Transcription

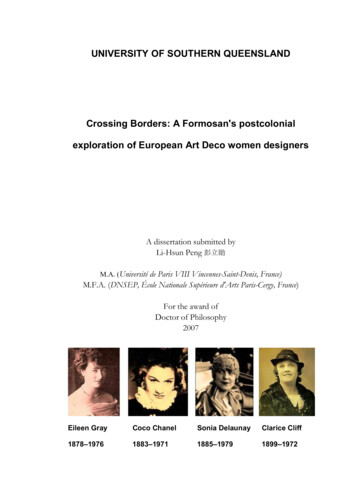

UNIVERSITY OF SOUTHERN QUEENSLANDCrossing Borders: A Formosan's postcolonialexploration of European Art Deco women designersA dissertation submitted byLi-Hsun Peng 彭立勛M.A. (Université de Paris VIII Vincennes-Saint-Denis, France)M.F.A. (DNSEP, École Nationale Supérieure d'Arts Paris-Cergy, France)For the award ofDoctor of Philosophy2007Eileen GrayCoco ChanelSonia DelaunayClarice Cliff1878–19761883–19711885–19791899–1972

Li-Hsun PENGAbstractThis is research on cultural identity and the history of design. The project, byapplying aspects of postcolonial theories (third space, border theory and hybridity)to the history of the four women designers in the Art Deco period in Europe,explores the influences of Eastern cultures in developing their Western designperspective.Their experience in fighting against patriarchal society toward success is a usefulanalogy for my country Taiwan’s struggle to win recognition in the world. It isthrough the recognition of these four women designers’ contributions to designhistory that I present their stories as models to my design students in Taiwan toassist them in establishing their own design identity.The research findings indicate that these women designers’ benefited fromEastern culture and created a successful cultural mélange between the East andWest. Similarly, my design students in Taiwan will have the opportunity toreverse the pathway in appropriating from the West to create new possibilities inthe East. I argue that hybridity is a key component for responding to and foraddressing the identity crisis and internal disruption in present-day Taiwan.Through knowing and understanding these women designers’ achievements,Taiwanese students have a model for self-reflection to recognise the importanceof our own cultural value to the world.ii

Li-Hsun PENGiii

Li-Hsun PENGAcknowledgementsI would, firstly, like to thank my supervisor, Associate Professor Dr RobynStewart for her unfailing support, intelligence and patience throughout mycandidature. With her supervision and encouragement, I discovered and startedmy postcolonial exploration across my own identity and the four womendesigners in the Art Deco period. Secondly, I also owe gratitude to my associatesupervisor, Senior Lecturer Dr Janet McDonald, for her unconditional supportand effective guidance in my dissertation structure and methodology.I give thanks to my country, Taiwan, and to our Government, for providing mewith the opportunity for this research, an undertaking through a two-year fullscholarship award from the Ministry of Education, Taiwan. Many thanks toAssociate Professor Dr Laurent and Dr. Pauline Weng, Associate Professor WenKuang Huang, Associate Professor Pedro & Daisy Tsai, Associate ProfessorKathy Kou, Assistant Professor Dr Chien-Wen Chen, Assistant Professor DrHong-Sheng Chen, and all my friends for their warm support and also mycolleagues in the Ling Tung University. With their friendship and administrationhelp, my research and study in Australia has become possible.This thesis has been edited. I would like to thank my editor, Tony Roberts, forthe quality and effort he has contributed to my dissertation. Tony is a senioreditor who specialises in linguistic and I.T. fields.iv

Li-Hsun PENGFinally, my greatest debt of gratitude and love is to my charming wife CarolineJeng-Jia Lou; without her constant and mutual support, I would not haveaccomplished my study. I owe profound thanks to my parents, Ms. Tsue-Une Laiand Dr. Tsu-Hsin Peng, both for their encouragement and because my researchand exploration is a part of their life-long experiences. Finally, I want to give aspecial thank-you to my whole family, Professor Thomas & Hsio-Ying Hlawatsch,Dr. Richard and Cathy Peng, Hsio-Yu and Jacob Wang, Diana and Jackson Lou,Stephan Hlawatsch, Hannah Wang, Laura Lou and also many other relatives.With their blessings and help, this research has become meaningful.v

