Transcription

MORAL LETTERS TO LUCILIUS

THE ANCIENT STOIC SOURCES SERIESpublished by Stoici Civitas PressThe Ancient Stoic Sources Series has the aim of bringing all of the availablewritings of the school into a single affordable series. Each volume is a carefuledition of public domain texts, reformatted in easy-to-read type. Designed forthe student of Stoicism, the main text of each volume includes wide outsidemargins for notes, a wide interline for highlighting and underlining, andnumbered sections taken for the original Greek or Latin for ease of reference.All volumes will be made available as they are released E COMPLETE MORAL LETTERS TO LUCILIUS – SENECAtr. by Richard Gummere*TO HIMSELF – THE MEDITATIONS OF MARCUS AURELIUStr. by George Long*THE COMPLETE DIALOGUES AND ESSAYS – SENECAtr. by John Basore*THE DISCOURSES & HANDBOOK OF EPICTETUS –AS REPORTED BY ARRIANtr. by William Oldfather*THE LECTURES – MUSONIUS RUFUStr. Cora Lutz*STOIC COMMENTARIES AND PARADOXES – CICEROseveral translators*THE LIVES & DOCTRINES OF THE STOIC PHILOSOPHERS –DIOGENES LAERTIUStr. by C.D. Yonge*forthcoming

The CompleteMORAL LETTERS TO LUCILIUSWritten by L. Annaeus SenecaTranslate by Richard M. GummereUpdated, Annotated and Expanded byMichel DawTHE ANCIENT STOIC SOURCES SERIESARRANGED AND NEWLY TYPESET BYMICHEL DAWWITH A SPECIAL PROLOGUE BYTHE TRANSLATORSTOICI CIVITAS PRESS OTTAWA

The main contents of this book have been compiled from the translationof the Letters of Seneca by Richard M. Gummere Ph.D., of Haverford Collegepublished by G. Putnam’s and Son in three volumes between 1920 and 1925.The Prologue is taken completely from The Modern Note in Seneca's Letters,also by Richard M. Gummere, originally published in the journal of ClassicalPhilology, Vol. 10, No. 2 (Apr., 1915), pp. 139-150.These documents now sit in the public domain.The text has been newly typeset using Garamond 10 pt. with an interlineof 1.15. Titles are in Garamond 14 pt. This document has been producedusing Microsoft Word 2010 and Adobe Acrobat X.The Preface and additional content are 2013 Michel Daw. All rights reserved.ISBN 978-1-304-66806-6For more information on the practice of modern Stoicism,visit thestoiclife.org or email thestoiclife@gmail.com.

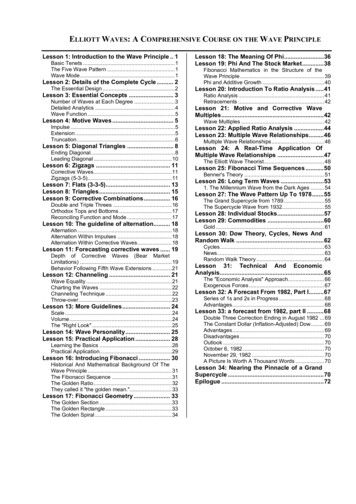

ContentsPreface . iPrologue: The Modern Note in Seneca's Letters . iiiIntroduction .xiiiBOOK I . 1I. ON SAVING TIME. 1II. ON DISCURSIVENESS IN READING . 3III. ON TRUE AND FALSE FRIENDSHIP . 5IV. ON THE TERRORS OF DEATH. 7V. ON THE PHILOSOPHER'S MEAN . 9VI. ON SHARING KNOWLEDGE .11VII. ON CROWDS .13VIII. ON THE PHILOSOPHER'S SECLUSION .16IX. ON PHILOSOPHY AND FRIENDSHIP.19X. ON LIVING TO ONESELF .24XI. ON THE BLUSH OF MODESTY .26XII. ON OLD AGE .28BOOK II.31XIII. ON GROUNDLESS FEARS .31XIV. ON THE REASONS FOR WITHDRAWING FROM THE WORLD .35XV. ON BRAWN AND BRAINS .39XVI. ON PHILOSOPHY, THE GUIDE OF LIFE .42XVII. ON PHILOSOPHY AND RICHES.44XVIII. ON FESTIVALS AND FASTING .47XIX. ON WORLDLINESS AND RETIREMENT.50XX. ON PRACTISING WHAT YOU PREACH .53XXI. ON THE RENOWN WHICH MY WRITINGS WILL BRING YOU.56Book III .59XXII. ON THE FUTILITY OF HALF-WAY MEASURES .59XXIII. ON THE TRUE JOY WHICH COMES FROM PHILOSOPHY.63

