Transcription

OXFORD WORLD’S CLASSICSThe Qur anA new translation byM. A. S. ABDEL HALEEM1

3Great Clarendon Street, Oxford ox2 6dpOxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford.It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship,and education by publishing worldwide inOxford New YorkAuckland Cape Town Dar es Salaam Hong Kong KarachiKuala Lumpur Madrid Melbourne Mexico City NairobiNew Delhi Shanghai Taipei TorontoWith offices inArgentina Austria Brazil Chile Czech Republic France GreeceGuatemala Hungary Italy Japan South Korea Poland PortugalSingapore Switzerland Thailand Turkey Ukraine VietnamOxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Pressin the UK and in certain other countriesPublished in the United Statesby Oxford University Press Inc., New York M. A. S. Abdel Haleem 2004, 2005The moral rights of the author have been assertedDatabase right Oxford University Press (maker)First published 2004First published, with corrections, as an Oxford World’s Classics paperback 2005All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press,or as expressly permitted by law, or under terms agreed with the appropriatereprographics rights organizations. Enquiries concerning reproductionoutside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department,Oxford University Press, at the address aboveYou must not circulate this book in any other binding or coverand you must impose this same condition on any acquirerBritish Library Cataloguing in Publication DataData availableLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataKoran. English.The Qur an / a new translation by M. A. S. Abdel Haleem.p. cm. –– (Oxford world’s classics)Originally published: 2004.Includes bibliographical references and index.I. Abdel Haleem, M. A. II. Title. III. Oxford world’s classics (Oxford University Press)BP109 2005297.1′22521––dc222004030574ISBN 0–19–283193–31Typeset in Ehrhardtby RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, SuffolkPrinted in Great Britain byClays Ltd, St Ives plc

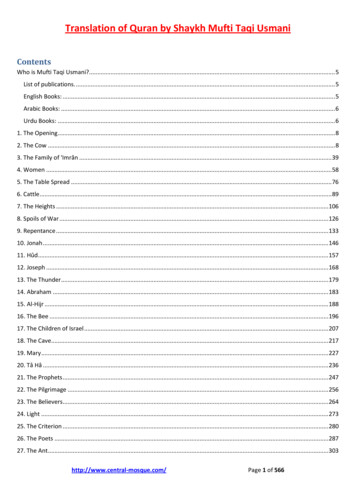

CONTENTSIntroductionThe Life of Muhammad and the Historical BackgroundThe Revelation of the Qur anThe Compilation of the Qur anThe Structure of the Qur an: Suras and AyasStylistic FeaturesIssues of InterpretationA Short History of English TranslationsThis TranslationixxxivxvxvixixxxixxvixxixA Chronology of the Qur anxxxviiSelect BibliographyxxxixMap of Arabia at the Time of the RevelationxliiiTHE QUR The Opening (Al-Fatiha)The Cow (Al-Baqara)The Family of Imran (Al- Imran)Women (Al-Nisa )The Feast (Al-Ma ida)Livestock (Al-An am)The Heights (Al-A raf )Battle Gains (Al-Anfal)Repentance (Al-Tawba)Jonah (Yunus)Hud (Hud)Joseph (Yusuf )Thunder (Al-Ra d )Abraham (Ibrahim)Al-Hijr (Al-Hijr)The Bee (Al-Nahl)The Night Journey (Al-Isra )The Cave (Al-Kahf )Mary 183191

