Transcription

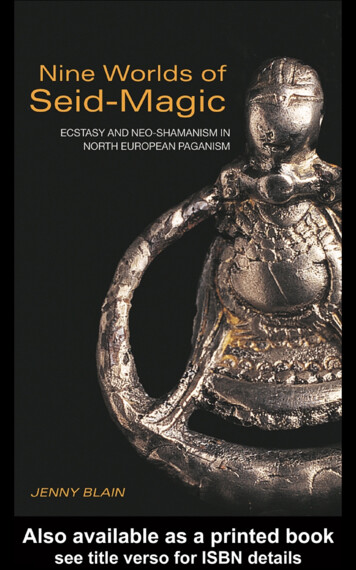

Nine Worlds of Seid-MagicShamanistic practices known as seidr, often involving interactionswith the spirit world and states of altered consciousness, lie at theheart of the pagan religions of Northern Europe. This accessiblestudy explores the ways in which seidr, a key element of ancientScandinavian belief systems described in the Icelandic Sagas andEddas, is now being rediscovered and redeveloped by people aroundthe world. The book draws on a wealth of research and experienceto analyse the phenomenon and place it in context.Written by someone who is a practitioner as well as a scholar,this is a unique exploration of what Northern ‘shamans’ do, andhow they speak of the spirits they meet. It is set within discussionsof shamanism, identity, insider ethnography and new directions inthe anthropology of religion. It will fascinate all those with aninterest in the possibilities for alternative spirituality in today'sworld.Jenny Blain is a senior lecturer in the School of Social Science andLaw at Sheffield Hallam University, where she is route leader for theMA in Social Research Methods.

Nine Worlds of Seid-MagicEcstasy and neo-shamanismin North European paganismJenny BlainLondon and New York

First published 2002by Routledge11 New Fetter Lane, London EC4P 4EESimultaneously published in the USA and Canadaby Routledge29 West 35th Street, New York, NY 10001Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis GroupThis edition published in the Taylor & Francis e-Library, 2004. 2002 Jenny BlainAll rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprintedor reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic,mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafterinvented, including photocopying and recording, or in anyinformation storage or retrieval system, without permissionin writing from the publishers.British Library Cataloguing in Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British LibraryLibrary of Congress Cataloging in Publication DataBlain, Jenny.Nine worlds of seid-magic: ecstasy and neo-shamanism in northernEuropean paganism / Jenny Blain.p. cm.Includes bibliographical references.1. Shamanism–Scandinavia–Miscellanea. I. Title.BF1622.S34 B57 2001293–dc21ISBN 0-203-39833-5 Master e-book ISBNISBN 0-203-39956-0 (Adobe eReader Format)ISBN 0-415-25650-X (hbk)ISBN 0-415-25651-8 (pbk)2001041828

To Marion,who is the future,and to all my Dísir,women of the past

ContentsPrefaceAcknowledgementsixxi1 Introducing shamanism, seidr and self12 The saying of the NornsThe Welling of Wyrd 8Ritual and community 10Cosmology, deities and ‘lore’ 12Seidr or spae? What’s in a name. 15Seidr and shamanism 19Performance or accomplishment? 23Seidr and the anthropologist 2683 The Greenland Seeress: seidr as shamanisticpracticePorbjörg the Seeress 31Seidr in today’s Heathen practice 33The road to Hel’s realm 39Neo-shamanistic seidr 434 Approaching the spiritsThe seer/ess as shamanistic practitioner 47Attaining trance 52Seidr as evil magic? 59Under the cloak 603147

viiiContentsApproaching the spirits 63Seidr as contested practice 715 The journey in the moundNarrating 73Experiencing 75Seeing 76Meeting 78Speaking 80Listening 82Remembering 87736 Re-evaluating the Witch-QueenThe women of the sagas 89Past and present: evaluating the seidwomen 97Heidr, discourse and interpretation 101Women and magic, a continuing strandof practice? 108897 Ergi seidmen, queer transformations?Shamanism and resistance 111The evidence of the sagas 114Men and seidr today 116Many genders or ‘changing ones’? 129Seidr as a Sámi borrowing? 135Queer theory and the ergi seidman 1391118 The dance of the ancestorsSummarising seidr 142Discourses of contested practice 143Reinventing Wyrd 152Shamans and anthropologists 153142NotesBibliographyIndex160166179

