Transcription

1English Learners in21st-Century Classrooms In her classroom our speculations ranged the world. She breathedcuriosity into us so that each day we came with new questions, new ideas,cupped and shielded in our hands like captured fireflies. When she left us, wewere sad; but the light did not go out. She had written her indelible signatureon our minds. I have had lots of teachers who taught me soon forgotten things;but only a few who created in me a new energy, a new direction.I suppose I am the unwritten manuscript of such a person.What deathless power lies in the hands of such a teacher!—John Steinbeck, recalling his favorite teacher 2M01 PERE5153 06 SE C01.indd 24/13/12 1:59 PM

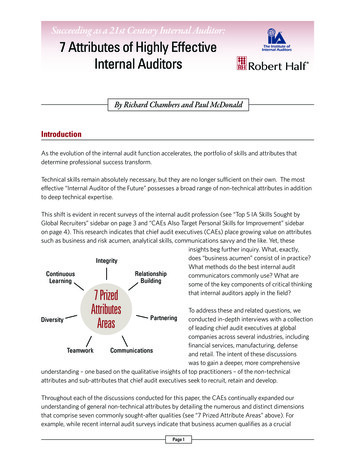

Chapter OverviewGetting to Know ELsTechnology & NewLearning ToolsGetting Basic InformationWhen ELs ArriveInternetClassroom ActivitiesHow Do Cultural DifferencesAffect Teaching & Learning?Definitions of CultureWho Am I in ELs’ Lives?BlogsTeacher as Participant-ObserverWikisSociolinguistic InteractionsPodcastsENGLISH LEARNERSin 21st CenturyClassroomsCultural Responses in ClassesHome Literacy TraditionsPrograms for ELsBilingualEnglish OnlyCurrent Policy TrendsAffecting ELsHigh-Stakes TestingEducation Policy Specific to ELsEasing Newcomers intoClassroom RoutinesSafety & SecurityCreating a Senseof BelongingResearch-Based InstructionIn this chapter, we provide you with basic information on English learners in today’s classrooms,including discussion of demographic changes, legislative demands, and technological innovationsthat impact teachers and students. We address the following questions:1. Who are English learners?2. How can I get to know my English learners when their language and culture are new to me?3. How do cultural differences affect the way my students respond to me and to my efforts toteach them?4. How do current policy trends affect English learners?5. What kinds of programs exist to meet the needs of English learners?6. How are teachers using the Internet and other digital tools to enhance learning in 21stcentury classrooms?Teaching and learning in the 21st century is filled with challenge and opportunity, especially when teaching students for whom English is a new language.Let’s begin by showing you one school’s continual effort to bring their Englishlearners into the 21st century using the Internet and other technologies in waysthat support their academic and language learning, while promoting social development, self-esteem, and individual empowerment.3M01 PERE5153 06 SE C01.indd 34/13/12 1:59 PM

