Transcription

Pharmaceuticals and Life SciencesPharma 2020: Challenging business modelsWhich path will you take?

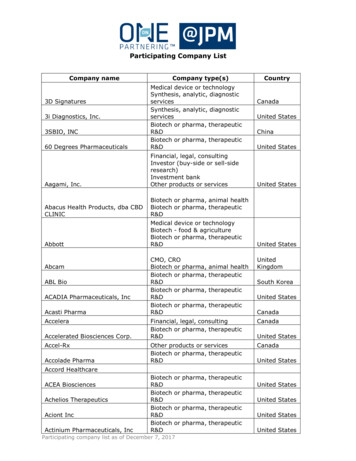

Table of contentsPrevious publications in this series include:PharmaceuticalsPharmaceuticals and Life SciencesPharmaceuticals and Life SciencesPharma 2020: The visionWhich path will you take?*Pharma 2020: Virtual R&DWhich path will you take?Pharma 2020: Marketing the futureWhich path will you take?*connectedthinkingPharma 2020: The vision #Published in June 2007, this paperhighlights a number of issues that willhave a major bearing on the industry by2020. The publication outlines the changeswe believe will best help pharmaceuticalcompanies realise the potential the futureholds to enhance the value they provide toshareholders and society alike.Pharma 2020: Virtual R&D1This report, published in June 2008,explores opportunities to improve the R&Dprocess. It proposes that new technologieswill enable the adoption of virtual R&D; andby operating in a more connected world theindustry, in collaboration with researchers,governments, healthcare payers andproviders, can address the changing needsof society more effectively.Published in February 2009, this paperdiscusses the key forces reshaping thepharmaceutical marketplace, includingthe growing power of healthcare payers,providers and patients, and the changesrequired to create a marketing and salesmodel that is fit for the 21st century. Thesechanges will enable the industry to marketand sell its products more cost-effectively,to create new opportunities and to generategreater customer loyalty across thehealthcare spectrum.“Pharma 2020: Challenging business models” is the fourth paper in the Pharma 2020 series on the future of the pharmaceutical industry to bepublished by PricewaterhouseCoopers. This publication highlights how Pharma’s fully integrated business models may not be the best option for thepharma industry in 2020; more creative collaboration models may be more attractive. This paper also evaluates the advantages and disadvantages ofthe alternative business models and how each stands up against the challenges facing the industry.All these publications are available to download at: www.pwc.com/pharma2020

Table of contentsIntroduction1Profiting alone versus profiting together1Harking back to the future2Reading the signs2Broadening the value proposition and managing the value chain4Choosing between different collaborative models6 The federated model The virtual variant of the federated model The venture variant of the federated model The fully diversified modelCharting a successful Pharma 2020: Challenging business models

