Transcription

Rationalist Explanations for WarAuthor(s): James D. FearonSource: International Organization, Vol. 49, No. 3 (Summer, 1995), pp. 379-414Published by: The MIT PressStable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/2706903 .Accessed: 24/10/2013 18:45Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at ms.jsp.JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range ofcontent in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new formsof scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact support@jstor.org.The MIT Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to InternationalOrganization.http://www.jstor.orgThis content downloaded from 171.65.249.4 on Thu, 24 Oct 2013 18:45:09 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

RationalistexplanationsforwarJamesD. nwestudyit,is thatwarsare costlybutnonethelessto andstateleadersin particular)are sometimesor alwaysirrational.Theyare subjecttobiases and pathologiesthatlead themto neglectthe costs of war or itsbutdo notpaythecosts,whicharesufferedby soldiersand citizens.Third,one can arguethateven rationalleaders who considerthe risksand costs of war may end up fthethirdsort,whichI ationsaboundin the literatureon internationalconflict,a over,tworeasonsmanyscholarshavegivenrationalista d ftenhaveconcludedthatwarcanbe a rationalalternativeforparticularleaderswho are actingin theirstates'interest-theyfindthatthe sofwarsometimesoutweighAn earlierversionof thisarticlewas presentedat the annual meetingsof D.C., 2-5 September1993.The articledrawsinparton chapter1ofJamesD. Fearon,"Threatsto Use Force: CostlySignalsand Bargainingin InternationalCrises,"Ph.D. diss.,Universityof California,Berkeley,1992. Financial supportof the Instituteon Globalof Californiais gratefullyConflictand Cooperationof the Universityacknowledged.For valuablecommentsI thankEddie Dekel, Eric Gartzke,AtsushiIshida,AndrewKydd,David Laitin,AndrewMoravcsik,James Morrow,Randolph Siverson,Daniel Verdier, Stephen Walt and especiallyCharlesGlaser and JackLevy.1. Of course, argumentsof the second sort may and oftendo presume rationalbehaviorbyindividualleaders; that is, war may be rationalforcivilianor militaryleaders if theywill enjoyvariousbenefitsof war withoutsufferingcosts imposed on the population.While I believe that"second-image"mechanismsof this sort are veryimportantempirically,I do not explore themhere. A more accurate label for the subject of the article mightbe "rational unitary-actorexplanations,"butthisis cumbersome.InternationalOrganization49, 3, Summer1995,pp. 379-414r 1995byThe 10 Foundationand the MassachusettsInstituteofTechnologyThis content downloaded from 171.65.249.4 on Thu, 24 Oct 2013 18:45:09 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

380 InternationalOrganizationthismaybe. Second, the dominantparadigmin internationalrelationstheory,neorealism,is thoughtto advance or even to depend on rationalistargumentsabout the causes of war. Indeed, if no rationalistexplanationfor war istheoreticallyor empiricallytenable,thenneitheris neorealism.The causes ofwar would thenlie in the defectsof humannatureor particularstatesratherthanin the internationalsystem,as arguedbyneorealists.What I referto hereas "rationalistexplanationsforwar" could just as well be called "neorealistexplanations."2This article attemptsto provide a clear statementof what a rationalistexplanationforwaris and to t are both theoreticallycoherentand empiricallyplausible. It should beobviousthatthistheoreticalexercisemusttakeplace priorto testingrationalistexplanationsagainst alternatives-we cannot performsuch tests unless weknow what a rationalistexplanationreallyis. Arguably,the exercise is alsofoundationalforneorealism.Despite itsprominence,neorealisttheorylacks aclearlystatedand fullyconceivedexplanationforwar.As I willarguebelow,itis not enoughto say r that anarchyforcesstates to rely on self-help,which engendersmutualsuspicionand (throughspiralsor thesecuritydilemma)armedconflict.Neitherdo diversereferencesto miscalculation,deterrencefailurebecause of inadequate forcesor incrediblethreats,preventiveand preemptiveconsiderations,in alliancesamountto theoreticallycoherentrationalistexplanaor free-ridingtionsforwar.My main argumentis that on close inspection none of the principalrationalistargumentsadvanced in the literatureholds up as an explanationbecause none addressesor adequatelyresolvesthecentralpuzzle,namely,thatwar is costlyand risky,so rational states should have incentivesto locatethatall wouldpreferto thegambleofwar.The alistargumentsis thattheyfaileitherto addressor toexplain adequately what preventsleaders fromreachingex ante (prewar)A coherentrationalistbargainsthatwould avoid the costsand risksoffighting.explanationforwar mustdo morethangivereasonswhyarmedconflictmightappear an attractiveoptionto a rationalleader undersome circumstances-itmustshow whystates are unable to locate an alternativeoutcome thatbothwouldpreferto a fight.To summarizewhat follows,the articlewill considerfiverationalistargumentsaccepted as tenable in the literatureon the causes ofwar. Discussed at2. For the foundingwork of neorealism,see Kenneth Waltz, Theoryof IntemationalPolitics(Reading,Mass.: Addison-Wesley,1979). For examplesof theorizingalongtheselines,see RobertJervis,"CooperationUnder theSecurityDilemma," WorldPolitics30 (January1978),pp. 167-214;Stephen Walt, The Originsof Alliances (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell UniversityPress, 1987); JohnJ.Mearsheimer,"Back to the Future: Instabilityin Europe Afterthe Cold War," InternationalSecurity15 (Summer1990), pp. 5-56; and Charles Glaser, "Realists as Optimists:Cooperationas19 (Winter1994/95),pp. 50-90.SecuritySelf-Help,"InternationalThis content downloaded from 171.65.249.4 on Thu, 24 Oct 2013 18:45:09 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