4Chapter 1 English Learners in 21st-Century ClassroomsAt a California elementary school serving more than 50 percent Englishlearners, students use the Internet and other digital technologies tocreate and present individual multimedia projects they work on overthe course of the school year. Fifth-graders, for example, chooseeither PowerPoint or iMovie to present an autobiography writtenon the computer and illustrated with drawings or digital photos oftheir home, their family, and other important people in their lives.The autobiographies include a vision of themselves in a future careerfollowed by a dramatic video recording in which they read their own“This I Believe Statement.” Throughout the process, students help eachother and are supported by constructive feedback from their peers,parents, and teacher. In the production stage, students embed a voiceover narration with text and illustrations indicating the skills andsupport they will need to achieve their desired career goal. At centersin their two-computer classrooms, the fifth-graders use digital audioand video recorders, scanners, computer software, and the Internetto conduct research, create storyboards, and produce their finalPowerPoint or iMovie piece. At the end of the year, students presenttheir multimedia projects to their parents, peers, and friends in theprimary grades.This vignette describes a very different kind of classroom from the one manyof us enjoyed in the past. Indeed, we live in awesome times filled with rapidchanges—changes that proffer both grand opportunities and daunting challengesaffecting everyone, including K–12 teachers. Technological advances are changingthe way we live and learn, from interactive Internet to social networking sitesto smartphones with built-in cameras and beyond. Communication hasbecome available instantaneously worldwide. A dazzling array of informationis available at the touch of a button. Privacy has diminished and secrets arealmost impossible to keep, even at top levels of government. These technologicaladvances not only impact our personal lives but they also affect the politicaland economic realities of countries throughout the world. Economically, forexample, consider the outsourcing of customer service jobs by U.S. companiesand the increasing globalization of many businesses. Politically, Internet andcell phone communication has facilitated uprisings against dictatorships andnetworking among subversive organizations. More than ever, human beings areconnecting with others on the planet through digital and Internet technology. Andsignificantly, that technology is constantly changing.As the world grows smaller through communication, people are becomingmore mobile in a variety of ways. For example, international migrations havechanged the demographics of many countries, including the United States,Canada, and the European countries. The coexistence of people from diversecultures, languages, and social circumstances has become the rule rather thanthe exception, demanding new levels of tolerance, understanding, and patience.Even as immigration has changed the face of countries such as the United States,occupational mobility has added another kind of diversity to the mix. Earliergenerations planned on finding a job and keeping it until retirement at age 65.Today, the average wage earner will change jobs as a many as five times priorto retirement. These changes are due to the rapid evolution of the job marketM01 PERE5153 06 SE C01.indd 44/13/12 1:59 PM

Chapter 1 English Learners in 21st-Century Classrooms5as technology eliminates or outsources some jobs, while creating new ones thatrequire retooling and retraining. Even as immigrants arrive and people changejobs, the gap between rich and poor continues to widen in the United States,threatening social mobility for those in poverty and the working class. Thesechanging demographics thus add another element to the ever-shifting field onwhich we work and play. Now, more than ever, the education we provide ouryouth must meet the needs of a future defined by constant innovation and change.Into this field of challenge and change, teachers provide the foundation onwhich all students, including English learners, must build the competence andflexibility needed for success in the 21st century. The vignette illustrates some ofthe technological tools now available to young people as they envision themselvesin a personally productive future and express their dreams in a multimedia formatto share with others. It is our hope that this book will provide you the foundationsto help your students envision and enact positive futures for themselves. To thatend, we offer you a variety of theories, teaching strategies, assessment techniques,and learning tools to help you meet the needs of your students and the challengesthey will face today and in the future. Our focus is K–12 students who are inthe process of developing academic and social competence in English as a newlanguage.There are a number of basic terms and acronyms in the field of Englishlearner education that we want to define for you here. We use the term Englishlearners (ELs) to refer to non-native English speakers who are learning English inschool. Typically, English learners speak a primary language other than English athome, such as Spanish, Cantonese, Russian, Hmong, Navajo, or other language.English learners vary in how well they know the primary language. Of course,they vary in English language proficiency as well. Those who are beginners tointermediates in English have been referred to as limited English proficient (LEP),a term that is used in federal legislation and other official documents. However,as a result of the pejorative connotation of “limited English proficient,” mosteducators prefer the terms English learners, English language learners, nonnative English speakers, and second language learners to refer to students whoare in the process of learning English as a new language.Over the years, another English learner category has emerged: long-termEnglish learner (Olsen, 2010). Long-term ELs are students who have lived inthe United States for many years, have been educated primarily in the UnitedStates, may speak very little of the home language, but have not developedadvanced proficiency in English, especially academic English. They may not evenbe recognized as non-native English speakers. Failure to identify and educatelong-term English learners poses significant challenges to the educational systemand to society. In this book, we offer assessment and teaching strategies for“beginning” and “intermediate” English learners. If you are teaching long-termEnglish learners, you will likely find excellent strategies described in the sectionsfor intermediate English learners. Some beginning strategies may apply as well.The terms English as a Second Language (ESL) and English for Speakers ofOther Languages (ESOL) are often used to refer to programs, instruction, anddevelopment of English as a non-native language. We use the term ESL becauseit is widely used and descriptive, even though what we refer to as a “secondlanguage” might actually be a student’s third or fourth language. A synonym forESL that you will find in this book is English language development (ELD).M01 PERE5153 06 SE C01.indd 54/13/12 1:59 PM

