Transcription

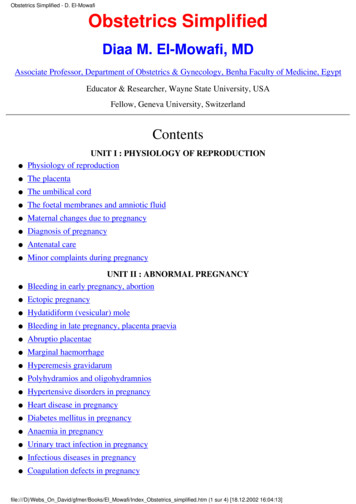

Drugs During Pregnancyand LactationTreatment options andrisk assessmentSecond editionEdited byChristof Schaefer, Paul Peters, and Richard K. MillerAMSTERDAM BOSTON HEIDELBERG LONDON NEW YORK OXFORDPARIS SAN DIEGO SAN FRANCISCO SINGAPORE SYDNEY TOKYOAcademic Press is an imprint of Elsevier

Academic Press is an imprint of Elsevier84 Theobald’s Road, London WC1X 8RR, UK30 Corporate Drive, Suite 400, Burlington, MA 01803, USA525 B Street, Suite 1900, San Diego, California 92101-4495, USAFirst edition 2001Second edition 2007Copyright 2001, 2007 Elsevier BV. All rights reservedNo part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmittedin any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwisewithout the prior written permission of the publisherPermissions may be sought directly from Elsevier’s Science & Technology Rights Department inOxford, UK: phone ( 44) (0) 1865 843830; fax ( 44) (0) 1865 853333; email: permissions@elsevier.com.Alternatively you can submit your request online by visiting the Elsevier web site athttp://elsevier.com/locate/permissions, and selecting Obtaining permission to use Elsevier materialNoticeNo responsibility is assumed by the publisher for any injury and/or damage to personsor property as a matter of products liability, negligence or otherwise, or from any useor operation of any methods, products, instructions or ideas contained in the materialherein. Because of rapid advances in the medical sciences, in particular, independentverification of diagnoses and drug dosages should be madeBritish Library Cataloguing in Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British LibraryLibrary of Congress Catalog in Publication DataA catalog record for this title is available from the Library of CongressISBN: 978-0-444-52072-2For information on all Academic Press publications visitour web site at http://books.elsevier.comTypeset by Charon Tec Ltd (A Macmillan Company), Chennai, Indiawww.charontec.comPrinted and bound in Great Britain07 08 09 10 1110 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

List of contributorsMATITIAHU BERKOVITCHDrug Information Center, Assaf Harofeh Medical Center, 70300Zerifin, IsraelHANNEKE GARBISTeratology Information Service, National Institute of PublicHealth and Environment, PO Box 1, 3720 BA Bilthoven,The NetherlandsLEE H. GOLDSTEINInternal Medicine Department C, Haemek Medical Center, Afula18101, IsraelHENRY M. HESSDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynecology, University of Rochester,School of Medicine and Dentistry, 2255 Clinton Avenue,Rochester, NY, 14618, USARUTH LAWRENCELactation Research Center, Department of Pediatrics, Universityof Rochester, School of Medicine and Dentistry, 601 ElmwoodAvenue, Rochester, NY, 14642-8777, USAPATRICIA McELHATTONThe National Teratology Information Service (NTIS),Regional Drug & Therapeutics Centre, Claremont Place,Newcastle-upon-Tyne, NE2 4HH, UKRICHARD K. MILLERPEDECS, NY Teratogen Information Service, Department ofObstetrics and Gynecology, University of Rochester, School ofMedicine and Dentistry, 601 Elmwood Avenue, Rochester, NY,14642-8668, USAASHER ORNOYIsrael Teratogen Information Service, Jerusalem ChildDevelopmental Center, Rechov Yafo 157, Jerusalem, IsraelPAUL PETERSUniversity Medical Centre Utrecht, Department of Obstetrics,Karel Doormanlaan 150, 3572 NR Utrecht, The Netherlands