.53.54.55.56.57.58.ContentsTa Ha (Ta Ha)The Prophets (Al-Anbiya )The Pilgrimage (Al-Hajj)The Believers (Al-Mu minun)Light (Al-Nur)The Differentiator (Al-Furqan)The Poets (Al-Shu ara )The Ants (Al-Naml)The Story (Al-Qasas)The Spider (Al- Ankabut)The Byzantines (Al-Rum)Luqman (Luqman)Bowing down in Worship (Al-Sajda)The Joint Forces (Al-Ahzab)Sheba (Saba )The Creator (Fatir)Ya Sin (Ya Sin)Ranged in Rows (Al-Saffat)Sad (Sad)The Throngs (Al-Zumar)The Forgiver (Ghafir)[Verses] Made Distinct (Fussilat)Consultation (Al-Shura)Ornaments of Gold (Al-Zukhruf )Smoke (Al-Dukhan)Kneeling (Al-Jathiya)The Sand Dunes (Al-Ahqaf )Muhammad (Muhammad)Triumph (Al-Fath)The Private Rooms (Al-Hujurat)Qaf (Qaf )Scattering [Winds] (Al-Dhariyat)The Mountain (Al-Tur)The Star (Al-Najm)The Moon (Al-Qamar)The Lord of Mercy (Al-Rahman)That which is Coming (Al-Waqi a)Iron (Al-Hadid)The Dispute 338340343345347350353356359362

.90.91.92.93.94.95.96.97.The Gathering [of Forces] (Al-Hashr)Women Tested (Al-Mumtahana)Solid Lines (Al-Saff )The Day of Congregation (Al-Jumu a)The Hypocrites (Al-Munafiqun)Mutual Neglect (Al-Taghabun)Divorce (Al-Talaq)Prohibition (Al-Tahrim)Control (Al-Mulk)The Pen (Al-Qalam)The Inevitable Hour (Al-Haqqa)The Ways of Ascent (Al-Ma arij)Noah (Nuh)The Jinn (Al-Jinn)Enfolded (Al-Muzzammil)Wrapped in his Cloak (Al-Muddaththir)The Resurrection (Al-Qiyama)Man (Al-Insan)[Winds] Sent Forth (Al-Mursalat)The Announcement (Al-Naba )The Forceful Chargers (Al-Nazi at)He Frowned ( Abasa)Shrouded in Darkness (Al-Takwir)Torn Apart (Al-Infitar)Those who Give Short Measure (Al-Mutaffifin)Ripped Apart (Al-Inshiqaq)The Towering Constellations (Al-Buruj)The Night-Comer (Al-Tariq)The Most High (Al-A la)The Overwhelming Event (Al-Ghashiya)Daybreak (Al-Fajr)The City (Al-Balad)The Sun (Al-Shams)The Night (Al-Layl)The Morning Brightness (Al-Duha)Relief (Al-Sharh)The Fig (Al-Tin)The Clinging Form (Al- Alaq)The Night of Glory 19420422423424425426427428429

110.111.112.113.114.IndexContentsClear Evidence (Al-Bayyina)The Earthquake (Al-Zalzala)The Charging Steeds (Al- Adiyat)The Crashing Blow (Al-Qari a)Striving for More (Al-Takathur)The Declining Day (Al- Asr)The Backbiter (Al-Humaza)The Elephant (Al-Fil)Quraysh (Quraysh)Common Kindnesses (Al-Ma un)Abundance (Al-Kawthar)The Disbelievers (Al-Kafirun)Help (Al-Nasr)Palm Fibre (Al-Masad)Purity [of Faith] (Al-Ikhlas)Daybreak (Al-Falaq)People 444445446447

I N T RO D U C T I O NThe Qur an is the supreme authority in Islam. It is the fundamental and paramount source of the creed, rituals, ethics, and lawsof the Islamic religion. It is the book that ‘differentiates’ betweenright and wrong, so that nowadays, when the Muslim world isdealing with such universal issues as globalization, the environment, combating terrorism and drugs, issues of medical ethics, andfeminism, evidence to support the various arguments is sought inthe Qur an. This supreme status stems from the belief that theQur an is the word of God, revealed to the Prophet Muhammad viathe archangel Gabriel, and intended for all times and all places.The Qur an was the starting point for all the Islamic sciences:Arabic grammar was developed to serve the Qur an, the study ofArabic phonetics was pursued in order to determine the exact pronunciation of Qur anic words, the science of Arabic rhetoric wasdeveloped in order to describe the features of the inimitable style ofthe Qur an, the art of Arabic calligraphy was cultivated throughwriting down the Qur an, the Qur an is the basis of Islamic law andtheology; indeed, as the celebrated fifteenth-century scholarand author Suyuti said, ‘Everything is based on the Qur an’. Theentire religious life of the Muslim world is built around the text ofthe Qur an. As a consequence of the Qur an, the Arabic languagemoved far beyond the Arabian peninsula, deeply penetrating manyother languages within the Muslim lands––Persian, Turkish, Urdu,Indonesian, and others. The first sura (or section) of the Qur an,al-Fatiha, which is an essential part of the ritual prayers, is learnedand read in Arabic by Muslims in all parts of the world, and manyother verses and phrases in Arabic are also incorporated into thelives of non-Arabic-speaking Muslims.Muslim children start to learn portions of the Qur an by heart intheir normal schooling: the tradition of learning the entire Qur an byheart started during the lifetime of the Prophet and continues to thepresent day. A person attaining this distinction becomes known as ahafiz, and this is still a prerequisite for admission to certain religiousschools in Muslim countries. Nowadays the Qur an is recited anumber of times daily on the radio and television in the Muslim