Li-Hsun PENGContentsAbstractiiCertification of DissertationiiiAcknowledgementsivContentsviList of FiguresxiPrologue1Chapter 1Description of the study31.0Introduction31.1Methodology:71.1.1 Historiography71.1.2 Bricolage as methodology91.2Background to the problem121.3Statement of problem and limitation of the study141.4Rationale and significance of the study151.5Proposed outcomes of the study171.6Commencing a third space narration171.6.1 Oral history on the shifting spacesvi

Li-Hsun PENGexperiences in my family191.6.2 The nature of Formosan culture28Chapter 2Crossing borders2.032The cultural scene in Europe before the end ofthe First World lopment362.1.1 Development of Art Deco392.1.2 Challenging patriarchal barriers442.1.3 The impact of the Great Depression472.1.4 Art Deco and the Great Depression492.1.5 Women in the Arts: Gender identities532.1.6 Postcolonial theory: colonialism andpostcolonialism55Chapter 3Art Deco and Exhibitions3.172Art Deco movements: the background, causes,influences and outcomes723.1.1 Historical colonisation73vii

Li-Hsun PENG3.1.2 Colonial and empire exhibitionsand their influence3.23.374Connecting myself with colonial andempire exhibitions87Orientalism on display933.3.193Utopia book of FormosaChapter 4The analysis984.1Domestic and utilitarian concern984.1.1 Personal experiences and border explorations984.1.2 Comparing Eileen Gray and Clarice Cliff’s domesticexperience4.1.3 Hybridity and my domestic experience1061104.1.4 Establishing Taiwan’s third space Identityfrom our history1144.1.5 The four women Designers and third space experience 1234.2Gender issues1404.2.1 Comparing the four women designers’ border140experiences from a gendered perspecti384.2.2 The gendered social environments of Gray, Chanel,and Cliff4.3157Appropriation1674.3.1 Appropriation and my third space experiences167viii

Li-Hsun PENG4.3.2 Cultural appropriation and these four women169designers in Art Deco4.44.3.3 Gray, Delaunay and Cliff appropriated from De Stijl1804.3.4 Appropriation and hybridity185Issues of exoticism1994.4.1 Multi-culturalism and exoticism in Paris1994.4.2 Hybridity into Exotic style among the four womendesigners4.4.3 Using hybridity to become a successful brand name201223Chapter 5Conclusion, making alliances with "Colonisers"2305.1 Significance of the study: Women designerssuccess and appropriation of Orientalism2305.1.1 The inspiration of Eileen Gray's story2315.1.2 The inspiration of Coco Chanel's story2355.1.3 The inspiration of Sonia Delaunay's story2395.1.4 The inspiration of Clarice Cliff's story2425.1.5 Women designers did appropriatefrom the East and from Orientalism5.2245My appropriation of concepts from the West2465.2.1 Lessons from the Exhibitions concerning Taiwan2485.2.2 The importance of regaining cultural autonomyix

Li-Hsun PENGand self-respect for Taiwanese2495.2.3 Hybridity of different cultures andraces merging together5.3Fine art and design – a Taiwanese perspective2522545.3.1 Cultural identity for my students in Taiwan:when the West meets the East5.4254Key future directions for this research2555.4.1 Posting my ideas online and the copyright issues2555.4.2 A research website should include the following255Notes257References260Web site and newspaper references:274Bibliography of Images:277x

