Transcription

Promoting LearnerHappiness and Well-beingUNESCO Asia-PacificEducation Thematic BriefMAY 2017BackgroundHappiness and EducationThe pursuit of happiness has always been the aspirationof all human beings.1 In recent years, a growingglobal movement for happiness has been driven bymounting global challenges that are undermininghappiness in wider society; namely income inequality,growing intolerance, environmental degradation andunprecedented technological advancement. In schools,learners are also facing the repercussions of suchchallenges in a world that is more competitive, stressfueled and test-focused than ever before. At the sametime, a growing body of research has highlighted thecrucial relationship between happiness and educationalquality, whereby schools that prioritize learner wellbeing have the potential to be more effective, withbetter learning outcomes and greater achievements inlearners’ lives.2Dating back to ancient philosophies, happiness hasalways been a fascinating subject of human enquiry.Various definitions of happiness among ancient thinkerssuch as the Buddha, Aristotle and Confucius, along withthinkers from the Enlightenment era, up until the scienceof Positive Psychology today, all share similarities thatare at the heart of the Happy Schools concept. PositivePsychology has been coined the ‘science of happiness’and recognizes a number of ‘character strengths’ thatenhance happiness such as creativity, perseverance,kindness and teamwork (Peterson and Seligman, 2004).The Happy Schools Project was launched by UNESCOBangkok in June 2014 with the aim of promotinghappiness in schools through enhanced learner wellbeing and holistic development. The main outcome ofthis project was the 2016 publication Happy Schools: AFramework for Learner Well-being in the Asia-Pacific.3 Thereport features a framework of 22 criteria for a happyschool under three broad categories: 1) People, 2)Process, and 3) Place. Later that year, UNESCO and theKorean Educational Development Institute (KEDI) hosteda regional policy seminar on the theme of “Happy Schoolsfor a Happy Education” in Seoul, Republic of Korea,bringing together a group of education policymakersand practitioners for dialogue.Positive Education embraces the relationship betweeneducation and well-being and is defined as the ‘doublehelix’ of academics coupled with character and wellbeing (IPEN, 2016b). Within these concepts of happiness,three important linkages are found:1. Happiness is something collective that isobtained through friendships and relationships.2. Education is essentially holisticand multidimensional.3. Education can lead to happiness, but canalso be a source of happiness in and of itself.Therefore, we can learn to be happy, butwe can also be happy to learn.This thematic brief is a summary of the HappySchoolsProject,highlightingkeyfindingsfrom the main publication, including policyrecommendations from the aforementioned seminar.MalaysiaFunds-in-Trust