xIntroductionworld, and some Muslim countries devote a broadcasting channelfor long hours daily exclusively to the recitation and study ofthe Qur an. Muslims swear on the Qur an for solemn oaths in thelawcourts and in everyday life.The Life of Muhammad and the Historical BackgroundMuhammad was born in Mecca in about the year 570 ce. Thereligion of most people in Mecca and Arabia at the beginning ofMuhammad’s lifetime was polytheism. Christianity was found inplaces, notably in Yemen, and among the Arab tribes in the northunder Byzantine rule; Judaism too was practised in Yemen, and inand around Yathrib, later renamed Madina (Medina), but the vastmajority of the population of Arabia were polytheists. They believedin a chief god Allah, but saw other deities as mediators betweenthem and him: the Qur an mentions in particular the worship ofidols, angels, the sun, and the moon as ‘lesser’ gods. The Hajjpilgrimage to the Ka ba in Mecca, built, the Qur an tells us, byAbraham for the worship of the one God, was practised but thattoo had become corrupted with polytheism. Mecca was thus animportant centre for religion, and for trade, with the caravans thattravelled via Mecca between Yemen in the south and Syria in thenorth providing an important source of income. There was no central government. The harsh desert conditions brought competitionfor scarce resources, and enforced solidarity within each tribe, butthere was frequent fighting between tribes. Injustices were practisedagainst the weaker classes, particularly women, children, slaves, andthe poor.Few hard facts are known about Muhammad’s childhood. It isknown that his father Abdullah died before he was born and hismother Amina when he was 6 years old; that his grandfather AbdulMuttalib then looked after him until, two years later, he too died. Atthe age of 8, Muhammad entered the guardianship of his uncle AbuTalib, who took him on a trade journey to the north when he was12 years old. In his twenties, Muhammad was employed as a traderby a wealthy and well-respected widow fifteen years his senior namedKhadija. Impressed by his honesty and good character, she proposedmarriage to him. They were married for over twenty-five years untilKhadija’s death when Muhammad was some 49 years old. Khadija

Introductionxiwas a great support to her husband. After his marriage, Muhammadlived in Mecca, where he was a respected businessman andpeacemaker.Muhammad was in the habit of taking regular periods of retreatand reflection in the Cave of Hira outside Mecca. This is where thefirst revelation of the Qur an came to him in 610 ce, when he was40 years old. This initiated his prophethood. The Prophet wasinstructed to spread the teachings of the revelations he received tohis larger family and beyond. However, although a few believed inhim, the majority, especially the powerful, resented his calling themto abandon their gods. After all, many polytheist tribes came toMecca on the pilgrimage, and the leaders feared that the newreligion would threaten their own prestige and economic prosperity.They also felt it would disturb the social order, as it was quiteoutspoken in its preaching of equality between all people and itscondemnation of the injustices done to the weaker members of thesociety.The hostility of the Meccans soon graduated from gentle ridiculeto open conflict and the persecution of Muhammad’s followers,many of whom Muhammad sent, from the fifth year of hispreaching, to seek refuge with the Christian king of Abyssinia(Ethiopia). The remaining Muslims continued to be pressurized bythe Meccans, who instituted a total boycott against the Prophet’sclan, refusing to allow any social or economic dealings with them. Inthe middle of this hardship, Muhammad’s wife, Khadija, and hisuncle, Abu Talib, died, so depriving the Prophet of their great support. This year became known as the Year of Grief. However, eventswere soon to take a change for the better. The Prophet experiencedthe event known as the Night Journey and Ascension to Heaven,during which Muhammad was accompanied by Gabriel from thesanctuary of Mecca first to Jerusalem and then to Heaven. Soonafterwards, some people from Yathrib, a town some 400 km north ofMecca, met Muhammad when they came to make the pilgrimageand some of these accepted his faith; the following year morereturned from Yathrib, pledged to support him, and invited him andhis community to seek sanctuary in Yathrib. The Muslims began tomigrate there, soon followed by the Prophet himself, narrowly escaping an attempt to assassinate him. This move to Yathrib, known asthe Migration (Hijra), was later adopted as the start of the Muslim