List of contributorsxxiiiMINKE REUVERSTeratology Information Service, National Institute of Public Healthand Environment, PO Box 1, 3720 BA Bilthoven, The NetherlandsELISABETH ROBERT-GNANSIAAgence Française de Sécurité Sanitaire de l’Environnement et duTravail, 253 Avenue du Général Leclerc, 94701 Maisons-AlfortCedex, FranceELVIRA RODRIGUEZ-PINILLAServicio de Informacion sobre Teratogenos (SITTE), Sección deTeratología Clínica,Centro de Investigacion sobre, Anomalias Congenitas (CIAC),Instituto de Salud Carlos III, c/ Sinesio Delgado 6 (Pabellon 6),28029 Madrid, SpainMARGREET ROST VAN TONNINGENTeratology Information Service, National Institute of Public Healthand Environment, PO Box 1, 3720 BA Bilthoven, The NetherlandsCHRISTOF SCHAEFERPharmakovigilanz- und Beratungszentrum für Embryonaltoxikologie,Berlin Institute for Clinical Teratology and Drug Risk Assessmentin Pregnancy, Spandauer Damm 130, Haus 10, 14050 Berlin,GermanyHERMAN VAN GEIJNDepartment of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, VU UniversityMedical Center, PO Box 7057, 1007 MB Amsterdam,The NetherlandsCORINNA WEBER-SCHÖNDORFERPharmakovigilanz- und Beratungszentrum für Embryonaltoxikologie,Berlin Institute for Clinical Teratology and Drug Risk Assessmentin Pregnancy, Spandauer Damm 130, Haus 10, 14050 Berlin,Germany

PrefacePhysicians and all health care providers who care for women intheir reproductive years are frequently asked by concerned womenwho are planning a pregnancy, are pregnant or breastfeeding aboutthe risk of medicinal products for themselves, their unborn orbreastfed infant. These Dermatologists, Family Medicine physicians,Internists, Obstetricians, Pediatricians, Pharmacists, Midwives,Nurses, Lactation consultants, Medical geneticists, Psychiatrists,Psychologists, Toxicologists to name but a few should be wellinformed in regard to acceptable treatment options and be capable ofassessing the risk of an inadvertent or required treatment/exposure.All aspects of drug counseling are inadequately supported by various sources of information such as the Physicians Desk Reference,package leaflets or general pharmacotherapy handbooks. Formaldrug risk classifications or statements such as “contraindicated during pregnancy” may lead to a simplified perception of risk, e.g. anoverestimation of the risk or simple fatalism, and withholding of essential therapy or the prescription of insufficiently studied and potentially risky drugs may result. This simplified perception of risk, canlead to unnecessary invasive prenatal diagnostic testing or even to arecommendation to terminate a wanted pregnancy. During lactation, misclassification of drug risk may lead to the advice to stopbreastfeeding, even though the drug in question is acceptable oralternatives appropriate for the breastfeeding period are available.This book is based on a survey of the literature on drug risks duringpregnancy and lactation, as yet unpublished results of recent studies,and current discussions in professional societies dealing with clinicalteratology and developmental toxicology. The book reflects accepted“good therapeutic practice” in different clinical areas. It is written forclinical decision-makers. Arranged according to treatment indications, the book provides an overview of the relevant drugs in the referring medical area available on the market today that might be takenby women of reproductive age. The book’s organization facilitates acomparative risk approach, i.e., identifying the drugs of choice forparticular diseases or symptoms. In addition, recreational drugs,diagnostic procedures (X-ray), vaccinations, poisoning, workplaceand environmental contaminants, herbs, supplements and breastfeeding during infectious diseases are discussed in detail.The second edition has had major revisions throughout, mostsections were completely rewritten. The content has been adaptedfor an international readership. Two additional editors were enlisted;

Prefacexxvthe number of contributing authors has increased and reflects expertise in a range of clinical specialties, e.g. dermatology, obstetrics, pediatrics, internal medicine, psychiatry and many others. Moreover, mostauthors are active members of the teratology societies including theOrganization of Teratogen Information Specialists (OTIS) and European Network of Teratology Information Services (ENTIS). The format is completely different and last but not least the price is muchlower – making the book available to far greater readership.It is important to realize that the origin of this book lies in a bookpublished in German last year in its 7th edition. The success of thelatter (more than 50 000 copies sold) can be described as a bestseller – a strange term – for a book giving pertinent medical information. This also demonstrates the need to be informed in thisdifficult area of pharmacotherapeutics during pregnancy.We are grateful to Kirsten Funk, publishing editor, from Elsevier/Academic Press for providing support and advice for this projectto thrive. We thank Sue Armitage for copy editing and ClaireHutchins from Elsevier for overseeing production. The editors trulyappreciate the many hours of work each contributor has performedin the development of their chapters and with the suggested editorial revisions. Finally, the editors wish to express our appreciationto our families for providing the time and support to develop thisvolume.May the reader use this volume to examine treatment options forspecific diseases not only during pre-pregnancy but also before thewoman becomes pregnant. By providing prepregnancy counseling,the editors and authors hope that inappropriate therapeutic, occupational and/or environmental exposures will be minimized.Richard K Miller, Rochester, New York, USAChristof Schaefer, Berlin, GermanyPaul Peters, Utrecht, NetherlandsMay 2007

