Transcription

volume 3issue 2spring 2014inside:shipwreck seekerwetlands warriorscuba schoolleadership legionsempoweredengineers3691215just add waterwright state makes a splash

Publisher and President ofWright State UniversityEditor andExecutive Director of MarketingGraphic Design and IllustrationContributing WritersEditorial AssistancePhotography EditorPhotographyDigital Imaging ManipulationDavid R. HopkinsDenise RobinowStephen RumbaughSeth Bauguess, Andrew Call,Jim Hannah, Bob Mihalek,and Kim PattonCory MacPherson, Ron WukesonWilliam JonesRoberta Bowers, William Jones,and Chris SnyderChris SnyderSubmit information, comments,and letters to:Wright State University Magazine4035 Colonel Glenn HighwaySuite 300Beavercreek, Ohio 45431Email: alumni news@wright.eduWright State University is growing to better serve our students. Construction is underway on two new campus locations: the Neuroscience Engineering Collaboration (NEC)Building (pictured) and the Student Success Center and Classroom Building.

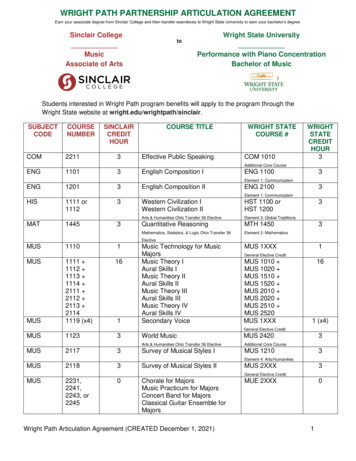

Wright State University Magazinewww.wright.edu/magazinespring 2014 VOLUME 3 ISSUE 2Wright State University Magazineis published twice a year by theOffice of Marketing. Distributionis to Wright State alumni, faculty,staff, and friends of the university.2From the President’s Desk3Great HuntGrad searches for famous shipwreck in the Great Lakes6Fen YenRetired professor champions local wetlands9SCUBA Program Known for its DepthWright State has trained more than 10,000 divers12Leading the PackRaiders lead state and national organizations15In DemandEmployers eagerly await Lake Campus engineers16Wright HydroplanesArchive photos show early Wright brothers’ watercraft18Building BridgesTony Ortiz continues advocacy for Latino community19Rock SteadyGeology student getting national attention20A Daughter’s LoveGrad established scholarship for Hispanic nursing students22University News24Alumni News28AlumNotes31Athletics News

FROM THE PRESIDENT’S DESKWelcome to this issue of Wright State University Magazine.After one of the worst winters in history, I am so lookingforward to the arrival of spring. It’s one of my favorite seasons.I appreciate not only its beauty but what it represents—a new beginning. As we await the rebirth that comes withspring, it seems appropriate that we focus our spring issueon another element of nature that represents the continuouscycle of life: water.Leonardo da Vinci once said, “When you put your hand ina flowing stream, you touch the last that has gone before andthe first of what is still to come.” In many ways, water reflectsour own journeys through life. Just as one body of water flowsinto another, the currents and tides of time move us along themany streams of our lives.In this issue, we examine how water—one of our planet’smost precious resources—ebbs and flows through the WrightState community. Come with us as the tide recedes back intime to the beginning of Wright State’s scuba program. Diveinto the depths of Lake Michigan, where one of our graduatessearches for a long-lost ship. And sink into some localwetlands that have been preserved with the help of a retiredbiology professor.To quote renowned oceanographer Jacques Cousteau, “Weforget that the water cycle and the life cycle are one.” I hopethis issue reminds you how important water is to each of us—for our history, our recreation, and our survival.Until our next issue.Warmest regards from campus,David R. HopkinsPresidentWright State University2