ContentsixPrefaceIt’s customary to say something about how one comes to write abook. I do that, in part, in the introductory chapter: it is part of thestory. Here, though, I wish to say something about ‘location’: mine,as author. This is not only a book about a loosely defined spiritualcommunity and its practices, but a product of that community.As researcher/practitioner I occupy one those ‘strange positions’that Marcus (1999: 3) indicates: even more strange because theexperiential communities that I explore are at once ‘exotic’ andpersonal; strange and familiar; with roots deep in Western society,and yet – because they draw directly on those roots, different,‘irrational’ and in many people’s eyes ‘weird’. Or Wyrd. The word isthe same, and implies fate, that which follows, active construction ofobligation and meaning.Next, I am located as a practitioner within the communities Istudy. I am neither an ‘objective’ ethnographer, nor a representativemember. I belong to some organisations, not others; I run workshops and participate in e-mail groups; I hold opinions and includeon my website(s) ‘rants’ about the politics of practice; I amimplicated in the construction of seidr.A word about what I am not. I am neither a linguist or anarchaeologist, but I draw on both disciplines in what follows. I do soboth as practitioner and ethnographer. This book is not only‘about’ seidworkers, it is for seidworkers (among others), and it ismy hope that it may be as valuable (though, doubtless, as disputed)within this community of study as it may be within religious studies,anthropology, or sociology.Finally, a note about some of the words found here: today’s seidfolk draw on the Icelandic literature, and words from that literaturefind their way into their discourse — like ‘seidr’. I have been in

xPrefacesomething of a quandary about transliterating these. The Icelandiccharacters d and p (eth and thorn, pronounced as ‘th’ in ‘there’ and‘thin’, respectively) feature in a number of these words. In the end Ihave adopted the following rule: when the word is used in anIcelandic context, I retain the character. When it is used in anEnglish context, I transliterate using ‘d’ for d, ‘th’ for P. Thus Idescribe Porgeirr the Lawspeaker of the Alping, but my friend’sname is Thorgerd, and a seeress from the old literature maybe referred to as Thurid or Puridr, depending on the context.Exceptions are made where today’s practitioners often retain theletter — most notably in the word ‘seidr’ itself, and often the godname ‘Ódinn’. Seidr, by the way, is pronounced approximately ‘sayth’, with the ‘r’ coming from the Icelandic nominative case (you cansay ‘say-thur’, if you prefer) — alternative versions being noted inchapter 3.With this short note (and with an apology to Icelandic-speakersfor any liberties I take with their language, and especially for anymis-spellings or inaccuracies that my inexpert eye and my languagechallenged Mac’s spelling checker have not caught) I welcome youto a small exploration of the Nine Worlds.

PrefacexiAcknowledgementsMany people have contributed to my construction of this book, inmultiple ways. Not all can be named here. Those to whom I amindebted include the seidworkers that I have seen, and the manyother practitioners of ‘shamanisms’, whether ‘neo-’ or ‘traditional’,with whose work I have engaged.In particular, they include those who gave their stories, their time,their own analysis, trusting me with their experiences. I give gratefulthanks to Winifred, the first person I saw enter the seidworker’sdeep trance, when I felt called to follow; to Diana and the membersof Hrafnar; to Karter and Jordsvin and those others whom I haveseen sit in the ‘High Seat’ or engage with other uses of seidr.Particular mention must be made of Raudhildr, for her ‘seeing’ andfor her friendship, in addition to her narratives of seidr-initiation,her understandings of the ethical issues inherent in performing seidrwithin a community, and her continued discussions of situationsand happenings. Similarly I thank Bil, for sharing his insights.Thanks are due also to those in Nova Scotia, notably Amber,Thorgerd, Erin, Silværina, and Shane; ‘Bride’ who sat in the HighSeat when I needed someone to ‘see’ for me; and all those whoparticipated in our rituals, each of whose questions led me furtheralong my own path. I mention also those for whom I have ‘seen’, orguided in Britain, and the members of the ‘seidrland’ email list.All experiences and discussions with participants, seidworkers,shamans both ‘traditional’ and ‘neo-’, have furthered my understanding. I thank also Jörmundur and other members of Iceland’sÁsatrúarfélagid, who made me welcome and shared their insights.Special thanks go to those who shared their interpretations of‘ergi’ as it applies to their practice: notably Jordsvin, Malcolm, Biland ‘James’, who gave their narratives to the ‘gender paper’;