War 381lengthbelow,these argumentsare giventhe followinglabels: (1) s; (3) rationalpreventivewar; (4)rationalmiscalculationdue to lack of information;and (5) rationalmiscalculation or disagreementabout relative power. I argue that the firstthreeargumentssimplydo not address the questionof whatpreventsstate leadersfrombargainingto a settlementthat would avoid the costs of fighting.Thethefourthand fifthargumentsdo addressquestion, holding that rationalleaders may miss a superiornegotiatedsettlementwhen lack of informationleads them to miscalculaterelativepower or resolve. However, as typicallystated,neitherargumentexplainswhat preventsrationalleaders fromusingdiplomacyor otherformsof communicationto avoid such costlymiscalculations.If these standardargumentsdo not resolvethe puzzle on rationalistterms,whatdoes? I propose thatthereare threedefensibleanswers,whichtake theformof generalmechanisms,or causal logics,thatoperate in a varietyof moreIn rnationalcontexts.3unable to locate a mutuallypreferablenegotiatedsettlementdue to privateto misrepresentinformationabout relativecapabilitiesor resolveand incentivessuch information.Leaders know thingsabout theirmilitarycapabilitiesandwillingnessto fightthatotherstatesdo not know,and in bargainingsituationsin ordertotheycan have incentivesto misrepresentsuch privateinformationgain a betterdeal. I showthatgiventhese incentives,communicationmaynotallow rationalleaders to clarifyrelativepoweror resolvewithoutgeneratingareal riskof war. This is not simplya matterof miscalculationdue to poorinformationbut rather of specificstrategicdynamicsthat result fromthecombinationof asymmetricinformationand incentivesto dissemble.thatbothSecond,rationallyled statesmaybe unable to arrangea settlementwouldpreferto war due to commitmentproblems,situationsin whichmutuallypreferablebargainsare unattainablebecause one or morestateswouldhave anincentiveto renegeon theterms.While anarchy(understoodas the absence ofan authoritycitedas a cause ofwarcapable ofpolicingagreements)is routinelyin theliterature,itis difficulttoto findexplanationsforexactlywhytheinabilitymake commitmentsshould implythatwar will sometimesoccur.That is,whatare the he inabilitytocommitmakesit impossibleforstatesto strikedeals thatwould avoid thecostsof war? I identifythreesuch specificmechanisms,arguingin particularthatpreventivewar between rational states stems froma owthper se.The thirdsortof rationalistexplanationI findless compellingthanthe firsttwo,althoughit is logicallytenable.Statesmightbe unable to locate a peaceful3. The sense of "mechanism"is similarto thatproposedbyElster,althoughsomewhatbroader.See niversityPress, 1993), pp. 1-7; andJonElster,Nutsand BoltsfortheSocial chap. 1.This content downloaded from 171.65.249.4 on Thu, 24 Oct 2013 18:45:09 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