NoticeMedical knowledge is constantly changing. Standard safety precautions must be followed, but as new research and clinical experiencebroaden our knowledge, changes in treatment and drug therapymay become necessary or appropriate. The Authors and Editors haveexpended substantial effort to ensure that the information is accurate; however, they are not responsible for errors or omissions or anyconsequences from the application of the information in this educational publication and make no warranty, expressed or implied, withrespect to the currency, completeness or accuracy of this publication.Readers are advised to check the most current product informationprovided by the manufacturer of each drug to be administered to verify the recommended dose, the method and duration, adverse drugeffects, and interactions. Application of the content of this volume fora particular situation remains the professional responsibility of thepractitioner. It is ultimately the responsibility of the practitioner, relying on experience and knowledge of the patient, to determine dosagesand the best treatment or intervention for each individual patient.Neither the Publisher, the Editors nor the Authors assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property arising fromthis publication.

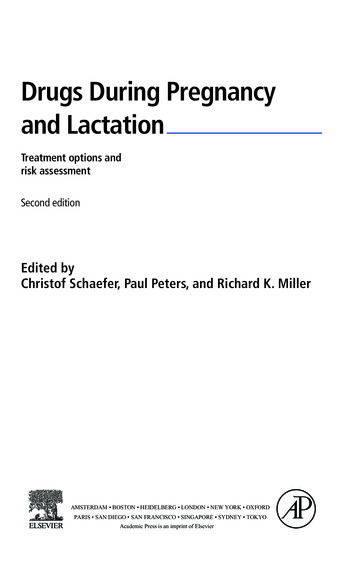

Table 1 Risk and safety of medicinal drugsCaution:Risk classification:1 Drug offirst choice2 Drug ofsecond choiceS Single doseT Potentiallyteratogenic or toxicC 22T6696676841/S1/S1/S 0660639664,766DrugChloroquine eineCotrimoxazoleCromoglycic acidCyproterone ramine111144 xylamineErgotamine tartrateErythromycinEstrogens (ascontraceptionduring urosemideLactation, see page:C 203C 242172T/S 29LactationLactation, see page:CT1T/SPregnancy, see eBenzylbenzoate etirizinChloramphenicolFetal period (from week13 after lsalicylic acid (norestriction for Amitriptyline, andother sufficientlytested tricyclic ADAmphotericin tropineEmbryonic period (untilweek 12 after LMP)DrugIn general, well-tolerated during pregnancy and lactation; nevertheless, always reevaluaterequirement for drug treatmentUse only if better-tested treatment options fail; there is often insufficient experience duringpregnancy and lactationSingle and/or low dosages probably tolerableUse only if compellingly indicated. Special prenatal diagnostics are required in case of pregnancyexposure (see referring chapter)No rational indication for use during pregnancy/lactation and/or teratogen or prenatal toxic ortoxic during lactation; special prenatal diagnostics are required in case of pregnancy exposure(see referring chapter)Fetal period (from week13 after LMP) Use table for general orientation only; review details in the referring chapter. Never use the table to decide upon termination of a pregnancy.Withdrawal from breastfeeding is rarely necessary because of maternal drug treatment. For almost all diseases there aredrugs compatible with breastfeeding; review details in the referring chapter.If not indicated otherwise, risk classifications refer to systemic drug use. Exception: drugs only available for topical application.Embryonic period (untilweek 12 after LMP) Pregnancy, see page

