Transcription

AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETYDOCUMENTSLymphangioleiomyomatosis Diagnosis and Management:High-Resolution Chest Computed Tomography, Transbronchial LungBiopsy, and Pleural Disease ManagementAn Official American Thoracic Society/Japanese Respiratory Society ClinicalPractice GuidelineNishant Gupta, Geraldine A. Finlay, Robert M. Kotloff, Charlie Strange, Kevin C. Wilson, Lisa R. Young,Angelo M. Taveira-DaSilva, Simon R. Johnson, Vincent Cottin, Steven A. Sahn, Jay H. Ryu, Kuniaki Seyama,Yoshikazu Inoue, Gregory P. Downey, MeiLan K. Han, Thomas V. Colby, Kathryn A. Wikenheiser-Brokamp, Cristopher A. Meyer,Karen Smith, Joel Moss*, and Francis X. McCormack*; on behalf of the ATS Assembly on Clinical ProblemsTHIS OFFICIAL CLINICAL PRACTICE GUIDELINE WAS APPROVED BY THE AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY OCTOBER 2017 AND BY THE JAPANESE RESPIRATORY SOCIETYAUGUST 2017Background: Recommendations regarding key aspectsrelated to the diagnosis and pharmacological treatment oflymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM) were recently published. Wenow provide additional recommendations regarding four specificquestions related to the diagnosis of LAM and management ofpneumothoraces in patients with LAM.Methods: Systematic reviews were performed and then discussedby a multidisciplinary panel. For each intervention, the panelconsidered its confidence in the estimated effects, the balance ofdesirable (i.e., benefits) and undesirable (i.e., harms and burdens)consequences, patient values and preferences, cost, and feasibility.Evidence-based recommendations were then formulated, written, andgraded using the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations, Assessment,Development, and Evaluation) tee e Panel MeetingsResults: For women who have cystic changes on high-resolutioncomputed tomography of the chest characteristic of LAM, but who haveno additional confirmatory features of LAM (i.e., clinical, radiologic, orserologic), the guideline panel made conditional recommendationsagainst making a clinical diagnosis of LAM on the basis of the highresolution computed tomography findings alone and for consideringtransbronchial lung biopsy as a diagnostic tool. The guideline panel alsomade conditional recommendations for offering pleurodesis after aninitial pneumothorax rather than postponing the procedure until thefirst recurrence and against pleurodesis being used as a reason toexclude patients from lung transplantation.Conclusions: Evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosisand treatment of patients with LAM are provided. Frequentreassessment and updating will be needed.Formulating Questions andOutcomesLiterature Search and StudySelectionEvidence SynthesisDevelopment ofRecommendationsManuscript PreparationQuestions and RecommendationsQuestion 1Question 2Question 3Question 4Conclusions*These authors share joint senior authorship.ORCID ID: 0000-0001-9112-1315 (N.G.).Correspondence and requests for reprints should be addressed to Joel Moss, M.D., Ph.D., Cardiovascular and Pulmonary Branch, NHLBI, National Institutes ofHealth, Bethesda, MD 20892. E-mail: mossj@nhlbi.nih.govAm J Respir Crit Care Med Vol 196, Iss 10, pp 1337–1348, Nov 15, 2017Copyright 2017 by the American Thoracic SocietyDOI: 10.1164/rccm.201709-1965STInternet address: www.atsjournals.orgAmerican Thoracic Society Documents1337

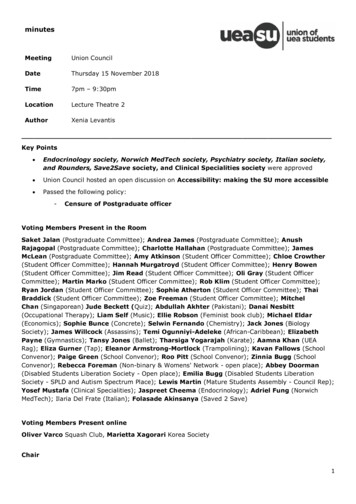

AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY DOCUMENTSOverviewThis guideline is the continuation of a priorlymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM)guideline document developed by theAmerican Thoracic Society (ATS) and theJapanese Respiratory Society (JRS) (1).The current guideline collates the evidencefor emerging advancements in LAM andthen uses this evidence to formulaterecommendations pertaining to thediagnosis and treatment of patients withLAM. The intent of the guideline is toempower clinicians to apply therecommendations in the context of thevalues and preferences of individualpatients and to tailor their decisions to theclinical situation at hand. The guidelinepanel’s recommendations (Table 1) areas follows:dFor patients who have cystic changes onhigh-resolution computed tomography(HRCT) of the chest that arecharacteristic of LAM, but have noadditional