6Chapter 1 English Learners in 21st-Century ClassroomsNew Learning Tools as Technology EvolvesMany of your students in K–12 classrooms have substantial experience withcomputers, cell phones, the Internet, and other digital technologies. Other studentsmay have little or no such experience at all. In any case, all your students will needto become proficient at using the Internet and other technologies for academiclearning. In particular, they will need to learn safe, efficient, and critical Internetuse, and they will need to acquire the flexibility to adapt to new applicationsthat develop each day. For example, consider the advances in the Internet itself thathave occurred over the decades. Early on, the Internet provided one-way accessto websites, creating what amounted to a very large encyclopedia, sometimesreferred to as Web 1.0. You will want to help your students use Web 1.0 to access,evaluate, and use information appropriately, while applying the rules of safe andethical Internet use. The term Web 2.0 is used to define the more collaborativecapabilities of the Internet that became available as Internet technology evolved.Using blogs, for example, students may create an ongoing conversation aboutsubjects they are studying. With wikis, students may collaborate to create a storyor an encyclopedia for the class similar to Wikipedia. We mention these two toolsbriefly here and offer details on how to use them in subsequent chapters. Bearin mind, however, that there are over 200 webtools available to teachers, andthat number grows daily, even as web technology continues to evolve (Leu, Leu,& Coiro, 2004; Solomon & Schrum, 2010). Throughout our book we integrateways teachers are using the Internet and other digital tools to enhance and extendstudent learning and to prepare them for success in the 21st century.Who Are English Language Learners?Students who speak English as a non-native language live in all areas of the UnitedStates, and their numbers have steadily increased over the last several decades.Between 1994 and 2004, for example, the number of ELs nearly doubled, andhas continued to increase in subsequent years. By 2008–2009, the number hadreached 5,346,673. Between 1999 and 2009, U.S. federal education statisticsindicated that EL enrollment increased at almost seven times the rate of totalstudent enrollment (www.ncela.gwu.edu/faqs/). States with the highest numbersof English learners are California, Texas, Florida, New York, and Illinois. In recentyears, however, EL populations have surged in the Midwest, South, Northwest,and in the state of Nevada. For the 2000–2001 school year, the last year forwhich the federal government required primary language data, states reportedmore than 460 different primary languages, with Spanish comprising by far themost prevalent, spoken by about 80 percent of ELs (Loeffler, 2005).It may surprise you to learn that in the United States, native-born Englishlearners outnumber those who were born in foreign countries. According to onesurvey, only 24 percent of ELs in elementary school were foreign born, whereas44 percent of secondary school ELs were born outside the United States (Capps,Fix, Murray, Ost, Passel, & Herwantoro, 2005). Among those English learnerswho were born in the United States, some have roots in U.S. soil that go back forcountless generations, including American Indians of numerous tribal heritages.M01 PERE5153 06 SE C01.indd 64/13/12 1:59 PM