Li-Hsun PENGList of Figures (See details in Bibliography of Images, page 277)Image 1.1: 1966; George Kerr, Formosa Frontier Island17Image 3.1: 1925; ‘View from the Northwest’, and ‘Night Scene in Grand Palais’80Image 3.2: 1937; ‘Pavillons des colonies: Indochine & Afrique équatoriale’85Image 3.3: 1887; ‘Aborigines from Southern Formosa with their guns’, 1875,‘Savage Man and Woman’Image 3.4: 1884; ‘Formosan Types and Costumes – Butan Captives in Japan’8790Image 3.5: 1935, Taiwan Exhibition held mainly in Taipei with Art Decostyle91Image 3.6: 1935, Taiwan Exhibition showed the Art Deco styleArchitecture92Image 3.7: 1704; George Psalmanazar, ‘An Historical and GeographicalDescription of Formosa’, ‘Figure of Formosans’,94Image 3.8: 1704; George Psalmanazar, ‘The Funeral, or Way of Burning theDead Bodies’96Image 4.1: 1990; my works and exhibition during the stay in Paris103Image 4.2: 1930s; Conical Sugar Sifters and Stamford Teapots109Image 4.3: 1633; ‘Fort Zeelandia built in Tainan’, ‘the IslandFormosa and the Pescadores’117Image 4.4: 1926-29; Functional-oriented design, ‘BedroomDressing table, designed for E-1027’, ‘Kitchen in E-1027’126Image 4.5: 1912; Chanel Hat design for Gabrielle Dorziat130Image 4.6: 1916; Liqueur Poster, 1924, Harlequin Rug design133Image 4.7: 1931; Tennis series and Age of Jazz137Image 4.8: 1926–29; ‘aerial views of E-1027140xi

Li-Hsun PENGImage 4.9: ‘Le Corbusier letter to Eileen Gray regarding E-1027’146Image 4.10: 1925; Chanel’s prototype of ‘Little Black Dress’,Chanel’s ‘Black Lady’ in Vogue152Image 4.11: 1938; Le Corbusier, ‘Three Women (Graffite à Cap Martin)’160Image 4.12: 1990; My creation of stained glass and installation painting167Image 4.13: 1911; the first abstract design work, cover designfor Ricciotto Canudor176Image 4.14: 1926-29; ‘Plan for E-1027’, Roquebrune Cap Martin,1926c Architect’s Cabinet180Image 4.15: 1926-28; ‘Costume design for Carnival in Rio’182Image 4.16: 1922; ‘Cette Eternel Femme’, 1926, ‘Le Petit Parigot’191Image 4.17: 1989; My stained glass restoration and creation200Image 4.18: 1913; Eileen Gray, ‘Le Destin Screen and Pirogue Sofa’204Image 4.19: 1920s; Chanel ‘Faux Bijou’, ‘Chanel Exotic Styles’206Image 4.20: 1924; ‘Chanel designed costumes for Diaghilev and Le Train Bleu’208Image 4.21: 1913 Details of Bal Bullier and Sonia Delaunay wearing hersimultaneous dressImage 4.22: 1918; ‘Costume Cléopâtre’, 1917, ‘Costume Aida Madrid’214216Image 4.23: 1928; Bizarre Ware Advertising, and Bizarre shop girls atWorkImage 4.24: 1934-1939; Clarice Cliff, Plaques design218220Image 4.25: 1924; Arab Figure & Miniature Vases, 1929, Fantasque Teapot 221Image 4.26: 1920-23; Chanel Perfume No. 5, 2005, ‘a revised bottle ofChanel No. 5’224Image 4.27: 1932; Chanel Jewellery226Image 5.1: 1920-30; Furniture and tables made by Eileen Gray232xii

Li-Hsun PENGImage 5.2: 1920s; Chanel Style of Les Années 20, the basic elementsin her costume design236Image 5.3: 1925-28; Sonia Delaunay’s fashion design with inspirationsfrom many styles241Image 5.4: 2001; Exhibition in Glasgow Museum, 2001,Christie’s Clarice Cliff auction243xiii