xiiAcknowledgementsYbjrteir who has added his voice to theirs in this book, and Rod,Gus, Andy, Sifsson, ‘Badger’ and numerous others. In this contextand that of a general sharing of perspectives, and comparison ofapproaches, I owe sincere thanks to Annette Høst, Dave Scott andKaren Kelly. To all who have contributed, your words andexperiences mean much to me, and I hope I have represented themfairly and in the spirit in which they were given. To all those othersimplicit in the construction of those experiences, this book is anoffering.For comments and feedback on chapters, I thank Patrick Buck,Katy Jordan, Karen Kelly, Annette Høst, M.J. Patterson, andRobert Wallis. For permission to quote from material used inseidrtraining and from her own account of ‘initiation’ experiences,and for her support for my work (not least in reading a‘post-modernist’ paper on seidr at the Viking MillenniumSymposium when the authors could not attend) I thank DianaPaxson. A special ‘thank you’ is due, also, to the people athttp://www.snerpa.is/net/netut-e.htm who have created and maintainthe ‘Netutgafan’ website, with Icelandic texts of a wide range ofsagas and other literature: an invaluable resource to all who areinterested in this material. Not least, I acknowledge the financialsupport of the Canadian Social Science and Humanities ResearchCouncil, whose research grant enabled travel and interviewing.Within academia, Graham Harvey has been a constant source ofsupport and encouragement. Many others who have encouraged mywork and supported my analysing seidr as ‘shamanistic’ includeGalina Lindquist, Ronald Hutton, Marion Bowman, and MichaelYork; Fritz Muntean, Shelley Rabinovitch and others of the NatureReligion Scholars’ Network; Robert Adlam, Hope McLean, andothers from the Canadian Anthropology Society; members of theSociety for the Anthropology of Consciousness; and those atnumerous conferences who contributed their questions and theirinsights. Stephan Grundy’s analysis gave me a beginning, and Ithank him and many other specialists, including Britt-MariNäsström, Neil Price, Ingegerd Holland, and Christie Ward, whoanswered my emailed questions.A particular acknowledgement is due to my friend, collaboratorand co-author on various papers, Robert Wallis, with whom thedecision to ‘go public’ as an ‘insider’ engaged in experientialethnography was debated extensively, whom I thank for insights,theoretical discussion and sharing of experience and analysis begun

Acknowledgementsxiiiduring the writing of ‘the gender paper’ and continuing since, andfor permission to quote from his own forthcoming material. In thisbook, I walk a strange path of transformation that winds betweenacademia and the Nine Worlds, through post-modern politics ofneo-shamanic experience. It is good to know that others walk therealso. To other good friends who have provided encouragementduring this endeavour, Arlea and Stormerne, Bill, Cara, Julia, Katy,Ken, MJ, Malcolm, Patrick, members of The Troth, co-workers inCanada and in Britain, and not least to my family in Canada, I sayagain a heartfelt ‘thank you’.Finally, to Roger Thorp and the Routledge editorial staff, thankyou for giving me this opportunity to expand my understandings ofseidr, shamanisms, and multi-sited ethnography in book form, andfor your support and enthusiasm for the project.Jenny BlainHathersage, January 2001

xivAcknowledgementshow will my journey change me? I askedthe seeress, and she replied,seated on Hlidskjalf:‘I cannot see beyond the treesbut they are calling you,only the trees.’

