engaging withtheir community leaders so that wecan really listen to their concerns andprovide answers to the skepticism thathas existed in those communities?With regard to testing, one of thereasons that this disease has hit[underserved] communities so hard isbecause they haven’t really had accessto point-of-care testing that wouldtell a person, “It would be better notto go to work today because you’realready infected with this virus, andif you do go out in the community,there’s a chance of further spreadingit.” We’ve put together a programcalled RADx-UP—Rapid Accelerationof Diagnostics for UnderservedPopulations—which is already outin the field. More than 60 different[funding] awards have been madeto try to do this kind of communityengagement and make testingavailable. We will be able to assesshow convenient access to testing willbe received, and how it can change thecourse of community spread.

I N T E RV I E W: F RA N C I S CO L L I N S, M . D. , P H . D.“We want to besure that if we’retesting a treatmentor a vaccine, thatthose interventionsare being tested inall communities,including themost vulnerablepopulations.”– Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D.IMAG ES: N IHCan you describe theAccelerating COVID-19Therapeutic Interventions andVaccines (ACTIV) program?In March 2020, looking at thelandscape of what was being doneto develop treatments, there werea lot of small studies and hundredsof ideas about therapeutic agentsthat might work. But there wasno prioritization process, nocoordinated way to get thoseagents into clinical trials that wouldbe well-designed, randomized,placebo-controlled—all the thingsyou need if you’re really going totrust the answer. That is not whatwas needed for the worst pandemicin 102 years.I called up a lot of my colleaguesin academia and in industry, andin a very short period of time, weassembled a group to talk aboutwhether all sectors could becomereal partners in this effort. After aninitial positive discussion, it tookjust two weeks for this partnershipto come into being. It’s calledACTIV. This has intenselyinvolved about a hundred people,about half of them from industryand half from government andacademia. They pretty muchdropped everything else. Theyorganized themselves into fourvery intense working groups onpreclinical issues, clinical issues,clinical trials, and vaccines. TheFoundation for NIH providedexpert program management,which made the whole enterprisework remarkably well.All of that has now gotten usto the point where we doknow a lot of treatments thatdon’t work—and that’s reallyimportant—and a few that reallydo: remdesivir, dexamethasone,high-dose heparin for hospitalizedpatients, and monoclonalantibodies for outpatients.That’s a pretty impressiveHow to combatCOVID-19 stress:Dr. Collins shares his tipsOn music: “Music is a great way tounload some of the stress. For me,that can happen by playing my babygrand piano or my guitar. I seek thoseout when I need to get up out of myhome office chair, and at least for afew minutes use a different part ofmy brain.”On physical activity: “I have a trainerwho Zooms in twice a week at 5:45 inthe morning. By the end of an hour,I have been completely reduced to apuddle of sweat by weight training andcardio. But it makes me feel alive againand ready to face the day. And on theweekend, if it’s not too cold, I’ll get onmy bike with my wife, Diane, and we’llpedal 15 to 20 miles together.”On finding support withrelationships: “I’m very fortunateto have a soul mate in Diane, who iswalking this road with me. She hasthe amazing ability, when I’m having atough day, to provide a listening earand wise counsel. I hope I do the samefor her sometimes too.”Above: Dr. Collins performs with opera singerRenée Fleming in 2018.Spring 2021 magazine.medlineplus.gov 7