xiiIntroductioncalendar. Upon arrival in Yathrib, Muhammad built the first mosquein Islam, and he spent most of his time there, teaching and remoulding the characters of the new Muslims from unruly tribesmen intoa brotherhood of believers. Guided by the Qur an, he acted asteacher, judge, arbitrator, adviser, consoler, and father-figure to thenew community. One of the reasons the people of Yathrib invited theProphet to migrate there was the hope that he would be a goodarbitrator between their warring tribes, as indeed proved to bethe case.Settled in Yathrib, Muhammad made a pact of mutual solidaritybetween the immigrants (muhajirun) and the Muslims of Yathrib,known as the ansar––helpers. This alliance, based not on tribal buton religious solidarity, was a departure from previous social norms.Muhammad also made a larger pact between all the tribes of Yathrib,that they would all support one another in defending the city againstattack. Each tribe would be equal under this arrangement, includingthe Jews, and free to practise their own religions.Islam spread quickly in Yathrib, which became known as Madinatal-Nabi (the City of the Prophet) or simply Medina (city). Thiswas the period in which the revelations began to contain legislationon all aspects of individual and communal life, as for the first timethe Muslims had their own state. In the second year at Medina(ah 2) a Qur anic revelation came allowing the Muslims to defendthemselves militarily (22: 38–41) and a number of battles againstthe Meccan disbelievers and their allies took place near Medina,starting with Badr shortly after this revelation, Uhud the followingyear, and the Battle of the Trench in ah 5. The Qur an commentson these events.In ah 6 the Meccans prevented the Muslims from undertaking apilgrimage to Mecca. Negotiations followed, where the Muslimsaccepted that they would return to Medina for the time being butcome back the following year to finish the pilgrimage. A truce wasagreed for ten years. However, in ah 8 a Meccan ally broke thetruce. The Muslims advanced to attack Mecca, but its leadersaccepted Islam and surrendered without a fight. From this pointonwards, delegations started coming from all areas of Arabia to meetthe Prophet and make peace with him.In ah 10 the Prophet made his last pilgrimage to Mecca and gavea farewell speech on the Mount of Mercy, declaring equality and