Chapter 1I n t ro d u c i n g s h a m a n i s m ,seidr and selfOn a day at the end of April 1999, I journeyed by plane from NovaScotia to Boston, Massachusetts, on my way further west to Illinois.In Boston I had to perform a particular ritual of transition, challenge and answer, one familiar to many people in today’s Westernworld: going through customs. Why was I entering the UnitedStates? asked the official, and I replied, ‘I’m an anthropologist. Oneof the people I’m studying is getting married. I’m going to dance ather wedding!’.He laughed and waved me on. I walked, musing on the meaningsof the words I’d said, for myself and for the recipient. On the planeI’d been scribbling notes for a paper I had to write, and a futureresearch proposal, and thinking about George Marcus’ discussionsof ‘multi-sited ethnography’ (Marcus 1998). Now here was I, caughtin a maze of meanings, on my way to a wedding, and it wasWalpurgisnacht: Beltane Eve, May Eve.Some years before, I had met Winifred. She was the firstseidworker – she prefers the term 'spae-woman', one who sees whatis to come – that I ever saw in action, and I’d greatly enjoyed thediscussions, in person or email, with her since, as we struggled towork out the disputed territory of seidr, sets of shamanistic practiceof pre-Christian Northern Europe. She had talked of her friendshipwith another Heathen, and then the wedding invitation had arrivedand I made the long trip from Nova Scotia to, indeed, dance at thewedding. But neither the ‘wedding’ nor the ‘dancing’ were likely tobe quite as the customs officer envisaged. The wedding – indeed anexchange of marriage vows – was part of a weekend celebration ofspring, with rituals and a maypole, and the dancing I had in mindwould be that very night, before rather than after the exchange ofvows. There would be drumming, and guests were encouraged to

2Introducing shamanism, seidr and selfdance around the bonfire, to – in the words of Winifred’s invitation– ‘leap, spring and bound’, in honour of the festival: and if they sochose, to dance to honour their animal spirits, taking on the movements of the animal, in a sense becoming the animal, strengtheningspiritual links between the worlds, between human-kind andanimal-kind, masked or unmasked, veiled or unveiled, drawing onand adding to the energies of the night and the fire.Winifred and others like her live between worlds – both theeveryday and shamanic worlds, here the Nine Worlds on the treeYggdrasill. Even within the ‘everyday’ worlds of people, they meet arange of discursive constructions from the rationalism of (much)scientific/discourse to the rationalist tolerance of ‘liberal’ mainstream religion or agnosticism, and from the human-privileging,God-centred discourse of (much) Christian fundamentalism to theEarth-centred focus of (some) Aboriginal groups and the ‘Earth isthe Goddess’ approach of (some) goddess spirituality. Winifred, andothers like her, are emphatically part of Western, society, with itstensions and contradictions. She is therefore making her way, livingher life, within sets of relations and modes of consciousness thatlink her to all these groups and more, at work, in communityendeavours, in attempting to create alliances that further her goalsand those of the Earth that she is, personally, sworn to protect.Less than a month later, I described the incident of the customsofficer, at a conference on folklore with the topic of ‘Going Native’(Blain 2000). Ethnography is changing and the ‘insider’s’ view is nolonger debarred. I was exploring ways to express my experiences,linking the communities of shamanists and seidworkers, andacademics. Two months later I was in Britain, talking with neoshamanic practitioners there about seidr and debating theories ofwhat was ‘shamanism’. So many understandings, so many relationships – and I saw myself within the web of practitioners, connectedto all by strands of Wyrd, fate, history or social construction,positioned in such a way that I could write about these experiencesfor a wider audience. The result is before you now.This book presents an ethnographic exploration of NorthernEuropean shamanistic practice called seidr, within a framework ofrecent theorising of shamanisms and neo-shamanism. Its purposesare those of advancing thinking on neo-shamanisms and theirincreasing relevance within social relations of post-modernity;broadening knowledge of seidr while examining the present-dayconstruction of this specific ‘neo-shamanism’; and dispelling