XXIV. ON DESPISING DEATH . 66XXV. ON REFORMATION . 72XXVI. ON OLD AGE AND DEATH. 74XXVII. ON THE GOOD WHICH ABIDES. 76XXVIII. ON TRAVEL AS A CURE FOR DISCONTENT. 78XXIX. ON THE CRITICAL CONDITION OF MARCELLINUS. 80Book IV . 83XXX. ON CONQUERING THE CONQUEROR . 83XXXI. ON SIREN SONGS . 87XXXII. ON PROGRESS . 90XXXIII. ON THE FUTILITY OF LEARNING MAXIMS . 92XXXIV. ON A PROMISING PUPIL. 95XXXV. ON THE FRIENDSHIP OF KINDRED MINDS. 96XXXVI. ON THE VALUE OF RETIREMENT . 97XXXVII. ON ALLEGIANCE TO VIRTUE . 100XXXVIII. ON QUIET CONVERSATION . 102XXXIX. ON NOBLE ASPIRATIONS. 103XL. ON THE PROPER STYLE FOR A PHILOSOPHER'S DISCOURSE . 105XLI. ON THE GOD WITHIN US. 109Book V . 111XLII. ON VALUES. 111XLIII. ON THE RELATIVITY OF FAME. 113XLIV. ON PHILOSOPHY AND PEDIGREES. 114XLV. ON SOPHISTICAL ARGUMENTATION . 116XLVI. ON A NEW BOOK BY LUCILIUS. 119XLVII. ON MASTER AND SLAVE . 120XLVIII. ON QUIBBLING AS UNWORTHY OF THE PHILOSOPHER. 124XLIX. ON THE SHORTNESS OF LIFE . 128L. ON OUR BLINDNESS AND ITS CURE . 131LI. ON BAIAE AND MORALS. 133

LII. ON CHOOSING OUR TEACHERS. 136Book VI . 139LIII. ON THE FAULTS OF THE SPIRIT. 139LIV. ON ASTHMA AND DEATH. 142LV. ON VATIA'S VILLA. 144LVI. ON QUIET AND STUDY . 147LVII. ON THE TRIALS OF TRAVEL . 151LVIII. ON BEING. 153LIX. ON PLEASURE AND JOY. 161LX. ON HARMFUL PRAYERS. 166LXI. ON MEETING DEATH CHEERFULLY . 167LXII. ON GOOD COMPANY . 168Book VII . 169LXIII. ON GRIEF FOR LOST FRIENDS . 169LXIV. ON THE PHILOSOPHER'S TASK . 173LXV. ON THE FIRST CAUSE . 175LXVI. ON VARIOUS ASPECTS OF VIRTUE. 181LXVII. ON ILL-HEALTH AND ENDURANCE OF SUFFERING . 192LXVIII. ON WISDOM AND RETIREMENT. 196LXIX. ON REST AND RESTLESSNESS . 199Book VIII. 200LXX. ON THE PROPER TIME TO SLIP THE CABLE . 200LXXI. ON THE SUPREME GOOD . 206LXXII. ON BUSINESS AS THE ENEMY OF PHILOSOPHY . 214LXXIII. ON PHILOSOPHERS AND KINGS. 217LXXIV. ON VIRTUE AS A REFUGE FROM WORLDLY DISTRACTIONS. 221Book IX . 229LXXV. ON THE DISEASES OF THE SOUL . 229LXXVI. ON LEARNING WISDOM IN OLD AGE. 233LXXVII. ON TAKING ONE'S OWN LIFE . 241

