Transcription

INCLUSION IRELANDEducation, Behaviourand ExclusionThe experience and impact of short school days’onchildren with disabilities and their families in theRepublic of IrelandSeptember 2019

Key Findings2 One in four children with an intellectual disability or developmental disability suchas autism has been put on short school days. This figure excludes children beingput on short school days only at the start of junior-infants class to help easethem into primary education. Half of the children put on short school days had that reduction for 20 days ormore, with many suspensions extending to years without a medical reason andagainst their parents’ wishes. This is likely to represent thousands of childrenaround the country. Many children on short school days are missing certain subjects partially or entirelyand are thus being denied their legal right to education. Most of these arrangements for short school days were made on the basis of achild’s ‘challenging behaviour’ and without consulting experts outside theschool. Children whose diagnosis includes autism are more likely than other children withdisabilities to experience short school days – nearly one in three. Short school days are prevalent across many diagnoses and across all schoolsettings, mainstream and special. As a result of experiencing short school days, children suffer significant feelingsof anxiety and exclusion, and in many cases a desire to leave school entirely. As a result of short school days for their children, parents suffer mental andphysical health problems, including loss of sleep, and a quarter have soughtprofessional help from doctors and/or therapists for themselves. The financial impacts of shortened school days on families are often dramatic andlong-lasting. Some schools take advantage of their relative autonomy in the Irish system toavoid their obligation to educate children with disabilities. Fully 84% of parents of children with disabilities believe that their children do notget the therapies that they need due to long waiting lists or unfilled positions. The State has failed to exercise its authority to prevent an abuse of power bymany schools, which are excluding children in a hidden manner by placing themon short school days.

Education,Behaviourand ExclusionThe experience and impact ofshort school days on children withdisabilities and their familiesin the Republic of IrelandA collaborative research project between Inclusion Ireland and Technological University Dublin,funded under the Irish Research Council’s New Foundations schemeDeborah Brennan, School of Multidisciplinary Technologies and Centre for Critical MediaLiteracy, Technological University DublinHarry Browne, School of Media and Centre for Critical Media Literacy,Technological University Dublin

Table of ContentsKey Findings . 2Easy to read summary. 5Part I: Context and Methodology . 71. Context of Study . 72. Methodology . 9Part II: Main Findings . 123. Data on Short School Days . 124. Impact of Short School Days on Children and Families . 18Part III: Discussion. 235. Understanding the Data in the School Context . 236. Understanding ‘Behaviour’ . 257. The Relevance of Diagnosis . 278. The Relevance of School Setting . 289. Failure of Supports . 3010. Discussion of Impacts . 31Part IV: Conclusion and Recommendations . 3311. Conclusion . 3312. Recommendations . 34List of FiguresFigure 1 Incidence of short school day by group . 12Figure 2 Number of hours child attended school each day . 13Figure 3 Duration and frequency of short school days . 13Figure 4 Whose idea was a short school day starting in junior-infants class? . 14Figure 5 Reasons given by school for short school days . 15Figure 6 Proportion of parents who felt under pressure to agree with short school days . 15Figure 7 Where behaviour was given as reason for short school days, was NEPS consulted?. 16Figure 8 Behaviour-related incidents that led to short school days . 16Figure 9 Where behaviour was given as a reason for short school days, was a behaviourmanagement plan put in place?. 16Figure 10 "My child did not get some of the therapies she/he needs because the waiting listis too long or there is no therapist available." . 17Figure 11 Proportion of parents required by school to be available to pick up childthroughout the school day . 17Figure 12 Summary of family impacts of short school days . 18Figure 13 Indicators of inclusion and belonging for children who have and have notexperienced short school days . 18Figure 14 Did child consistently miss one or more school subjects while on short school days? . 19Figure 15 Positive and adverse effects of short school days on children . 19Figure 16 Levels of stress on parents caused by short school days . 20Figure 17 Health (including mental health) impacts of short school days . 20Figure 18 Impacts on work and career as a direct result of short school days,either or both parents . 21Figure 19 Were family finances impacted by short school days? . 21Figure 20 Percentage of family earnings lost due to short school days. 21Figure 21 Duration of family earnings lost due to short school days . 214