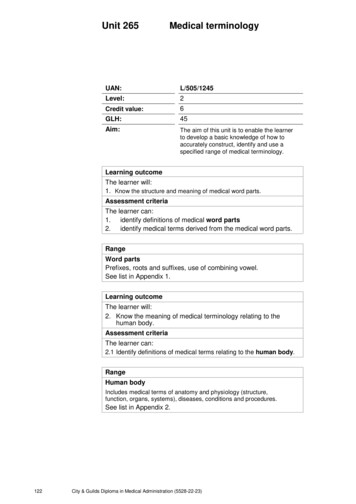

Global and Regional PoliciesHappiness is now reflected in the global policy agendaas well. In 2011, it was recognized as a fundamentalhuman right in a United Nations General Assemblyresolution. One year later, another resolution declaredthat it would be celebrated through an InternationalDay of Happiness, which falls on 20th March each year.There have also been increased efforts to measurecountries’ levels of happiness and well-being throughglobal indices including the World Happiness Reportand the Happy Planet Index. According to the 2016World Happiness Report, happiness is now increasinglyconsidered as a ‘proper measure of social progress anda goal of public policy’.4 Similarly, efforts have alsobeen made to measure student happiness through theProgramme for International Student Assessment (PISA)in its 2015 assessment. Here PISA examined the linkbetween well-being and learning outcomes throughstudent performance in school, their relationship withpeers and teachers, their home life, and how they spendtheir time outside of school.5At the national level, countries have increasinglyplaced happiness and well-being as a specific goal intheir national and education policies, or have includedelements relating to happiness in their policy frameworks.Examples include Bhutan’s 2011 policy of Educating forGross National Happiness, the Republic of Korea’s 2013policy of Happy Education for All, as well as Singapore’sintroduction of Social and Emotional Learning, to namebut a few.6 While some countries have introduced suchpolicies to emphasize local cultural values and theirimportance in sustainably developing their countries,others have developed policies in response to nationalconcerns regarding the excessive emphasis on academicdomains of learning and the consequent rising levels ofstress among learners.Happy Schools Framework and Criteria2The Happy Schools project carried out a survey withschool-level stakeholders, including students, teachers,parents and school principals to identify what constitutesa happy school. The survey obtained these perspectivesby asking four questions: 1) What makes a school happy?,2) What makes a school unhappy?, 3) What can maketeaching and learning fun and enjoyable?, and 4) Whatcan be done to make all students feel included?The responses to these questions showed the importanceof three main characteristics: 1) People – the people andthe relationships that are built within the school and thelearning process are of utmost importance; 2) Process– a fun and engaging atmosphere that allows studentsand teachers to be creative, collaborative and free; and3) Place –a warm and friendly school environmentcompletes the positive values that People and Processbring, and allows for a “Happy School”.The Happy Schools Framework (see Appendix 1) wasconstructed based on these findings, capturing the voicesand perspectives of school-level stakeholders regardingwhat constitutes a happy school. The framework is madeup of 22 criteria, falling under the three categories:People, Process and Place. Many of these criteria overlapacross the three categories and mutually reinforce eachother. The 2016 UNESCO-KEDI Asia-Pacific Regional PolicySeminar allowed education stakeholders to identify whatchallenges, opportunities and policy implications canbe associated with the Happy Schools Framework, andsome of their examples are included below.PeopleFriendships and relationships in the schoolcommunity ranked as the most important factor interms of what makes a happy school, with the findingsidentifying school practices that encourage parentalinvolvement, foster interactions and friendships betweenstudents of different grades, and school activities thatdirectly involve community members. For example,in Australia, the Geelong Grammar School’s focuson Positive Education aims to build positive relationsbetween students and teachers and encourages studentsto “engage” in the learning process. Positive educationemboldens teachers with the motto of “Learn to Live it”,allowing teachers to create the proper environment forwell-being and happiness.Stakeholders indicated that positive teacher attitudesand attributes, which include characteristics suchas kindness, enthusiasm and fairness, allow teachersto serve as inspiring, creative and happy role models

for learners. In addition, positive and collaborativevalues and practices are very important in makingschools happy. Such values and practices include love,compassion, acceptance and respect.ProcessThere is a need to create a more reasonable and fairworkload for students due to a growing imbalancebetween study and play which places an emphasis onmemorization in order to prepare for exams. In Thailand,some schools attempt to balance the education processby limiting academic study and only allowing activity/project-based learning from 2:00pm onwards. This allowsfor more student-centred learning to occur.Another important criterion under this category islearner freedom, creativity and engagement.Accordingly, a happy school should allow for learnersto express their opinions and to learn freely without thefear of making mistakes, or more importantly ‘learningwithout worrying’, so that mistakes are valued as part ofthe learning process. This also relates to useful, relevantand engaging learning content, which calls for thecontent of curricula to reflect contemporary and relevantissues, with guidance for teachers on how to make theseissues relevant to learners’ lives.Despite high academic achievement in the Republicof Korea, learner stress and disinterest in learning wascausing deep social issues. With the new policy of HappyEducation for All and the “Free-Semester Program”,students in middle school are free from mid-term andfinal exams for one semester. This allows teachers andstudents a more holistic learning approach, wherethey are free to collaborate and engage in learning. Inaddition, teachers are exempted from the archetypalform of classroom Instruction and can freely carry outmore innovative teaching activities.PlaceA warm and friendly learning environment rankedas the second most important factor for a happy schooloverall, with the findings indicating the need to place moreemphasis on greetings and smiles, as well as introducingmusic, creating more open classrooms and colourful andmeaningful displays, thereby creating a more positiveschool atmosphere. In Indonesia for example, schoolsare envisioned as a park — a place that has strong valuesand is an integral part of students’ growth.A secure environment free from bullying was alsoranked as important by respondents. The findingsidentified strategies that included more shared learningand playing activities, which enable learners to interactand better understand one another, thus reducingconflict and tensions.The need for school vision and leadership was alsohighlighted, showing how happiness can be prioritizedthrough school vision statements, mottos or slogans inorder to create more positive school atmospheres. Forexample, in Akita, Japan, schools have positive mottosand slogans, such as “Be a child with dream and selfmotivation, let’s make a happy school together”,which creates a unified vision of education for the wholeschool.ChallengesSeveral challenges remain however. As people are thebuilding blocks – and positive relationships are crucialfor the success of Happy Schools, school leaders andteachers need to embrace a paradigm shift in howeducation can embrace learner well-being.First, this includes clear visions of quality education inorder to balance an overcrowded curriculum and examfocused system. This forces teachers and students tocram too much content into limited hours, limitingcreative and engaging activities for learning. A shift tonew strategies of learning can balance the curriculum,engage students, and make learning more enjoyable.Second, effective teacher training is an issue. There isa lack of clearly articulated training and developmentprogrammes in terms of learner well-being andhappiness in education. In addition, teachers are illprepared to bring these values into the classroom, havingtraditionally been prepared to deliver content. Preparingengaging lessons, and providing learners more freedom,creativity, and ownership in their learning process, iscrucial for schools and teachers to improve motivation,both of teaching staff and for students.3