LXXVIII. ON THE HEALING POWER OF THE MIND . 246LXXIX. ON THE REWARDS OF SCIENTIFIC DISCOVERY . 253LXXX. ON WORLDLY DECEPTIONS. 257Book X . 260LXXXI. ON BENEFITS . 260LXXXII. ON THE NATURAL FEAR OF DEATH. 268LXXXIII. ON DRUNKENNESS. 275Books XI-XIII . 281LXXXIV. ON GATHERING IDEAS . 281LXXXV. ON SOME VAIN SYLLOGISMS . 285LXXXVI. ON SCIPIO'S VILLA . 294LXXXVII. SOME ARGUMENTS IN FAVOUR OF THE SIMPLE LIFE . 299LXXXVIII. ON LIBERAL AND VOCATIONAL STUDIES . 308Book XIV . 319LXXXIX. ON THE PARTS OF PHILOSOPHY . 319XC. ON THE PART PLAYED BY PHILOSOPHY IN THE PROGRESS OF MAN . 325XCI. ON THE LESSON TO BE DRAWN FROM THE BURNING OF LYONS. 338XCII. ON THE HAPPY LIFE. 344Book XV . 352XCIII. ON THE QUALITY, AS CONTRASTED WITH THE LENGTH, OF LIFE. 352XCIV. ON THE VALUE OF ADVICE . 356XCV. ON THE USEFULNESS OF BASIC PRINCIPLES . 372Book XVI . 388XCVI. ON FACING HARDSHIPS . 388XCVII. ON THE DEGENERACY OF THE AGE . 390XCVIII. ON THE FICKLENESS OF FORTUNE . 394XCIX. ON CONSOLATION TO THE BEREAVED . 398C. ON THE WRITINGS OF FABIANUS. 405Books XVII - XVIII . 408CI. ON THE FUTILITY OF PLANNING AHEAD . 408CII. ON THE INTIMATIONS OF OUR IMMORTALITY. 412

CIII. ON THE DANGERS OF ASSOCIATION WITH OUR FELLOW-MEN. 419CIV. ON CARE OF HEALTH AND PEACE OF MIND . 420CV. ON FACING THE WORLD WITH CONFIDENCE. 428CVI. ON THE CORPOREALITY OF VIRTUE . 430CVII. ON OBEDIENCE TO THE UNIVERSAL WILL. 432CVIII. ON THE APPROACHES TO PHILOSOPHY . 435CIX. ON THE FELLOWSHIP OF WISE MEN. 444Book XIX . 448CX. ON TRUE AND FALSE RICHES . 448CXI. ON THE VANITY OF MENTAL GYMNASTICS . 452CXII. ON REFORMING HARDENED SINNERS. 453CXIII. ON THE VITALITY OF THE SOUL AND ITS ATTRIBUTES. 454CXIV. ON STYLE AS A MIRROR OF CHARACTER. 460CXV. ON THE SUPERFICIAL BLESSINGS . 467CXVI. ON SELF-CONTROL. 472CXVII. ON REAL ETHICS AS SUPERIOR TO SYLLOGISTIC SUBTLETIES. 474Book XX . 481CXVIII. ON THE VANITY OF PLACE-SEEKING. 481CXIX. ON NATURE AS OUR BEST PROVIDER . 485CXX. MORE ABOUT VIRTUE. 489CXXI. ON INSTINCT IN ANIMALS. 495CXXII. ON DARKNESS AS A VEIL FOR WICKEDNESS. 500CXXIII. ON THE CONFLICT BETWEEN PLEASURE AND VIRTUE . 505CXXIV. ON THE TRUE GOOD AS ATTAINED BY REASON . 509Appendix . 514Index of proper names . 515Subject index . 527

MORAL LETTERS TO LUCILIUSBY SENECA

PREFACE“I see in myself, Lucilius, not just an improvement but a transformation.”(Seneca, Moral Letters 6.1)This is a suprisingly unique book.Suprising by the fact that a book of this kind has not been published inwell over a century. While there have been various collections and selections ofthe Letters of Seneca published in recent years, no single volume containing all124 letters, translated into English, has been published to date.Surprising aslo because on more than one occasion, these corresponceswith Lucilius have been recognized as complete course of Stoic training,following Seneca’s student’s development from neophyte in the philosophy ofthe porch to a teacher in his own right. Their narrative and pedagogical unitycan only be experienced and understood through the flow of the ideas,situations, success and failure in the application of Stoic principles, present andprogressing through all of the letters. Despite this, the letters continue to‘picked-over’ by publishers for only the choicest bits, a practice that Senecahimself decries in more than one letter.Surprising, finally, because I am the one to do this. This last is probablymore of an astonishment to me than to some of my friends in the Stoiccommunity. Nevertheless, here am I publishing the first volume of the AncientStoic Sources Series to the world.Seneca was my ‘gateway’ to Stoicism, a philosopy and practice that hasinformed and reformed my life over the past decade. I was fist introduced toboth Seneca and Stoicism through the first small volume of the Penguin GreatIdeas series, Seneca’s ‘On the Shortness of Life.’ Through many adventuresand misadventures, my wife Pamela and I founded a local Stoic community,centered around Stoic study groups, public presentations and workshops toinform any who might be interested in the value and reward of an ‘examinedlife.’Three publications have had a profound effect upon my understandingand appreciation of Seneca’s works, and more specifically of his letters. Thefirst was Brad Inwood’s ‘Reading Seneca: Stoic Philosophy at Rome’ published byOxford University Press in 2008. This excellent book gathers together in asingle volume many of Inwood’s insightful essays regarding the times,conditions and influences in Seneca’s writings, providing much needed contextfor 21st century readers.The second work is important because of the apparently hypocrisyascribed to Seneca. His letters and essays describe a man who, though wealthy