confirmatory features ofLAM (i.e., clinical, radiologic, orserologic), we suggest NOT using theHRCT features in isolation to make aclinical diagnosis of LAM (conditionaldrecommendation, low confidence in theestimated effects). Remarks: In the guideline panelists’clinical practices, a clinical diagnosis ofLAM is based on a combination ofcharacteristic HRCT features plus oneor more of the following: presence oftuberous sclerosis complex (TSC),angiomyolipomas, chylous effusions,lymphangioleiomyomas(lymphangiomyomas), or elevatedserum vascular endothelial growthfactor-D (VEGF-D) greater than orequal to 800 pg/ml.When a definitive diagnosis is requiredin patients who have parenchymal cystson HRCT that are characteristic of LAM,but no additional confirmatory featuresof LAM (i.e., clinical, radiologic, orserologic), we suggest a diagnosticapproach that includes transbronchiallung biopsy before a surgical lung biopsy(conditional recommendation, very lowconfidence in the estimated effects). Remarks: The advantage oftransbronchial lung biopsy is that itoffers a less-invasive method to obtainhistopathological confirmation of LAM,as compared with surgical lung biopsy.Although not proven, the panelistsdbelieved that the yield of transbronchiallung biopsy likely correlates withmarkers of parenchymal LAM burden(such as cyst profusion, abnormaldiffusing capacity of the lung for carbonmonoxide, abnormal FEV1) and thatappropriate patient selection is requiredto optimize the safety and efficacy ofthis diagnostic approach. Consultationwith an expert center beforeundertaking transbronchial lung biopsy,combined with a critical review of thetissue specimens by a pathologist withexpertise in LAM, can help avoid falsenegative test results and the need for asurgical lung biopsy.We suggest that patients with LAM beoffered ipsilateral pleurodesis aftertheir initial pneumothorax rather thanwaiting for a recurrent pneumothoraxbefore intervening with a pleuralsymphysis procedure (conditionalrecommendation, very low confidencein the estimated effects). Remarks: This approach is based on thehigh rate of recurrence of spontaneouspneumothoraces in patients with LAM.Nonetheless, the final decision toperform pleurodesis and the type ofpleurodesis (chemical vs. surgical)Table 1. Summary of the Recommendations Provided in This GuidelineContextRecommendationStrength ofRecommendationConfidence inEstimates of EffectHRCT as sole confirmatoryfeature for LAM diagnosisFor patients who have cystic changes on HRCT of thechest that are characteristic of LAM, but have noadditional confirmatory features of LAM (i.e., clinical,radiologic, or serologic), we suggest NOT using theHRCT features in isolation to make a clinicaldiagnosis of LAM.ConditionalLowTransbronchial lung biopsy forhistopathological diagnosis ofLAMWhen a definitive diagnosis is required in patients whohave parenchymal cysts on HRCT that arecharacteristic of LAM, but no additional confirmatoryfeatures of LAM (i.e., clinical, radiologic, orserologic), we suggest a diagnostic approach thatincludes transbronchial lung biopsy before asurgical lung biopsy.ConditionalVery lowPleurodesis after a sentinelpneumothorax to preventrecurrenceWe suggest that patients with LAM be offeredipsilateral pleurodesis after their initialpneumothorax rather than waiting for a recurrentpneumothorax before intervening with a pleuralsymphysis procedure.ConditionalVery lowConditionalVery lowPleurodesis as a contraindication to We suggest that previous unilateral or bilateral pleuralfuture lung transplantprocedures (i.e., pleurodesis or pleurectomy) NOTbe considered a contraindication to lungtransplantation in patients with LAM.Definition of abbreviations: HRCT high-resolution computed tomography; LAM lymphangioleiomyomatosis.1338American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Volume 196 Number 10 November 15 2017

AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY DOCUMENTSdshould be based on shared decisionmaking between the clinician(s) andpatient, after education about variousmanagement options. Every effort mustbe made to ensure that the pleurodesis ishandled by clinicians familiar withmanagement of pleural disease in LAM.We suggest that previous unilateral orbilateral pleural procedures(i.e., pleurodesis or pleurectomy) NOTbe considered a contraindication to lungtransplantation in patients with LAM(conditional recommendation, very lowconfidence in the estimated effects). Remarks: Lung transplantation surgeryin patients with a history of priorpleurodesis can be challenging.Patients who have undergone priorpleural procedures (i.e., pleurodesisor pleurectomy) should be referredto a lung transplant team withexpertise in handling complex pleuraldissections.IntroductionThis guideline is the continuation of a priorlymphangioleiomyomatosis (LAM)guideline document developed by the ATSand JRS (1). The current guidelinecollates pertinent evidence and thenuses this evidence to formulaterecommendations pertaining to thediagnosis and management of LAM. Theseguidelines are not intended to impose astandard of care. They provide the basis forrational decisions in the diagnosis andtreatment of LAM. Clinicians, patients,third-party payers, institutional reviewcommittees, other stakeholders, or thecourts should never view theserecommendations as dictates. Noguidelines or recommendations cantake into account the entire, oftencompelling, individual clinicalcircumstances that guide clinical decisionmaking. Therefore, no one evaluatingclinicians’ actions should attempt toapply the recommendations from theseguidelines by rote or in a blanketfashion. Statements about the underlyingvalues and preferences, as well as qualifyingremarks accompanying eachrecommendation, are integral parts andserve to facilitate more accurateinterpretation; they should never beomitted when quoting or translatingrecommendations from these guidelines.American Thoracic Society DocumentsMethodsCommittee CompositionThe guideline development panel was cochaired by F.X.M and J.M. and consisted ofclinicians and researchers with recognizedexpertise in LAM (1). A methodologist(K.C.W.) with expertise in the guidelinedevelopment process and application of theGrading of Recommendations, Assessment,Development, and Evaluation (GRADE)approach (2) was also a member of thepanel. Patient perspectives were providedby the LAM Foundation (Table 2).panel discussed the scope of the document,the questions to be addressed, the evidence,and the recommendations. Thecosponsoring societies (the ATS and JRS)provided financial support for the meetingsand conference calls, as well as travelexpenses. Additional support for travel ofpanelists to meetings was provided by thenot-for-profit LAM Foundation and LAMTreatment Alliance. The ATS, JRS, andFoundations had no influence on questionselection, evidence synthesis, orrecommendations.Formulating Questions and OutcomesConflict-of-Interest ManagementGuideline panelists disclosed all potentialconflicts of interest according to ATSpolicies. All conflicts of interest weremanaged by the ATS conflict of interest anddocuments departments using theprocedures described in the previousLAM guidelines (1). All seven membersof the writing group were free of conflictsfor all questions related to this version ofthe guidelines.Clinical questions were developed,circulated among the panelists, andrated according to clinical relevance.Patient-important outcomes were selecteda priori for each question and categorizedas critical, important, or not important(3). Patient perspectives on the questionsto be addressed were obtained viaquestionnaires distributed by the LAMFoundation.Literature Search and Study SelectionGuideline Panel MeetingsSeveral face-to-face meetings,conference calls, and e-mail discussionswere held between 2008 and 2017,during which the guideline developmentA detailed description of the search strategywas provided in the recently published LAMguidelines (1). All literature searches wereperformed by a librarian from the NationalInstitute of Health (K.S.), using fourTable 2. Summary of MethodologyMethodPanel assemblyIncluded experts for relevant clinical disciplinesIncluded individuals who represent the views ofpatients and society at largeIncluded a methodologist with appropriate expertise(documented expertise in conducting systematicreviews to identify the evidence base andthe development of evidence-basedrecommendations)Literature reviewPerformed in collaboration with a librarianSearched multiple electronic databasesReviewed reference lists of retrieved articlesEvidence synthesisApplied prespecified inclusion and exclusion criteriaEvaluated studies for sources of biasExplicitly summarized benefits and harmsUsed PRISMA1 to report systematic reviewUsed GRADE to describe quality of evidenceGeneration of recommendationsUsed GRADE to rate the strength ofrecommendationsYesNoXXXXXXXXXXXXDefinition of abbreviations: GRADE Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development, andEvaluation; PRISMA1 Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analysis 1.1339

AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY DOCUMENTSelectronic databases: MEDLINE, EMBASE,Web of Science, and Scopus (Table 2). Theliterature search was originally conductedin 2009, subsequently updated in July 2014,July 2015, and May 2016, and includedstudies published before March 2016. Asmaller working group of seven panelists(C.S., F.X.M., G.A.F., K.C.W., N.G., J.M.,and R.M.K.) reviewed the search results andupdated them as necessary.Evidence SynthesisThe body of evidence for each question wassummarized in collaboration with one of themethodologists (K.C.W.). When possible,data were pooled to derive single estimates.When this was not possible, the range ofresults was reported. The quality of the bodyof evidence was rated using the GRADEapproach (Table 2) (4), as describedpreviously (1).Development of RecommendationsThe guideline development panelformulated recommendations on thebasis of the evidence synthesis, asdescribed previously (1). Recommendationswere formulated by discussion andconsensus; none of the recommendationsrequired voting. The finalrecommendations were reviewed andapproved by all members of the entirepanel.The recommendations were ratedas strong or conditional in accordancewith the GRADE approach. The words“we recommend” indicate that therecommendation is strong, whereasthe words “we suggest” indicate thatthe recommendation is conditional.Table 3 describes the interpretation ofstrong and conditional recommendationsby patients, clinicians, and health carepolicy makers.Manuscript PreparationThe writing group (C.S., F.X.M., G.A.F.,J.M., K.C.W., N.G., and R.M.K.) drafted thefinal guideline document. The manuscriptwas then reviewed by the entire guidelinedevelopment panel, and their feedback wasincorporated into the final draft. Allmembers of the panel have reviewed thefinal version of the document and approveof the document in its entirety.Questions andRecommendationsQuestion 1Should patients be clinically diagnosed withLAM on the basis of their HRCT findingsalone if they have cystic changes in the lungparenchyma that are characteristic of LAMbut have no additional confirmatorycharacteristics of LAM (i.e., clinical,radiologic, or serologic)?Background. The advent of HRCT ofthe chest has transformed the field of diffusecystic lung diseases. A critical review ofHRCT features can often reveal patterns thatare diagnostic in a significant proportion ofpatients with diffuse cystic lung diseases.The characteristic HRCT pattern of LAM isdefined as the presence of multiple, bilateral,uniform, round, thin-walled cysts present ina diffuse distribution. It has been suggestedthat the diagnosis of LAM can be establishedwith a fair degree of certainty on the basis ofthe presence of characteristic HRCT featuresalone (5). However, the rationale forpursuing a definite diagnosis has beenstrengthened of late. A recent randomizedcontrolled trial demonstrated that sirolimusstabilizes lung function decline andimproves quality of life and functionalperformance in patients with LAM (6). Onthe basis of these results, sirolimus is nowU.S. Food and Drug Administrationapproved for treatment of LAM and wasrecommended as the first-line treatmentoption for qualified patients in the previousLAM guideline document (1). However,effective therapy with sirolimus requirescontinuous drug exposure and is associatedwith potential adverse effects. Given thespecter of long-term therapy, it is essentialto have a firm diagnosis before initiatingpharmacotherapy.Summary of the evidence. Oursystematic review identified three studies thatevaluated the performance characteristics ofHRCT of the chest in establishing the diagnosisof LAM in patients with diffuse cystic lungdiseases (7–9). In all three studies, HRCT ofthe chest from patients with various cysticlung diseases were evaluated, and a diagnosiswas rendered by multiple physicians whowere blinded to clinical and histopathologicalinformation. Clinicians included thoracicradiologists (7–9), pulmonologists (9), andpulmonary fellows (9). Diseases includedLAM (7–9), pulmonary Langerhans cellhistiocytosis (7–9), emphysema (7–9),usual interstitial pneumonia (8), lymphoidinterstitial pneumonia (8, 9), desquamativeinterstitial pneumonia (8), Birt-Hogg-Dubésyndrome (9), amyloidosis (9),hypersensitivity pneumonitis (9), nonspecificTable 3. Interpretation of Strong and Conditional Recommendations for StakeholdersImplications forStrong RecommendationConditional RecommendationPatientsMost individuals in this situation would want therecommended course of action, and only a smallproportion would not.The majority of individuals in this situation wouldwant the suggested course of action, but manywould not.CliniciansMost individuals should receive the intervention.Adherence to this recommendation according tothe guideline could be used as a quality criterionor performance indicator. Formal decision aidsare not likely to be needed to help individualsmake decisions consistent with their values andpreferences.Recognize that different choices will be appropriatefor individual patients and that you must help eachpatient arrive at a management decision consistentwith his or her values and preferences. Decisionaids may be useful in helping individuals to makedecisions consistent with their values andpreferences.Policy makersThe recommendation can be adopted as policy inmost situations.Policy making will require substantial debate andinvolvement of various stakeholders.1340American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine Volume 196 Number 10 November 15 2017

AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY DOCUMENTSinterstitial pneumonia (9), lymphangiomatosis(9), and pleuropulmonary blastoma (9). Twostudies included patients without cystic lungdisease as control subjects, including normalvolunteers and patients with noncysticinterstitial lung diseases (7, 9).We pooled the data from all threestudies, which included 72 patients withLAM and 141 patients without LAM. Ouranalysis revealed that expert thoracicradiologists diagnosed LAM on the basis ofHRCT review alone with a sensitivity of87.5% and a specificity of 97.5%, indicating afalse-negative rate of 12.5% and a falsepositive rate of 2.5%. Assuming that 30% ofpatients who present with cystic lung diseaseof unknown etiology have LAM (1) and thatHRCT has a sensitivity and specificity forLAM of approximately 87% and 97%,respectively, then for every 1,000 patientswith cystic lung disease who undergoHRCT of the chest, 261 patients will becorrectly diagnosed with LAM (truepositive results) and 679 patients will becorrectly determined to not have LAM(true-negative results); however, 21 patientswill be incorrectly diagnosed as havingLAM (false-positive results) and 39 patientswill be incorrectly determined to not haveLAM (false-negative results).The guideline panel’s confidence in theestimated sensitivity and specificity was low.The studies appropriately compared theHRCT to a gold standard (histopathology);however, confidence was diminished for tworeasons. First, the studies enrolled neitherconsecutive patients nor patients with truediagnostic uncertainty (potential selectionbias). Second, the results may not begeneralizable to facilities that do not haveaccess to an expert thoracic radiologist tointerpret HRCT (indirectness). Supportingthe importance of the latter limitation, theperformance characteristics of pulmonaryphysicians have been shown to be inferior tothoracic radiologists in being able to diagnoseLAM on the basis of HRCT review (9).Third, the studies did not include allpossible causes of cystic lung disease thatcould mimic LAM, such as metastatictumors, light chain deposition disease, etc.Last, isolated cysts have been reported inotherwise asymptomatic, normal individualsand have been postulated to represent anaging manifestation rather than a truepathological disease process (10, 11).Benefits. The benefit of correctlydiagnosing LAM on the basis of HRCTreview alone is that HRCT of the chest isAmerican Thoracic Society Documentsnoninvasive. If HRCT only could be used tomake the diagnosis of LAM, neithertransbronchial lung biopsy nor surgical lungbiopsy would be required, reducing the riskof complications and the burdens and costsof such procedures.Harms. False-positive results may leadto missed opportunities