382 ndivisibilityincludeabortionindomesticpoliticsand theproblemofwhichprincesitson in heit mightbe thatnone fallsissueallowsonlya finitenumberof resolutions,withintherangethatbothpreferto fighting.However,theissuesoverwhichare complexand entslinkageswithotherissuestypicallyare possible;and in ssiblesolutionstoa dispute.amonga fixedoftenbebut ctivelycause of thisindivisibilitylies in domesticpoliticaland s.ratherIn thefirstsectionofthearticleI ngiscostly.Usinga simpleformalizationproblemfacedbystatesin conflict,I hatThe secondand costlyfight.genuinelyrationalstateswouldpreferto a tionspowerandresolvemustbe due tfromtheand incentivesto misrepresentcombinationof privateinformationthatinbargaining.In thethirdsection,I discusscommitmentinformationproblemsas lassessplausibilityexamples.I shouldmakeit clearthatI am firsttime.Thewhollyliteratureand theseideas,mixedwithmyriadon thecausesofwaris massive,taskfacingothers,can be foundin it in variousguises.The maintheoreticalstudentsof war is not to add to the alreadylong list of argumentsandbutinsteadto uresintoa coherentfitforguidingresearch.Towardthisend,I amtheoryempiricalat theproblemof explaininghowwarthatwhenone ional,unitarystates,one findsthatthereareorneorealistreallyonlytwowaysto do it.The rst,manydo antquestion-whatpreventsstatesfromlocatinga bargainbothsideswouldprefertoa fight?Theydo notaddressthequestionbecauseitis widelybutincorrectlyofassumedthatrationalstatescan facea situationexistthatbothsideswouldpreferto a war.4no agreementsdeadlock,wherein4. For an influentialexampleof thiscommonassumptionsee Glenn Snyderand Paul onUniversityConflictAmongThis content downloaded from 171.65.249.4 on Thu, 24 Oct 2013 18:45:09 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

War 383Second,therationalistargumentsthatdo addressthequestion-suchas (4)and (5) above-do notgo farenoughin answeringit.Whenfullydeveloped,theyproveto be one of thetwomajormechanismsdevelopedhere,namely,eithera commitmentproblemor a problemarisingfromprivateinformationI willargue,provideand incentivesto misrepresent.Thesetwomechanisms,thefoundationsfora rationalistorneorealisttheoryofwar.The puzzleandpoliticalscientistswhostudywardismissas naivetheviewMosthistoriansthatall warsmustbe unwantedand agreethatwhilea fewwarsmayhavebeen unwantedbytheleaderswho broughtthemabout-WorldWar I is sometimesgivenas anexample-manyor perhapsmostwars were simplywanted.The leadersinvolvedviewedwaras a rsbelievethatwantedwarsareeasilyexplaineda rationalistperspective.Wantedwarsarethoughttobe wouldprefertotheoccurwhenno domholdsthatwhilethissituationmaybe tragic,itis entirelypossiblebetweenstatesled byrationalleaderswhoconsiderthe costsand risksof fighting.Unwantedwars,whichtakeplaceto conflict,aredespitethe existenceof settlementsboth sides preferredthoughttoposemoreofa puzzle,butonethatis resolvableandalsofairlyrare.The smisunderstandsthepuzzleposedbywar.The reasonis thatthestandardconceptionbetweentwotypesof efficiency-exante and expost. Asdoes notdistinguishthenwaris alwaysinefficientexlongas bothsidessuffersomecostsforfighting,post-both sideswouldhavebeen eringis trueevenifthecostsoffightingaresmall,orifone orbothsidesviewedthebenefitsas greaterthanthecosts,sincethereare fightingforitsownsake,as a consumptiongood,thenwaris inefficientexpost.Froma rationalistthecentralpuzzleaboutwaris nowthatwarwillentailsomeexpost inefficiency.benefitstocosts,and eveniftheyexpectoffsettingtheystillhavean incentivestatesina disputeavoidthecosts.The centralquestion,then,is whatprevents5. See, forexamples,GeoffryBlainey,TheCauses of War(New York: Free Press,1973); MichaelHoward,The Causes of Wars(Cambridge,Mass.: HarvardUniversityPress,1983), especiallychap.1; and ArthurStein, WhyNationsCooperate:Circumstanceand Choice in InternationalRelations(Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell UniversityPress, 1990), pp. 60-64. Even the case of World War I iscontested;an importanthistoricalschool argues that thiswas a wanted war. See Fritz Fisher,Aimsin theFirstWorldWar(New York: Norton,1967).Germany'sThis content downloaded from 171.65.249.4 on Thu, 24 Oct 2013 18:45:09 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