Introducing shamanism, seidr and self3misconceptions about neo-shamanisms in general (e.g. that they are‘all the same’) and seidr and Northern European ‘reconstructedindigenous’ religious practices in particular. Additionally, the bookexamines the use of experiential anthropology in understanding andtheorising phenomena of altered consciousness and the interactionsof seidworker or ‘shaman’ with their spirit worlds.This therefore is an ethnography of seidr, as it is presently beingrediscovered, even ‘reinvented’, by groups in Europe and NorthAmerica. As such, the book not only describes seidr, its construction and ‘performance’ – a term disputed within practice and theory– and its sources, but engages with debates within and aboutethnography and experiential anthropology.Focusing chiefly on ‘oracular’ or divinatory seidr reconstructedfrom instances in the Icelandic sagas, I locate seidr as ecstaticpractice within specific cultural contexts: Northern Europe of 1,000years ago, though with roots deep in the past, and the WesternEarth-religions revival of the present day. I examine the extent towhich seidr can be said to be either ‘shamanistic’, or ‘shamanic’,understanding the latter term to imply community sanction andstructuring of ecstatic/magical practice (Blain and Wallis 2000). Mywork here is aligned, therefore, with new research within anthropology and religious studies that understands shamanisms, whether‘traditional’, ‘neo-’ or ‘urban’, as historically and culturally specific,at once transforming and themselves in process of transformation,within contexts which are economic, socio-political and spiritual.In chapter 2 I introduce seidr, within a framework of NorthEuropean ‘Heathenry’, and some of the debates surrounding it.Chapter 3 is an exploration of the (re-)construction of oracular,‘high-seat’ or divinatory seidr, the rituals most likely to be metwith by observers. Chapter 4 explores issues of trance states,‘shamanisms’ and ‘the spirits’. Chapter 5 is an experiential narrativeof my introduction to, and exploration of, these relationships. Inchapters 6 and 7, questions of ambiguity, ambivalence, gender,sexuality and the ‘otherness’ of seidworkers – then and now – areexplored, and the final chapter examines some challenges andquestions of magic, neo-shamanisms, rationality, and the locationof myself as ethnographer.Within Western ‘post-modern’ society an increasing number ofpeople are turning to construct their own spiritual relationshipswith the earth, other people, and those with whom we sharethe earth: plants, animals, and various spirit-beings found in the

4Introducing shamanism, seidr and selfmythologies of the world. For many, this goes hand-in-hand with asearch for ‘roots’, authenticity, a quest for meaning that seekers donot find in the hustle and pressures of their fragmented everydaylives. If as Bauman (1997) has suggested ‘post-modern society’ isabout ‘choice’, one of the most obvious examples lies in this questfor located spiritual meaning.There are several ways in which this quest has become manifest:religions, traditions or ‘paths’ often confused by researchers, butdistinct in the discourse of their followers. The ‘new age’ (not dealtwith in this book) focuses, in the main, on self-development,while borrowing from a number of spiritual traditions includingChristianity, Hinduism, Buddhism and various indigenous practicesfrom around the world. Numerous ‘neo-paganisms’ look to aremembered, or invented, past, often romanticised, although anincreasing number of today’s Western Pagans emphasise theirdeliberate construction of religion for today. A third strand is ‘neoshamanism’, also romanticised, which draws heavily on constructions of ‘indigenous’ or ‘traditional’ (world-wide) shamanic practicein the Western literature from the eighteenth century onwards. Seidrcan be envisaged as a point of intersection of these second andthird strands.These ways of relating spiritually to the world have been toooften dismissed by anthropology, sociology or religious studies asirrelevant, either small-scale manifestations of dissatisfaction, oreven adolescent rebellion, teenagers’ attempts to distance themselvesfrom ‘establishment’ of church, state and parents. However, viewedfrom an approach that sees wealth in diversity, and contestation ascreation of meaning, they become part of the patchwork of postmodernity, processes of dynamic construction of present-dayWestern society. Followers of these new/old religious traditions maybe computer programmers, cleaners or clerks, graduates ofseminary education, bartenders or barristers, accountants,archaeologists, teachers, students or systems managers, or evenanthropologists – engaging with social life in many ways, andattempting to blend their spiritual practices with everyday life.My interest in writing this book lies in the intersection ofreconstructed European pre-Christian religion with ‘shamanisms’described from elsewhere, indeed in the overlap or interweaving ofthe second and thirds strand of spiritual thought described above:‘reconstructed’ Paganism, and neo-shamanism. Many descriptionsof neo-shamanisms are available, the most familiar of which is