2222T2401 2392 8 1152 2663121T137 1302 212C1T12212C1T122198 1T/S 33 2/S1 371 1128 1T44 21 124 1T37 2T34 2649625747623630660627625T2T263 T70111T300 1C2C1212/S2/S211649666661717690653757662TTC242 2Lactation, see page:12LactationDrugNystatinOlanzapine, andother sufficientlytested ePethidine(meperidine)Phenobarbital rum inesThalidomideTheophyllineThiamazolThyroxine (L-)TinidazoleTramadolTretinoin (topical)Valproic acidVerapamilVitamin A(10 000 U/dor less)WarfarinPregnancy, see page755Peripartum405 1Fetal period (from week13 after LMP)CEmbryonic period (untilweek 12 after LMP)Pregnancy, see pageCLactation, see page:PeripartumSLactationFetal period (from week13 after LMP)Gestagenes (weighcritical progesteroneduring pregnancy;gestagenecontraceptivesduring stemicalGlucocorticoids, topicalGlyceryl trinitrateGold lazineHydrochlorothiazideHydroxy ethyl starchIbuprofenImipramineIndomethacinInsulin (human)IodinesupplementationIsoniazid vitamin B6IsotretinoinItraconazoleKetoconazoleLamotrigine (asantiepileptic)Lindane (topical)Lithium saltsLocal opaMethylergometrineMetoclopramideMiconazole NitrofurantoinNorfloxacinEmbryonic period (untilweek 12 after LMP)Drug668725642750749665627765702689696

General commentary on drugtherapy and drug risks inpregnancy1Richard K. Miller, Paul W. Peters,and Christof E. Schaefer1.1Introduction21.2Development and health31.3Reproductive stages31.4Reproductive and developmental toxicology61.5Basic principles of drug-induced reproductive anddevelopmental toxicology91.6Effects and manifestations101.7Pharmacokinetics in pregnancy121.8Passage of drugs to the unborn and fetal kinetics131.9Causes of developmental disorders141.10Embryo/fetotoxic risk assessment151.11Classification of drugs used in pregnancy191.12Paternal use of medicinal products201.13Communicating the risk of drug use in pregnancy211.14Risk communication prior to pharmacotherapeutic choice221.15Risk communication regarding the safety (or otherwise)of drugs already used in pregnancy23Teratology information centers241.16

21.1 takrco t nentruac rulation, tionPrne , himura eaordl tu r tialbeextremHear nceptilanontationMost prescribers and users of drugs are familiar with the precautionsgiven concerning drug use during the first trimester of pregnancy.These warnings were introduced after the thalidomide disaster in theearly 1960s. However, limiting the exercise of caution to the first3 months of pregnancy is both shortsighted and effectively impossible – first, because chemicals can affect any stage of pre- or postnataldevelopment; and secondly, because when a woman first learns thatshe is pregnant, the process of organogenesis has already long sincebegun (for example, the neural tube has closed). Hence, the unborncould already be inadvertently exposed to maternal drug treatmentduring the early embryonic period (Figure 1.1).This book is intended for practicing clinicians, who prescribemedicinal products, to evaluate environmental or occupational exposures in women who are or may become pregnant. Understanding therisks of drug use in pregnancy has lagged behind the advances inother areas of pharmacotherapy. Epidemiologic difficulties in establishing causality and the ethical barriers to randomized clinical trialswith pregnant women are the major reasons for our collective deficiencies. Nevertheless, since the recognition of prenatal vulnerabilityin the early 1960s, much has been accomplished to identify potentialdevelopmental toxicants such as medicinal products and to regulatehuman exposure to them. The adverse developmental effects of pharmaceutical products are now recognized to include not only malformations, but also growth restriction, fetal death and functionaldefects in the newborn.The evaluation of human case reports and epidemiological investigations provide the primary sources of information. However, for17142128354256 After ovulation14212835424956701714212842 After “missed”menstruationFigure 1.1 Timetable of early human development.After lastmenstruation

