Transcription

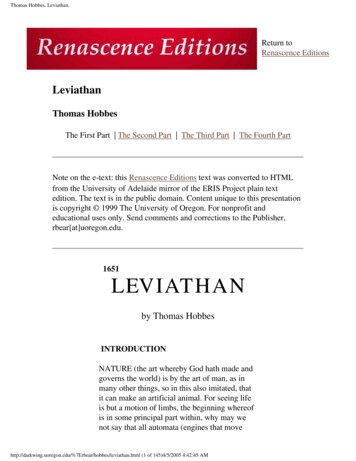

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.Return toRenascence EditionsLeviathanThomas HobbesThe First Part The Second Part The Third Part The Fourth PartNote on the e-text: this Renascence Editions text was converted to HTMLfrom the University of Adelaide mirror of the ERIS Project plain textedition. The text is in the public domain. Content unique to this presentationis copyright 1999 The University of Oregon. For nonprofit andeducational uses only. Send comments and corrections to the Publisher,rbear[at]uoregon.edu.1651L EV I AT H A Nby Thomas HobbesINTRODUCTIONNATURE (the art whereby God hath made andgoverns the world) is by the art of man, as inmany other things, so in this also imitated, thatit can make an artificial animal. For seeing lifeis but a motion of limbs, the beginning whereofis in some principal part within, why may wenot say that all automata (engines that viathan.html (1 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.themselves by springs and wheels as doth awatch) have an artificial life? For what is theheart, but a spring; and the nerves, but so manystrings; and the joints, but so many wheels,giving motion to the whole body, such as wasintended by the Artificer? Art goes yet further,imitating that rational and most excellent workof Nature, man. For by art is created that greatLEVIATHAN called a COMMONWEALTH,or STATE (in Latin, CIVITAS), which is butan artificial man, though of greater stature andstrength than the natural, for whose protectionand defence it was intended; and in which thesovereignty is an artificial soul, as giving lifeand motion to the whole body; the magistratesand other officers of judicature and execution,artificial joints; reward and punishment (bywhich fastened to the seat of the sovereignty,every joint and member is moved to performhis duty) are the nerves, that do the same in thebody natural; the wealth and riches of all theparticular members are the strength; saluspopuli (the people's safety) its business;counsellors, by whom all things needful for itto know are suggested unto it, are the memory;equity and laws, an artificial reason and will;concord, health; sedition, sickness; and civilwar, death. Lastly, the pacts and covenants, bywhich the parts of this body politic were at firstmade, set together, and united, resemble thatfiat, or the Let us make man, pronounced byGod in the Creation.To describe the nature of this artificial man, Iwill consider First, the matter thereof, and theartificer; both which is man.Secondly, how, and by what covenantsit is made; what are the rights and justpower or authority of a sovereign; andwhat it is that preserveth and hobbes/leviathan.html (2 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan. Thirdly, what is a ChristianCommonwealth.Lastly, what is the Kingdom ofDarkness.Concerning the first, there is a saying muchusurped of late, that wisdom is acquired, not byreading of books, but of men.Consequently whereunto, those persons, thatfor the most part can give no other proof ofbeing wise, take great delight to show whatthey think they have read in men, byuncharitable censures of one another behindtheir backs. But there is another saying not oflate understood, by which they might learntruly to read one another, if they would take thepains; and that is, Nosce teipsum, Read thyself:which was not meant, as it is now used, tocountenance either the barbarous state of menin power towards their inferiors, or toencourage men of low degree to a saucybehaviour towards their betters; but to teach usthat for the similitude of the thoughts andpassions of one man, to the thoughts andpassions of another, whosoever looketh intohimself and considereth what he doth when hedoes think, opine, reason, hope, fear, etc., andupon what grounds; he shall thereby read andknow what are the thoughts and passions of allother men upon the like occasions. I say thesimilitude of passions, which are the same inall men,- desire, fear, hope, etc.; not thesimilitude of the objects of the passions, whichare the things desired, feared, hoped, etc.: forthese the constitution individual, and particulareducation, do so vary, and they are so easy tobe kept from our knowledge, that the charactersof man's heart, blotted and confounded as theyare with dissembling, lying, counterfeiting, anderroneous doctrines, are legible only to him thatsearcheth hearts. And though by men's actionswe do discover their design sometimes; yet athan.html (3 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.do it without comparing them with our own,and distinguishing all circumstances by whichthe case may come to be altered, is to decipherwithout a key, and be for the most partdeceived, by too much trust or by too muchdiffidence, as he that reads is himself a good orevil man.But let one man read another by his actionsnever so perfectly, it