FEATUREgreat huntwright state alumnus steve libertmay be closing in on locatingthe long-lost ship the griffinBy Bob MihalekThis page: A diver with Great Lakes Exploration Groupsurveys a beam at the bottom of Lake Michigan thatSteve Libert believes is from the Griffin.Pages 4 and 5: Kathie (’78) and Steve Libert (’81), inset;the Great Lakes Exploration Group heading out onLake Michigan during a diving expedition in June 2013.photos courtesy Great Lakes Exploration Group LLC.3

FEATURESteve Libert has spentthe last 30 years searchingfor his Holy Grail: theGriffin, the flagship ofFrench explorer La Sallethat sank in the Great Lakesin the 17th century.After decades ofresearch, thousands ofdives, and years of legalwrangling, the Wright StateUniversity alumnus thinks he is close to finding the ship.Last summer, Libert–who along with his wife, Kathie,operates the Great Lakes Exploration Group–led an expeditionof divers and archeologists in northern Lake Michigan, wherehe believes the Griffin sank.While evidence found during the expedition has so far beeninconclusive, Libert is convinced he’s found part of the Griffin.Libert effuses passion when talking about La Salle, theGriffin, and history. His search is driven by the ship’s place inhistory and the mystery surrounding its disappearance. It’s whyhe calls the Griffin the “Holy Grail of the Great Lakes.”“If you think of the importance of this ship and what itwould take to find it—it was the first deck vessel to sink in theGreat Lakes,” he said.Libert’s interest in underwater exploration and shipwrecksisn’t limited to the Griffin. He has consulted on the Titanic, thesearch for General Tomoyuki Yamashita’s hidden treasure fromWorld War II, and the recovery of the Confederate submarineCSS Hunley.The Griffin, or Le Griffon as it is called in French, wasconstructed by René-Robert Cavelier Sieur de La Salle on theNiagara River near Niagara Falls. La Salle and a crew of 32set out on the Griffin in 1679, sailing through Lakes Erie andHuron, stopping at Washington Island near the entrance to4Green Bay on western Lake Michigan.La Salle and most of the crew disembarked and continuedsouth by canoe. He sent the Griffin, with a crew of six and a loadof furs, back east for more supplies in September 1679. Theship was never seen again.Searching for a passage to China and Japan, La Salleeventually sailed the Mississippi, claiming for France much ofthe Great Lakes region and the Mississippi River basin. A portionof these lands would become part of the Louisiana Purchase.Noeleen McIlvenna, associate professor of history at WrightState University, said La Salle occupies an important part ofthe history of both the U.S. and Canada, playing a huge role increating the lucrative French-Algonquian fur trade from 1666to 1687.“His alliances with many groups of American Indianswere founded on treating them respectfully as equal businesspartners,” she said. “Because of his willingness to learn otherlanguages and cultures, Indians helped him map routes andestablish trading posts throughout the Great Lakes, around theMidwest, and down the Mississippi to Louisiana. He stands outfrom the English settlers as a reminder of the potential for aracially tolerant America.”Libert fondly recalls the day he first learned of La Salle andthe Griffin.He was in eighth-grade history class in Huber Heights,Ohio, near Wright State. His teacher, Mr. Kelly, was lecturingabout early European explorations of the New World. Libert wassmitten by the tale of the Griffin and La Salle’s adventures in theGreat Lakes and down the Mississippi.As he walked around the classroom, Libert recalled, his teacherput his right hand on Libert’s left shoulder and said, “Who knows?Maybe somebody in this class will find it someday.”This sparked something in the young Libert. Caught up inthe “thrill of adventure,” he grew enthralled with the Griffin.“What kid doesn’t think about a ship and treasure?” he asked.