PrologueIt was on 5 December 2004, I arrived at Brisbane Airport in the earlymorning from Toowoomba; I had my confirmed-return tickets from my previousflight five months ago and was about to take the Royal Brunei Airlines to Brunei,then back to Taiwan to meet my family. A few months before, I had had apleasant trip from Taipei with a two day stopover in Brunei. I found it was asmall but charming Islamic state full of exotic colours. So I was looking forwardto take this return trip. However, this journey was beyond my expectation andimagination. When I arrived at the Royal Brunei’s counter, the attendant told methat my connected route back to Taipei was cancelled three months ago owing toairline finances; they apologised for being unable to contact me. They said theyhad arranged an alternative route for me; but I would have to fly from Brunei toHong Kong then change to Taipei. This change forced me to stay in Brunei fortwo consecutive nights. They made the reservation of a hotel room for me andtold me everything was well arranged and not to worry about it.When my flight arrived at Brunei Darussalam Airport it was late on aSunday afternoon; the Custom officers stopped me and told me that I was notentitled to obtain an arrival visa because I am from China. I told them that I amfrom Taiwan and that even though my passport is written ‘Republic of China’ itmeans from Taiwan. Mainland China is the ‘People’s Republic of China’. Theypretended not to understand my English. As a result they put me into thedetention centre located inside the airport. Everything happened suddenly andbeyond my control. My status was simply because a Taiwanese citizen becomes‘other’ to them; I had lost my own identity and was trapped in a political struggle.

Li-Hsun PENGMy freedom was limited to staying in the international zone that includedfive small duty-free shops inside the airport; and a small, dark, windowless roomthat they provided for me. This limited zone in the airport was the third space forme; I was misplaced between the two destinations and had become a neutralperson who was losing his identity.As Bhabha argues, “by exploring this third space, we may elude thepolitics of polarity and emerge as the others of our selves” (1994: 39). Throughthis incident, I saw the power authority had over me. However, while standingwithin the third space, I realised that this borderland was in fact a place of refugefor me. It was a space to escape all kinds of political disruptions and to find innerpeace of self. I had therefore transformed as ‘other’ and had established a neutralposition for myself. Thinking about this point, I realised that my personalsuffrage was merely a small matter. Compared to people searching for identities, Iwas still lucky to have decent treatment. My adventure was similar to TomHanks’ character in the film The Terminal. I stayed in this third space merry-goround for two nights until my next flight on Tuesday morning.My stay at Brunei Airport enhanced my determination; it not only helpedto complete my research but it also increased my understanding of the issues ofborder crossing and the third space. It was at that moment I started to realiseTaiwan’s status in the world community.It also strengthened my will andmotivation for researching across the borders of postcolonialism through mypersonal experiences.2

Chapter 1Description of the study1.0IntroductionThe four women designers selected for this study are Eileen Gray (1878–1976), Coco Chanel (1885–1979), Sonia Delaunay (1883–1971) and Clarice Cliff(1899–1972). This study will examine the social contexts of these four womendesigners in the Art Deco period in Europe. It will investigate and analyse theirworks and their accomplishments using my personal experiences as a culturalamalgam of East and West and referencing theories that include border theory,third space identity, and hybridity in the context of the times.Art Deco was also named as the Style Moderne or Modernistic movement inthe fields of applied art, design and architecture. Originating in 1910, this styledeveloped into a decorative style in Europe and the United States during the1920s and 1930s. Held in Paris in 1925, the “Exposition Internationale des ArtsDécoratifs et Industriels Modernes” marked the high point of the Art Deco Movement(“Art Deco”, britannica.com). The Art Deco style symbolised modernismdirected towards everyday design works and applied art objects. Its productsincluded both luxury design items with brand names and design objects in massproduction. The primary motivation was to create high standard design worksand anti-traditional elegance that symbolised wealth and sophistication. This stylehad ended by the beginning of the Second World War (Benton, 2003; Bouillon,1989).Through my interest in the Movement of Art Deco period from 1925 to1939, I realised that despite many books describing Art Deco, little information

