Transcription

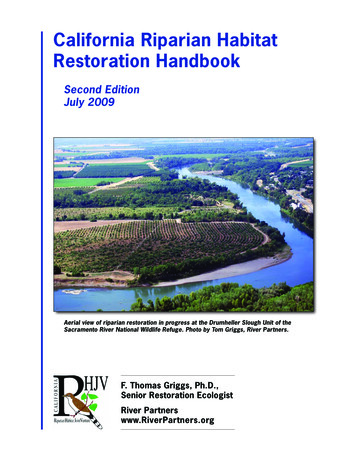

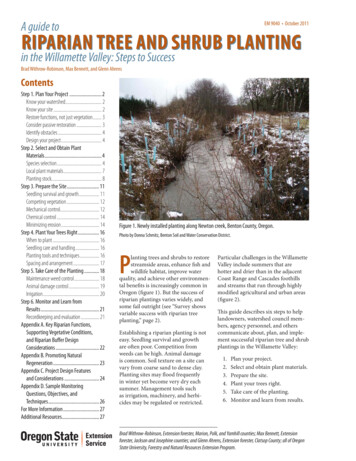

A guide toEM 9040 October 2011RIPARIAN TREE AND SHRUB PLANTINGin the Willamette Valley: Steps to SuccessBrad Withrow-Robinson, Max Bennett, and Glenn AhrensContentsStep 1. Plan Your Project.2Know your watershed. 2Know your site. 2Restore functions, not just vegetation. 3Consider passive restoration. 3Identify obstacles. 4Design your project. 4Step 2. Select and Obtain PlantMaterials.4Species selection. 4Local plant materials. 7Planting stock. 8Step 3. Prepare the Site.11Seedling survival and growth. 11Competing vegetation. 12Mechanical control. 12Chemical control. 14Minimizing erosion. 14Step 4. Plant Your Trees Right. 16When to plant. 16Seedling care and handling. 16Planting tools and techniques. 16Spacing and arrangement. 17Step 5. Take Care of the Planting. 18Maintenance weed control. 18Animal damage control. 19Irrigation. 20Step 6. Monitor and Learn fromResults.21Recordkeeping and evaluation. 21Appendix A. Key Riparian Functions,Supporting Vegetative Conditions,and Riparian Buffer DesignConsiderations.22Appendix B. Promoting NaturalRegeneration.23Appendix C. Project Design Featuresand Considerations.24Appendix D. Sample MonitoringQuestions, Objectives, andTechniques.26For More Information.27Additional Resources.27Figure 1. Newly installed planting along Newton creek, Benton County, Oregon.Photo by Donna Schmitz, Benton Soil and Water Conservation District.Planting trees and shrubs to restorestreamside areas, enhance fish andwildlife habitat, improve waterquality, and achieve other environmental benefits is increasingly common inOregon (figure 1). But the success ofriparian plantings varies widely, andsome fail outright (see “Survey showsvariable success with riparian treeplanting,” page 2).Establishing a riparian planting is noteasy. Seedling survival and growthare often poor. Competition fromweeds can be high. Animal damageis common. Soil texture on a site canvary from coarse sand to dense clay.Planting sites may flood frequentlyin winter yet become very dry eachsummer. Management tools suchas irrigation, machinery, and herbicides may be regulated or restricted.Particular challenges in the WillametteValley include summers that arehotter and drier than in the adjacentCoast Range and Cascades foothillsand streams that run through highlymodified agricultural and urban areas(figure 2).This guide describes six steps to helplandowners, watershed council members, agency personnel, and otherscommunicate about, plan, and implement successful riparian tree and shrubplantings in the Willamette Valley:1.2.3.4.5.6.Plan your project.Select and obtain plant materials.Prepare the site.Plant your trees right.Take care of the planting.Monitor and learn from results.Brad Withrow-Robinson, Extension forester, Marion, Polk, and Yamhill counties; Max Bennett, Extensionforester, Jackson and Josephine counties; and Glenn Ahrens, Extension forester, Clatsop County; all of OregonState University, Forestry and Natural Resources Extension Program.