He initially went to Ohio State to playfootball, and after injuries cut his playingdays short, he left Columbus and enrolled inWright State. He worked during the day andtook classes at night. Libert never lost hisadventurous spirit. He learned to fly and todive underwater.After graduating from Wright State in1981 with a B.A. in political science, Libertworked for the Defense Mapping Agency,which today is the National GeospatialIntelligence Agency. He remained at theagency for 25 years as an intelligence analystuntil he retired in 2013 so he could focuson the Griffin project. He and Kathie, whograduated from Wright State in 1978 witha B.F.A. in art, moved to northern Michigan.He started narrowing in on what hethought was the location of the Griffin as hesearched northern Michigan with friends.After five years, Libert discovered abeam sticking straight out of the bottomof the lake while diving in 2001. “When Ifound it I knew it was a bowsprit,” he said.“There’s no question about it.”Furthermore, Libert thought the beamcould be the Griffin’s bowsprit, a poleextending from a vessel’s prow.Years of legal battle ensued betweenLibert and the state of Michigan aboutownership of the find. Eventually, Franceintervened, claiming that the Griffinbelongs to France because King Louis XIVfinanced La Salle’s explorations.The parties reached a breakthroughagreement several years ago. Itacknowledged France’s ownership ofthe vessel and gave Libert’s Great LakesExploration Group permission to continueinspecting the site.In June 2013, the exploration group andthree French archaeologists spent a weekon Lake Michigan examining the beam andsearching for the vessel.Libert had hoped that the ship’sremains would be buried in the mudbeneath the bowsprit, but divers whoexcavated the lake bottom found nothingbut sediment and zebra mussels below it.Libert’s team plans to resume searchingnorthern Lake Michigan in the spring of2014 to locate the Griffin.Since it was located, the beam hasundergone a number of tests. Carbontesting on wood samples have notpinpointed the exact age of the beam,instead concluding it could be anywherefrom 50 to 350 years old. A CT scan wasconducted on the timber at a Michiganhospital to try to determine its age byobtaining a tree ring image. Unfortunately,the scan was inconclusive.The French experts who participated inthe expedition conducted an archaeologicalanalysis of the piece. While they couldnot determine if the beam was part of theGriffin, they said the timber was consistentwith a bowsprit from the 17th century.Their report also found that a portion ofthe artifact had likely been buried “in thesediment of the lake a long time, for atleast one hundred years and perhaps evenseveral hundred years.”Some researchers, including expertswith the state of Michigan, dispute thatthe finding could be from the Griffin,contending that it is instead part of a poundnet stake, an underwater fishing apparatusused in the Great Lakes in the 19th andearly 20th centuries.Libert remains convinced the pieceis the bowsprit of the Griffin and isencouraged by the French report.“When you start adding up all the piecesit’s obvious,” he said. “It can only belong toone vessel and that’s the Griffin. No othervessel sailed that area at that time and theydidn’t have that kind of construction, atleast not documented.”Visit greatlakesexploration.org to readmore about the search for the Griffin.5

FEATUREfen yenvital wetland owes existence tobiology professor jim amonBy Jim HannahThe boardwalk sponges down into marshy ground under the weight of the naturewalkers. Cattails sway, woodpeckers peck, and colorful insects and plants paintthe landscape.Jim Amon is leading the way. The retired Wright State University biologyprofessor has spent the past 25 years of his life helping preserve and restore theBeaver Creek Wetlands—2,000 acres of nature salad that is home to everything fromthe yellow warbler to the spotted turtle to the blue-leaved willow.“By Yellowstone standards, it’s nothing; but in an urban area like this, it’s huge,”said Amon.How huge?Wetlands are rare, existing only in the right geologic settings. And nearly 90percent of the wetlands that once freckled Ohio are gone, most of them drained sothe land could be farmed.“It’s something you just can’t find in a lot of other places in the world,” Amonsaid. “And I don’t think anybody else in the world has a resource like we do thisclose to a major educational institution.”The 10-mile-long wetland is a five-minute drive from Wright State. Studentsuse it for research projects and have served as volunteers to help in its restoration.One intern cleaned and planted seeds for 6,000 new wetland plants. Severalstudents have set up stations to monitor water levels and water quality.In September, the 70-year-old Amon was honored with a Lifetime AchievementAward by Partners for the Environment, whose mission is to protect, restore,preserve, and promote the resources of the Great Miami River and Miami RiverWatersheds in an 18-county region.Amon led efforts to purchase wetland acreage and restore it; lobbied for state,federal, and local resources; and helped install boardwalks to make the wetlandsaccessible to the public. He also grew plants for replanting in the wetland and6Nearly 90% ofthe wetlands thatonce freckled Ohioare gone, most ofthem drained sothe land couldbe farmed.