I N T E RV I E W: F RA N C I S CO L L I N S, M . D. , P H . D.out there about resources that can help people who arestruggling with anxiety, depression, and fear.This won’t be our last pandemic, so we need toidentify what we can learn from this and what kind ofinterventions would be most helpful for people who aregoing through this kind of struggle, both now and in thefuture. So, as part of our agenda, along with vaccines anddrugs that might be effective treatments, we also need themental health issues to get the same kind of attention.We’re working hard on that. Josh Gordon [M.D., Ph.D.],the director of NIMH, has been front and center, andis helping to design the next generation of pandemicresearch studies at NIMH.Many people have been working around the clock onthe vaccine and other COVID-19 research. Who aresome of the NIH heroes who are part of this process?menu, but it’s not big enough. We’re still deep into that,even a year later, because this is not over and we want tobe sure we have tested every idea.How is NIH research tackling the issue of mentalhealth right now?There are so many consequences of COVID-19 that havemade life extremely difficult for everybody across theworld, and certainly that includes the U.S. Hardly anyonehas been untouched, whether it is by their own illnessor that of a family member, the economic distress that’sfallen on so many people, or consequences of isolationand being in a circumstance that none of us expectedwould be part of our daily life but now is. You can’tlook at this circumstance and not [see] that [an impacton] mental health is one of the big consequences ofCOVID-19. Certainly, surveys have shown that the vastmajority of people are feeling significant stress.NIH, of course, has an entire institute devoted tothese issues—the National Institute of Mental Health(NIMH)—and NIMH has worked hard to get information8Spring 2021 NIH MedlinePlusHow does NIH track and prevent future pandemics?We need to learn the lessons from this dreadfulexperience so that, if there’s a future pandemic, we willbe as prepared as possible. We’re already consideringwhat those lessons might be. One of the things we reallyhave not developed for this pandemic, because the timehas been so short, is an array of really powerful antiviraldrugs that would be very specific in knocking out thiscoronavirus. We need to push that agenda right now andare starting that process.IMAG ES: N IHDr. Collins on Bike to Work Day in 2018.There are many! Some of the first who come to mindare those at NIH’s Vaccine Research Center (VRC) who,within a day after the posting of the sequence of thegenome of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, went about designingwhat the vaccine would look like. They built on work theyhad pursued for many years, using messenger RNA as theway in which the vaccine could be developed. Then theycollaborated with the company Moderna. And within 63days of the initial posting of the viral genome sequence,the first patient was getting injected with a phase 1vaccine. Among those VRC heroes are Kizzmekia Corbett[Ph.D.], Barney Graham [M.D., Ph.D.], and John Mascola[M.D.], who led that effort under Tony Fauci [M.D.]’s ableoversight. And look where we are now.I have to mention Dr. Fauci himself as one of our heroes,not only for his scientific leadership, but also the wayin which he has been out there fearlessly in the publicview, providing information that is absolutely based uponevidence and truth.There are countless other folks who have been heroic.Across every NIH institute, people have droppedeverything from the kind of research they were doing andpushed forward in new directions to try to discover thingsthat we needed to know about.

I N T E RV I E W: F RA N C I S CO L L I N S, M . D. , P H . D.Technicians review test results in the Clinical Center’s Department of Laboratory Medicine.I think we’ve also learned some really interestingthings about how to do science quickly. One exampleis the development of new diagnostic tests. We wereasked by Congress in April 2020 to really pull out allthe stops with new technologies that would allow usto diagnose COVID-19 in people in a few minutes. Thatwas the program called RADx—Rapid Acceleration ofDiagnostics. And what Bruce Tromberg [Ph.D.] and histeam at the National Institute of Biomedical Imaging andBioengineering did, which had never really been donebefore, was turn NIH into a venture capital organization.We said, “OK folks, we have money, and we have experts.Bring your best ideas about how that kind of technologycan be developed.” To date, we have managed tosupport no fewer than 28 brand-new technologies to dodiagnostic testing for COVID-19, and collectively those arecontributing about 2 million tests a day—including thefirst home tests.What is something that you wishmore people knew about NIH?When you hear about a breakthrough in cancer research, ormaybe in nutrition, in diabetes, or a basic science discoveryabout the brain, if it happened in an American academicinstitution, it’s extremely likely it was funded by NIH. I wisheverybody knew that taxpayer money is making possibleadvances across the board, in ways that have greatly, overthe decades, enhanced human life and survival.I also don’t think a lot of people know that we run ahospital, NIH’s Clinical Center, which is the largest researchhospital in the world. Great things happen there: the firstdevelopment of chemotherapy, the first human gene therapy,the development of lithium and ketamine for depression, andmany more milestones. It’s an amazing place, and the peoplewho work there are truly dedicated to trying to find answersto [address] human suffering. That’s why we call ourselvesnot just the National Institutes of Health, but the NationalInstitutes of Hope. T“That’s why we call ourselvesnot just the National Institutesof Health, but the NationalInstitutes of Hope.”– Francis S. Collins, M.D., Ph.D.Spring 2021 magazine.medlineplus.gov 9