How Can I Get to Know My English Learners?7Others are sons and daughters of immigrants who left their home countries insearch of a better life. Those who are immigrants may have left countries brutallytorn apart by war or political strife in regions such as Southeast Asia, CentralAmerica, the Middle East, and Eastern Europe. Finally, there are those who havecome to be reunited with families who are already settled in the United States.Whether immigrant or native born, each group brings its own history andculture to the enterprise of schooling (Heath, 1986). Furthermore, each groupcontributes to the rich tapestry of languages and cultures that form the basic fabric ofthe United States. Our first task as teachers, then, is to become aware of our students’personal histories and cultures, so as to understand their feelings, frustrations, hopes,and aspirations. At the same time, as teachers, we need to look closely at ourselvesto discover how our own culturally ingrained attitudes, beliefs, assumptions, andcommunication styles play out in our teaching and affect our students’ learning. Bydeveloping such understanding, we create the essential foundation for meaningfulinstruction, including reading and writing instruction. As understanding grows,teachers and students alike can come to an awareness of both diversity and universalsin human experience as shared in this poem by a high school student who emigratedwith her parents from Cambodia (Mullen & Olsen, 1990).“You and I Are the Same”*You and I are the samebut we don’t let our hearts see.Black, White and AsianAfrica, China, United States and all othercountries around the worldPeel off their skinLike you peel an orangeSee their fleshlike you see in my heartPeel off their meatAnd peel my wickedness with it tooUntil there’s nothing leftbut bones.Then you will see that you and Iare the same.How Can I Get to Know My English Learners?Given the variety and mobility among English learners, it is likely that most teachers, including specialists in bilingual education or ESL, will at some time encounter students whose language and culture they know little about. Perhaps you arealready accustomed to working with students of diverse cultures, but if you arenot, how can you develop an understanding of students from unfamiliar linguisticand cultural backgrounds? Far from a simple task, the process requires not only*Kien Po, “You and I Are the Same.” 1990. San Francisco: California Tomorrow. Reprinted withpermission of the author.M01 PERE5153 06 SE C01.indd 74/13/12 1:59 PM

8Chapter 1 English Learners in 21st-Century Classroomsfact finding but also continual observation and interpretation of children’s behavior, combined with trial and error in communication. Thus the process is one thatmust take place gradually.Getting Basic Information When a New Student ArrivesWhen a new student arrives, we suggest three initial steps. First of all, begin tofind out basic facts about the student. What country is the student from? Howlong has he or she lived in the United States? Where and with whom is the studentliving? If an immigrant, what were the circumstances of immigration? Some children have experienced traumatic events before and during immigration, and theprocess of adjustment to a new country may represent yet another link in a chainof stressful life events (Olsen, 1998). What language or languages are spoken inthe home? If a language other than English is spoken in the home, the next stepis to assess the student’s English language proficiency in order to determine whatkind of language education support is needed. It is also helpful to assess primarylanguage proficiency where feasible.Second, obtain as much information about the student’s prior school experiences as possible. School records may be available if the child has already been enrolled in a U.S. school. However, you may need to piece the information togetheryourself, a task that requires resourcefulness, imagination, and time. Some schooldistricts collect background information on students when they register or uponadministration of language proficiency tests. Thus, your own district office is onepossible source of information. In addition, you may need the assistance of someone who is familiar with the home language and culture, such as another teacher,a paraprofessional, or a community liaison, who can ask questions of parents,students, or siblings. Keep in mind that some children may have had no previous schooling, despite their age, or perhaps their schooling has been interrupted.Other students may have attended school in their home countries.Students with prior educational experience bring various kinds of knowledge to school subjects and may be quite advanced. Be prepared to validate yourstudents for their special knowledge. We saw how important this was for fourthgrader Li Fen, a recent immigrant from mainland China who found herself in aregular English language classroom, not knowing a word of English. Li Fen was abright child but naturally somewhat reticent to involve herself in classroom activities during her first month in the class. She made a real turnaround, however, theday the class was studying long division. Li Fen accurately solved three problemsat the chalkboard in no time at all, though her procedure differed slightly fromthe one in the math book. Her classmates were duly impressed with her mathematical competence and did not hide their admiration. Her teacher, of course,gave her a smile with words of congratulations. From that day forward, Li Fenparticipated more readily, having earned a place in the class.When you are gathering information on your students’ prior schooling, it’simportant to find out whether they are literate in their home language. If they are,you might encourage them to keep a journal using their native language, and ifpossible, you should acquire native language books, magazines, or newspapersto have on hand for the new student. In this way, you validate the student’s language, culture, and academic competence, while providing a natural bridge toEnglish reading. Make these choices with sensitivity, though, building on positiveM01 PERE5153 06 SE C01.indd 84/13/12 1:59 PM