Introducing shamanism, seidr and self5probably Michael Harner’s (1980) The Way of the Shaman, whichhas become a basic ‘text’ for many practitioners. (For otheraccounts see e.g. Wallis, forthcoming, a.) Constructions of ‘CelticShamanism’ and ‘Norse Shamanism’, as magical practice for today,are increasingly appearing within pagan communities in Europe andNorth America. A number of popular books and magazine articlesdealing with ‘Celtic Shamanism’ (e.g. J. Matthews 1991; C.Matthews 1995; Cowan 1995) have whetted appetites for more, andwhile ‘Norse Shamanism’ or ‘Saxon Shamanism’ – either of whichmight conceivably be called seidr – have received less attention,these too are now attracting notice, particularly through the worldwide web and through Jan Fries’ book Seidways (Fries 1996).Groundwork was laid by Brian Bates’ novel The Way of Wyrd(Bates 1983), which deals with some of the Old English healing‘charms’ within the context of a shaman training an assistant, andhis later non-fiction account The Wisdom of the Wyrd (1996) whichgives as background for shamanistic practice (and for the derivationof his novel) both Old Norse and Old English material.This leads therefore to the ‘North European Paganism’ of thesubtitle (a term which its practitioners are rather unlikely to use, butwhich may make some sense to academics). Under various names,this can be regarded today as a set of linked religious and spiritual‘traditions’ that are being derived by their practitioners fromvarious source texts and archaeological finds. Notably, these sourcesare the Eddas and sagas – the great mediaeval literature of NorthEurope, much of it written in Iceland, popularised/romanticisedduring the nineteenth century and subsequently as ‘NorseMythology’, and most familiar to English-speaking readers in theform of children’s stories. The Eddas and sagas have been fruitfulfields of study for scholars of mediaeval literature, anthropology,history, religious studies, and folklore. They are also assiduouslyscanned (together with Old English texts and other pieces whichmight give clues to pre-Christian spirituality) by practitioners.These latter have a number of names for themselves and what theydo: Ásatrú is the name used in Iceland (see Strmiska 2000) andcommon in North America: other Scandinavian formations of thisterm – literally ‘faith in the gods’, coined as part of the nineteenthcentury romantic movement – include Åsatro, Åsatrú, Asatro. Theadoption of this term in Iceland was for present-day politicalreasons, and many practitioners, there and elsewhere, prefer theterms forn sidr or forn sed, simply ‘the old way’. However, the term