STEP 1. PLANYOUR PROJECTKnow your watershedYour project goals should reflectconditions and needs in your localwatershed. Identify what is missingor most in need of enhancement, andset priorities accordingly. In westernOregon, for example, warm streamtemperature is commonly identifiedas the primary water-quality issue, soproviding shade to maintain cool waterconditions is often a priority.Figure 2. Willamette Valley ecoregion.Image from The Oregon Conservation Strategy. 2006.Salem, OR: Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.Reproduced by permission.Survey shows variablesuccess with ripariantree plantingSlightly fewer than half of 105 riparian tree-planting projects in westernOregon achieved tree survival ratesof 75% or more, according to a 2002study by the Oregon WatershedEnhancement Board.In 40% of the projects in the study,fewer than half the trees survived.Projects installed under theConservation Reserve EnhancementProgram were more successfulthan projects funded by grants. Thestudy’s authors attributed this difference to the greater use of sitepreparation, postplanting maintenance, and tree protection underthe program.Source: Anderson, M., andG. Graziano. 2002. StatewideSurvey of OWEB Riparian andStream Enhancement Projects.Salem, OR: Oregon WatershedEnhancement Board.2Begin planning by reviewing watershed assessments from your localwatershed council or larger public orprivate landowners in your watershed(find your local watershed councilat http://www.oregon.gov/OWEB/WSHEDS/wsheds councils list.shtml).Many watershed councils have alreadyidentified key constraints and opportunities in watersheds or subbasins (e.g.,elevated stream temperatures or lack oflarge wood).Know your siteOnce you understand watershedconditions and needs, examine yoursite. Identify specific challenges (e.g.,frequent flooding [figure 3], poorlydrained soils, abundance and type ofweeds, or likely animal damage) thatmight be serious constraints to a successful planting.Next, determine what could beenhanced at your site to contributeto overall watershed health. Considerthings you might try to change (e.g.,amount of shade, bank stability, orlivestock use near the stream). Somechanges might be easy; others mightbe difficult or expensive. Some actionswill have almost immediate benefits;improvements from other actionswon’t be evident for years or decades.Make sure any difficult and expensiveactions line up with your priorities.Be sure to consult others. Identify partners in conservation organizations orother agencies who might be able tohelp identify needs and opportunitiesat your site (figure 4).Checklist for Step 1: Plan your projectTime and thought at this stage will lead to a better, more cost-effective projectin the long run. Assess needs for the riparian area in the context of watershed conditionsand priorities. What is missing or most in need of enhancement? Observe site conditions to determine what actions will address identifiedneeds and have the greatest potential for success. Set goals based on what will help restore key functions in the futurerather than what is thought to have prevailed in the past. Consider promoting natural regeneration of trees and shrubs and otherpassive restoration approaches as well as planting. Try to get the greatestvalue for your investment. Think about possible obstacles, such as a mismatch between project sizeand budget, equipment availability, and your time, skills, and commitment. Is there a good chance of success? Develop a site-specific design that addresses local watershed issues,is appropriate for site conditions, and can be accomplished withavailable resources.Riparian Tree and Shrub Planting in the Willamette Valley

Figure 3. Flooding of a young riparian planting on the North YamhillRiver, Yamhill County, Oregon.Figure 4. Assess current site conditions to determine benefits alreadybeing provided, what is needed, and establishment challenges.Photo by Amie Loop-Frison, Yamhill Soil and Water Conservation District.Photo by Tara Davis, Calapooia Watershed Council.Restore functions, notjust vegetationConditions before European settlement are sometimes used as a guidefor desirable riparian conditions. Butrestoration to presettlement conditionsis often difficult or inappropriate. Fewaccurate or detailed records of thoseconditions exist, and existing recordsare snapshots of single moments intime, with no assurance that they arerepresentative of a longer time frame.Also, because riparian ecosystems arecomplex and change over time, there isno “natural” condition for a given area.Ecologists recommend restoring orenhancing important riparian functions (figure 5), not just vegetationconditions. For example, developmentacross the Willamette Valley has led toloss and degradation of many habitats,including once-extensive networks ofriparian forests, prairies, and savannas. This, in turn, reduced plant andanimal populations. One functionalgoal is to improve habitat by restoringor enhancing conditions that are critical to survival of a species or group ofspecies. See Appendix A (page 22) formore examples of riparian functions.Riparian vegetation provides manyimportant functions for aquatic habitats. For example, restoration projectsdesigned to aid salmon populationsoften focus on establishing tree species that create shade, reduce streamRiparian Tree and Shrub Planting in the Willamette ValleySurfacefilteringLarge, woodydebrisShade for streamSubsurfacefilteringLitterfallStream bank andchannel stabilitySediment retentionFigure 5. Important functions of a riparian area include shade for the stream, stream bankstability, woody debris for the stream, sediment retention, litter for aquatic organisms in thestream, water filtering, aquatic habitat, and riparian wildlife habitat.temperatures, and drop leaves andinsects into the stream. Plantings willeventually provide large wood, which isimportant for modifying stream channels and creating in-stream habitats.Riparian areas are also important terrestrial habitats. A well-developedshrub layer provides foraging and nesting sites for migratory songbirds. Largetrees are needed to provide nestingor foraging sites for large birds, suchas herons and pileated woodpeckers.Large trees take time to develop, butyou may accelerate their growth byplanting fast-growing species, spacingthem far apart, and controlling weedsand other competition. You can alsoprovide some functions normally provided by large trees through interimactions, such as installing nestingboxes (for wood ducks and screechowls) or platforms (for osprey).Consider passiverestorationConsider whether your site will beable to grow and develop as you desirewithout actively planting it (a passiverestoration approach). For example,you may be able to meet tree establishment goals by encouraging naturalregeneration of species already present and reproducing on the site (seeAppendix B, page 23). Perhaps the onlyaction needed is to remove grazinglivestock, weed competition, or intensive cultivation.3