serves him only with hisacquaintance, which are but few. He that is togovern a whole nation must read in himself, notthis, or that particular man; but mankind: whichthough it be hard to do, harder than to learn anylanguage or science; yet, when I shall have setdown my own reading orderly andperspicuously, the pains left another will beonly to consider if he also find not the same inhimself. For this kind of doctrine admitteth noother demonstration.THE FIRST PARTOF MANCHAPTER IOF SENSECONCERNING the thoughts of man, I willconsider them first singly, and afterwards intrain or dependence upon one another. Singly,they are every one a representation orappearance of some quality, or other accidentof a body without us, which is commonlycalled an object. Which object worketh on theeyes, ears, and other parts of man's body, andby diversity of working produceth diversity ofappearances. The original of them all is thatwhich we call sense, (for there is no bes/leviathan.html (4 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.in a man's mind which hath not at first, totallyor by parts, been begotten upon the organs ofsense). The rest are derived from that original.To know the natural cause of sense is not verynecessary to the business now in hand; and Ihave elsewhere written of the same at large.Nevertheless, to fill each part of my presentmethod, I will briefly deliver the same in thisplace.The cause of sense is the external body, orobject, which presseth the organ proper to eachsense, either immediately, as in the taste andtouch; or mediately, as in seeing, hearing, andsmelling: which pressure, by the mediation ofnerves and other strings and membranes of thebody, continued inwards to the brain and heart,causeth there a resistance, or counter-pressure,or endeavour of the heart to deliver itself:which endeavour, because outward, seemeth tobe some matter without. And this seeming, orfancy, is that which men call sense; andconsisteth, as to the eye, in a light, or colourfigured; to the ear, in a sound; to the nostril, inan odour; to the tongue and palate, in a savour;and to the rest of the body, in heat, cold,hardness, softness, and such other qualities aswe discern by feeling. All which qualitiescalled sensible are in the object that causeththem but so many several motions of thematter, by which it presseth our organsdiversely. Neither in us that are pressed arethey anything else but diverse motions (formotion produceth nothing but motion). Buttheir appearance to us is fancy, the samewaking that dreaming. And as pressing,rubbing, or striking the eye makes us fancy alight, and pressing the ear produceth a din; sodo the bodies also we see, or hear, produce thesame by their strong, though unobservedaction. For if those colours and sounds were inthe bodies or objects that cause them, viathan.html (5 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.could not be severed from them, as by glassesand in echoes by reflection we see they are:where we know the thing we see is in oneplace; the appearance, in another. And thoughat some certain distance the real and veryobject seem invested with the fancy it begets inus; yet still the object is one thing, the image orfancy is another. So that sense in all cases isnothing else but original fancy caused (as Ihave said) by the pressure that is, by the motionof external things upon our eyes, ears, andother organs, thereunto ordained. But thephilosophy schools, through all the universitiesof Christendom, grounded upon certain texts ofAristotle, teach another doctrine; and say, forthe cause of vision, that the thing seen sendethforth on every side a visible species, (inEnglish) a visible show, apparition, or aspect,or a being seen; the receiving whereof into theeye is seeing. And for the cause of hearing, thatthe thing heard sendeth forth an audiblespecies, that is, an audible aspect, or audiblebeing seen; which, entering at the ear, makethhearing. Nay, for the cause of understandingalso, they say the thing understood sendethforth an intelligible species, that is, anintelligible being seen; which, coming into theunderstanding, makes us understand. I say notthis, as disapproving the use of universities: butbecause I am to speak hereafter of their officein a Commonwealth, I must let you see on alloccasions by the way what things would beamended in them; amongst which thefrequency of insignificant speech is one.CHAPTER IIOF IMAGINATIONTHAT when a thing lies still, unless somewhatelse stir it, it will lie still for ever, is a truth thatno man doubts of. But that when a thing is inmotion, it will eternally be in motion, leviathan.html (6 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.somewhat else stay it, though the reason be thesame (namely, that nothing can change itself),is not so easily assented to. For men measure,not only other men, but all other things, bythemselves: and because they