to treat the correctdisease as well as the adverse effects andcosts of inappropriate treatment ormanagement of LAM.Conclusions and researchopportunities. To recommend clinicaldiagnosis of LAM on the basis ofcharacteristic HRCT findings alone, theguideline panel reasoned that the specificitymust be greater than 95%. The rationale wasto minimize false-positive results, becausesuch results lead to missed opportunities totreat the correct disease as well as theadverse effects and costs of inappropriatetreatment and management of LAM. Thespecificity of HRCT achieved theprespecified threshold; however, the panelwas concerned that the specificity wasmisleadingly high because it was derivedfrom referral institutions with thoracicradiologists who have expertise in interstitiallung diseases and could have beensubstantially lower if the studies had beenconducted in different medical centers. Forthis reason, the guideline panel elected tosuggest not making a clinical diagnosis ofLAM on the basis of HRCT findings alone.The only noninvasive diagnostic testsfor LAM that have been systematicallystudied are HRCT alone and serumVEGF-D. Therefore, research opportunitiesexist to study the sensitivity and specificityof combined findings, such as a HRCT plusclinical features of TSC, angiomyolipoma,chylous effusion, or lymphangioleiomyoma.Recommendation. For patients whohave cystic changes on HRCT of the chestthat are characteristic of LAM, but have noadditional confirmatory features of LAM(i.e., clinical, radiologic, or serologic), wesuggest NOT using the HRCT features inisolation to make a clinical diagnosis ofLAM (conditional recommendation, lowconfidence in the estimated effects).Remarks. In the guideline panelists’clinical practices, a clinical diagnosis ofLAM is based on the combination ofcharacteristic HRCT features plus one ormore of the following: presence of TSC,angiomyolipomas, chylous effusions,lymphangioleiomyomas, or elevated serumVEGF-D greater than or equal to 800 pg/ml(Table 4). In certain cases, such asasymptomatic patients with typical clinicalpresentations for LAM (i.e., young-middleaged, nonsmoking female patients withoutevidence of underlying connective tissuediseases or other features commonly seen incystic lung diseases that can mimic LAM,such as emphysema or Sjögren syndrome)and mild cystic change on HRCT, it may beappropriate to base a probable diagnosis ofLAM on critical review of HRCT alone (5),especially when a definitive diagnosis is notlikely to change management. A secondopinion regarding the diagnosis by anexpert thoracic radiologist can furtherstrengthen confidence in the diagnosis inthese cases. In patients with a probablediagnosis of LAM, the guideline paneliststypically monitor disease progression withserial monitoring of their pulmonaryfunction tests. However, there was generalagreement that a definite diagnosis shouldbe established with one of the additionalcriteria (Table 4) before initiation ofpharmacotherapy with mechanistic targetof rapamycin (mTOR) inhibitors.Values and preferences. Thisrecommendation places a high value onavoiding missed opportunities to treat thecorrect disease, as well as avoiding theadverse effects and costs of inappropriatetreatment of LAM. It places a lower value onthe potential complications, burdens, andcosts of traditional diagnostic testing.Question 2Should patients undergo transbronchial lungbiopsy for the diagnosis of LAM if they havecystic changes that are characteristic of LAMon HRCT of the chest but have noadditional confirmatory characteristics ofLAM (i.e., clinical, radiologic, or serologic)?Background. Typical features onHRCT of the chest can be highly suggestiveof LAM (9). Many experts make a diagnosisof LAM if characteristic cystic lung changeson HRCT are accompanied by thepresence of tuberous sclerosis complex,angiomyolipomas, chylous effusions,lymphangioleiomyomas, or a serum VEGF-Dlevel greater than or equal to 800 pg/ml (5, 12).Although for some patients, such as thosewithout symptoms and a mild cyst burden,a strategy of close monitoring only maybe appropriate, obtaining diagnosticcertainty is the optimal approach in thosewith symptoms or progressive diseasebefore initiating treatment. Video-assistedthoracoscopic surgery (VATS)-guided1341