384 mentthatavoidsthecoststheyknowwillbe paidexpostiftheygo to war?Givinga drationalistargumentsliteraturedo heState,and War,theanarchicalnatureof the internationalrealmis routinelycitedas a rootcause of orof war. Waltz arguedthatunderanarchy,explanationforthe recurrenceto make and enforcelaw, "war occurswithouta supranationalauthoritytopreventit. Amongstatesas amongmenthereisbecausethereis nothingIn theabsenceof a supremeauthorityno automaticadjustmentof interests.thatconflictswillbe settledbyforce."6thereis thentheconstantpossibilityThe argumenton a fundamentalbetweenfocusesour attentiondifferencedomesticand internationalpolitics.Withina well-orderedstate,organizedviolenceas a strategyis ruledout-or at leastmadeverydangerous-bytheIn internationalpotentialreprisalsof a ythreatenfortheuseofforceno agencycontrast,reprisalto settledisputes.7The claimis thatwithoutwarwillsucha ionforstatesthathaveconflictingWhileI do not doubtthatthe conditionof nd internationalpolitics,and thatanarchythestandardbothfearof and gumentframingis notenoughto explainwhywarsoccurand employed?forceisa costlyoptionregardlessHowexactlydoesthelackofa centralauthoritystatesfrompreventnegotiatingAs it is typicallybothsideswouldpreferto fighting?agreementsstated,thethatanarchyprovidesa rationalistforwar does notargumentexplanationaddressthisquestionandso cy.the securityNeither,it shouldbe added,do relatedargumentsinvokingone state'seffortsthefactthatunderanarchyto makeitselfmoredilemma,securecan rstate6. The quotationis drawnfromKennethWaltz,Man, theState,and War:A TheoreticalAnalysis(New York: ColumbiaUniversityPress,1959),p. 188.7. For a carefulanalysisand critiqueof thisstandardargumenton the differencebetweentheinternationaland domesticarenas, see R. HarrisonWagner,"The Causes of Peace," in Roy A.Licklider,ed., StoppingtheKilling:How Civil WarsEnd (New York: New York UniversityPress,1993),pp. 235-68 and especiallypp. 251-57.This content downloaded from 171.65.249.4 on Thu, 24 Oct 2013 18:45:09 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

War ired,andthosethataretypicallygivendo notenvisionbargaininganddo notaddressthepuzzleofcosts.Consider,forinstance,a spiralscenarioinwhichan insecurestateincreasesitsarms,renderinganotherso ipatedthereactionproducingwar,thenI argueagainstthesebelow.If thefirstbyitselfthisis a wantit,thentheproblemwouldseemto be miscalculationratherthananarchy,andwe needto As RobertJervishasargued,anarchyand thesecuritydilemmamaywellfosterarmsracesand ionalreferencesto argumentsdo ationalstates.10BelowI willarguethatanarchyis indeedimplicatedas a cause ndinsomecases(e.g.,preventivewaroverstrategicIn contrastterritory).to thestandardarguments,however,showinghow anarchyfiguresin a specificmechanismbywhichstates'inabilityto sideswouldpreferunattainable.PreventivewarIt frequentlyis arguedthatifa decliningpowerexpectsitmightbe attackedthena preventivewarin thepresentmaybebya risingpowerin thefuture,rational.Typically,war argumentsdo not considerhowever,preventivewhethertherisingand declininga wouldleave bothsidesbetteroffthana costlyand riskypreventivewarwould.11The incentivesforsucha deal surelyexist.The risingstateshouldnotwanttobe attackedwhileitis relativelyweak,so whatstopsitin thepresentand ateprefernottoattack?Also,ifwaris ouldthedecliningsidespreferto a ?standardanbeingargumentsupposes8. See JohnH. Herz, "Idealist Internationalismand the SecurityDilemma," WorldPolitics2(January1950), pp. 157-80; and Jervis,"CooperationUnder the SecurityDilemma." Anarchyisimplicatedin the securitydilemmaexternalitybythe followinglogic:but foranarchy,statescouldcommitto use weaponsonlyfornonthreatening,defensivepurposes.9. Jervis,"CooperationUnder theSecurityDilemma."10. For an analysisof e AndrewKydd,"The SecurityDilemma,Game Theory,and WorldWar I," paper presentedat theannual meetingof theAmericanPoliticalScience Association,Washington,D.C., 2-5 September1993.11. The mostdeveloped exceptionI knowof is foundin StephenVan Evera, "Causes of War,"Ph.D. diss.,UniversityofCalifornia,Berkeley,1984,pp. 61-64.This content downloaded from 171.65.249.4 on Thu, 24 Oct 2013 18:45:09 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