Table of contents

IntroductionThe pharmaceutical marketplaceis undergoing huge changes, aswe indicated in “Pharma 2020:The vision”, the White PaperPricewaterhouseCoopers* published inJune 2007.1 These changes will have amajor bearing on the kind of businessmodels pharmaceutical companiesneed to employ.In the following pages, we shall lookat the main trends dictating the needfor a more collaborative approach. Weshall also evaluate the advantages anddisadvantages of the alternative businessmodels and how each stands up againstthe challenges facing the industry.Profiting alone versusprofiting togetherMost Big Pharma companies havetraditionally done everything from researchand development (R&D) through tocommercialisation themselves. But wepredict that, by 2020, this model willno longer work for many organisations.If they are to prosper, they will need toimprove their R&D productivity, reducetheir costs, tap the potential of theemerging economies and switch fromselling medicines to managing outcomes– activities few, if any, companies canaccomplish on their own.Big Pharma’s traditional business modelhinges on the ability to identify promisingnew molecules, test them in large clinicaltrials and promote them with an extensivemarketing and sales presence (seesidebar, What is a business model?). Inthe predominant version of this model, asingle company may employ contractorsto supplement its own efforts, but itseeks to generate profits on its own. Inessence, it pursues what might be calleda “profit alone” path.Even the largest pharmaceuticalcompanies will have to collaborate withother organisations to develop effectivenew medicines more economically,help patients manage their health andensure that the products and servicesthey provide really make a difference.Moreover, they may have to step faroutside the sector to find some of thepartners they need.But, by 2020, the strategy ofsinglehandedly placing big bets on afew molecules, marketing them heavilyand turning them into blockbusters willnot suffice. As J.P. Garnier, former chiefexecutive of GlaxoSmithKline, recentlypointed out, it is a “business modelwhere you are guaranteed to lose yourentire book of business every 10 to12 years”.2We believe that two principal businessmodels – federated and fully diversified– will emerge, as Pharma prepares forthe future. We also think that the currenteconomic downturn will acceleratethe shift to these new models, both byreinforcing one of the key causal factors– the pressure on healthcare payersto maximise the value they get for themoney they spend – and by opening upnew opportunities to build or buy thenetworks that will be required.More importantly still, it is a businessmodel that will no longer meet themarket’s needs. Management guruClay Christensen has convincinglydemonstrated how disruptiveinnovations in various industries havedismantled the prevailing businessmodel, by enabling new players totarget the least profitable customersegments and gradually move upstreamuntil they can satisfy the demands ofevery customer – at which point the oldWhat is a business model?The term “business model” is usedto encompass a wide range of formaland informal descriptions of the coreelements of a business. We haveused the term in the following sense:“A company’s business model is themeans by which it makes a profit –how it addresses its marketplace, theofferings it develops and the businessrelationships it deploys to do so.”business model collapses.3Pharma is currently undergoing justsuch a period of disruptive innovation.By 2020, most medicines will bepaid for on the basis of the resultsthey deliver – and since many factorsinfluence outcomes, this means thatit will have to move into the healthmanagement space, both to preservethe value of its products and to avoidbeing sidelined by new players. If it is tomake groundbreaking new medicinesfor which governments and healthinsurers are prepared to pay premiumprices, it will also have to build therelationships and infrastructure requiredto ensure that it can get access to theoutcomes data they collect.In short, the rules of the game areshifting dramatically. And, as MichaelG. Jacobides, Associate Professor ofStrategic and International Managementat the London Business School, notes,when an entire “industry architecture”is transformed, it is not only “who doeswhat” that changes, it is also “whotakes what”.4By 2020, no pharmaceuticalcompany will be able to “profitalone”. It will, rather, have to “profittogether”, by joining forces with awide range of organisations, from*‘PricewaterhouseCoopers’ refers to the network of member firms of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited, each of which is a separate andindependent legal entity.Pharma 2020: Challenging business models1

Apple’s core strategy ofcollaborationLondon Business School ProfessorMichael G. Jacobides has recentlyargued that successful companies donot compete in a sector; they shapethe nature of a sector. They redefinethe part of the value chain theyoccupy, and keep most of the valueadd through the intelligent design oftheir collaboration with others in thesector.Thus collaboration is not just a toolfor doing the same things moreeffectively. At its most powerful, itcan reshape an entire market, asApple has shown. Apple redefined themobile music sector by outsourcingthe production of the devices andaccessories, while retaining control ofthe iTunes software. In other words,it recognised that it could makemoney by creating and orchestratinga network of relationships – bycontrolling, rather than owning.Apple used three specific tacticsto change the rules of the game. Itenhanced the mobility of the partsof the sector in which it has nopresence, by establishing a smallset of suppliers who know that theycan be replaced at any time. It madeitself into a bottleneck, by holdingonto the music format and ensuringthat files compatible with iPod canonly be played on iPod devices.And it redefined who did what, byencouraging other companies todevelop accessories rather thanentering the accessories marketitself. This has enabled it to benefitfrom the efforts of those that supportits architecture, without making anycapital commitment itself.academic institutions, hospitals andtechnology providers to companiesoffering compliance programmes,nutritional advice, stress management,physiotherapy, exercise facilities, healthscreening and other such services.Harking back to thefutureOf course, some pharmaceuticalcompanies have already tried tocollaborate with other organisations.Rhone-Poulenc Rorer (now part ofsanofi-aventis) created RPR Gencell, theworld’s first biotechnology network, in1994.5 Many of the largest companiesalso established disease managementprogrammes in the 1990s, althoughmost of them were not very successful– primarily because healthcarepayers were sceptical about industrysponsored disease management.6So we are not suggesting that thedifferences between these early effortsand the business models that are likelyto prevail in 2020 will be completelyblack and white. Nevertheless, we thinkthat two key differences will apply.First, the technological and culturalpre-conditions to facilitate collaborationare now in place. In the mid-1990s, theInternet was still in its infancy and manyof the tools that enable collaboration didnot exist. Today, however, such tools areplentiful and the wider business culturehas changed dramatically. IBM, Apple,Amazon and their ilk have demonstratedthe power of open platforms,transformed corporate attitudestowards networking and shown that it ispossible to reap much richer rewards byprofiting together than by profiting alone(see sidebar, Apple’s core strategy ofcollaboration).7Second, by 2020, collaboration2will be a “do or die” requirementfor pharmaceutical companies andhealthcare payers alike. It will beessential for pharmaceutical companiesto develop effective new medicinesand address the demands of payersincreasingly well equipped to measurewhat they are getting for their money;and essential for payers to cope withrapidly escalating healthcare costs.Reading the signsVarious forces are changing theenvironment in which Pharma operatesand the relative positions of the differentplayers in the healthcare arena. Thesetrends all point towards the need formuch greater collaboration (see Figure 1).The global healthcare bill is soaring,as the population ages, new medicalneeds emerge and the disease burdenof the developing world increasinglyresembles that of the developed world.Hence the fact that governmentsand health insurers everywhere arestruggling to contain their expenditure.The issue is further exacerbated by thecurrent economic turmoil that will puteven greater financial pressure on thepayer community.Healthcare payers in the industrialisedeconomies are already mandatingwhat doctors can prescribe. TheBritish National Health Service hasalso introduced a flexible pricingscheme under which the prices ofnew medicines can be lowered orlifted, depending on the outcomesthey deliver.8 And US PresidentBarack Obama’s administration ismoving towards opening up the USmarket to much greater competitionfrom generics, as well as allowing theimportation of cheaper medicationsfrom “safe” countries.9PricewaterhouseCoopers