find themselvessubject after motion to pain and lassitude, thinkeverything else grows weary of motion, andseeks repose of its own accord; littleconsidering whether it be not some othermotion wherein that desire of rest they find inthemselves consisteth. From hence it is that theschools say, heavy bodies fall downwards outof an appetite to rest, and to conserve theirnature in that place which is most proper forthem; ascribing appetite, and knowledge ofwhat is good for their conservation (which ismore than man has), to things inanimate,absurdly.When a body is once in motion, it moveth(unless something else hinder it) eternally; andwhatsoever hindreth it, cannot in an instant, butin time, and by degrees, quite extinguish it: andas we see in the water, though the wind cease,the waves give not over rolling for a long timeafter; so also it happeneth in that motion whichis made in the internal parts of a man, then,when he sees, dreams, etc. For after the objectis removed, or the eye shut, we still retain animage of the thing seen, though more obscurethan when we see it. And this is it the Latinscall imagination, from the image made inseeing, and apply the same, though improperly,to all the other senses. But the Greeks call itfancy, which signifies appearance, and is asproper to one sense as to another. Imagination,therefore, is nothing but decaying sense; and isfound in men and many other living creatures,as well sleeping as waking. The decay of sensein men waking is not the decay of the motionmade in sense, but an obscuring of it, in suchmanner as the light of the sun obscureth thelight of the stars; which stars do no viathan.html (7 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.exercise their virtue by which they are visiblein the day than in the night. But becauseamongst many strokes which our eyes, ears,and other organs receive from external bodies,the predominant only is sensible; therefore thelight of the sun being predominant, we are notaffected with the action of the stars. And anyobject being removed from our eyes, thoughthe impression it made in us remain, yet otherobjects more present succeeding, and workingon us, the imagination of the past is obscuredand made weak, as the voice of a man is in thenoise of the day. From whence it followeth thatthe longer the time is, after the sight or sense ofany object, the weaker is the imagination. Forthe continual change of man's body destroys intime the parts which in sense were moved: sothat distance of time, and of place, hath one andthe same effect in us. For as at a great distanceof place that which we look at appears dim, andwithout distinction of the smaller parts, and asvoices grow weak and inarticulate: so also aftergreat distance of time our imagination of thepast is weak; and we lose, for example, of citieswe have seen, many particular streets; and ofactions, many particular circumstances. Thisdecaying sense, when we would express thething itself (I mean fancy itself), we callimagination, as I said before. But when wewould express the decay, and signify that thesense is fading, old, and past, it is calledmemory. So that imagination and memory arebut one thing, which for diverse considerationshath diverse names.Much memory, or memory of many things, iscalled experience. Again, imagination beingonly of those things which have been formerlyperceived by sense, either all at once, or byparts at several times; the former (which is theimagining the whole object, as it was presentedto the sense) is simple imagination, as viathan.html (8 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.one imagineth a man, or horse, which he hathseen before. The other is compounded, whenfrom the sight of a man at one time, and of ahorse at another, we conceive in our mind acentaur. So when a man compoundeth theimage of his own person with the image of theactions of another man, as when a manimagines himself a Hercules or an Alexander(which happeneth often to them that are muchtaken with reading of romances), it is acompound imagination, and properly but afiction of the mind. There be also otherimaginations that rise in men, though waking,from the great impression made in sense: asfrom gazing upon the sun, the impressionleaves an image of the sun before our eyes along time after; and from being long andvehemently attent upon geometrical figures, aman shall in the dark, though awake, have theimages of lines and angles before his eyes;which kind of fancy hath no particular name, asbeing a thing that doth not commonly fall intomen's discourse.The imaginations of them that sleep are thosewe call dreams. And these also (as all otherimaginations) have been before, either totallyor by parcels, in the sense. And because insense, the brain and nerves, which are thenecessary organs of sense, are so benumbed insleep as not easily to be moved by the action ofexternal objects, there can happen in