Easy to read summaryThis report is about the educational experiences ofchildren with disabilities and their families in the Republicof Ireland.The research was carried out by Technological UniversityDublin and Inclusion Ireland.The research involved an on-line survey and interviews.393 parents of school-aged children from all over Irelandanswered the survey.The Findings – what we found outShort school days are when children are not allowed tostay in school for the full day. They get sent home early.Short school days are a widely used hidden, often illegalsuspension that is not recorded.Short school days happen in mainstream classes, specialclasses, autism units and special schools.1 in 4 children with a disability have been put on shortschool days.Children who are autistic are more likely to experienceshort school days.Half of these children were on short school days thatlasted for 20 days or more.Most children were on short school days because of‘behaviour’ without experts like NEPS (NationalEducational Psychology Service) being consulted.The Government has failed to prevent abuse of power byschools against children with disabilities in the educationsystem.55

Children on short school days sometimes: Feel sad and worried. Feel lonely and left out. Don’t want to go to school at all because of it. Don’t get a chance to do activities that wouldmake them feel part of the school. Don’t get therapy services that happen in school.Parents are affected by: Having to be ‘on-call’, ready to pick up theirchildren early. Feeling ‘extremely stressful’ with mental andphysical health being affected. Having difficulties at work, having to reduce theirworking hours and, in some cases, having to giveup their jobs. Suffering a huge loss of earnings, often lastingyears.RecommendationsParents and schools should be given information abouttheir rights and guidance on what to do when facedwith a short school day for their child.Parents, NEPS and other relevant services should beinvolved before any decision to reduce a child’s schoolday is made.Schools should name short school days as‘suspensions’, and tell Educational Welfare Officers.This will allow parents to appeal and report to theDepartment of Education.6

Part I: Context and Methodology1. Context of StudyAll children, including those with disabilities, are legally entitled to an education. In 2004, theEducation for Persons with Special Education Needs (EPSEN) Act became the law in Ireland,1and in 2018 this State ratified the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons withDisabilities (UNCRPD) – becoming the last country in Europe to do so.Therefore the law provides that “people with disabilities shall have the same right to avail of,and benefit from, appropriate education as do their peers who do not have disabilities”. Itstates that schools and other education providers must offer “reasonable accommodation andindividualised support” to ensure that children with disabilities get free and inclusive educationin their own communities at all levels, to give them the maximum academic and socialdevelopment and skills “to the level of their capacity”.2 For parents of children with disabilities,the EPSEN Act also provides various means for consultation about their children’s education.The UN has said that UNCRPD requires states to provide “a consistent framework for theidentification, assessment and support required to enable children with disabilities to flourish ininclusive learning environments”3.The EPSEN Act not only promises educational equality, but based on its wording, the State’slegal priority is to deliver that education in integrated mainstream settings – with special unitsand special schools provided where the child’s educational needs require them.Short school days may be justified, for example, by a child’s medical needs, as certified by apaediatrician based in the child’s disability services. Otherwise, the guidelines for schoolspublished by the National Educational Welfare Board are clear in stating that a shortenedschool day is a form of suspension that can only be imposed by a school’s board ofmanagement, or by the principal with the board’s written authorisation. Even where a principalis so authorised, boards of management are, in addition, required to authorise suspensions(including shortening of school days) that last longer than three days, and advised to limitsuspensions to 10 days or under; where a suspension or series of suspensions adds up to 20days in a given school year, parents or guardians must be formally informed of their right toappeal the suspension to the Department of Education under Section 29 of the Education Act1998.4 In addition, suspensions of six consecutive days or more should be referred to anEducational Welfare Officer.1Houses of the Oireachtas, ‘Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act 2004 – No. 30 of2004 – Houses of the Oireachtas’ (2003), he quote on “reasonable accommodation”, an undefined and much-debated term, is from UnitedNations, Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UN, 2008). Other quotes are from Housesof the Oireachtas, Education for Persons with Special Educational Needs Act 2004 – No. 30 of 2004 –Houses of the Oireachtas.3UN Committee on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (CRPD), ‘General Comment No. 4 (2016),Article 24: Right to Inclusive Education’, 2 September .4National Educational Welfare Board, Developing a Code of Behaviour: Guidelines for Schools (Dublin:National Educational Welfare Board, 2008).7