The developing world will soon comeunder equal pressure. The emergingeconomies will experience the mostrapid growth in demand for medicinesover the next 11 years, but many (if notall) of them will struggle to fund thisdemand. The Chinese government has,for example, undertaken to introducea universal healthcare system with alevel of cover that does not exceedthe country’s current economicdevelopment. However, it is hard to seehow the plan will not entail a substantialincrease in China’s healthcare costs.10Healthcare payers in both thedeveloped and developing worlds arealso beginning to measure outcomesmuch more carefully and to emphasisethe importance of prevention. By 2020,they will expect the industry to go“beyond the medicine” by providingprophylactics and healthcare packagesdesigned to help patients manage theirhealth. Moreover, patients will play amuch bigger role in determining howthey are treated, as the money theyspend on medicines likewise risesand the Internet gives them access tomore information. Armed with insightsFigure 1: The key trends now emerging and their implications for PharmaTrendsMarket trendsHealth and healthcare trendsScientific and technological trends Patients are becoming better informed Patients are picking up a bigger shareof the bill Demand for personalised medicine isincreasing Patients want cures, not treatments The emerging markets are becomingmore important The burden of – and bill for – chronicdisease is soaring Healthcare payers are establishingtreatment protocols Pay-for-performance is on the rise The boundaries between different formsof care are blurring Financial constraints on payers areincreasing R&D is becoming more virtualised The research base is shifting to Asia Remote monitoring is improving rapidlyImplicationsPharma will need to go “beyond themedicine”R&D will need to go beyond the labThe Pharma and healthcare value chainswill become much more intertwined Pharma will be paid for outcomes,not products Outcomes data will drive healthcarepolicy Prevention will gain a higher healthcareprofile Pharma will need to offer “medicineplus” packages of care Pharma will have to adopt more flexiblepricing strategies Pharma will need access to outcomesdata Pharma will have to work withtechnology vendors to virtualise R&D Pharma will need a wider, moremulti-disciplinary skills base Pharma will need to expand itspresence in Asia Pharma will need to demonstrate “real”value-for-money Pharma will have to work more closelywith the regulators Pharma will have to collaborate withpayers and providers to performcontinuous trials Pharma will have to collaborate withnumerous service providers to deliverpackages of careBusiness models based on collaborationSource: PricewaterhouseCoopersPharma 2020: Challenging business models3

