Transcription

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003Applied Management Research: Special ProjectDrivers of Marketing Spending in Motion PicturesProfessor: Dominique HanssensTeam:James Gilbert-RolfeUmaima MerchantVeronika Moroian

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003About the AuthorsJames Gilbert-Rolfe has an MBA from The Anderson School at UCLA (Class of 2003) and aBSBA from Georgetown University. He has held a variety of strategic planning and finance rolesat major companies including Marriott International and Paramount Pictures. He can be contactedat james.gilbert-rolfe.2003@anderson.ucla.edu.Umaima Merchant has an MBA from The Anderson School at UCLA (Class of 2003). She alsoholds a Masters degree in International Marketing from the University of Strathclyde, UK. Sheworked for three years in International Business with a leading Indian pharmaceutical companybefore going on to business school. As of September 2003, Umaima will be a Senior .edu.Veronika Moroian has an MBA from The Anderson School at UCLA (Class of 2003). She alsoholds a degree in Computer Science from Universidad CAECE (Centro de Altos Estudios enCiencias Exactas) of Buenos Aires, Argentina. She worked for eight years at IBM in differentpositions including marketing of software products for different regions in Latin America andsales of e-business solutions for the telecommunications industry. During summer 2003 sheworked at DIRECTV (El Segundo, California) rotating through different positions. She can becontacted at veronika.moroian.2003@anderson.ucla.edu.-2-

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003Table of ContentsEXECUTIVE SUMMARY . 51. ADVERTISING SPENDING IN THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY. 71.1. INTRODUCTION . 71.2. SCOPE OF THIS PAPER . 101.3. RESEARCH METHODOLOGY . 111.3.1. Data Sources . 111.3.2. Interviews. 121.4. STRUCTURE OF THIS PAPER . 132. INDUSTRY REVIEW – THE DOMESTIC THEATRICAL MARKET. 142.1. INTRODUCTION . 142.2. NON-MARKETING AREAS . 142.2.1. Financing, Talent, Production. 152.2.2. Distribution . 162.2.3. Exhibition. 192.2.4. Audience . 202.3. THE MOVIE MARKETING PROCESS . 212.3.1. Budgeting and Planning. 212.3.2. Targeting and Tracking. 222.3.2. Advertising: Pre and Post Release . 223. DRIVERS OF ADVERTISING SPENDING. 253.1. OVERVIEW . 253.2. THE OPENING WEEKEND . 273.2.1. Films Are Highly Perishable. 303.2.2. Theaters Have More Flexibility Than They Used To. 323.2.3. Revenue Sharing Agreements Favor Distributors in Early Weeks. 343.2.4. Box Office Grosses affect Marketability in Future Revenue Windows . 343.2.5. Early Box Office Results may be a Signal of Quality to Consumers . 353.3. INSTITUTIONAL AND CULTURAL FACTORS . 363.3.1. Risk-Aversion and Corporate Inertia . 363.3.2. Talent Compensation . 383.5. CHANGES IN MEDIA DYNAMICS . 393.5.1. Increase in Media Costs . 393.5.2. Decrease in Media Reach. 40-3-

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 20034. CONCLUSION. 424.1. RECOMMENDATIONS . 424.1.1. The Creative Sphere. 424.1.2. The Scheduling and Release Pattern. 454.1.3. The Marketing Effort . 504.2. SUMMARY . 534.3. AREAS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH . 535. BIBLIOGRAPHY. 55Academic Papers. 55Books . 56Websites. 56Magazines . 576. APPENDIXES . 58APPENDIX 1: The Interview Tool. 58APPENDIX 2: Media Budget to Box Office Total . 62APPENDIX 3: Other Forms of Media used in Advertising a Film . 63APPENDIX 4: Ancillary Revenue Streams. 65APPENDIX 5: Sawhney and Eliashberg . 69APPENDIX 6: Opening Weekend on Box Office Gross. 71APPENDIX 7: Negative Cost on Box Office Gross. 72APPENDIX 8: Top 20 Highest Grossing Films of all Time . 73APPENDIX 9: Presence of a Star on Box Office Gross. 74APPENDIX 10: Presence of a Star on Negative Cost . 75APPENDIX 11: Presence of a Star on Media Budget . 76APPENDIX 12: Multiple Regressions . 77APPENDIX 13: Example of Released Dates and Changes Announcement. 78-4-