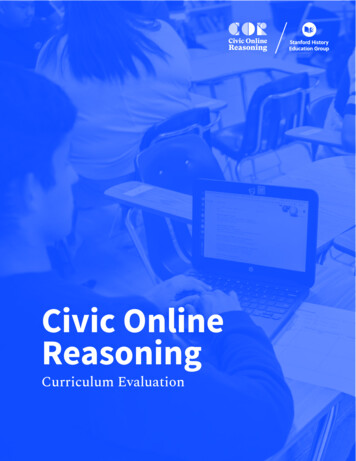

Organization386 n byitselfbe enoughto makewarbutthisisnotso.rational,Positive expected utilityfoundin therationalistexplanationPerhapsthe mostcommoninformalliteratureis thatwar mayoccurwhentwo stateseach estimatethatthetheexpectedcosts.As alizationof thisclaim,war can beMesquitaarguedin an ideshavepositiveexpectedutilityexpectedutilityof war (expectedbenefitsless costs) is greaterthan theatpeace.12ofremainingexpectedutilityfailto addressargumenttypicallyInformalversionsof theexpectedutilityitcanbe ditionsFormalsettlement.bothto preferthecostlygambleofwarto edto avoidthequestionbymakingTo supporttheseclaims,I needto outtheexpectedutilityargument.When will thereexistbargains both sides preferto escouldbothpreferovera set of issuesConsidertwostates,A and B, whohavepreferencesX [0,1]. StateA valto 1, whileB prefersoutcomescloserto 0. Let the states'utilitiesfortheoutcomex E X be uA(x)and UB(1- x), and assumefornow thatUA(-) and UB(O)and weaklyconcave (that is, risk-neutralare continuous,increasing,orWithoutwe can setui(1) 1 andui(0) 0losinganygenerality,risk-averse).wemightthinkofx as representingforbothstates(i A, B). ForconcretenesstheproportionbetweenA andB thatiscontrolledbyA.ofall territorysettlementsthatbothIn orderto saywhetherthesetX containsnegotiateditmustbe oconflict,the militaryoptionversusthoseoutcomes.Almostall analystsof war have12. See Bruce Bueno de Mesquita, The War Trap (New Haven, Conn.: Yale UniversityPress,1981), and "The War Trap Revisited:A Revised Expected UtilityModel," AmericanPoliticalScienceReview79 (March 1985), pp. 157-76. For a generalizationthatintroducesthe idea of abargainingrange, see James D. Morrow,"A Continuous-OutcomeExpected UtilityTheoryofWar," Journalof ConflictResolution29 (September 1985), pp. 473-502. Informalversionsof theFor example,Waltz's statementthat"A statewill useexpectedutilityargumentare everywhere.forceto attainitsgoals if,afterassessingtheprospectsforsuccess,itvalues thosegoals morethanitwaysin a greatmanyworkson war. See Waltz,values thepleasuresof peace" appears in differentMan, theState,and War,p. 60.This content downloaded from 171.65.249.4 on Thu, 24 Oct 2013 18:45:09 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

War 387As valueforwarABargainingrange,.A.A's valueforan outcomexA./o.,,P-CAB's valueforwar,--- AB's valueforan outcomex,.XA.P CBB's favoriteoutcome1A's favoriteoutcomeFIGURE1.Thebargainingrangethatwaris a gamblewhoseoutcomemaybe events.13As Bueno de Mesquitaargued,thismakesa war,expectedutilitya eA prevailswithprobabilitypE mein theissuespace.It followsthatA's expectedutilityforwar ispuA(l) (1 - p)uA(O) - CA,orp - CA,whereCA is stateA's utilityforthecostsofa war.Similarly,stateB's expectedutilityforwarwillbe 1 - p - CB.Sincewe areconsideringrationalisttheoriesforwar,we assumethatCA andCBarebothpositive.Waris thusrepresentedas a andCB lsothevaluetheyplaceonwinningorlosingon theissuesat stake.Thatis,CAreflectsstateA's costsforwarrelativeto anypossiblebenefits.Fora waragainsteachexample,ifthetwostatessee littleto gainfromwinningother,thenCAand CBwouldbe largeevenifneitherside expectedto suffermuchdamageina war.)We can nowanswerthequestionposedabove.The followingresultis easilytheinthelasttwodemonstrated:statedtheregiven g.15settlementsalwaysexistsa setofnegotiatedthereexistsa subsetofX suchthatforeach outcomex in thisset,Formally,UA(X) P - CA and UB(1- x) 1 - p - cB. For example,in the risk-neutralcase whereuA(x) x and UB(1- x) 1 - x, bothstateswillstrictlypreferanyin theintervalThisintervalpeacefulagreement(p - CA,p CB) to fighting.representsthebargaininglevelsrange,withp- CAandp CBas thereservationthatdelimitit.A risk-neutralcase is depictedinFigure1.Thissimplebutimportantresultis worthbelaboringwithsomeintuition.overthedivisionof ncontrasttheycanagreeona splittheycankeepwhattheyagreeto.However,13. See, forclassic examples,Thucydides,ThePeloponnesianWar(New York: ModernLibrary,1951),pp. 45 and 48; and Carl vonClausewitz,On p. 85.14. Bueno de Mesquita,The WarTrap.15. A proofis givenin theAppendix.This content downloaded from 171.65.249.4 on Thu, 24 Oct 2013 18:45:09 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions

388 InternationalOrganizationto the usual economic scenarios,in this internationalrelationsexample theplayersalso have an outsideoption.16For a priceof 20, theycan go to war,inwhichcase each playerhas a 50-percentchanceofwinningthewhole 100.Thisimpliesthattheexpectedvalue ofthewaroptionis 30 (0.5- 100 0.5 0 - 20)for each side, so that if the playersare risk-neutral,then neithershould bewillingto accept less than 30 in the bargaining.But noticethatthereis stillarangeofpeaceful,bargainedoutcomesfrom( 31, 69) to ( 69, 31) thatmakebetteroffthan the war option. Risk aversionwill tend toboth sides eleaderspayno costsforwar,aset of agreementsboth sides preferto a fightwill stillexistprovidedboth arerisk-averseover the issues. In effect,the costs and risksof fightingopen up a"wedge" of bargained solutions that risk-neutralor risk-aversestates willpreferto the gambleof conflict.The existenceof thisex antebargainingrangederivesfromthefactthatwar is inefficientexpost.Three substantiveassumptionsare needed for the result,none of whichseems particularlystrong.First, the states know that there is some truecontest.As discussedbelow,probabilitypthatone statewouldwinin a militaryitcould be thatthestateshave conflictingestimatesofthelikelihoodofvictory,and if both sides are optimisticabout their chances this can obscure thebargainingrange.But even ifthe stateshave privateand conflictingestimatesofwhatwouldhappenin a war,iftheyare rational,theyshouldknowthattherecan be onlyone true probabilitythatone or the otherwill prevail (perhapsfromtheirownestimate).Thus rationalstatesshouldknowthattheredifferentmustin factexista set of agreementsall preferto a fight.overtheSecond, it is assumedthatthe statesare risk-averseor risk-neutralmetric(such asissues.Because riskattitudeis definedrelativeto an underlyingmoneyin economics),the substantivemeaningof thisassumptiondepends onthebargainingcontext.Loosely,it saysthatthestatesprefera fifty-fiftysplitorshareofwhateveris at issue (in whatevermetricit comes,ifany) to a fifty-fiftychance at all or nothing,wherethisrefersto the value of winningor losingawar. In effect,the assumptionmeans thatleaders do not like gamblingwhenthedownsideriskis losingat war,whichseemsplausiblegiventhepresumptionand power.A risk-acceptantthatstateleadersnormallywishto retainterritoryleader is analogous to a compulsivegambler-willingto accept a sequence ofgamblesthat has the expectedoutcome of eliminatingthe state and regime.Even ifwe admittedsucha leader as rational,itseemsdoubtfulthatmanyhaveheld suchpreferences(Hitlerbeinga possibleexception).16. On the theoryof bargainingwith outside options, see Martin J. Osborne and ArielRubinstein,Bargainingand Markets(New York: Academic Press,1990), chap. 3; MottyPerry,"AnExample of Price Formationin BilateralSituations,"Econometrica50 (March 1986), pp. 313-21;ofCalifornia,Berkeley,1993,and RobertPowell,"BargainingintheShadowofPower" (Universitymimeographed).See also the analysesin R. HarrisonWagner,"Peace, War, and the Balance ofPower,"AmericanPoliticalScienceReview88 (September1994), pp. 593-607; and Wagner,"TheCauses ofPeace."This content downloaded from 171.65.249.4 on Thu, 24 Oct 2013 18:45:09 PMAll use subject to JSTOR Ter

war would then lie in the defects of human nature or particular states rather than in the international system, as argued by neorealists. What I refer to here as "rationalist explanations for war" could just as well be called "neorealist explanations."2 This article at