Prefaceand powerful in his day, was nevertheless keenly aware of the fragility andemptiness of these things and relied instead on his own moral stregnths for hisvalue and core. The charges of hypocrisy, which have proven to be remarkablytenatious over two millenia, stem from a single questionable source, and havebeen blindly echoed and embelished as they passed from pen to pen.A key document in challenging this false perception has been AnnaMotto’s article ‘Seneca on Trial: The Case of the Opulent Stoic’, published in the TheClassical Journal in 1966. a In it, she analyses not the charges themselves, butthe reliability and possible motivations of Seneca’s only accuser, PubliusSuillius, a nefarious individual with a personal grudge against Seneca, and aknown perjuror, blackmailer and mercenary. The article itself served toeliminate any remaining doubts as to Seneca’s sincerity in writing the letters.Finally, John Schaffer’s ‘Seneca’s Epistulae Morales as Dramatized Education’,recently published in the 2011 edition of Classical Philology, provided thenecessary impetus for completing this daunting project. In it he argues that thetrue value of the letters is to be found in the flow of the themes throughout allthe letters, the selection of a subject and its unfolding, the sucesses and failuresof practice and principle, the worlds outside and in as they are revealed inpersonal vignettes. Most importantly, he proposes that the letters themselvesare a course in Stoicism, the development of the characters of both Luciliusand Seneca, and their mutual friendship on the path to sagehood.In addion to the Introduction, which was included in the originaltranslation of these letters, I have included as a prologue Gummere’s 1914essay, The Modern Note in Seneca's Letters. Though the examples he uses aresomewhat dated, the themes echoe those mentioned above, and provide aninteresting insight into the translator’s mind.It is for these reasons, and more, that this volume has come together. Itis through not only an effort of will (which would have proven insufficient),that you now hold this book in your hands. The participants in the Stoicworkshops have been instrumental in both my own Stoicism, as well as mydesire to publish this volume for their benefit. Their yearning for somethingmore for their lives led them to Stoicism, and they are my teachers.My principle thanks, however, goes to my wife and fellow Stoic. She hasbeen my muse and my editor, my biggest fan and keenest critic. This book istherefore, naturally, dedicated to her.June 2, 2013, Ottawa, ONMichel Dawco-founder of thestoiclife.orgFor more information on the practice of modern Stoicism,visit thestoiclife.org or email thestoiclife@gmail.com.aiiVol. 61, No. 6 (Mar., 1966), pp. 254-258

For Pamelabecause“Life,if you knowhow to live it,is long.”

PROLOGUE:THE MODERN NOTE IN SENECA'S LETTERS aThe literary world is prone to eye askance one who mingles types, or, toborrow a phrase from Latin comedy, practices “contaminatio.” In the drama,lyric, no matter how inspiring, must be subordinate to the action; for this reasonthe public has not bestowed immortality upon George Darley, the “belatedElizabethan.” Nor will the lyric itself permit much moralizing; for this reasonmany of Wordsworth's poems met with a storm of disapproval. If the epicceases to tell a story and dwells too much upon description, the reader iswearied; for this reason the narrative poetry of Southey and Landor is no longerread except by the specialist or the curio-hunter. Seneca was similarlyhandicapped; his prose could not be identified with the direct study of oratory,as could that of his father; nor with the drama of history, as Tacitus; nor with theprofessional side of Stoicism, as Epictetus; nor with the descriptive charms of anepistolographer like Pliny. In the Epistulae morales, he has tried to write a personalletter, to move his correspondent with the beauty of philosophy and virtue, todeal directly with the throbbing facts of his own epoch, and to suggest remediesfor its shortcomings. Hence he is judged at every point of approach. And it isonly by virtue of his message to the world of today, to his modern element, thatwe can insist on his enduring value. I hope to show, perhaps by a sort ofparadox, that this very mixing of literary types, this habit of scorning the“liturgical” form, has resulted in the catholicity of his appeal to so many thinkersin subsequent ages.It is well known that his successors under the empire subjected him tomuch criticism. He was a puzzle to his own contemporaries. Just as some giftedHibernian, who settles in the literary world of London and conceals a genuinemessage beneath the mask of paradox and pose, is greeted with cheers ofapproval and hisses of scorn, even so this brilliant son of a Spaniard grew topower and evoked tributes of admiration no less than doubts regarding his rightto wield that power. Tacitus sketches him as a subtly persuasive speaker, an ablebureaucrat with a dash of conscience, a safe guide for erring princes, and a foiledand disappointed hero, nothing in whose life became him like the leaving it. DioCassius sneers at his elaborate collections of curios; Juvenal and others allude tohim as proverbially rich; his own letter from exile to the freedman Polybiusa The writer of this paper is under obligations to Messrs. Hense, Waltz, Summers, and E. V.Arnold for their recent works on the text, the life, the selected Letters, and Seneca's place inRoman philosophy, respectively.