sleep noimagination, and therefore no dream, but whatproceeds from the agitation of the inward partsof man's body; which inward parts, for theconnexion they have with the brain and otherorgans, when they be distempered do keep thesame in motion; whereby the imaginationsthere formerly made, appear as if a man werewaking; saving that the organs of sense beingnow benumbed, so as there is no new objectwhich can master and obscure them with amore vigorous impression, a dream must eviathan.html (9 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.be more clear, in this silence of sense, than areour waking thoughts. And hence it cometh topass that it is a hard matter, and by manythought impossible, to distinguish exactlybetween sense and dreaming. For my part,when I consider that in dreams I do not oftennor constantly think of the same persons,places, objects, and actions that I do waking,nor remember so long a train of coherentthoughts dreaming as at other times; andbecause waking I often observe the absurdity ofdreams, but never dream of the absurdities ofmy waking thoughts, I am well satisfied that,being awake, I know I dream not; though whenI dream, I think myself awake.And seeing dreams are caused by thedistemper of some of the inward parts of thebody, diverse distempers must needs causedifferent dreams. And hence it is that lying coldbreedeth dreams of fear, and raiseth the thoughtand image of some fearful object, the motionfrom the brain to the inner parts, and from theinner parts to the brain being reciprocal; andthat as anger causeth heat in some parts of thebody when we are awake, so when we sleep theoverheating of the same parts causeth anger,and raiseth up in the brain the imagination ofan enemy. In the same manner, as naturalkindness when we are awake causeth desire,and desire makes heat in certain other parts ofthe body; so also too much heat in those parts,while we sleep, raiseth in the brain animagination of some kindness shown. In sum,our dreams are the reverse of our wakingimaginations; the motion when we are awakebeginning at one end, and when we dream, atanother.The most difficult discerning of a man's dreamfrom his waking thoughts is, then, when bysome accident we observe not that we haveslept: which is easy to happen to a man full athan.html (10 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.fearful thoughts; and whose conscience is muchtroubled; and that sleepeth without thecircumstances of going to bed, or putting offhis clothes, as one that noddeth in a chair. Forhe that taketh pains, and industriously layshimself to sleep, in case any uncouth andexorbitant fancy come unto him, cannot easilythink it other than a dream. We read of MarcusBrutus (one that had his life given him byJulius Caesar, and was also his favorite, andnotwithstanding murdered him), how atPhilippi, the night before he gave battle toAugustus Caesar, he saw a fearful apparition,which is commonly related by historians as avision, but, considering the circumstances, onemay easily judge to have been but a shortdream. For sitting in his tent, pensive andtroubled with the horror of his rash act, it wasnot hard for him, slumbering in the cold, todream of that which most affrighted him;which fear, as by degrees it made him wake, soalso it must needs make the apparition bydegrees to vanish: and having no assurance thathe slept, he could have no cause to think it adream, or anything but a vision. And this is novery rare accident: for even they that beperfectly awake, if they be timorous andsuperstitious, possessed with fearful tales, andalone in the dark, are subject to the like fancies,and believe they see spirits and dead men'sghosts walking in churchyards; whereas it iseither their fancy only, or else the knavery ofsuch persons as make use of such superstitiousfear to pass disguised in the night to places theywould not be known to haunt. From thisignorance of how to distinguish dreams, andother strong fancies, from vision and sense, didarise the greatest part of the religion of theGentiles in time past, that worshipped satyrs,fauns, nymphs, and the like; and nowadays theopinion that rude people have of fairies, ghosts,and goblins, and of the power of witches. For,as for witches, I think not that their bes/leviathan.html (11 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.is any real power, but yet that they are justlypunished for the false belief they have that theycan do such mischief, joined with their purposeto do it if they can, their trade being nearer to anew religion than to a craft or science. And forfairies, and walking ghosts, the opinion of themhas, I think, been on purpose either taught, ornot confuted, to keep in credit the use ofexorcism, of crosses, of holy water, and othersuch inventions of ghostly men. Nevertheless,there is no doubt but God can make unnaturalapparitions: but that He does it so often as menneed to fear