How Can I Get to Know My English Learners?9responses from your student. Bear in mind, for example, that some newcomersmay not wish to be identified as different from their classmates. We make thiscaveat because of our experience with a 7-year-old boy, recently arrived fromMexico, who attended a school where everyone spoke English only. When wespoke to him in Spanish, he did not respond, giving the impression that he didnot know the language. When we visited his home and spoke Spanish with hisparents, he was not pleased. At that point in his life, he may have wanted nothingmore than to blend into the dominant social environment—in this case an affluent, European American neighborhood saturated with English.The discomfort felt by this young boy is an important reminder of the internal conflict experienced by many youngsters as they come to terms with life in anew culture. As they learn English and begin to fit into school routines, they embark on a personal journey toward a new cultural identity. If they come to rejecttheir home language and culture, moving toward maximum assimilation into thedominant culture, they may experience alienation from their parents and family.A moving personal account of such a journey is provided by journalist RichardRodriquez in his book Hunger of Memory (1982). Another revealing accountis the lively, humorous, and at times, brutally painful memoir, Burro Genius, bynovelist Victor Villaseñor (2004). Villaseñor creates a vivid portrayal of a youngboy seeking to form a positive identity as he struggles in school with dyslexiaand negative stereotyping of his Mexican language and culture. Even if Englishlearners strive to adopt the ways of the new culture without replacing those ofthe home, they will have departed significantly from many traditions their parentshold dear. Thus, for many students, the generation gap necessarily widens to theextent that the values, beliefs, roles, responsibilities, and general expectations differ between the home culture and the dominant one. Keeping this in mind mayhelp you empathize with students’ personal conflicts of identity and personal lifechoices.The third suggestion, then, is to become aware of basic features of the homeculture, such as religious beliefs and customs, food preferences and restrictions,and roles and responsibilities of children and adults (Ovando, Collier, & Combs,2003; Saville-Troike, 1978). These basic bits of information, although sketchy,will guide your initial interactions with your new students and may help youavoid asking them to say or do things that may be prohibited or frowned on in thehome culture, including such common activities as celebrating birthdays, pledgingallegiance to the flag, and eating hot dogs. Finding out basic information also provides a starting point from which to interpret your newcomer’s responses to you,to your other students, and to the ways you organize classroom activities. Just asyou make adjustments, your students will also begin to make adjustments as theygrow in the awareness and acceptance that ways of acting, dressing, eating, talking, and behaving in school are different to a greater or lesser degree from whatthey may have experienced before.Classroom Activities That Let You Get to KnowYour StudentsSeveral fine learning activities may also provide some of the personal information you need to help you know your students better. One way is to have all yourstudents write an illustrated autobiography, “All about Me” or “The Story of MyM01 PERE5153 06 SE C01.indd 94/13/12 1:59 PM

10Chapter 1 English Learners in 21st-Century ClassroomsLife.” Each book may be bound individually, or all the life stories may be boundtogether and published in a class book, complete with illustrations or photographs. This activity might serve as the beginning of a multimedia presentation,such as the one described in the vignette at the beginning of this chapter. Alternatively, student stories may be posted on the bulletin board for all to read. Thisassignment lets you in on the lives of all your students and permits them to get toknow, appreciate, and understand each other as well. Of particular importance,this activity does not single out your newcomers because all your students will beinvolved.Personal writing assignments like this lend themselves to various grade levels because personal topics remain pertinent across age groups even into adulthood. Students who speak little or no English may begin by illustrating a seriesof important events in their lives, perhaps to be captioned with your assistanceor that of another student. In addition, there are many ways to accommodatestudents’ varying English writing abilities. For example, if students write moreeasily in their native tongue than in English, allow them to do so. If needed, aska bilingual student or paraprofessional to translate the meaning for you. Be sureto publish the student’s story as written in the native language; by doing so, youwill both validate the home language and expose the rest of the class to a differentlanguage and its writing system. If a student knows some English but is not yetable to write, allow her or him to dictate the story to you or to another studentin the class.Another way to begin to know your students is to start a dialogue journalwith them. Provide each student with a blank journal and allow the student todraw or write in the language of the student’s choice. You may then respond tothe students’ journal entries on a periodic basis. Interactive dialogue journals,When students shareinformation abouttheir home countries,they grow in self- esteem while broadening the horizons oftheir peers.M01 PERE5153 06 SE C01.indd 104/13/12 1:59 PM