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003EXECUTIVE SUMMARYThis paper studies the apparent trend of accelerating marketing expenditure in the motion pictureindustry. While the number of movies released during the past decade has remained roughlyconstant, relative marketing costs per movie have increased significantly. Much more money isbeing spent in real terms to market each film, with no proportional increase in box office return.Our purpose in this paper is to identify the drivers of this unusual growth in advertising spending,using three different sources to inform our analysis: actual motion picture performance data, firsthand interviews with industry insiders, and existing academic literature related to this subject.Based on our research we have identified ten “drivers” of marketing spending, each of whichrelates to one of three major themes: 1) the narrow industry focus on opening weekendperformance as the ultimate measure of success or failure of a movie; 2) the nature of the culturaland organizational environment within individual studios and the industry overall; and 3) theincreased “cost of awareness” driven by television advertising price inflation and the decreasedreach of the media networks. Together, the ultimate consequence of these factors is an increase inthe cost of awareness and acceleration in media spending.We believe that the overarching importance of opening weekend performance is caused by anumber of interrelated factors, including the high degree of perishability of feature films, theincreased flexibility of movie theatres, current methods used for revenue sharing betweenexhibitors and distributors, and the importance of the domestic box office grosses as a signal ofboth the quality of the picture and its future marketability in ancillary revenue streams.Within the main studios and the industry as a whole, we observed a culture of organizational riskaversion that compels the studios try to secure the success of a movie by the “proven” methods:star power and sequels, accompanied by huge marketing budgets and pre-released promotions.The mergers and acquisitions experienced by the industry during recent years might beexacerbating this risk averse behavior. Moreover, the significant power of major creative talentas well as current compensation structures create incentives for stars of all kinds to lobby to raisemarketing expenditures.-5-

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003Finally, in the last case, we observed a consistent increase in the television ad spot costs duringrecent years, as well as a decrease in the reach of this medium as a consequence of theproliferation of television channels.After looking at each of these drivers of spending, we classified them into two categories: thosethat cannot be mitigated by a single studio acting unilaterally, and those that could be addressedwithout coordinated industry action. In our conclusion, we recommend that the studiosconcentrate their attention on the actionable drivers in order to control and, if possible, decreasetheir relative marketing spending.-6-

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 20031. ADVERTISING SPENDING IN THE ENTERTAINMENT INDUSTRY1.1. IntroductionThe entertainment industry, and Hollywood in particular, touches the lives of people all over theworld. Across boundaries of time and culture, popular images of the movie business holdpeople’s fascination: glamorous stars, extravagant premieres, visionary directors, mercurialproducers the list goes on. But above and beyond its iconic status across the globe, the UnitedStates entertainment sector, and movies in particular, also remain a huge and important industrydomestically and overseas.Motion pictures are complex products, and remain very difficult to produce, market, and makemoney from. They are an experience good, meaning the success of a product can only bedetermined after launch and adoption: the public doesn’t know that it likes a movie until it sees it,and producers don’t know if it will succeed until the public decides. Further, with a “shelf life” ofonly a few weeks, most movies have only a week or two to capture the audience’s imaginationbefore they are lost amid the constant onrush of new offerings. Only a handful of pictures enjoylong runs and become profitable in their first release, while most movies released theatrically losemoney.While the movie industry is thus fraught with risk, the professionals who make their living takingthe chances nevertheless do their best to minimize it. By making strategic choices in bookingtheatres, budgeting, and hiring producers, directors and actors with marquee value, studios try toposition a movie to improve its chances of success.Thus, using judgment and expertise, the large movie studios routinely gamble hundreds ofmillions of dollars every year in producing big budget films that each may or may not ignite thebox office. Each film is a carefully crafted product, and care is taken to ensure that it has theelements that can reliably translate into box office success – usually some combination ofpowerful concept, appealing storyline, major stars, and technical wizardry, all backed up by a-7-