Data has recently been published indicating that 384 children are receiving grants for hometuition.5 It is worth noting in this context that children who are suspended from school or onshort school days are not eligible for these grants and thus not captured in that figure.There is some argument that reductions in school timetables may be justified as part of a planfor certain children with intellectual disabilities and developmental disabilities such as autism –for example, when starting in junior-infants class to provide a more positive experience forchildren entering into the new setting of primary school.In 2019 the Joint Oireachtas Education Committee held hearings to investigate the use of‘reduced timetables’ (i.e. short school days) in Irish education, with submissions and testimonyfrom a variety of stakeholders. Concluding in its interim report on the subject that “in somecases, the use of reduced timetables may not be solely child centred”, the committeerecommended a number of improvements in guidelines for and reporting of reducedtimetables, and in access to therapeutic services to help avoid them.6Also earlier this year, Minister for Education Joe McHugh, in answering a parliamentaryquestion, made it clear that the State recognises a child’s “right to a full school day”. Shortschool days, he said, should be seen as “exceptional” or “transitionary” arrangements. Hepromised that the Schools Inspectorate “intends to challenge the inappropriate use of reducedtimetables in the context of the school inspection process” and that short school days shouldnot be used as a behavioural-management technique.7The Minister’s choice to pivot from a question about short school days to an answer aboutbehaviour management acknowledged a reality that was also visible in the hearings conductedby the committee, where advocates of ‘reduced timetables’ justified their use because of somechildren’s behaviour. While it may be the case that many issues in education and disability arereducible to resources, and the need for more of them, it is not possible to understand andaddress questions about short school days without also seeking to learn more about how andwhy ‘challenging behaviour’ presents itself, and is addressed, in the school system.The Minister for Education said the National Educational Psychology Service (NEPS) should beconsulted rather than short school days imposed when dealing with behaviour. However, NEPSand other outside services are presented as an intervention of last resort in Department ofEducation and Skills guidelines and resource packs on both ‘special educational needs’ and‘behavioural, social and emotional difficulties’, involving ‘Level 3’ escalation – what thedocuments call ‘School Support Plus’.8 Our research examines the extent to which short schooldays are put in place when a behaviour issue would potentially warrant such intervention byNEPS or other outside services instead.In general, it must be noted, the education system here and elsewhere lacks clarity aboutbehaviour and how to deal with it. Globally, ‘challenging behaviour’ is a key issue confronting5Carl O’Brien, ‘Hundreds of Children with Autism, Special Needs without Appropriate School Places’, TheIrish Times, 24 August 2019, opriate-school-places-1.3995648.6Houses of the Oireachtas Joint Committee on Education and Skills, ‘Interim Report on the Committee’sExamination on the Current Use of Reduced Timetables’, June ittee/dail/32/joint committee on education and skills/reports/2019/2019-07-04 he-current-use-of-reducedtimetables en.pdf.7‘Special Educational Needs Service.: 7 Mar 2019: Written Answers’, accessed 10 May 2019,https://www.kildarestreet.com/wrans/?id 2019-03-07a.268.8‘Resources & Publications’, Department of Education and Skills, accessed 25 August eNEPS-/Resources-Publications.html.8