3many drugs (and even more so in the case of chemicals) experiencewith human exposure is scarce, and animal experiments, in vitro tests,or information on related congeners provide the only basis for riskassessment. The FDA has mandated that medications potentially usedin pregnant women must now be followed via pregnancy registries.This book presents the current state of knowledge about the use ofdrugs during pregnancy. In each chapter, the information is presentedseparately for two different aspects of the problem: first, seeking adrug appropriate for prescription during pregnancy; and secondly,assessing the risk of a drug when exposure during pregnancy hasalready occurred.Development and healthThe care of pregnant women presents one of the paradoxes of modernmedicine. Women usually require little medical intervention during an(uneventful) pregnancy. Conversely, those at high risk of damage totheir own health, or that of their unborn, require the assistance ofappropriate medicinal technology, including drugs. Accordingly, thereare two classes of pregnant women; the larger group requires supportbut little intervention, while the other requires the full range ofdiagnostic and therapeutic measures applied in any other branch ofmedicine (Chamberlain 1991). Maternal illness demands treatmenttolerated by the unborn. However, a normal pregnancy needs toavoid harmful drugs – both prescribed and over-the-counter, anddrugs of abuse, including cigarettes and alcohol – as well as occupational and environmental exposure to potentially harmful chemicals.Obviously, sufficient and well-balanced nutrition is also essential.Currently, this set of positive preventive measures is by no meansbroadly guaranteed in either developing or industrial countries. Whensuch primary preventive measures are neglected, complications ofpregnancy and developmental disorders can result. Furthermore,nutritional deficiencies and toxic effects during prenatal life predispose the future adult to some diseases, such as schizophrenia (St Clair2005), fertility disorders (Elias 2005), metabolic imbalances (Painter2005), diabetes, and cardiovascular illnesses, as demonstrated byBarker (1998), based upon epidemiological and experimental data.1.3Reproductive stagesThe different stages of reproduction are, in fact, highlights of a continuum. These stages concern a different developmental time-span,each with its own sensitivity to a given toxic agent.1 General commentary on drug therapy and drug risks in pregnancy1.21Pregnancy1.3 Reproductive stages

FemaleOogenesis (occurs during fetaldevelopment of mother)Gene replicationCell divisionEgg maturationHormonal influence on al influence on secretoryand muscle cellsUteruscontractilitysecretionsNervous systembehaviorlibidoChanges in uterine liningand secretionsHormonal influence onsecretory cellsReproductive stageGerm cell formationFertilizationImplantationHormonal influence onglandsNervous systemerectionejaculationbehaviorlibidoAccessory glandsSperm motility and nutritionSperm maturationSertoli cell influenceHormonal influence on testesSpermatogenesisGene replicationCell divisionMaleTable 1.1. Reproductive stages: organs and functions potentially affected by toxicantsSpontaneous abortion, embryonic resorption,subfecundity, stillbirths, low birth weightImpotence, sterility, subfecundity, chromosomal aberrations,changes in sex ratio, reduced sperm functionImpotence, sterility, subfecundity, chromosomalaberrations, changes in sex ratio, reduced sperm functionSterility, subfecundity, damaged sperm or eggs,chromosomal aberrations, menstrual effects, age atmenopause, hormone imbalances, changes in sex ratioPossible endpoints41.3 Reproductive stages

Placentanutrient transferhormone productionprotection from toxic agentsEmbryoorgan development anddifferentiationgrowthMaternal nutritionFetusgrowth and developmentUteruscontractilityHormonal effectson uterine muscle cellsMaternal nutritionInfant survivalLactationOrganogenesisPerinatalPostnatal1 General commentary on drug therapy and drug risks in pregnancyUterusyolksacplacenta formationEmbryocell division,tissue differentiation,hormone production,growthEmbryogenesisPregnancyMental retardation, infant mortality, retarded development,metabolic and functional disorders, developmentaldisabilities (e.g. cerebral palsy and epilepsy)Premature births, births defects (particularly nervous system),stillbirths,neonatal death, toxic syndromes or withdrawalsymptoms in neonatesBirth defects, spontaneous abortion, fetaldefects, death,retarded growth and development,functional disorders (e.g. autism), transplacentalcarcinogenesisSpontaneous abortion, other fetal losses, birth defects,chromosomal abnormalities, change in sex ratio, stillbirths,low birth weight1.3 Reproductive stages51