Emerging collaborative networksSeveral pharmaceutical firmshave already begun to use morecollaborative models. One suchinstance is Lilly, which is currentlytransforming itself from a traditionalfully integrated pharmaceuticalcompany into a fully integratedpharmaceutical network, so that it candraw on a wide range of resourcesbeyond its own walls. Lilly hopes thatteaming up with other organisationsto create virtual R&D programmeswill enable it to get better access toinnovation, reduce its costs, managerisks more effectively and enhanceits productivity. For example, theChorus Project is a virtual organisationto take molecules quickly to Proofof Concept. Lilly also uses externalnetworks comprising third parties suchas Piramal Life Sciences, HutchisonMediPharma, Suven Life Sciences forthe development of molecules.gleaned from educational websites,discussion groups and blogs, they willnot only want better, safer medicines,they will also want a range of satelliteservices they can tailor to theirindividual needs.If Pharma is to accommodate thesechanges in the marketplace, it will haveto collaborate much more extensively– as it will, indeed, to capitalise onsome of the scientific and technologicaltrends that are now emerging. Theresearch base is shifting, for example.Non-OECD economies accounted for18.4% of the world’s R&D in 2005, upfrom 11.7% in 1996. The number ofpatents filed by Asian researchers alsoincreased significantly over the sameperiod, albeit from low levels.11 So theindustry will have to forge much closerlinks with the most reputable centres ofscientific excellence in these countries.Swiss biopharmaceutical developmentspecialist Debiopharm has pioneered amore radical approach. The companyin-licenses promising new candidatesfrom academic institutes and biotechcompanies, develops them and thenout-licences them to Big Pharma.Debiopharm’s successes include threeproducts with combined global salesof more than US 2.6 billion in 2007.Meanwhile, new technologies areproviding new sources of knowledge.Home surveillance systems, portabledevices and implants, linked to onlineand wireless networks, will facilitatethe monitoring of patients on a realtime basis outside a clinical setting.But if Pharma is to get access to theoutcomes data remote monitoringgenerates, it will have to collaboratewith the hospitals and clinics thatcapture this information.Most of the collaborative models thatcurrently exist are limited to R&D. Butit is easy to envisage various otherpermutations, including networksfocusing on different therapeuticareas and covering everything fromR&D through to sales and marketing;networks focusing on differentenabling technologies, such asgenomics, proteomics and stem cellresearch; and networks focusingon the management of outcomes inspecific patient segments.Technological advances will likewiseenable the virtualisation of large partsof the R&D process, as we explained in“Pharma 2020: Virtual R&D”.12 Some ofthe leading pharmaceutical companiesare already exploring the potential ofsemantic technologies and computeraided molecule design. Variousacademic institutes and bioinformaticsfirms are also building computer modelsof different organs and cells, with theultimate aim of creating a “virtual man”.But developing such a model will require4a monumental collaborative effort farexceeding that required to complete theHuman Genome Project.13The economic case for change isclear. The decline of revenue growthand margins result in reducedshareholder returns which will forcepharmaceutical companies to adapt.There is a compelling case for increasedcollaboration. Delivering drug therapiesto payers and patients in a 2020 worldwill require new skills, technologies andchannels - the infrastructure required willbe uneconomic for anyone, other thanthe largest players, to build internally.To sum up, the key social, economicand technological changes currentlytaking place in the pharmaceutical andhealthcare arena will all necessitate thedevelopment of multinational, multidisciplinary networks drawing on amuch wider range of skills than Pharmaalone can provide. The constraintsthat previously hindered organisationsfrom collaborating over distance aresimultaneously evaporating – paving theway for the use of new business models(see sidebar, Emerging collaborativenetworks).14 In the next sections, we shalllook at the implications of broadening thevalue proposition, the various models thatexist and the different opportunities andrisks they present.Broadening the valueproposition andmanaging the value chainPharma currently creates value bydeveloping new medicines (and arelatively limited number of diagnostics).Collaborating much more closely withthe key stakeholders in the healthcaresector will enable the industry bothto expand its remit and to align itsPricewaterhouseCoopers