AMERICAN THORACIC SOCIETY DOCUMENTSTable 4. Diagnostic Criteria for LymphangioleiomyomatosisDefinite LAMDefinite diagnosis of LAM can be established if a patient with compatible clinical history* andcharacteristic HRCT of the chest† has one or more of the following features:1. Presence of TSC‡2. Renal angiomyolipoma(s)x3. Elevated serum VEGF-D 800 pg/ml4. Chylous effusion (pleural or ascites) confirmed by tap and biochemical analysis of thefluid5. Lymphangioleiomyomas (lymphangiomyomas)x6. Demonstration of LAM cells or LAM cell clusters on cytological examination of effusionsor lymph nodesjj7. Histopathological confirmation of LAM by lung biopsy or biopsy of retroperitoneal orpelvic massesDefinition of abbreviations: D2-40 podoplanin; HMB-45 human melanoma black-45; HRCT high-resolution computed tomography; LAM lymphangioleiomyomatosis; mTOR mechanistictarget of rapamycin; TSC tuberous sclerosis complex; VEGF-D vascular endothelial growthfactor-D; VEGFR3 vascular endothelial growth factor receptor 3.The diagnosis of LAM should be established using the least invasive approach (details in Figure 1). In somecases, such as asymptomatic patients with mild cystic change on HRCT, a probable diagnosis of LAMwith serial monitoring may be sufficient, if a definite diagnosis will not change management and somelevel of diagnostic uncertainty is acceptable to the patient and clinician. Every effort must be made toestablish a definite diagnosis of LAM before initiation of pharmacological therapy with mTOR inhibitors.*Compatible clinical history with LAM includes young to middle-aged female patients presenting withworsening dyspnea and/or pneumothorax/chylothorax and the absence of features suggestive ofother cystic lung diseases. Typical clues to an alternative etiology of cystic lung disease on historyinclude the presence of sicca symptoms or an underlying diagnosis of connective tissue disease,significant smoking history, personal/family history of non–TSC-related facial skin lesions, and/orkidney tumors. Most patients with LAM will have an obstructive defect on pulmonary function tests.Some patients, especially early in their disease course, may be asymptomatic and have normalpulmonary function tests.†Characteristic HRCT chest features of LAM include the presence of multiple, bilateral, uniform,round, thin-walled cysts present in a diffuse distribution, often with normal-appearing intervening lungparenchyma.‡Detailed history and physical examination to investigate for the presence of TSC is needed. Thediagnosis of TSC is established based on the proposed criteria in the TSC Guidelines (65). Referral toa TSC specialist may be needed if unsure of the diagnosis.xAngiomyolipoma may be diagnosed on the basis of radiographic appearance of characteristicfat-containing lesions either on computed tomography scan or magnetic resonance imaging. Contrast isnot typically required unless the vascular characteristics of the tumor need to be analyzed, such as forevaluation of the potential for hemorrhage or the planning for embolization. Similarly, lymphangioleiomyomascan typically be diagnosed on the basis of characteristic radiographic appearance.jjLAM cell cluster refers to a spherical aggregate of LAM cells enveloped by a layer of lymphaticendothelial cells that is found in chylous effusions of patients with LAM. The diagnosis of LAM can bebased on typical morphological appearance of LAM cells and positive staining for smooth muscle cellmarkers and HMB-45 by immunohistochemistry. Lymphatic endothelial cells surrounding the LAMcells can be highlighted by positive immunohistochemical staining for lymphatic endothelial cellmarkers, including D2-40 and VEGFR-3.surgical lung biopsy has been consideredthe gold standard for obtaininghistopathological confirmation of LAM;however, small retrospective series suggestthat transbronchial lung biopsy can be safeand effective in a proportion of patientswith suspected LAM.Summary of the evidence. Oursystematic review identified 5 case reports(13–17) and 12 case series (18–29) thatdescribed transbronchial lung biopsy forthe diagnosis of LAM. We did not conside

high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) of the chest that are characteristic of LAM, but have no additional confirmatory features of LAM (i.e., clinical, radiologic, or serologic), we suggest NOT using the HRCT features in isolation to make a clinical diagnosis of LAM (conditional