Prologuedisgusts us with its cringing despair; and Suetonius, though expressly declaringthat “the charge was vague and the accused was given no opportunity to defendhimself,” hints at scandal and connects his name with a princess of the royalhouse. We learn also that he shut his eyes to the murder of Agrippina, that hecondoned Nero's personal vices, that he managed the finances of the empiresoundly and shrewdly, that he worked in harmony with Burrus, that he was theobject of many attacks from the opposition benches in the Senate, and thatabout the year 62, when Nero's adolescent rascality had blossomed into repulsivecrime, he sought to be rid of the burdens of state. Furthermore, what can we sayin answer to the diatribes of Quintilian, Gellius, and Fronto, except to remarkthat he was a greater literary personality than any of these three critics? They flayhim alive for his un-Ciceronian sentences, his abrupt personalities, his jinglingjuxtapositions. It is not until we get into an atmosphere of detachment that wefind favorable comments.The church elevated Seneca into a pseudo-saint. The Renaissancepromoted him to the first literary rank. Montaigne relied upon him as one of twoauthors who supplied him with “timber” for his essays. Thomas Lodge says that“his divine sentences, wholesome counsels, serious exclamations against vices, inbeing but a heathen, may make us ashamed being Christians.” Rousseau, who isessentially Senecan in his attack and in his manner of thought, broke new groundin the Discourse on the Arts and Sciences. The essay (1750) embodies thefundamental principles of Rousseau's message. The writer bases his argumentagainst the refinements of knowledge by recalling the glory of poverty and thepower of the tiller of the soil. Virtue strips off trappings and reveals the soul.Cato is praised con amore; so is Socrates. A sort of socialism is outlined wherethere exists no distinction of talents. The country brook teaches more than thecity street. Virtue is the only philosophy.Thus, if one reads between the lines, one understands that whenever a newmovement of a certain type was in progress and matter from ancient literaturehad to be found as groundwork of the new theory, Seneca is frequently calledupon to furnish the material. The early church, Petrarch, Montaigne, Thomas aKempis, Lodge, and Rousseau are, in various ways, fingerposts along the road ofEuropean progress. Whenever ideas are the criterion, Seneca makes headway;whenever scientific facts predominate, Seneca loses ground.Montesquieu, that safe and sane thinker, strikes the keynote of revolt; in hisLettres persanesa he says: “The Orientals are wise enough to seek remedies againstdepression of spirit as carefully as against disease. When a European meets withaUsbek A Rhedi, 33d letter, on coffee.iv

The Modern Note In Seneca's Letterscalamity, his only resource is to read a philosopher called Seneca; but theAsiatics use beverages which can make a man merry and render pleasant thememories of former suffering.” Science now renounces ultra-idealism; AdamSmith, and the predecessors of Darwin, and the makers of new republics, andthe framers of corn laws and anti-corn laws are occupied with more practicalmatters. Curiously enough, the Romantic Movement in poetry did notcounteract scientific progress, but went hand in hand therewith; as scienceloosened its fetters, so did the Muse. Sainte-Beuve, Emerson, and MatthewArnold (the names are significant) are among the few who welcome Seneca'smessage. The forward drive of the Victorian era made a detour about thegardens of the first Christian pagan. What the twentieth century will do, no oneknows; it may be preparing another Rousseau, another Seneca. M. Maeterlinck isalternately worshiped and reproached, as was Seneca; and it is significant to notea fugitive paper which came from his hands a few years ago, of which the subjectis Death, and in which is much material resembling Seneca, and treatedaccording to the Senecan method. aLet us turn, then, to the Letters themselves, so that we may determine byinternal evidence what were these elements of revolt or of progress whichirritated Seneca's contemporaries and stirred later generations either to censureor to praise. The Epistulae morales, in spite of the real personality of the recipientLucilius, were writ

and appreciation of Seneca’s works, and more specifically of his letters. The first was Brad Inwood’s ‘Reading Seneca: Stoic Philosophy at Rome’ published by Oxford University Press in 2008. This excellent book gathers together in a single volum