61.4 Reproductive and developmental toxicologyPrimordial germ cells are present in the embryo at about 1 monthafter the first day of the last menstruation. They originate from theyolksac-entoderm outside the embryo, and migrate into the undifferentiated primordia of gonads located at the medio-ventral surface of theurogenital ridges. They subsequently differentiate into oogonia andoocytes, or into spermatogonia. The oocytes in postnatal life are at anarrested stage of the meiotic division. This division is restarted muchlater after birth, shortly before ovulation, and is finalized after fertilization with the expulsion of the polar bodies. Thus, all-female germ cellsdevelop prenatally and no germ cells are formed after birth. Moreover,during a female lifespan approximately 400 oocytes undergo ovulation.All these facts make it possible to state that an 8-weeks’ pregnantmother of an unborn female is already prepared to be a grandmother!The embryonal spermatogenic epithelium, on the contrary,divides slowly by repeated mitoses, and these cells do not differentiate into spermatocytes and do not undergo meiosis in the prenatalperiod. The onset of meiosis in the male begins at puberty.Spermatogenesis continues throughout (the reproductive) life.When the complexity of sexual development and female andmale gametogenesis is considered, it becomes apparent that preand postnatal drug exposure is a special toxicological problem having different outcomes. The specificity of the male and femaledevelopmental processes also accounts for unique reactions totoxic agents, such as drugs, in both sexes.After fertilization of the oocyte by one of the spermatozoa in theoviduct, there is the stage of cell divisions and transport of the blastocyst into the endocrine-prepared uterine cavity. After implantation,the bilaminar stage is formed and embryogenesis starts. The next7 weeks are a period of finely balanced cellular events, including proliferation, migration, association and differentiation, and programmedcell death, precisely arranged to produce tissues and organs from thegenetic information present in each conceptus. During this period oforganogenesis, rapid cell multiplication is the rule. Complex processesof cell migration, pattern formation and the penetration of one cellgroup by another characterize the later stages.Final morphological and functional development occurs at different times during fetogenesis, and is mostly only completed after birth.Postnatal adaptation characterizes the passage from intra- into extrauterine life with tremendous changes in, for example, circulatory andrespiratory physiology (see also Table 1.1; Miller 2005).1.4Reproductive and developmental toxicologyReproductive toxicology is the subject area dealing with the causes,mechanisms, effects and prevention of disturbances throughout the

71Pregnancyentire reproductive cycle, including fertility induced by chemicals.Teratology (derived from the Greek word τερα which originallymeant star; later meanings were wonder, divine intervention and,finally, terrible vision, magic, inexplicability) is the science concernedwith the birth defects of a structural nature. However, the terminologyis not strict, since literature recognizes also “functional” teratogeniceffects without dysmorphology.Reproductive toxicity represents the harmful effects by agents onthe progeny and/or impairment of male and female reproductivefunctions. Developmental toxicity involves any adverse effect inducedprior to attainment of adult life. It includes the effects induced ormanifested in the embryonic or fetal period, and those induced ormanifested postnatally. Embryo/fetotoxicity involves any toxic effecton the conceptus resulting from prenatal exposure, including thestructural and functional abnormalities of postnatal manifestations ofsuch effects. Teratogenicity is a manifestation of developmental toxicity, representing a particular case of embryo/fetotoxicity, by the induction or the increase of the frequency of structural disorders in theprogeny.The rediscovery of Mendel’s laws about a century ago, and theknowledge that some congenital abnormalities were passed fromparents to children, led to attempts to explain abnormalities in children based on genetic theory. However, Hale (1933) noticed thatpiglets born to sows fed a vitamin A-deficient diet were born without eyes. He concluded that a nutritional deficiency leads to amarked disturbance of the internal factors which control the mechanism of eye development. During a rubella epidemic in 1941, theAustralian ophthalmologist Gregg observed that embryos exposedto the rubella virus often displayed abnormalities, such as cataracts,cardiac defects, deafness and mental retardation (Gregg 1941).Soon after it was discovered that the protozoon Toxoplasma, a unicellular parasite, could induce abnormalities such as hydrocephalyand vision disturbances in the unborn. These observations provedundeniably that the placenta is not an absolute barrier againstexternal influences.Furthermore, in the early 1960s maternal exposure to the mildsedative thalidomide appeared to be causing characteristic reductiondeformities of the limbs, ranging from hypoplasia of one or more digits to the total absence of all limbs. An example of the thalidomideembryopathy is phocomelia: the structures of the hand and feet maybe reduced to a single small digit, or may appear virtually normal butprotrude directly from the trunk, like the flippers of a seal (phoca).This discovery by Lenz (1961) and McBride (1961) independentlyled to a worldwide interest in clinical teratology.Fifty years after the thalidomide disaster, the risk of drug-induceddevelopmental disorders can be better delimited; to date there has1 General commentary on drug therapy and drug risks in pregnancy1.4 Reproductive and developmental toxicology

81.4 Reproductive and developmental toxicologybeen no sudden confrontation by a medicinal product provoking,as in the case of thalidomide, such devastating disorders. Drugsthat nevertheless caused birth defects, such as retinoids, wereknown and expected, base

This book is based on a survey of the literature on drug risks during pregnancy and lactation, as yet unpublished results of recent studies, and current discussions in professional societies dealing with clinical teratology and developmental toxicology. The book reflects accepted