on getting access to the patients whomproviders serve and income from thepayers who fund those providers. Yetthe relationship between the differentplayers is often quite antagonistic and,while they continue to clash, they arestruggling to retain their respectivegoals.15value chain more closely with those ofhealthcare payers and providers.As we indicated in more detail in“Pharma 2020: Marketing the future”,the value chains of the three partiesare heavily interdependent. The valuepayers generate depends on thepolicies and practices of the providersthey use. The value providers generatedepends on the revenues payers raiseand the medicines Pharma makes. Andthe value Pharma generates dependsa more dynamic relationship withhealthcare payers and providers. So,too, will building the networks requiredto deliver healthcare packages thatencompass a wide range of productsand services from numerous differentsuppliers. This will ultimately result inthe convergence of the separate, linearvalue chains that exist today and theemergence of a single, circular valuechain (see Figure 2).If Pharma broadens its valueproposition, it can begin to close thegap. Creating feedback loops to captureoutcomes data will help it to establishFigure 2: By 2020, the pharmaceutical, payer and provider value chains will be much more closely intertwinedaM&PayerProviderPharmaanou cetofpocket paymentsReferralillsall Pg & piB rinDevelopmentagemanyong ollisi s, CRa axetingcharesReay m emen nttofhealthRaof f isinginancegetinMark les& Sartsoiumemg prRaisinnDi ufacstrib turinuti gfFonecinroviders’bPatientcarepertiar daryc yaAnalyspopul isatioat ris nkPologic rovalstu isidi onesof,AePronntievreemia&Epidstrinient luations etc.em ic evaag onoman oeccareM acmtermarngphLodmMediPractice guideclines, c al Sliniecal g rvuid icPrimary careanSecec,oTnesofrve eoC tivetc.icesvrseit oon,mtnmeSource: PricewaterhouseCoopersPharma 2020: Challenging business models5

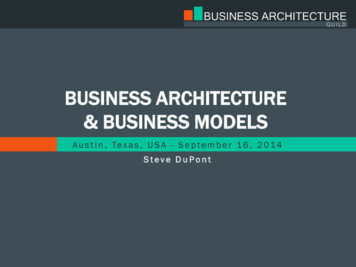

Choosing betweendifferent collaborativemodelsOne vital question remains, however;namely, what sort of model shouldcompanies use to effect these changes?We believe that two principal models– federated and fully diversified – willemerge. We have also identified twovariants of the federated model. In thevirtual version, a company outsourcesmost or all of its activities; in theventure version, it manages a portfolioof investments (see Figure 3). The twomodels are not mutually exclusive. Afully diversified company might chooseto use a federated model for certainaspects of its business, and vice versa.But we think that the federated modelwill ultimately dominate, primarilybecause it is quicker and moreeconomical to implement.The federated modelIn the federated approach, a companycreates a network of separateentities with a common supportinginfrastructure. These might includeuniversities, hospitals, clinics,technology suppliers, data analysisfirms and lifestyle service providersbased in numerous countries. Theymight also include business units fromwithin the company itself, which itplaces at “arm’s length” (see Figure 4).The various participants have a mutualgoal – such as the management ofoutcomes in a given patient population.They also share funding, data, accessto patients and back-office services,and this interdependence is theglue that holds them together. Theyare rewarded for their efforts usingmeasures like increased life expectancyFigure 3: The different business modelsCollaborative: Federated ModelOwned: Fully Diversified Model Network of separate entities Network of entities owned by oneparent company Based on shared goals & infrastructure Draws on in-house and/or external assets Combines size with flexibility Based on provision of internally integratedproduct-service mix Spreads risk across business unitsVirtual VariantVenture Variant Network of contractors Portfolio of investments Activities coordinated by one companyacting as hub Based on sharing of intellectual property/capital growth Operates on project-by-project basis Stimulates entrepreneurialism & innovation Fee-for-service financial structure Spreads risk across portfolioSource: PricewaterhouseCoopers6PricewaterhouseCoopers