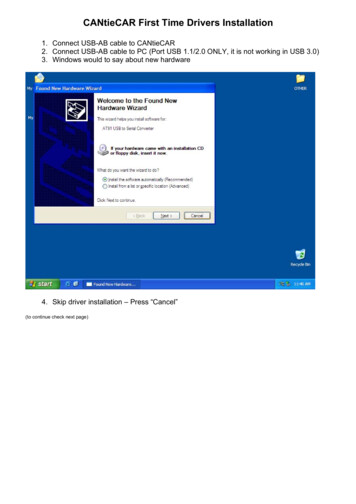

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003strong marketing campaign. Sometimes it works, as in the case of Spiderman, which had a verystrong, familiar concept, or Signs, which reaped the “star-power” of its director, M. NightShyamalan, and star, Mel Gibson. When the combinations work, they translate into tens orhundreds of millions of dollars of box office revenue for their owners, and, just as importantly,additional millions in ancillary revenue streams such as home video, television and internationalmarkets.But sometimes even the best laid plans for the most (apparently) well-packaged movies can fail.Waterworld, for instance, had a strong concept, an actor at the peak of his career (Kevin Costner)and a huge production budget, yet the movie was completely rejected by audiences worldwide.In contrast, Home Alone, which had a much smaller budget and no real stars, remains one of thebest selling movies of all time.In this complex and unpredictable industry environment, where all product decisions areinterrelated, and so many one-time, situation-specific choices can make or break a title’s success,one very interesting aggregate (and so far unexplained) behavioral trend has become apparent inthe recent years. This trend is the apparent acceleration of marketing expenditure at rates aboveand beyond growth in the return from that expense (i.e., gross box office). This observation is thecentral theme we will investigate in our paper.600 35500 30 25400 20300 15200 10100 50 0Avg. Marketing ( MM)# of Films ReleasedFigure 1.1 - Pictures Released vs. MarketingSpending1991 1992 1993 1994 1995 1996 1997 1998 1999 2000 2001# Films ReleasedAvg. Mkt'g Spend / FilmNote: Figures are in inflation-adjusted (2002) dollars-8-Source: MPAA

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003Figure 1.1 clearly shows that even as the number of movies released during the past decade hasremained relatively flat, average marketing spending in terms of print and advertising costs permovie has increased significantly. Clearly, the film industry in aggregate is spending much moremoney in real terms to market each film. Using different data, Figure 1.2 further suggests that thisobservation might be cause for alarm. It shows how the average ratios of marketing expense toboth production budget and gross box office revenue have increased between 1993 and 2000.Figure 1.2 - Relative Increase in Media SpendingMedia as % of Prod. Budget & Box 97199819992000Av erage Ratio of Media/Prod. BudgetSource: Proprietary 875-title databaseAv erage of Ratio of Media/Box OfficeWhile the level of media spending does have a positive effect on box office revenues, regressionanalysis we performed also indicates that it still only explains less than half of the variation inbox office “take” (Appendix 2). From the charts above, we can see that recent years’ increasedincremental media spending on each movie is clearly not buying a proportionate amount ofrevenue: between 1991 and 2001, while industry revenues increased 75%, marketing expensegrew a whopping 157%! Figure 1.3 shows this effect in another way over the period 1999-2001.-9-

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003Figure 1.3 - Box Office Revenue per Marketing DollarRevenue Per Marketing 3.72 3.80 3.65 3.60 3.40 3.12 3.20 3.00 2.80199920002001Source: MPAAThe obvious implications of these observations for profitability are clear: increases in marketingexpenditure come out of the bottom line, meaning lower final returns when these increases are notcommensurate with increases in revenue. While exact details about picture profitability are verydifficult to calculate because major studios report aggregate financials as part of large mediaconglomerates, and individual movie profit structures are usually unique and very rarelypublished, anecdotal evidence from industry insiders does indicate that this increasingexpenditure is squeezing studio margins. Unchecked, ever-larger marketing expenditures willonly worsen this burgeoning problem.All this raises the following important questions: are marketing professionals in the film industrysimply misguided in continuing to spend more and more on media, or is their behavior rational?Are studios engaged in an arms race of marketing spending? What is driving this trend, and whatcan be done about it?1.2. Scope of this paperThis paper proposes to identify and study the industry issues (“drivers”) that are fueling the largertrend of disproportionate marketing expense growth. In this we have focused on advertisingexpenditures directly related to major studio domestic theatrical releases (i.e., within the UnitedStates and Canada).- 10 -