Li-Hsun PENGcould be found on women designers’ contributions and on their works. Iwondered whether women designers were purposely left out of the historicalaccounts, as Richardson suggests, “When feminists searched the history booksthey found that women were still largely ‘hidden from history’” (Richardson &Robinson, 1993: 304).My selection of the female designers of Art Deco was triggered by readingabout the 1925’s l’Exposition Internationale Des Arts Décoratifs et Industriels Modernes,an International Exposition held in Paris. That was the first event of the ArtDeco movement.When I read through the documents I had collected on this event, I foundout there were mostly male artists represented throughout the Art Decoexposition. I wondered whether women artists and designers had been excludedfrom this historical event. My research and findings indicate that my scepticismwas correct. Women artists and designers were ‘ignored’ at this occurrence(Lugones & Spelman, 1995; Pollock, 1996; Rowlands, 2002; Terlouw, 1994;Waller, 1991). I speculated this could have been caused by the male dominatedsociety in which women were marginalised through social injustices and unequalsocial systems. Further research indicated that there were four particular womendesigners who were neglected or had had various aspects of their contributionsconcealed from history at this time (1925-1939). Among them, there were: EileenGray, designer and architect; Coco Chanel, fashion designer and entrepreneuse;Sonia Delaunay, fashion designer and colourist; and Clarice Cliff, ceramist. Thisstudy has brought them all together for the first time in the history of design toform a selected representative background of women designers struggling foridentity through their creations. As Slatkin puts it:2

Li-Hsun PENGIn 1973 Linda Nochlin published an essay: Why Have There Been No GreatWomen Artists? that the study of Women Artists was not worthy ofattention because there had been no ‘great’ women artists whose workswere of the ‘quality’ which would merit scholarly attention. Since then,during the past 25 years, an enormous outpouring of convincing andcompelling scholarship has been published (2001: 1).I argue that, historically, the neglect of the women artists and thedesigners’ importance was caused by the patriarchal society in Europe or moreimportantly, the patriarchy was imbedded in art history. According to LindaNochlin (Slatkin, 2001), prior to 1973, art historians did not make any effort todiscover if there were any quality women artists’ who contributed to history of artand design. I would suggest that women artists and designers were simplyignored and hence neglected by the society of their time. Although these womendesigners were named by historians as the women pioneers of modernism (Cox,2001: 54; Fausch, 1994: 120; Rendell, 1999: 228, Wosk, 2002: 148), this researchintends to reveal the fact that their contribution in Europe in the 1920s and1930s was neglected in the history of design.It is apparent that these women designers overcame many difficulties tostart their own design practices. The significance of their creative value and socialachievements as leaders in the early decades of the 20th century (Adam, 1987;Albritton, 1997; Charles-Roux, 1981; Zilkowski, 1998) is the cultural focus of myresearch. As Conway puts it, “Art historians have retrieved many women artistsfrom obscurity and design historians are beginning to do the same for womendesigners”(1987: 63). This research and the analysis of the four women designers’achievements intends to counteract the silences and gender issues that continueto be evident in design history.3

Li-Hsun PENGI believe these four women designers were suffered from colonialism, so,the use of gender issues and postcolonial theories, together with my personalexperience in analysing their achievements, has particular relevance to this study.Taiwan has been successively colonised by the Ming Dynasty, Holland, Spain, theTaywan kingdom, the Manchu Dynasty and Japan (Ching, 2001). As a nativeTaiwanese, I have been trying to understand and compare the different notionsof being colonised and inheriting a cultural heritage that reflected thosecolonisations. The long history of the colonisation in Taiwan underpins myinterest in exploring postcolonial theories (especially border theory, hybridity andthe third space) as a way to analyse relevant aspects of Eastern and Westernsocieties between the First World War and the Second World War (1918–1939).Watson (2001: 246) informs us that the term postcolonial was used “todescribe a global ‘condition’ or shift in the cultural, political and economicarrangements” that followed after the European countries had departed theircolonies. Similarly, I have experienced the disruptions caused by colonisation, yetthe long existence of these foreign cultures in my country has merged into oureveryday life and now also forms part of my cultural heritage.Homi K. Bhabha’s postcolonial theory and the concept of hybridity in theculture of the Third World (Bhabha, 1990b: 57) can be used to describe andsituate my cultural background and personal viewpoint as well as those of thesefour women designers. In 1986, as a person brought up in a country which wasnot internationally recognised, I had little confidence in myself when starting mypostgraduate study in metropolitan Paris. There were many times when I had toadapt and reposition myself through history and language-learning to a brandnew life in a colonising nation. This experience made me later understand and4