Introductionxiiisolidarity between all Muslims. By this time the whole Arabianpeninsula had accepted Islam and all the warring tribes were unitedin one state under one head. Soon after his return to Medina in theyear 632 ce (ah 10), the Prophet received the last revelation of theQur an and, shortly thereafter, died. His role as leader of the Islamicstate was taken over by Abu Bakr (632–4 ce), followed by Umar(634–44) and Uthman (644–56), who oversaw the phenomenalspread of Islam beyond Arabia. They were followed by Ali (656–61).These four leaders are called the Rightly Guided Caliphs.After Ali, the first political dynasty of Islam, the Umayyads(661–750), came into power. There had, however, been some frictionwithin the Muslim community on the question of succession to theProphet after his death: the Shi is, or supporters of Ali, felt that Aliand not Abu Bakr was the appropriate person to take on the mantleof head of the community. They believed that the leadership shouldthen follow the line of descendants of the Prophet, through theProphet’s cousin and son-in-law Ali. After Ali’s death, they adoptedhis sons Hasan and then Husayn as their leader or imam. After thelatter’s death in the Battle of Karbala in Iraq (680 ce/ah 61),Husayn took on a special significance for the Shi i community:he is mourned every year on the Day of Ashura. Some Shi i believethat the Prophet’s line ended with the seventh imam Isma il (d. 762ce/ah 145); others believe that the line continued as far as atwelfth imam in the ninth century.The Islamic state stretched by the end of its first century fromSpain, across North Africa, to Sind in north-west India. In latercenturies it expanded further still to include large parts of East andWest Africa, India, Central and South-East Asia, and parts of Chinaand southern Europe. Muslim migrants like the Turks and Tartarsalso spread into parts of northern Europe, such as Kazan andPoland. After the Second World War there was another major influxof Muslims into all areas of the world, including Europe, America,and Australia, and many people from these continents converted tothe new faith. The total population of Muslims is now estimated atmore than one billion (of which the great majority are Sunni), aboutone-fifth of the entire population of the world,1 and Islam is said tobe the fastest-growing religion in the world.1See http://www.iiie.net/Intl/PopStats.html.

xivIntroductionThe Revelation of the Qur anMuhammad’s own account survives of the extraordinary circumstances of the revelation, of being approached by an angel whocommanded him: ‘Read in the name of your Lord.’ 2 When heexplained that he could not read,3 the angel squeezed him strongly,repeating the request twice, and then recited to him the first twolines of the Qur an.4 For the first experience of revelation Muhammad was alone in the cave, but after that the circumstances in whichhe received revelations were witnessed by others and recorded.When he experienced the ‘state of revelation’, those around himwere able to observe his visible, audible, and sensory reactions. Hisface would become flushed and he would fall silent and appear as ifhis thoughts were far away, his body would become limp as if he wereasleep, a humming sound would be heard about him, and sweatwould appear on his face, even on winter days. This state would lastfor a brief period and as it passed the Prophet would immediatelyrecite new verses of the Qur an. The revelation could descend onhim as he was walking, sitting, riding, or giving a sermon, and therewere occasions when he waited anxiously for it for over a month inanswer to a question he was asked, or in comment on an event: thestate was clearly not the Prophet’s to command. The Prophet and hisfollowers understood these signs as the experience accompanyingthe communication of Qur anic verses by the Angel of Revelation(Gabriel), while the Prophet’s adversaries explained them as magicor as a sign of his ‘being possessed’.It is worth noting that the Qur an has itself recorded all claims andattacks made against it and against the Prophet in his lifetime, butfor many of Muhammad’s contemporaries the fact that the first wordof the Qur an was an imperative addressed to the Prophet (‘Read’)These words appear at the beginning of Sura 96 of the Qur an.Moreover, until the first revelation came to him in the cave, Muhammad was notknown to have composed any poem or given any speech. The Qur an employs this fact inarguing with the unbelievers: ‘If God had so willed, I would not have recited it to you,nor would He have made it known to you. I lived a whole lifetime among you before itcame to me. How can you not use your reason?’ (10: 16). Among other things this istaken by Muslims as proof of the Qur an’s divine source.4 The concepts of ‘reading’, ‘learning/knowing’, and ‘the pen’ occur six times inthese two lines. As Muslim writers on education point out (e.g. S. Qutb, Fi Dhilalal-Qur an (Cairo, 1985), vi. 3939), the revelation of the Qur an began by talking aboutreading, teaching, knowing, and writing.23