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003While we recognize the importance to studios of ancillary revenue streams from home videoreleases, pay-per-view, television syndication, and international theatrical markets, marketingactivity for each of these streams is generally managed independently. We have in any case,while trying to limit the focus of the paper, nevertheless also considered these other outletsqualitatively, since theatrical release does impact their ultimate performance.1.3. Research MethodologyOur research was based on a combination of data collection and analysis, and first handinterviews.1.3.1. Data SourcesIn addition to academic publications, periodicals, and survey sources, we studied an extensivedatabase of over 875 movies released in the U.S. between 1993 and 2001, as well as a moredetailed subset of it, representing 331 pictures over the period 1995 to 1998. Individual titleinformation included in the database was compiled from various sources available in the publicdomain, including industry periodicals, websites such as IMDB.com, and fee-based data services.Industry historical information was taken from the MPAA (Motion Picture Association ofAmerica) database, and other industry sources such as NATO (National Association of TheatreOwners).Our research focused on the behavior of the following studios: Universal Pictures The Walt Disney Co. / Buena Vista / Miramax Warner Bros. / New Line Cinema Sony Pictures Entertainment / Revolution Studios / Columbia DreamWorks SKG Paramount Pictures Twentieth Century Fox Metro Goldwyn Mayer (MGM)- 11 -

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003We can see in the following chart (Figure 1.4) that these studios undertake the majority ofindustry ad spending. These top studios also account for more than 90% of industry revenues. Wethus believe that our research, while not examining in detail the marketing behavior ofindependent or specialist studios, distributors, and exhibitors, is properly focused on the mostsignificant portion of the industry.Figure 1.4 - Major S tudio spending vs Total Industry Ad Spending3,000 0001999Industry Ad Spending2000Major Studio spending2001Source: Hollywood Reporter, 5/14/20021.3.2. InterviewsWe conducted a series of interviews with more than fifteen industry participants and academicprofessionals specializing in the entertainment and/or marketing areas, and ranging in perspectivefrom small independent film producer to studio head. The majority of the interviewees werestudio executives at or around the vice-president level, and directly involved in the distributionand promotion of films. All interviews were conducted using an interview instrument designedbroadly to investigate the following principal questions:1) How are film marketing budgets and advertising/promotional strategies planned?2) What is the effect of competition on marketing spending?3) What are the main drivers of escalating marketing expenditures?- 12 -

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003Given the breadth of different interviewees’ professional experience and functional concentration,specific, individual questions were sometimes tailored to ensure relevance for a particularrespondent. A copy of the generic questionnaire is included in Appendix 1.1.4. Structure of this paperThis paper is divided into four main sections as follows, plus supplementary appendices:1) Introduction2) Industry Review: This section very briefly describes the various stakeholders in themotion picture business as they are related to marketing decisions. It also covers mainissues and concepts involved in the process of marketing a typical studio film.3) Drivers of Advertising Spending: This section covers the main output of this project,analyzing what we believe to be the drivers of escalating marketing spending.4) Supplementary Analysis and Salient Research: We conducted a survey of selectacademic studies on the motion picture industry and found some interesting results thatwe believe are important for managers and decision makers in this industry to be awareof. We explore some of these ideas and provide relevant analysis of our own dataset.We should mention here that in order to keep this paper at a readable length and to maintain asmooth narrative structure, we have appended several interesting discussions and a variety ofadditional background information to the end of the main paper. In particular, other than back updata, these Appendices contain a summary of a very important piece of academic researchrelevant to this work, namely the “Parsimonious Model for Forecasting Box Office Revenues” bySawhney and Eliashberg (1996) (Appendix 5).- 13 -

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 20032. INDUSTRY REVIEW – THE DOMESTIC THEATRICAL MARKET2.1. IntroductionIn trying to understand the drivers of marketing spending in the movie business, it is important tohave a rudimentary knowledge of key industry dynamics, and of film promotion and advertisingin particular. This section seeks to provide that understanding to the uninitiated by explaining therelevant interests of other stakeholder groups at different points in the motion picture value chain,as well as looking at the stages of, and considerations present in, the development and executionof a typical movie marketing plan.Though more sophisticated readers may already be familiar with most of the following, we arehopeful that this section incorporates fresh observations gleaned from our series of interviews,and may offer some new insights even to those with substantial industry experience.2.2. Non-Marketing AreasWhile our work has been concentrated principally on behavior in the advertising and promotionalarea of the film industry (what we are choosing for the sake of simplicity to call marketing), wewill nevertheless briefly discuss the considerations present in other areas of the business in orderto provide a broader context for understanding marketing-related decision-making. This reflectsthe reality that neither marketing nor any other important decisions are made in a vacuum. In fact,the complicated web of interrelationships between individual industry participants, and amongmajor studios’ various business units usually precludes such independence. Figure 2.1 belowshows how we have chosen to delineate these different functions, and their place in the industryvalue chain.- 14 -