schools.9 In the United States it is estimated that up to 50% of teachers’ and administrators’time is spent addressing issues related to problem behaviour,10 while the OECD found thatnearly one in three teachers cited losing ‘quite a lot of time’ due to behavioural problems inschools.11 The UK Schools Inspectorate, OFSTED, has concluded that “Defining challengingbehaviour [ ] has always been an unsatisfactory enterprise.”12 Researchers who recentlyreviewed the international academic and professional literature on ‘challenging behaviour’ inschools wrote: “There is no commonly agreed definition and there is often very thin analysisof what actually becomes disturbed, challenged, or problematised in such instances.”13 Thislack of interrogation of what we mean when we cite ‘behaviour’ not only obstructs the searchfor root causes, it is a block to developing meaningful policy and practice.14However, even with the best support and monitoring structures and policies in place, theDepartment of Education and Skills would still face limits on its power to deal with behaviouralissues and create an integrated system for educating all children, including those withdisabilities. The Irish education system has long been seen as “a private system funded by thestate”.15 Most authority and responsibility over education is vested in individual schools, theirprincipals and their boards of management, rather than in a central authority.2. MethodologyThis research project, which received ethical approval from Technological University Dublin,employed a mixed methodology of in-depth interviews and an online survey. Interviews with12 parents of children who had experienced short school days were carried out in June, Julyand August of 2019, as well as interviews with three relevant professionals; recordings of theinterviews were later examined for detail and patterns were identified through a process ofthematic analysis.Data presented here was collected via an online survey titled ‘Education and Disability’,between June 17th 2019 and August 14th 2019 (for readability, simply referred to as ‘thesurvey’ throughout the rest of this document). The survey was promoted on social media by9Maija Lanas and Kristiina Brunila, ‘Bad Behaviour in School: A Discursive Approach’, British Journal ofSociology of Education 40, no. 5 (4 July 2019): 1052; Vesa Närhi et al., ‘Reducing Disruptive Behavioursand Improving Learning Climates with Class-Wide Positive Behaviour Support in Middle Schools’,European Journal of Special Needs Education 30, no. 2 (3 April 2015): 913; Anna M Sullivan et al., ‘Punish Them or Engage Them?Teachers’ Views of Unproductive Student Behaviours in the Classroom’, Australian Journal of TeacherEducation 39, no. 6 (1 June 2014), https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2014v39n6.6.10John W. Mckenna and Andrea Flower, ‘Get Them Back on Track: Use of the Good Behavior Game toImprove Student Behavior’, Beyond Behavior 23, no. 2 (1 April 2014): .11OECD, ‘A Teachers’ Guide to TALIS 2013: Teaching and Learning International Survey,’ Text (TALIS,OECD Publishing, 2014), -guide-to-talis2013 9789264216075-en.12John Visser, ‘A Study of Children and Young People Who Present Challenging Behaviour’ (University ofBirmingham School of Education, 2013), -behaviour/r/a11G00000017tcxIAA.13Lanas and Brunila, ‘Bad Behaviour in School’.14A section of this report is devoted to analysing and contextualising our findings in relation to‘behaviour’.15Charlie Lennon and John White, ‘The Reform of School Governance in the Republic of Ireland’, PhiDelta Kappan 78, no. 8 (April 1997): 632–34.9

Inclusion Ireland, Down Syndrome Ireland and other disability groups and organisations. Theterm “short school days” was not used in promoting the survey to reduce the likelihood thatrespondents whose children had experienced the phenomenon would be disproportionalityrepresented in its findings. It is recognised, however, that a negative experience concerningtheir children’s education may make it more likely that parents would complete such a survey,bringing a bias to the results. No more than one survey response was accepted from any givendevice to limit the possibility of having more than one response relating to any given childincluded in the research. The statistics presented in this report are based on 393 responses tothe survey, a number equal to at least 0.5% of the school-going population with disabilities.16The 393 responses were selected from a total of 651 responses to the survey; 63 responseswere not included in the research for this report as they concerned children who were outsideschool age or who had not yet started school, and 195 responses were incomplete. Elevenrespondents answered questions for two children with disabilities in their care.Respondents to the survey came from all 26 counties of the Republic of Ireland and wereparents and carers of school-aged children with a broad range of disability diagnoses, thelargest groups being those diagnosed with autism/autistic spectrum disorder (with or withoutintellectual disability), followed by those with intellectual disability as their primary diagnosis.Small numbers of parents of children with physical and/or sensory disabilities, as well aschildren with diagnoses of global developmental delay, dyspraxia, speech delay and otherdisabilities also responded. The distribution of disabilities is a reasonable reflection of therelative prevalence of those diagnoses in the general population, especially in the cases of themore common diagnoses. The ratio of male to female children was 266 to 127, reflecting thehigher number of male children diagnosed with autism compared to female children. Threerespondents either recorded their child’s gender as ‘other’ or did not disclose their child’sgender. All types of school setting (mainstream, special class in a mainstream school, specialschool) were represented in proportions roughly approximating the national distribution forchildren with disabilities. Twenty parents of school-age children who do not now attend schoolalso responded. The reach of the survey in terms of ethnic background was biased towards thesettled white Irish population (89%) and English was the first language of 97% of the childrenconcerned. Socio-economic indicators such as parental educational attainment and homeownership were generally slightly, but not significantly, higher than the national averages.Most of the respondents (95%) to the survey were female parents or caregivers of the childrenconcerned and 15% of respondents were parenting alone.Questions in the survey concerned the diagnoses, education setting, likes/dislikes andbehaviours of the children involved, and details were sought on various exclusions includingofficial and unofficial suspensions. Data on the emotional, health and financial impacts of shortschool days and related suspensions on the respondents and their children were also gathered.Because of the seriousness of these issues and the public debate around them it was decidedto publish early findings of this study at this time. At this early point in the research, we haveconducted an analysis of results based simply on the following categories: the entire groupsurveyed, school setting (mainstream, special class or unit in a mainstream school or specialschool); school level (primary or secondary); gender; and sometimes by diagnosis (autismspectrum disorder and intellectual disability).The number of responses to each question varies because respondents were not required toanswer most of the questions in the survey – they could choose to skip questions theypreferred not to answer. Where the number of responses to a particular question is largeenough to be of statistical significance (100 or more), we present numbers as percentages. For16‘Disability - CSO - Central Statistics Office’, accessed 28 August /ep/p-cp9hdc/p8hdc/p9d/.10