Introductionxvlinguistically made the authorship of the text outside Muhammad.Indeed, this mode is maintained throughout the Qur an: it talks tothe Prophet or talks about him; never does the Prophet pass comment or speak for himself. The Qur an describes itself as a scripturethat God ‘sent down’ to the Prophet (the expression ‘sent down’, inits various forms, is used in the Qur an well over 200 times) and, inArabic, this word conveys immediately, and in itself, the conceptthat the origin of the Qur an is from above and that Muhammad ismerely a recipient. God is the one to speak in the Qur an: Muhammad is addressed, ‘Prophet’, ‘Messenger’, ‘Do’, ‘Do not do’, ‘Theyask you . . .’, ‘Say’ (the word ‘say’ is used in the Qur an well over300 times). Moreover, the Prophet is sometimes even censured inthe Qur an.5 His status is unequivocally defined as ‘Messenger’(rasul).The first revelation consisted of the two lines which began theQur an and the mission of the Prophet, after which he had no furtherexperience of revelation for some while. Then another short piecewas revealed, and between then and shortly before the Prophet’sdeath in 632 ce at the age of 63 (lunar years), the whole text ofthe Qur an was revealed gradually, piece by piece, in varyinglengths, giving new teaching or commenting on events or answeringquestions, according to circumstances.The Compilation of the Qur anWith every new revelation, the Prophet would recite the newaddition to the Qur an to those around him, who would eagerly learnit and in turn recite it to others. Throughout his mission the Prophetrepeatedly recited the Qur an to his followers and was meticulous inensuring that the Qur an was recorded,6 even in the days of persecution. As each new piece was revealed, Gabriel instructed the Prophetas to where it should go in the final corpus. An inner circle of hisfollowers wrote down verses of the Qur an as they learned them from9: 43; 80: 1–11.The word qur an means ‘reading/reciting’ and came to refer to ‘the text which isread/recited’. The Muslim scripture often calls itself kitab ‘writing’, and this came torefer to ‘the written book’. Thus the significance of uttering and writing the revealedscripture is emphasized from the very beginning of Islam, and is locked in the verynouns that designate the Qur an.56

xviIntroductionthe Prophet and there are records of there being a total of twentynine scribes for this. By the end of the Prophet’s life (632 ce) theentire Qur an was written down in the form of uncollated pieces. Inaddition, most followers learned parts of it by heart and manylearned all of it from the Prophet over years spent in his company.7They also learned from the Prophet the correct ordering of theQur anic material.8 They belonged to a cultural background that hada long-standing tradition of memorizing literature, history, andgenealogy.The standard Muslim account is that, during the second year afterthe Prophet’s death (633 ce) and following the Battle of Yamama, inwhich a number of those who knew the Qur an by heart died, it wasfeared that with the gradual passing away of such men there was adanger of some Qur anic material being lost. Therefore the first caliphand successor to the Prophet, Abu Bakr, ordered that a written copy ofthe whole body of Qur anic material as arranged by the Prophet andmemorized by the Muslims should be made and safely stored withhim.9 About twelve years later, with the expansion of the Islamic state,the third caliph, Uthman, ordered that a number of copies should bemade from this to be distributed to different parts of the Muslimworld as the official copy of the Qur an, which became known as the Uthmanic Codex. This codex has been recognized throughoutthe Muslim world for the last fourteen centuries as the authenticdocument of the Qur an as revealed to the Prophet Muhammad.The Structure of the Qur an: Suras and AyasAs explained above, Qur anic revelation came to the Prophetgradually, piece by piece, over a period of twenty-three years.Material was placed in different sections, not in chronological orderSee Subhi al-Salih, Mabahith fi Ulum al-Qur an (Beirut, 1981), 65–7.During the last twenty-five years there have been some views contesting thistraditional history of the Qur an and maintaining that it was canonized at a later date.The reader can consult a survey and discussion of these views in Angelika Neuwirth,‘The Qur an and History: A Disputed Relationship’, Journal of Qur anic Studies, 5/1(2003), 1–18. Also see H. Motzki, ‘The Collection of the Qur an: A Reconsideration ofWestern Views in Light of Recent Methodological Developments’, Der Islam (2001),2–34.9 The written fragments were another important source for the collation of this‘canonical’ document.78