6Introducing shamanism, seidr and selfpreferred by many practitioners in Britain, gaining popularity inNorth America and used by people elsewhere as a descriptor, issimply ‘Heathen’ (heidinn, hedensk), initially used by those whofollowed the ‘new’ religion of Christianity to describe the followersof the ‘old ways’, later becoming a term of abuse, now beingreclaimed by those who have read the mediaeval literature, andthose who refer to the ‘people of the heath’ (Thompson 1998; Cope1998) – suitably for those who would follow the spirits of the land,wherever they may be.So, here, I explore the construction and experience of today’sseidr, as shamanistic practice derived from accounts in the Icelandicsagas. Seidr has a basis within reconstructionist Northern Europeanspiritual communities, and shamanistic groups who adopt methodsand principles derived from shamanisms elsewhere and from coreshamanism (Harner 1980). For an ethnographer of post-modernsociety it is a rich field of study. Its construction is somewhatproblematic, with terms and practices disputed in past and present,and gendered political aspects of its implementation that rapidlybecome apparent where discourses of seidr and seidworkers conflictwith discourses hegemonic in Western societies. In particular, thereare issues around gender and sexuality, and practitioners use theterms of the past within today’s narrative constructions, to recreateor subvert hegemonic practice and to shape new meanings forthemselves and directions for their communities. As culturallyspecific shamanistic, possibly shamanic, practice, seidr positions itspractitioners within the cosmology of the North and North-West ofEurope – the Well of Wyrd and the great tree Yggdrasill – as seekersmove within the Nine Worlds in quest of knowledge from deitiesand ancestors.I write as an anthropologist and as a practitioner. I follow thestrands of seidr practice from present to past, across an ocean andthrough the Nine Worlds of Norse, Northern, or more generally,‘Heathen’ cosmology. In this, what I produce here is a multi-sitedethnography (Marcus 1998), as I explore processes of seidr, frompractitioner to practitioner, community to community, time to time;from spatially located ritual practice and my ethnographer’s tapedinterviews to worldwide email-discussion lists, and through my own,as well as others’, experiences. I write, then, in quest of my ownknowledges, situated by my relation to the practices I discuss: like aseer or shaman, and indeed at time as a seer, I go out into a worldof many levels that is only partly known, and return with

Introducing shamanism, seidr and self7experiences to share. My journey has taken me into possible,disputed, past understandings of being and consciousness,linguistics and comparative religion, mediaeval literature andarchaeology, queer theory and understandings of ‘self ’ and‘meaning’ that slip away, change even as they are examined, as thevision changes when the seeress tries to probe further. On manylevels, therefore, this is a work of experiential anthropology (Goulet1994): observation is not enough to understand relations betweenseidworkers and the spirit world. My own experiences form part ofwhat I analyse, and inevitably position me within the layers ofmeaning that are constructed within the seidr seance and within thecommunities of those who engage with it. Insights within this bookhave been developed in dialogue with many beings. As practitionerand as writer, I engage with worlds and meanings, exploring ways torelate these within the discourses of academia and everyday writing,and by stepping outside these into the language of poetry andimagery. I deal here with current debates within academia andanthropology, on disputed ‘realities’, metaphor and representation,ethnographic theory and methods, ‘shamanism’ as a Westernconstruction of assumed primordial, primaeval, and ‘primitive’religion versus ‘shamanisms’ as creative, contested political andspiritual invention, as well as the multiple realities of theseidworkers.So, like the shaman, I journey out and back, within the culturalcontexts of the discourses of academia and those of seidworkers,and I am transformed by the experience.

Chapter 2T h e s ay i n g o f t h e N o r n sThe Welling of WyrdThey sit, three raised above all others in the room, hands joined:Urdr, who knows all past, and who has direction of this ritual;Werdende who holds the strands that make the present, and tellstheir weaving; centrally Skuld, obligation, asking: ‘do youunderstand me?’ Before them stands Jordsvin, the guide for thisspae-working, who asks ‘is there one here who has a question forthe Norns?’ And one after another, we step forth.We have come here by means of a journey beginning in the barnat Martha’s Orchard, which serves for the great hall of our feastingand assembly at Trothmoot,1 June 1997. We have seen the threewomen move to the high seats, we have heard the song which, in thisspae-working, attunes our consciousnesses to the cosmology of theNorth, the high clear voice of Werdende, the present, the now,singing:Make plain the path to where we areA horn calls clear from o’er the mountainThe gods do gladden from afarAnd mist rises on the meadow .The hounds and eight-legged horse we hearA horn calls c

Nine worlds of seid-magic: ecstasy and neo-shamanism in northern European paganism / Jenny Blain. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references. 1. Shamanism–Scandinavia–Miscellanea. I. Title. BF1622.S34 B57 2001 293–dc21 2001041828 ISBN 0-415-25650-X (hbk) ISBN 0-415-25651-8 (pbk) This editi