smaller numbers, we present the number as a fraction. If the number of responses to a binary(yes/no) question is significantly large, we offer a confidence interval (CI) of 95% with amargin of error of 5%, except in relation to the incidence of short school days for girls, wherethe margin of error is 6%. The confidence interval is an estimate of the precision of resultsobtained from our sample compared with the true population, and is calculated here using theWilson Method.17For example, when we say that “24% of school-aged children with disabilities in Ireland havealready experienced short school days”, it means that we are 95% sure that the likelihood thatany child in the general population of school-going children with disabilities has alreadyexperienced short school days is 24% /- 5%. In other words, between 19% and 29%.Interview subjects were recruited separately from survey respondents. Fifteen people wereinterviewed in total, including three professionals in the field. They were mainly recruitedthrough networks already established by Inclusion Ireland for parents who have been affectedby the issues being investigated in the study. Themes for the semi-structured interviews wereinclusion in academic and social aspects of school for children with disabilities; experiences ofadapted curricula; experiences of inclusion and exclusion in day-to-day school activities; andimpacts, if any, of short school days on family life, including finances. Interview subjects wereafforded anonymity for the purposes of this report, though not all of them asked for it. Of theten cases that are highlighted in boxes throughout this report, eight are drawn from interviewsand two come from information given by respondents to the online survey.This research, funded under the Irish Research Council’s New Foundations scheme, was carriedout by academic staff from Technological University Dublin and participatory researchers withintellectual disabilities as part of Inclusion Ireland’s Certificate Programme in Research byApprenticeship. The research was advised and reviewed by a Research Advisory Committeeconvened by Inclusion Ireland; the membership of both the research team and the committeeare presented at the end of the report.17Alan Agresti and Brent A. Coull, ‘Approximate Is Better than “Exact” for Interval Estimation of BinomialProportions’, The American Statistician 52, no. 2 (1 May 1998): 80550.11

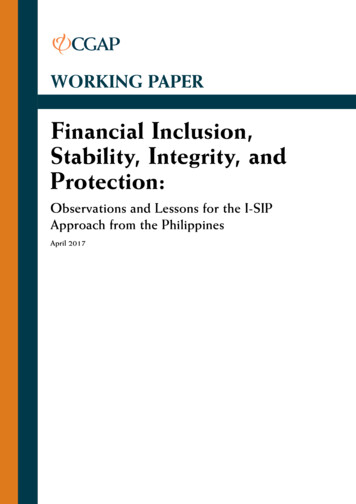

Part II: Main Findings3. Data on Short School DaysThis report documents the level of experience of short school days, and their impact, forchildren with disabilities and their families. The research also gathers data about the durationof short school days, about the rationales offered for them, the procedures through which theywere recommended and enacted, and whether services such as the National EducationalPsychology Service (NEPS) were consulted.18Incidence of short school days by group393 cases (%)All children withdisabilities24%Boys27%Girls17%Children withautism/ASD32%0%5%10%15%20%25%30%35%Figure 1The survey (Figure 1) indicates that, according to their parents, 24% of school-age childrenwith disabilities have already experienced short school days for at least some part of theireducation, with or without parental approval. Where boys alone are considered, the figure is27%; the figure for girls alone is 17%; and where the child’s diagnosis includes autism, it is32%. These figures do not include shorter school days at the beginning of the first year ofprimary school (junior infants), which are discussed below.The children whose parents answered the survey covered the full school-age range (four to 18years old), with 61% being of primary-school age. Responses to the survey suggest that shortschool days are likely to affect considerably more than one in four children with disabilitiesover the course of their entire time in the education system – i.e. that some of those who didnot report short school days in the survey will face them later, because the likelihood of havingexperienced short school days increases with age, with relative peaks observed within thesurvey data at about seven-to-eight years old, and again at 11-to-12 years old and 14-15years old. The number of responses to the survey was too small to establish a predictivepattern. Based on CSO data on sc

Education, Behaviour and Exclusion The experience and impact of short school days on children with d