recruited students and other volunteersto control invasive plants, inventory birdpopulations, and install interpretivesignage. Amon estimates he has attendedhundreds of late-night zoning meetingsover the past 25 years.“Dr. Amon has devoted his time,expertise, energy, and continuouscommitment to the wetlands,” said DavidNolin, director of conservation for FiveRivers MetroParks.Amon’s passion for nature sprangfrom growing up on a farm in southwestOhio near Batavia, where he would hikeall over the county and explore the woods.“We had two creeks running throughthe property,” he recalled. “I wouldoccasionally dam them up and make littlewetlands and flood the road. My momwould say, ‘Get down here and clear outthat dam.’”Amon obtained his bachelor’sdegree in biology from the University ofCincinnati and his master’s and Ph.D. inmarine biology from William & Mary.He served in the U.S. Army during the Vietnam War, stationed at the Dugway ProvingGrounds in Utah from 1968 to 1970.“I worked on biological warfare agents,” he said. “That gave me some experience inthings like food-borne diseases.”Amon arrived at Wright State in 1974 to teach marine biology. He later developed themicrobiology and food microbiology courses. He is currently a retired professor, but stillteaches a wetlands biology course and does some guest lectures.Amon discovered the wetland shortly after he and his wife moved into the area fromVirginia. Amon was thrilled. He had just finished working in the Chesapeake Bay wetlands,one of the largest in the world.He became involved with preserving and restoring the Beaver Creek Wetlands in 1988as part of a group of concerned citizens.“These were people who weren’t just out on a lark; they were pretty serious about this,”Amon said. “They understood how important this wetland was and wanted to do whateverthey could do to preserve it.”With his scientific technical background, Amon helped lend credibility to what wouldbecome the Beaver Creek Wetlands Association, a group that counted among its membersofficials from the Ohio Department of Natural Resources, the Ohio EnvironmentalProtection Agency, and the Nature Conservancy.“One of the most gratifying things about working with the Beaver Creek Wetlands isworking with people of a like mind who are as dedicated as they are,” Amon said.Called the kidneys of the earth, wetlands filter and clean groundwater. For example, wetlandscan turn what could be dangerous levels of nitrates from farm-runoff fertilizer into nitrogen thatphoto: gravitas docufilms7

FEATUREis harmlessly released into the air. As part of a researchproject, Amon created a wetland at nearby WrightPatterson Air Force Base that eliminated solvents thathad contaminated groundwater.Wetlands also modify the surrounding airtemperature, keeping it cooler in the summer andwarmer in the winter. They also serve as naturepreserves for wildlife and endangered plants.“We have close to 500 species of plants outthere; that’s like a tropical rain forest,” Amon said.“It’s so difficult to find anyplace that has that muchdiversity. Most of the things that are endangeredthat still exist are in wetlands because those are thelast refuges.”The largest wetlands in the world are theAmazon River basin and the west Siberian plain.The Beaver Creek Wetlands is actually a fen,which is a wetland fed by groundwater. Thegroundwater at Beaver Creek flows throughlimestone, delivering minerals that keep the pHof the fen stable and enable it to help protect thepurity of the underground aquifer.To restore the wetland, Amon and volunteersinstalled some low dams, blocked drainage ditches,and blocked or removed terra cotta field drainagetiles, enabling the groundwater to rise to the surface.The association also negotiated buffer zonesbetween the wetlands and nearby housingdevelopments. There is even a ban on lights thatshine into the wetland.In addition, it was decided to installboardwalks because it was difficult to wade intothe wetland, and the waders were making pathsthat were taken over by invasive plants. So theassociation launched a fundraising campaign andbought materials for two boardwalks, the largest ofwhich is about a mile long and loops back on itselfthrough the tangle of plant life.“We don’t want to love the wetland to death, butwe need to get the public out to see it,” Amon said.“They have to be able to see what they preserved,and it’s worth seeing.”An estimated 15,000 people use the boardwalkat the wheelchair-accessible Siebenthaler Fen, onFairgrounds Roads in Beavercreek, each year.Each May, the wetland hosts the AudubonBirdathon, a fundraising event in whichparticipants attempt to identify as many species aspossible. And in July, there is a butterfly watch. Afew years ago, two Monarch butterflies tagged bythe international monarch conservation projectMonarch Watch were spotted in the wetland andtheir migration later tracked to Mexico.“There is a lot of cool stuff going on,” Amon said.Visit beavercreekwetlands.org to learn moreabout the Beaver Creek Wetlands Association.8