Third, ensuring a safe and nurturing environment isimportant. School bullying and poor infrastructurecontinue to allow key relationships to either fail to formor to degrade and become difficult to repair.n Providing more ownership and autonomy toschool leaders, teachers and students, to improveimplementation of curricula, management of classrooms,and to increase interest and engagement in learning.Finally, a lack of community partnerships andinvolvement of parents and stakeholders and/or poorlycommunicating the visions and goals of schools for thecommunity can limit positive gains in creating happyand healthy environments at schools.n Sharing promising and innovative schoolpractices across schools, countries, and regions in orderto identify strategies for reaching the 22 criteria in theHappy Schools Framework.Policy Recommendations andthe Way ForwardTo effect any change in current policies and practices,both the report and the policy seminar outlined theneed for a number of considerations. These includedprioritizing happiness and learner well-being within/across education policies, introducing a new generationof ‘positive teachers’ and ensuring that the values,strengths and competencies which can develop andnurture happiness among learners are recognizedand evaluated as part of curriculum and assessmentefforts. These can be considered vis-à-vis some specificrecommendations including the following:n Continuous policy dialogue to see how countriescan implement the Happy Schools Framework in theirlocal context.n An advocacy campaign to change attitudes withregard to the meaning of a ‘good quality’ education.n Effective and continuous teacher training andprofessional development to ensure that teachers arecompetent and bring positive attitudes and attributes tothe learning process. In this regard, the Happy SchoolsFramework could be translated into a teacher trainingtoolkit aiming to build the capacity of teachers, teachertrainers, and professional development programmes.4n Allowing for a balanced curriculum that embraceslearning and creativity, in addition to the accumulationof knowledge, and reduces the focus on exam-orientedachievement.n Utilizing the Happy Schools Framework as a measureof the quality of education that encompasses learnerwell-being.The Happy Schools Framework offers a different visionof the quality of education – one in which learners’unique talents, strengths and abilities are appreciated,recognized and celebrated. Evidence indicates thatprioritizing happiness and well-being can result inhigher academic achievement, which unfortunately, hasbeen undervalued by a predominant focus on ‘numbers’or test scores as indicators of the quality of education.Education policies and practices can be shaped topromote holistic learner well-being in addition toacademic success. In fact, happiness and well-being area crucial component leading to quality education andhigh learner achievement.Overall, Happy Schools asks us to question a number ofexisting policies and practices with regard to curricula,pedagogy and assessment, in order to review how theyenhance happiness and well-being through schoolsystems and beyond.References1 McMahon. 2006. Happiness: A History. New York, Grove Press.2 Layard and Hagell. 2015. A Healthy Young Mind: Transforming the Mental Health ofChildren. Helliwell et al, World Happiness Report 2015.3 UNESCO. 2016. Happy Schools: A Framework for Learner Well-being in the Asia-Pacific.4 Helliwell et. al. 2016. World Happiness Report 2016. Update.5 OECD. 2017. PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being.6 UNESCO. 2016. Happy Schools: A Framework for Learner Well-being in the Asia-Pacific.Published in 2017 by the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 7,place de Fontenoy, 75352 Paris 07 SP, France and UNESCO Bangkok Office UNESCO 2016This publication is available in Open Access under the AttributionNonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 IGO (CC-BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO) license (http://creative commons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/igo/). By using the content ofthis publication, the users accept to be bound by the terms of use of theUNESCO Open Access Repository .THA/DOC/IQE/17/05-E

Appendix 1. The Happy Schools Criteria

The Happy Schools Project was launched by UNESCO Bangkok in June 2014 with the aim of promoting happiness in schools through enhanced learner well-being and holistic development. The main outcome of this project was the 2016 publication Happy Schools: A Fr