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003Fig 2.1: Getting a Theatrical Feature To bitionAudienceMarketingOf the list of studios considered in this research (described in Section 1.3.1.) all are involved inthe full range of activities up to the point of exhibition, either via internal company divisions,affiliated companies or both. Wherever appropriate, any reference to a “major studio” is meant toinclude all such subsidiaries and affiliates.2.2.1. Financing, Talent, ProductionThis category of activities is clearly the broadest, encompassing the work of all participantsleading up to the point of having a completed film “in the can”, from the heads of mediaconglomerates to individual craftspeople, talent agents, and artists. As noted by Vogel (2001),these various parties act together in a fluid, “contract-driven” environment to make the films thatdistributor/marketers, through their own complex network of agreements with both exhibitors andfilmed-property owners, bring to market. While we will not attempt to elaborate on the manyways that “concepts”, talent, and financing are joined together in making a film, we will discusstwo strategic issues that, through these participants, affect the marketing function: productionbudget and “star power.”Major-studio executives financing and producing a slate of films are working within anenvironment in which gross revenues are the primary public measure of financial success. Theyare also strikingly dependent on the top-grossing few films in any given year (see Figure 2.2below). Executives are thus naturally concentrated on trying to enhance and secure revenues foreach title, and for their most promising “tent-pole” productions in particular. Two maininvestments are believed to make this possible: production value and stars.- 15 -

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003Figure 2.2 - Revenue Concentration By Studio, 2002Percent of Total100%3128312212192479Total # of FilmsReleased byStudio, 200280%Top Mov ie60%#2 Mov ie40%#3 Mov ie#4 Mov ie20%All OthersThis graph shows shares of 2002 total studio gross revenue contributedby 100MM pictures. No studio had more than four such hits in 2002.GMMSonyPicturesBuenaVist tDreamworks0%Source: Hollywood ReporterNot surprisingly, many studios and academics conclude that the production budget is highlycorrelated with revenues. A second preferred means of enhancing (and securing) revenues is thepresence of a popular star in the production. Such major stars, whether in front of or behind thecamera, can also often drive up marketing expense, in addition to commanding a large chunk ofthe production budget. Several studies have been conducted to test both these perceptions. Wediscuss these in Section 4.2.2.2. DistributionDistribution decisions (relating to when and where to show movies) are, of course, very closelyconnected to and coordinated with what we have already described as the marketing activities thatare the focus of our paper -- the main advertising and promotional activities explicitly aimed atconsumers.- 16 -

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003“ A very serious game of strategy is at work – a cross between chess and chicken – whichstudio distribution chiefs play year round, but with increasing intensity during the summer andholiday release period.” (The New York Times, December 6, 1999)The decision of when to release a particular film is a very important one. Nowadays, almost allfilms are released on a Friday, giving literal meaning to the term “opening weekend”. Thestrategic question for distributors therefore is to decide on which weekend to release. Ourresearch showed that while there is a high degree of variability in box office performance fromweek-to-week within a given year, there is relatively much less variability between the sameweekend in different years. This predictable weekly seasonality (Figure 2.3 below) means thatdistributors’ release schedules are based on very similar assumptions about total market size foreach weekend, leading to a dynamic competition in which studios strategically position theirpictures on release dates to try and maximize their market share and revenue versus competitorsdoing the same. 120,000 30,000 100,000 25,000 80,000 20,000 60,000 15,000 40,000 10,000 20,000 5,000 0Marketing - US 000'sProduction and Box Office - US 000'sFigure 2.3 - Weekly Seasonality, 1993 to 2001 0113253749Week of the YearAverage Box OfficeAverage Prod. BudgetAverage Media Spend- 17 -Source: Team's 875-Title Database

The Anderson School at UCLAFall 2002 / Winter 2003Typically, very rich weekends (e.g., Memorial Day, July 4th, and Christmas) attract the highestpotential (and budget) film titles, and a corresponding marketing effort. With a limited number of“big” weekends to go around, the scheduling game for similar major-release titles can become agame of chicken played out in the industry press. Even in such an environment, there remainopportunities on the margins: films targeted well outside of a blockbuster’s demographic can stillsucceed in spite of the presence of the 800-pound gorilla in the weekend.Almost as important as the timing of the release is i

at james.gilbert-rolfe.2003@anderson.ucla.edu. Umaima Merchant has an MBA from The Anderson School at UCLA (Class of 2003). She also holds a Masters degree in International Marketing from the University of Strathclyde, UK. She worked for three years in Internatio