I N T E RV I E W: A N T H O N Y FAU C I , M . D.NIH’s Dr. Fauci on theCOVID-19 battleNIAID director talks virus variants,lessons learned, and careers in public healthAnthony Fauci, M.D., director of the NationalInstitute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases(NIAID), is no stranger to pandemics or infectiousdiseases. He has served as NIAID’s director since 1984 andhas worked there for more than five decades.One important skill he has brought to the COVID-19pandemic response is his ability to explain complexhealth information in clear, actionable ways. “If peoplereally want to know what’s going on,” says NationalInstitutes of Health (NIH) Director Francis S. Collins,M.D., Ph.D., “they know that Tony’s going to tell themthose facts, even if they’re not the facts that everybodynecessarily wants to hear.” Dr. Fauci recently sat down totalk about the latest COVID-19 facts and science, focusingon how new variants of the virus might affect the public,especially when it comes to vaccines.You and Dr. Collins were recentlyvaccinated against COVID-19 here at NIH.How was that experience?After the first dose, my arm, about seven hours afterthe vaccination, felt a bit achy. That lasted until thefollowing day, and toward the end of the second day, it10Spring 2021 NIH MedlinePluswas completely gone. And that was great. Twenty-eightdays later, we got the boost. That was a little bit different.I felt a little achy but not anything that interfered withmy going to work or functioning on my typical 17-hourday. It didn’t bother me. However, when I got homethat evening, I felt chilly. I don’t think I had a fever atall, but I felt chilly. So, a combination of 24 hours of thearm hurting again, a little bit of a fatigue, a little bit of amuscle ache, a little chilliness, and then by the afternoonof the second day, it was completely gone.Why is it essential for peopleto get the vaccine?That’s really very important. First of all, we’re dealing witha vaccine that has a 94% to 95% efficacy, and virtually 100%efficacy against severe disease, like hospitalization anddeath. So, the vaccine is extremely important, for your ownhealth, for the health of your family, and for those aroundyou who might be in a situation where they have underlyingconditions. It’s also important for society in general,because the more people who get vaccinated, the closeryou’re going to get to what’s called herd immunity. Namely,if we get about 70% to 75% of the population vaccinated,

I N T E RV I E W: A N T H O N Y FAU C I , M . D.“The vaccine is extremely important,for your own health, for the health ofyour family, and for those around youwho might be in a situation wherethey have underlying conditions.”– Anthony Fauci, M.D.Dr. Fauci receives the COVID-19 vaccine at NIH.we’re going to have such an umbrella of protection insociety that the virus won’t have anywhere to go. It wouldnot be able to find any susceptible people.Do you still need to wear a mask in publicafter you’ve been vaccinated?If you have been fully vaccinated, the Centers for DiseaseControl and Prevention (CDC)’s guidance now says youcan resume most activities outdoors and indoors that youtook part in prior to the pandemic without wearing a mask,except where masking is required by state, local, tribal,or territorial laws, rules, and regulations. You still need tofollow rules of your workplace and local businesses.The CDC still advises travelers to wear masks while onairplanes, buses, or trains, and calls for wearing masksin some indoor settings, including hospitals, homelessshelters, and prisons. Masks are required in these settingsas it is conceivable that you could be vaccinated and getinfected but not know it, because the vaccine is protectingyou against symptoms. You still might have some virus inyour nasopharynx [upper part of your throat, behind yournose] that could infect unvaccinated or other vulnerablepeople in congregate settings.IMAG ES: N IAID -RML; N IAIDWhat is a COVID-19 variant, and how is NIHstudying and tracking these variants?There are a lot of terms that sometimes getinterchanged—variant, strain, lineage—they all reallymean the same thing. As SARS-CoV-2 replicates, changesin its genome (often called a mutation) can occur, andsome result in a change in an amino acid that makes upa viral protein. Most mutations don’t have any functionalimpact on the virus, but every once in a while, you get aconstellation of mutations that does have significance inone way or another. This is often referred to as a variant.Some of these variants can spread more easily or havethe potential to be resistant to particular treatments orvaccines. These are the variants that we are watchingvery closely.Dr. Fauci (right) and Dr. Clifford Lane discussAIDS-related data in 1987.Multiple variants of the virus that causes COVID-19 havebeen documented in the U.S. and globally during thispandemic. We are monitoring multiple variants; currentlythere are six notable variants in the U.S., some that seemto spread more easily and quickly than other variants. Sofar, studies suggest that our currently authorized vaccineswork against the circulating variants. The Alpha variant,also known as B.1.1.7, was first recognized in the UnitedKingdom and is now the most common variant in the U.S.,surpassing in prevalence the original viruses that originallyentered this country. Cases of COVID-19 caused by othervariants first seen in other parts of the world have occurredSpring 2021 magazine.medlineplus.gov11