Introductionxviiof revelation, but according to how they were to be read by theProphet and believers. The Qur an is divided into 114 sections ofvarying lengths, the longest (section 2) being around twenty pages inArabic, the shortest (sections 108 and 112) being one line in Arabiceach. These sections are each known in Arabic as sura, and we willuse this word to refer to them.Each sura (with the exception of Sura 9) begins with ‘In theName of God, the Lord of Mercy, the Giver of Mercy’, and a suraconsists of a number of verses each known in Arabic as an aya.Again, an aya can run into several lines and consist of severalsentences, or it can be one single word, but it normally ends inArabic with a rhyme.The titles of the suras require some explanation. Many surascombine several subjects within them, as will be explained belowunder ‘Stylistic Features’, and the titles were allocated on the basisof either the main theme within the sura, an important event thatoccurs in the sura, or a significant word that appears within it. Theintroductions to the suras in this translation are intended to help thereader in this respect.Meccan and Medinan SurasThe Qur anic material revealed to the Prophet in Mecca is distinguished by scholars from the material that came after theMigration (Hijra) to Medina. In the Meccan period, the Qur an wasconcerned mainly with the basic beliefs in Islam––the unity of Godas evidenced by His ‘signs’ (ayat),10 the prophethood of Muhammad,and the Resurrection and Final Judgement––and these themes arereiterated again and again for emphasis and to reinforce Qur anicteachings. These issues were especially pertinent to the Meccans.Most of them believed in more than one god. The Qur an refers tothis as shirk (partnership): the sharing of several gods in the creationand government of the universe. The reader will note the frequentuse of ‘partnership’ and ‘associate’ throughout the Qur an. TheMeccans also initially denied the truth of Muhammad’s message,and the Qur an refers to earlier prophets (many of them also mentioned in the Bible, for instance Noah, Abraham, Jacob, Joseph,10See e.g. 25: 1–33; 27: 59 ff.; 30: 17 ff.; 41: 53.

xviiiIntroductionMoses, and Jesus),11 in order both to reassure the Prophet and hisfollowers that they will be saved, and to warn their opponents thatthey will be punished. The Qur an stresses that all these prophetspreached the same message and that the Qur an was sent to confirmthe earlier messages. It states that Muslims should believe in all ofthem without making any distinction between them (2: 285). TheMeccans likewise could not conceive of the Resurrection of theDead. In the Meccan suras the Qur an gives arguments from embryology and from nature in general (36: 76–83; 56: 47–96; 22: 5–10) toexplain how the Resurrection can and will take place; the Qur anseeks always to convince by reference to history, to what happened toearlier generations, by explanations from nature, and through logic.In the Medinan suras, by which time the Muslims were no longerthe persecuted minority but an established community with theProphet as its leader, the Qur an begins to introduce laws to governthe Muslim community with regard to marriage, commerce andfinance, international relations, war and peace. Examples of thesecan be found in Suras 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and 9. This era also witnessed theemergence of a new group, the munafiqun or hypocrites, who pretended to profess Islam but were actually working against the Islamicstate, and these ‘hypocrites’ are a frequent theme in the Medinansuras. We also see here discussion of the ‘People of the Book’ withparticular reference to Jewish and Christian communities, both thosecontemporary with the Prophet and those in the past. It will be seenthat the Qur an tends to speak of groups or classes of people ratherthan individuals.Throughout the Meccan and Medinan suras the beliefs andmorals of the Qur an are put forward and emphasized, and theseform the bulk of Qur anic material; the percentage of strictly legaltexts in the Qur an is very small indeed. The Qur an contains some6,200 verses and out of these only 100 deal with ritual practices, 70verses discuss personal laws, 70 verses civil laws, 30 penal laws, and20 judiciary matters and testimony.12 Moreover, these tend to dealwith general principles such as justice, kindness, and charity, ratherthan detailed laws: even legal matters are explained in language thatappeals to the emotions, conscience, and belief in God. In versesdealing with retaliation (2: 178–9), once the principles are established1112See e.g. 2: 136; 3: 84–5; 6: 83–90; 42: 13.A. Khallaf, A Concise History of Islamic Legislation [Arabic] (Kuwait, 1968), 28–9.

Introductionxixthe text goes on to soften t

the Quran, the art of Arabic calligraphy was cultivated through writing down the Quran, the Quran is the basis of Islamic law and theology; indeed, as the celebrated fifteenth-century scholar and author Suyuti said, ‘Everything is based on the Quran’. The entire religious life of the Muslim worl