It may sometimes be hard to measurethe value different participants havecreated for two reasons. First, theparties in any collaboration typicallyvalue the contributions they havemade more highly than those of theirpartners. This is a problem that canbe solved with watertight contracts,robust performance indicators, goodgovernance and a proper audit trail.Second, assessing the impact ofdifferent forms of intervention can bevery difficult indeed.Medicines, diet and exercise all playa role in managing cardiovasculardisease, for example, but precisely howPharma 2020: Challenging business modelsPhyCcs ersurlsHospitaHow should the cake be sliced?DataAnalystsMa Gennu erfa ictyaperth essio ntreFederationnincsCliMore importantly still, the federatedmodel might encourage greatercross-fertilisation and deliver biggerimprovements in performance, withoutforfeiting any flexibility. The strongermembers of the network could helpthe weaker ones to improve – sincefederations have an incentive to performwell as a whole – but they could alsoreplace any participant that persistentlyunderperforms.ogyhnolTec pliersSu pt tighWe menageMan ntresCeThe federated model provides aframework for creating integratedpackages of products and services, andthus diversifying beyond a company’score offering. It also combines thebenefits of nimbleness and size. Itwould enable each player to build aspecific area of expertise, establish acompetitive advantage as a result ofthat expertise and sell its products,knowledge or skills, leaving activitiesthat are better performed by others toits partners within the federation.Figure 4: The federated modelComplianceCall Centreor quality-adjusted life years. And eachis rewarded in a manner that reflectsthe evidence base for the contribution ithas made (see sidebar, How should thecake be ieviUnSource: PricewaterhouseCoopersmuch? Various studies have establishedsome parameters. They show, forinstance, that high-frequency exercisecan improve the cardio-respiratoryfitness of patients with heart diseaseby at least 10% – and that, in turn,can reduce the mortality rate by 15%.We believe that many more studiesto evaluate the effectiveness of nonpharmacological interventions will beconducted in future, as healthcarepayers everywhere focus more heavilyon preventative measures.This approach is essentially a morecomplex variant of the co-developmentand co-distribution agreements we havetoday. In order for companies to workbetter collaboratively it is essential todefine upfront measurable componentsof delivery and value.Defining the value provided by eachplayer in the federation will then informhow each party should be rewarded this will be a combination of theoreticalanalysis and monitoring of outcomesand benefits to the patient. Clearlyto avoid the risk of litigation or theconstraints of exclusivity, the federationneeds to be underpinned by mutualtrust between all parties. However, thereare several examples of where this hasworked effectively such as a franchisingmodel where the value of a brand ismeasured and rewarded.7

Table of nSales&Most large pharmaceutical companiesalso use external contractors tosupplement their in-house resources,but very few firms have gone anyfurther (see sidebar, Shire’s virtualvision).18 There are very good reasonswhy pharmaceutical companies shouldoutsource their R&D, manufacturingand promotional activities where thirdparty alliances can provide a widerrange of opportunities, specialistskills and market access. A pharmacompany can then focus on the valueadding functions where they canleverage on their relationships, scaleand market knowledge – i.e., projectmanagement, business development,regulatory affairs, intellectual propertymanagement and the formation of goodrelationships with key opinion leaderstuacfnunIn the virtual variant of the federatedmodel most or all of a company’soperations are outsourced and thecompany itself acts as a managementhub, coordinating the activities ofits partners (see Figure 5). Severalindustries have already adoptedsome aspects of this model. Thesemiconductor industry typicallyoutsources its manufacturing inorder to concentrate on productdevelopment, for example, and anumber of companies in the medicaldevices sector are now following suit.17Similarly, strategic outsourcing ofdesign and manufacture to suppliershas redefined manufacturing functionswithin industries such as aerospace,computing and electronics.Figure 5: The virtual variant of the federated modelpmveloDeThe virtual variant of the federatedmodelResearchSource: PricewaterhouseCoopersShire’s virtual visionShire Pharmaceuticals is the epitome of a virtual company. It outsources almosteverything, from discovery to medical monitoring to data management tostatistics to medical writing. With the exception of its genetic therapy division,every product it develops has been purchased from an outside source, viain-licensing or acquisition.PricewaterhouseCoopers

GlaxoSmithKline has used a versionof the venture structure for manyyears. SR One, its evergreen fund,was established in 1985 and hasnow invested more than US 500m insome 30 private and public biotechcompanies focusing on drug discovery,development and delivery.20 OtherBig Pharma companies, such asNovartis and Pfizer, have also set upcorporate venture capital funds,21and AstraZeneca spun off part of itsgastrointestinal research operationinto a new company backed by aconsortium of private equity firms.22US investment bank Goldman SachsThe venture variant of the federatedmodel entails investing in a portfolio ofcompanies in return for a share of theintellectual assets and/or capital growththey generate, rather than outsourcingspecific tasks. Special purpose vehiclesare sometimes used to manage suchinvestments, because they offer severaladvantages in terms of risk sharing andintellectual property protection.A pharmaceutical company mightchoose to concentrate its investmentsin a particular therapeutic area orFigure 6: The venture variant of the federated modelOut-licensing/In-licensingThird par

process. It proposes that new technologies will enable the adoption of virtual R&D; and by operating in a more connected world the industry, in collaboration with researchers, governments, healthcare payers and providers, can address the changing needs of society