FEATUREwright state programscuba program acelebratesits 40th birthdayknown for its depthBy Seth BauguessA Wright State University programthat routinely dumps students infreezing waters, has incorporated theuse of former Navy SEALs, and is knownin such faraway places as the Polynesianisland nation of Tonga, is about tocelebrate its 40th birthday.The scuba program at Wright Statehas educated over 10,000 students since1974. As far as Serbia and Japan, theprogram with no local oceanic coastlineis known as one of the best places inthe world to receive diving instruction.The chief dive-training educator forthe Dayton region, it’s responsible foreducating many of the forensic divers inthe area and sends engineering, biology,and geology students out into the jobmarket with game-changing skills.Started by a man recently inductedinto the Diving Industry Hall of Fame,it has pioneered safety protocols andprocedures, and famously sent collegestudents to the depths of freezing, zerovisibility rivers, lakes, and gravel pits allover North America.Two prominent dive instructors andfaculty members can lay claim to theprogram’s undeniable success and safetyrecord—no Wright State student has everbeen injured during scuba instruction.The first is program creator Dan Orr.The second is current scuba programcoordinator Regina Bier.Orr’s in the waterDan Orr grew up in South Florida andoften dove for shells and treasures withhis brother at his grandparent’s home inthe Florida Keys. An expert recreationaldiver at a young age, he moved to theMiami Valley in the ’60s and came toWright State at the end of the decade tostudy biology.Orr finished a bachelor’s degree in’73 and began graduate school the nextyear. By then, he’d been teaching divingin southwest Ohio for a while as a scubainstructor in West Carrollton, at a scubaclub at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base,and for the Dayton YMCA. When heheard Wright State was going to builda pool, he was convinced a new scubaprogram should follow.Though he was not the first choice tolead the program, it didn’t take long forOrr—whose persistence to help in anyway made him impossible to ignore—tobe tasked with shaping the program. Orrwas given carte blanche to develop theprogram the best way he saw fit.“I’d been teaching a while at thatpoint and I just felt that teaching theminimum standards was not enough,”said Orr on the phone from his homein Idaho. “I wanted people to be ableto use the skills for a career or expertrecreational use.”Orr began crafting a program fordivers based in the Midwest who wouldlikely do most of their diving in theregion, too. The entry-level class utilizedthe Wright State pool for their confinedwater training before going to the openwater to complete requirements forcertification. Subsequent classes rarelyoccurred anywhere but in the field.Students dove in ponds, lakes, and riversall over the area. Open water dives in thewinter months were common.“If we were going to teach a studenta skill, we wanted to teach them to dothat skill in any condition, withoutexception,” said Orr. Word was gettingout that a fantastic program was beingbuilt. Soon Orr’s staff included formerNavy divers and even former SEALs.Students who worked their way up9