I N T E RV I E W: A N T H O N Y FAU C I , M . D.in relatively small numbers in this country.We are keeping a close eye on all of these, especiallythe Beta (B.1.351), Gamma (P.1), and Delta (B.1617.2)variants that may be able to evade the immune systemand certain antibody therapies to a greater extent than theoriginal virus and other variants. To be sure that we don’tget caught behind the eight ball, companies are alreadymaking variations of the vaccine directed against certainvariant strains.If public health, and science, and medicine, is somethingthat you might even have the slightest inclination to pursue,I strongly encourage young people to pursue it. It really hasto be one of the most exciting careers you could possiblyimagine, if it suits you. The reason is, it combines scienceand health in a way that has enormously broad implications.“Public health really has tobe one of the most excitingcareers you could possiblyimagine, if it suits you.”– A N T H O N Y FAU C I , M . D.When I graduated from medical school and did multipleyears of residency, including a chief residency and thena fellowship in infectious diseases, I was taking careof individual patients. It was very exciting. I still seeindividual patients. But the excitement and the thrillyou get when you’re working on something that hasimplications for millions if not billions of people, I mean,there can be nothing more exciting than that.Everything that we do, all of us, from NLM to NIAID toany of the other 25 institutes and centers, all of us who getinvolved in that are having an impact, literally, on billionsof people. So, when I see a young person who has eventhe slightest interest, I say, you better pursue it, becauseyou’re not going to imagine how exciting this could be.What are some lessons we have learnedfrom this pandemic?Well, there are always lessons that are learned, if you do itright, from one [pandemic] to another.12Spring 2021 NIH MedlinePlusMicroscopic image of a cell (blue, large circles) infected withSARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19 (red, small circles).I think one of the things that really was [evident]was the importance of the chain of fundamental basicand clinical research. I mean, to be able to use thefundamental structural biology that we focused on withHIV, the same investigators collaborated with each otherand used that structure-based vaccine design. That neverwould have happened if we hadn’t had fundamental basicresearch that started off decades ago. So, to me, that’ssuch a good example of the need to continue to fundfundamental basic research.But then there are a lot of, also, public health lessonslearned: the importance of a global health strategicnetwork and surveillance, especially the ability to dorapid, extensive, comprehensive genomic surveillance.Are there any NIH-specific sources you canrecommend for people looking for trustedhealth information?Well, particularly when you’re dealing with clinical trials,I think ClinicalTrials.gov, GenBank, and then [especiallyfor scientists and researchers] the National Library ofMedicine (NLM)’s PubMed, which I use 20 times a day.Do you have a final message that you wouldlike to convey to the public?This is a global pandemic, and it needs to be addressedat a global level. So, we should concentrate not only oncontrolling it in our own country, but we’ve got to controlit globally, otherwise it’s going to continue to come backto the U.S. with mutants and new versions of the virus. So,it will end, but it will end depending upon the effort thatwe put into it. TThis interview has been edite

WELCOME TO NIH MEDLINEPLUS MAGAZINE! Written with health consumers in mind, this magazine shares emerging research and health updates from the National Institutes of Health. I am honored to be on the cover of the spring 2021 issue along with my colleague Anthony S. Fauci,