Li-Hsun PENGhave empathy with less privileged people in their social contexts, such as thesefour women designers.By identifying myself as a cultural hybrid, this research will focus on themerging of divergent cultures during the Art Deco period in Europe,underpinned by my retrospective accounts of the transition of my own identity.It is through the merging of these divergent cultural experiences that I will bebetter placed to recognise and analyse how these four women designers werepositioned under the cultural influences from the East and West.1.1MethodologyThe primary research method to be used for this study is historiographywith bricolage as my secondary methodology.1.1.1 HistoriographyI include historiography as part of my research methodologies in theattempt to rediscover these four women designers’ details and contributionsin the history of art and design. Bentley (1998: vii) maintains that “at its highestlevel of originality, a historiographical statement may attempt an enquiry whichformer generations would have been happier to call the ‘philosophy of history’ inan applied form”.My interpretation of Bentley’s arguments is that he has identified a dualdescription of historiography. The first application is using historiography asphilosophical research, employing it for practical and relevant uses. The secondapplication is just like deep ploughing into the soil, to uncover from past history;recovering special events, particularly contributions or neglected facts.Historiography can have implications with its effects on the present and thefuture. As Postan says:5

Li-Hsun PENGExcept for Marxists and most historians writing about the philosophy ofhistory, the majority of the philosophers concerned with the methodology ofhistorical and social study — and even some influential social anthropologists— have in recent years ranged themselves against the supposed fallacies of‘scientism’. They accept, however unconsciously, the idealistic dichotomy of‘physical’ and ‘humanistic’ studies of that of pure and practical reason, andconsequently decry all attempts to use the methods of natural science in thestudy of history or of human affairs in general (1971: ix).I believe that researching these women designers’ histories is not only astudy of human affairs but also a recovery of their contributions to breakthrough the barrier of apparent inequality between men and womenpractitioners today. Given that I have conducted my research on these fourwomen designers, an important sector in this study is a discussion on thesignificant changes to the social structure of their time in addition to how theycoped with social injustices.My research using historiography will also investigate these womendesigners’ marginality within their society; they were the very first womendesigners to succeed in the avant-garde period, yet they had not only to deal withtraditional family values but also to create their own social and professionalvalues.By using historiography, I am also recovering and reinterpreting thesefour women designers' histories through the lens of my own identity as aTaiwanese. Bentley states:Historiography teaches blurredness in its constant assertion of culturalinterference and the predominance of standpoint. Once allowhistoriography a role in an understanding of how history fashions itself,6

Li-Hsun PENGtherefore, and complexity comes in through every pore with its contestedassumptions and tortured mentalités (1998: ix).As an educator in the design field, I anticipate that my arguments andfindings through historiography and postcolonial investigation will certainly helpmy Taiwanese students and my society to establish a new aspect in our identityand the positioning of ourselves in the world.1.1.2 Bricolage as methodologyThis research is based on the study of culture. As a bricoleur (Schneider,2001: 167), I will attempt to adopt diverse tasks, collecting and interpreting thepersonal and historical documents on Art Deco design and analysing them. Tocomplement the process of historiography (Bentley, 1998: vii; Jenkins, 1995: 16–19), theoretical sampling (Glaser, 1978: 36), and visual research methods (Banks,2001: 12; Denzin & Lincoln, 2003: 192), I will apply a bricolage process indeconstructing and recuperating the central elements in the works of the womendesigners, reflecting upon these elements and comparing the different categoriesto reveal their creative processes.As Schneider argues, “The term bricoleur is used by Lévi-Strauss to define akind of handyman who invents in the face of specific circumstances, usingwhatever means and materials are available” (2001: 167). I will use a bricolageapproach to my research because this is a structure that allows me to collect datapiece by piece and then assemble and verify the pieces by comparing these fourwomen designer’s social achievements and the creative value of their works.“Society has become a hip-hop culture in the bricolage of cultures, multipleviewpoints, and proliferation of information, continually being recycled andreconfigured into new forms” (Rahn, 2002: 155). Under the bricolage process,7