FEATURELeft: Dan Orr, creator of the Wright State scuba program andmember of the Diving Industry Hall of Fame, is as well knownin the diving community as Jacques Cousteau.Below top: Wright State diving students pose for a photo atone of the many field diving sites in the Dayton area theyfrequented during their instruction.Below bottom: Chris Buck, left, and Ken Charpie, forensicdivers with Wright State University, were part of the searchFriday, Sept. 27, 2013, for the remains of Erica Baker.photo: Dayton Daily News / Jim Noelkerto the advanced research and diving course—a course designed forstudents to apply to their careers—would tackle five diving-relatedprojects each summer. Projects centering on environmental andaquatic ecology, deep diving, and decompression diving led studentsacross the country. During an archeological dive project, studentsdove on a shipwreck in Canada and were tasked with salvaging bothsmall objects, as well as objects weighing up to a ton. The marinebiology project took students to the Gulf of Mexico.After working with the university for 20 years, Orr beganworking with the fledgling Divers Alert Network (DAN). As theDAN regional coordinator and instructor, Orr designed industrystandard safety classes, protocols, and programs. Orr began atDAN as a volunteer and retired decades later as the president. Lastyear he was inducted into the Diving Industry Hall of Fame, wherehe joined world-famous underwater explorer Jacques Cousteau,among many others.A legacy upheldWhile teaching scuba at Wright State, Orr came across adedicated and eager young diving student named Regina Bier.Bier’s father was an avid diver in the Dayton area in the ’50s,when the sport was at its recreational infancy. Her father didsome diving for local law enforcement and even the FBI. His bestfriend and dive partner was Ray Tussey, who later became one ofthe founding instructors with NAUI, the National Association ofUnderwater Instructors. One of Tussey’s early students was Orr.10“I can remember hearing my father’s stories and seeing hisdiving gear hanging on our garage wall and thinking ‘I just want todive,’” said Bier, adjunct faculty and detective with the KetteringPolice Department. “I was just hell-bent on learning how. I came toWright State, saw it had a program, and thought, ‘this is my chance.’”Bier first trained to become an excellent swimmer, and thenenthusiastically studied under Orr to become an expert diver.Orr’s commitment to safety and commanding presence onlysolidified Bier’s interest in finding a way to incorporate diving intoher career. After graduation, she began working in law enforcement.A few years later, after Orr had moved on, Bier picked up thepieces of a program that had slipped in quality but was not deadin the water. She vowed to meet the standards her mentor hadestablished before her.“He left some really big shoes to fill,” said Bier, who wasinducted into the Women Diver Hall of Fame in 2011 and is aNAUI-certified course director—the highest level of certificationthe association gives to recreational diving teachers.The first thing she did was re-establish a rock-solid basic scubadiving class again. Her goal was to return the program to a state inwhich students could go from beginner, to master diver, to instructor.Soon the numbers were back up, and about 75 percent of studentsfrom the beginner class were moving on to advanced classes.The 25 percent that just want to learn the sport take withthem a skill and experiences that change their lives. “For thoseof us not looking to make a career in diving, there’s still a lot to