such things more than they fear thestay, or change, of the course of Nature, whichhe also can stay, and change, is no point ofChristian faith. But evil men, under pretext thatGod can do anything, are so bold as to sayanything when it serves their turn, though theythink it untrue; it is the part of a wise man tobelieve them no further than right reason makesthat which they say appear credible. If thissuperstitious fear of spirits were taken away,and with it prognostics from dreams, falseprophecies, and many other things dependingthereon, by which crafty ambitious personsabuse the simple people, men would be wouldbe much more fitted than they are for civilobedience. And this ought to be the work of theschools, but they rather nourish such doctrine.For (not knowing what imagination, or thesenses are) what they receive, they teach: somesaying that imaginations rise of themselves,and have no cause; others that they rise mostcommonly from the will; and that goodthoughts are blown (inspired) into a man byGod, and evil thoughts, by the Devil; or thatgood thoughts are poured (infused) into a manby God, and evil ones by the Devil. Some saythe senses receive the species of things, anddeliver them to the common sense; and thecommon sense delivers them over to the fancy,and the fancy to the memory, and the memoryto the judgement, like handing of things viathan.html (12 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.one to another, with many words makingnothing understood. The imagination that israised in man (or any other creature enduedwith the faculty of imagining) by words, orother voluntary signs, is that we generally callunderstanding, and is common to man andbeast. For a dog by custom will understand thecall or the rating of his master; and so willmany other beasts. That understanding which ispeculiar to man is the understanding not onlyhis will, but his conceptions and thoughts, bythe sequel and contexture of the names ofthings into affirmations, negations, and otherforms of speech: and of this kind ofunderstanding I shall speak hereafter.CHAPTER IIIOF THE CONSEQUENCE OR TRAIN OFIMAGINATIONSBY CONSEQUENCE, or train of thoughts, Iunderstand that succession of one thought toanother which is called, to distinguish it fromdiscourse in words, mental discourse.When a man thinketh on anything whatsoever,his next thought after is not altogether so casualas it seems to be. Not every thought to everythought succeeds indifferently. But as we haveno imagination, whereof we have not formerlyhad sense, in whole or in parts; so we have notransition from one imagination to another,whereof we never had the like before in oursenses. The reason whereof is this. All fanciesare motions within us, relics of those made inthe sense; and those motions that immediatelysucceeded one another in the sense continuealso together after sense: in so much as theformer coming again to take place and bepredominant, the latter followeth, by coherenceof the matter moved, in such manner as waterupon a plain table is drawn which way any iathan.html (13 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.part of it is guided by the finger. But because insense, to one and the same thing perceived,sometimes one thing, sometimes another,succeedeth, it comes to pass in time that in theimagining of anything, there is no certaintywhat we shall imagine next; only this is certain,it shall be something that succeeded the samebefore, at one time or another.This train of thoughts, or mental discourse, isof two sorts. The first is unguided, withoutdesign, and inconstant; wherein there is nopassionate thought to govern and direct thosethat follow to itself as the end and scope ofsome desire, or other passion; in which case thethoughts are said to wander, and seemimpertinent one to another, as in a dream. Suchare commonly the thoughts of men that are notonly without company, but also without care ofanything; though even then their thoughts areas busy as at other times, but without harmony;as the sound which a lute out of tune wouldyield to any man; or in tune, to one that couldnot play. And yet in this wild ranging of themind, a man may oft-times perceive the way ofit, and the dependence of one thought uponanother. For in a discourse of our present civilwar, what could seem more impertinent than toask, as one did, what was the value of a Romanpenny? Yet the coherence to me was manifestenough. For the thought of the war introducedthe thought of the delivering up the King to hisenemies; the thought of that brought in thethought of the delivering up of Christ; and thatagain the thought of the 30 pence, which wasthe price of that treason: and thence easilyfollowed that malicious question; and all this ina moment of time, for thought is quick.The second is more constant, as beingregulated by some desire and design. For theimpression made by such things as we desire,or fear, is strong