How Can I Get to Know My English Learners?11described in detail in Chapters 5 and 7, have proven useful for English learners ofall ages (Kreeft, 1984). Dialogue journals make an excellent introduction to literacy and facilitate the development of an ongoing personal relationship betweenthe student and you, the teacher. As with personal writing, this activity is appropriate for all students, and if you institute it with the entire class, you provide away for newcomers to participate in a “regular” class activity. Being able to dowhat others do can be a source of great pride and self-satisfaction to students whoare new to the language and culture of the school.Finally, many teachers start the school year with a unit on a theme such as“Where We Were Born” or “Family Origins.” Again, this activity is relevant toall students, whether immigrant or native born, and it gives both you and yourstudents alike a chance to know more about themselves and each other. A typicalactivity with this theme is the creation of a world map with a string connectingeach child’s name and birthplace to your city and school. Don’t forget to put yourname on the list along with your birthplace. From there, you and your studentsmay go on to study more about the various regions and countries of origin. IfInternet access is available, students might search the Web for information ontheir home countries to include in their reports. The availability of informationin many world languages may be helpful to students who are literate in theirhome languages. Clearly, this type of theme leads in many directions, includingthe discovery of people in the community who may be able to share informationabout their home countries with your class. Your guests may begin by sharingfood, holiday customs, art, or music with students. Through such contact, themestudies, life stories, and reading about cultures in books such as those listed inExample 1.1, you may begin to become aware of some of the more subtle aspectsof the culture, such as how the culture communicates politeness and respect orhow the culture views the role of children, adults, and the school. If you are luckyenough to find such community resources, you will not only enliven your teaching but also broaden your cross-cultural understanding and that of your students(Ada & Zubizarreta, 2001).Not all necessary background information will emerge from these classroom activities. You will no doubt want to look into cultural, historical, and Example 1.1Useful Books on Multicultural TeachingBanks, J. A. (2009). Teaching strategies for ethnic studies (8th ed.). Boston: Allynand Bacon.Darder, A. (1991). Culture and power in the classroom: A critical foundation forbicultural education. Westport, CT: Bergin & Garvey.Igoa, C. (1995). The inner world of the immigrant child. New York: St. Martin’sPress.Nieto, S., & Bode, P. (2011). Affirming diversity: The sociopolitical context ofmulticultural education (6th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.Tiedt, P. L., & Tiedt, I. M. (2010). Multicultural teaching: A handbook of activities,information, and resources (8th ed.). Boston: Allyn and Bacon.M01 PERE5153 06 SE C01.indd 114/13/12 1:59 PM

12Chapter 1 English Learners in 21st-Century Classroomsgeographical resources available at your school, on the Internet, or in your community library. In addition, you may find resource personnel at your school, including paraprofessionals and resource teachers, who can help with specific questions or concerns. In the final analysis, though, your primary source of information is the students themselves as you interrelate on a day-to-day basis.How Do Cultural Differences Affect Teachingand Learning?The enterprise of teaching and learning is deeply influenced by culture in a varietyof ways. To begin with, schools themselves reflect the values, beliefs, attitudes,and practices of the larger society. In fact, schools represent a major socializingforce for all students. For English learners, moreover, school is often the primarysource of adaptation to the language and culture of the larger society. It is herethat students may begin to integrate aspects of the new culture as their own, whileretaining, rejecting, or modifying traditions from home.Teachers and students bring to the classroom particular cultural orientationsthat affect how they perceive and interact with each other in the classroom. Asteachers of English learners, most of us will encounter students whose languagesand cultures differ from our own. Thus, we need to learn about our students andtheir cultures while at the same time reflecting on our own culturally rooted behaviors that may facilitate or interfere with te

Teaching and learning in the 21st century is filled with challenge and opportu-nity, especially when teaching students for whom English is a new language. Let’s begin by showing you one school’s continual effort to bring their English learners into the 21st century