experience as a recreational diver—it’sa fun, relaxing sport that’s added a newdimension to my life,” said TiffanyFridley, who’s taken the basic open waterclass and the advanced diver class and isin the master diver class this spring.Those same advanced classes have alsobeen training the forensic divers the MiamiValley has largely relied on for the last twodecades. The need for search and recoveryevidentiary dives is not great enough in thearea that any one police or fire departmentcan afford to keep a team on board. Bierhas often been the only game in town. Onnearly all of the dives she’s done, she’sloaded her team with Raiders.“When I need divers to assist mewith evidence diving, since I knowthey’ve been trained and I know theircertifications are current and they’rein the water regularly right now, it onlymakes sense,” said Bier.In fact during a recent dive of aMontgomery County gravel pit for theinfamous Erica Baker cold case, everydiver was a current or former scubastudent at Wright State. Baker was anine-year-old-girl who disappearedfrom her Kettering neighborhoodin 1999 and has never been found.Evidence has long pointed to her bodybeing disposed of in a local body of water.“In a dive like that, there’s zerovisibility. Everything in that type ofsearch is done with touch and feel andit takes hours underwater,” said Bier.“Everything they can do where they cansee, I want my students to be able to dojust as well when they can’t see.”Today she teaches all levels of scubaat Wright State and draws studentsinterested in careers in engineering,biology, marine biology, geology,oceanography, and public safety. Onestudent was in the first internship classat the Newport Aquarium in northernKentucky and is now a dive safety officerthere. Another just left the programto go to commercial diving school toprepare for a high-tech career of deepoceanic dives supporting oilrigs andother nautical applications. Chris Buck,a certified divemaster who worked withBier on the recent Baker search, hopes toincorporate his diving skills into a careerin emergency planning.“These forensic dives often meansearching with our hands the entire time,”said Buck. “Imagine that you have thickgloves on, are blindfolded, and are tryingto distinguish between a stick and bone.”Bier uses stress training, zerovisibility training, entanglementtraining, and search training techniquesto prepare students for whatever theirdive futures may offer.“They’re learning to handle not onlytheir best day of diving, but I teach themhow to handle their worst day,” said Bier.“That legacy began with Dan Orr, and Istrive to maintain that every day.”Right, top: Wright State scuba programcoordinator Regina Bier is also a detectivewith the Kettering Police Department.Right, bottom: Wright State diving internspose for a photo in the tank with a sea turtleat the Newport Aquarium in Kentucky.11

LEADERSLeft to right: Simone Polk, Spencer Brannon, David R. Hopkins, Dan Krane, and Tony Ortiz12

leading the packwright state faculty, staff, and studentshold top national, state leadership positionsBy Jim HannahLeaders are special people. They areusually intelligent and charismatic withvision and values. People naturally justwant to follow them.Wright State University is teeming withsuch leaders. They hold high national andstate positions and populate influentialorganizations in education, science, labor,health, athletics, and the arts.David R. Hopkins, president of WrightState University, is chair of the InterUniversity Council of Ohio, member ofthe Higher Education Capital FundingCommission of Ohio, and serves on theNational Collegiate Athletic Association(NCAA), Division I, Executive Committeeand Board of Directors. He is also chair ofthe Wright Brothers Institute, vice chairof the Advanced Technical IntelligenceCenter, and co-chair of the Ohio Boardof Regents Articulation and TransferAdvisory Council.Dan Krane, professor of biology,is chair of the Ohio Faculty Council.He represents the faculty at Ohio’s 13public, four-year universities whenhe speaks to the chancellor, the Boardof Regents, and state legislatures. Thecouncil passes resolutions on mattersbefore the Ohio House and Senate andcoordinates activities between universitieson curricular issues such as the transitionfrom quarters to semesters.Tony Ortiz, associate vice president forLatino affairs, is commissioner on the OhioCommission of Hispanic/Latino Affairs.The commission advises the governor,General Assembly, and state agencieson matters affecting Hispanic Ohioansby issuing reports, proposing programs,commenting on legislation, and conductingpolicy-related research. Its mission is toconnect the diverse Latino communitiesacross the state and to build the capacityof Latino community organizations. Ortizis also the state vice president for theElderly-League of United Latin AmericanCitizens, which works to advancethe economic condition, educationalattainment, political influence, housing,health, and civil rights of the Hispanicpopulation of the United States.Rudy Fichtenbaum, professor ofeconomics, is president of the AmericanAssociation of University Professors.The mission of the AAUP, whichrepresents about 47,000 professors andother academics, is to advance academicfreedom and sh

World War II, and the recovery of the Confederate submarine CSS Hunley. The Griffin, or Le Griffon as it is called in French, was constructed by René-Robert Cavelier Sieur de La Salle on the Niagara River near Niagara Falls. La Salle and a crew of 32 set out on the Griffin in 1679, sailing through Lakes Erie and