and permanent, or (if it eviathan.html (14 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.for a time) of quick return: so strong it issometimes as to hinder and break our sleep.From desire ariseth the thought of some meanswe have seen produce the like of that which weaim at; and from the thought of that, thethought of means to that mean; and socontinually, till we come to some beginningwithin our own power. And because the end, bythe greatness of the impression, comes often tomind, in case our thoughts begin to wanderthey are quickly again reduced into the way:which, observed by one of the seven wise men,made him give men this precept, which is nowworn out: respice finem; that is to say, in allyour actions, look often upon what you wouldhave, as the thing that directs all your thoughtsin the way to attain it.The train of regulated thoughts is of two kinds:one, when of an effect imagined we seek thecauses or means that produce it; and this iscommon to man and beast. The other is, whenimagining anything whatsoever, we seek all thepossible effects that can by it be produced; thatis to say, we imagine what we can do with itwhen we have it. Of which I have not at anytime seen any sign, but in man only; for this isa curiosity hardly incident to the nature of anyliving creature that has no other passion butsensual, such as are hunger, thirst, lust, andanger. In sum, the discourse of the mind, whenit is governed by design, is nothing but seeking,or the faculty of invention, which the Latinscall sagacitas, and solertia; a hunting out of thecauses of some effect, present or past; or of theeffects of some present or past cause.Sometimes a man seeks what he hath lost; andfrom that place, and time, wherein he misses it,his mind runs back, from place to place, andtime to time, to find where and when he had it;that is to say, to find some certain and limitedtime and place in which to begin a method ofseeking. Again, from thence, his thoughts iathan.html (15 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.over the same places and times to find whataction or other occasion might make him loseit. This we call remembrance, or calling tomind: the Latins call it reminiscentia, as it werea re-conning of our former actions.Sometimes a man knows a place determinate,within the compass whereof he is to seek; andthen his thoughts run over all the parts thereofin the same manner as one would sweep a roomto find a jewel; or as a spaniel ranges the fieldtill he find a scent; or as a man should run overthe alphabet to start a rhyme.Sometimes a man desires to know the event ofan action; and then he thinketh of some likeaction past, and the events thereof one afteranother, supposing like events will follow likeactions. As he that foresees what will becomeof a criminal re-cons what he has seen followon the like crime before, having this order ofthoughts; the crime, the officer, the prison, thejudge, and the gallows. Which kind of thoughtsis called foresight, and prudence, orprovidence, and sometimes wisdom; thoughsuch conjecture, through the difficulty ofobserving all circumstances, be very fallacious.But this is certain: by how much one man hasmore experience of things past than another; byso much also he is more prudent, and hisexpectations the seldomer fail him. The presentonly has a being in nature; things past have abeing in the memory only; but things to comehave no being at all, the future being but afiction of the mind, applying the sequels ofactions past to the actions that are present;which with most certainty is done by him thathas most experience, but not with certaintyenough. And though it be called prudence whenthe event answereth our expectation; yet in itsown nature it is but presumption. For theforesight of things to come, which isprovidence, belongs only to him by whose viathan.html (16 of 145)4/5/2005 4:42:45 AM

Thomas Hobbes. Leviathan.they are to come. From him only, andsupernaturally, proceeds prophecy. The bestprophet naturally is the best guesser; and thebest guesser, he that is most versed and studiedin the matters he guesses at, for he hath mostsigns to guess by.A sign is the event antecedent of theconsequent; and contrarily, the consequent ofthe antecedent, when the like consequenceshave been observed before: and the oftenerthey have been observed, the less uncertain isthe sign. And therefore he that has mostexperience in any kind of business has mostsigns whereby to guess at the future time, andconsequently is the most prudent: and so muchmore prudent than he that is new in that kind ofbusiness, as not to be equalled by anyadvantage of natur

war, death. Lastly, the pacts and covenants, by which the parts of this body politic were at first made, set together, and united, resemble that fiat, or the Let us make man, pronounced by God in the Creation. To describe the nature of this artificial man, I will consider First,