Li-Hsun PENGdiverse viewpoints may emerge and then be transformed into a new story. Thebricolage process will be comprised of the following qualitative research methodsfor this study.Theoretical samplingTheoretical sampling is a research method component of the bricolage.According to Glaser (1978) that:Theoretical Sampling is the process of data collection for generatingtheory whereby the analyst jointly collects and analyses his data anddecides what data to collect next (1978: 36).The data collection sampling process not only helps me understand theevolution of these women designer’s works, but also by collecting the data I cananalyse the facts emerging as a basis from which to work. An aspect of thisprocess is the need to contextualise the study. A literature survey and analysis ofthe relevant data, using visual and textual information, will be conducted withinthe fields of aesthetics, gender issue and cultural theory. I will explore culturalaesthetic theories within postcolonialism (Griffiths, 1998: 186; Mishar, 1993: 30)and its associated theories of Orientalism (Dudziak, 2003: 153; Said, 1995: 144)and border theory (Billingslea-Brown, 1999: 3) to analyse and clarify howWestern culture adopted aspects of oriental culture as the decoration patternduring the Art Deco period (Benton, 2003; Duncan, 1988; Hillier, 1971).Moreover, as an Asian, the process of establishing meaning and positioningmyself as an intermediate person to carry out this research is an important issue.This will be used to illuminate the process of cultural exchange.8

Li-Hsun PENGCultural comparison and visual analysisThe process of cultural comparison analyses and explains the diversity ofcultural effects in Art Deco and for these four women designers.John Berger argues in his book Ways of Seeing that “we never look just atone thing; we are always looking at the relation between things and ourselves”(Berger, 1972: 9). People’s mental abilities can handle multiple and complicatedthoughts and compare the information or things with our personal experiences toappreciate and discover the value of everything. Comparing and analysing hasthus become part of our ability to make judgements. Banks explains, “All visualforms are socially embedded, and many visual forms that sociologists andanthropologists deal with are multiply embedded” (2001: 79). Since visual formsare usually embedded, using comparison analysis to disengage these connectedforms can help us discover their link in the social context. These visual forms arepart of visual culture. My research on the women Art Deco designers will recoverthe value of the visual culture through comparison analysis research oninvestigating their works.Rose (2001: 6) describes visuality “in which vision is constructed invarious ways: ‘how we see, how we are able, allowed, or made to see, and how wesee this seeing and unseeing therein’”. These ways of observing and seeing existin our everyday lives; different ways of seeing will create value and generatedifferent ideas. Banks (2000: 108) observes that “[G]ood visual research restsupon a judicious reading of both internal and external narratives. At its roots, allvisual objects represent nothing but themselves nothing but theirautonomy”(2001: 12). Through the narrative development of visual research,people can understand more clearly that visual research depends on a goodargument. The visual images are independent; each image therefore carries its9

Li-Hsun PENGown meaning. Harper notes that “visual research depends upon and redistributessocial power” (Denzin & Lincoln, 2003: 192).What Harper means is thatwithout social contexts, visual research will become less meaningful and thus cannot be translated into a new cultural meaning. As Harper argues, “What is thefuture visual sensibility leading an energized social science that isexperimentally ethnographi

5.1.2 The inspiration of Coco Chanel's story 235 5.1.3 The inspiration of Sonia Delaunay's story 239 5.1.4 The inspiration of Clarice Cliff's story 242 5.1.5 Women designers did appropriate fro

![Clinical Biostatistics [CLB]](/img/6/study-guide-clb-2021.jpg)