Identify obstaclesIt is important to assess operationalconstraints, identify problems, andresolve conflicts during the planningphase. Think about and discuss thefollowing questions with advisors andorganizational partners: How much money, time,and energy are available forthis project? Is the budget adequate for thesize of the project? Do you have a good understanding of demands on resourcesto accomplish key activitiesthroughout the project (fromplanning, to planting, to weedcontrol and maintenance)? Canyou realistically meet thosedemands in a timely way, considering your other commitments,health, and access to and skill inusing equipment and tools? Ifnot, is there money in the budgetto hire help?Checklist for Step 2:Select and obtain plantmaterialsSpecies, source, and stock type areimportant considerations. Identify species that will provide the key riparian functionsyou identified during planning. Choose species that are welladapted to your site. Considertolerance to shade, flooded orwaterlogged soils, and drought. Select locally adapted, genetically diverse seedlings or otherplant materials that fit your siteconditions, management constraints, and budget. Plan ahead. Order seedlingsand other types of plantingstock well in advance.4 What conflicts might arise withadjacent land uses (e.g., farmingor grazing), and how can thesebe resolved? Is there good access to the planting site, and can you move in anyneeded equipment or supplies? Does the site location allow frequent visits for monitoring andmaintenance, or will you visit thesite only occasionally? How will you determineproject success? What arethe consequences of anunsuccessful planting?The scale of the project is also animportant consideration. Small projects (e.g., dozens to a few hundredtrees) allow use of a wider range oftechniques, such as hand-cuttingcompeting vegetation, that mightbe prohibitively expensive on largerprojects. As the project’s size andcomplexity increase, so does the needfor cost-effective methods of sitepreparation, planting, and vegetationcontrol. Balance the scale of your project with the budget, time, and otherresources available.STEP 2. SELECTAND OBTAINPLANT MATERIALSSpecies selectionYour plant selections will affect theappearance and function of your riparian planting for decades. Trees andshrubs must be able to survive andprosper when planted and also providethe functions you need in the future.Tables 1 and 2 list characteristics ofnative trees and shrubs.Site adaptationChoose species that are well adaptedto site conditions. Moisture—eitherthe lack or excess of—is often the mostimportant factor in both planting success and long-term survival. Considerhow the local climate and soils affectmoisture, and select species on thebasis of moisture needs and flood andDesign your projectAlthough it is helpful to look at otherplans and projects, be sure to design ariparian planting that is specific to yoursite, reflects identified goals, and can beaccomplished with available resources.Your design will need to address manyfeatures: Width and position of theplanting Species to plant and type ofplanting materials Plant spacing and arrangement Access for people and equipment (for maintenance andmonitoring) Fencing or other protection fromlivestock and wildlifeYou also need to decide how to preparethe site for planting, how to protectseedlings from weed competition,and how to maintain the planting.The following sections provide moreinformation on these topics. Also seeAppendix C (page 24) for additionalproject design considerations.drought tolerance. Start by identifying native species growing on similarsites nearby.Conifers, such as Douglas-fir or western redcedar, are often a priority forriparian plantings in mountainousareas because they provide dense shadeand durable, large wood. However,many conifers are not as well adaptedto riparian areas in the WillametteValley that are flood prone or poorlydrained and should be selectedwith caution.Tolerance to floods and poordrainageAreas along the stream channel andbanks as well as sloughs and swalesmay be subject to frequent or prolonged flooding. Species selected forthese areas must have high flood tolerance. Black cottonwood, bigleaf maple,western redcedar, red alder, whitealder, and Oregon ash tolerate flooding(figure 6).Riparian Tree and Shrub Planting in the Willamette Valley

Table 1. Characteristics of riparian and bottomland tree species for the Willamette Valley.Tolerance toSpeciesFloodingDroughtShadeCommentsBigleaf mapleAcer macrophyllumMediumMediumHighMedium-lived tree. Provides early season food forseedeaters and good structural habitat.Black cottonwoodPopulus trichocarpaHighLowLowLarge, fast-growing tree. Prefers moist, well-drainedsoils. Well-suited for shade and bank stabilization.Popular nesting platform for some birds. Roots wellfrom cuttings.Douglas-firPseudotsuga menziesiiLowMediumMediumTall, long-lived tree. Provides dense shade, durabledead wood, and structural elements. Does nottolerate flooding.MediumMediumHighOregon ashFraxinus latifoliaHighMediumMedium toHighOregon white oakQuercus garryanaHigh toMediumHighLowSlow-growing, medium-height tree. Tolerates poorlydrained, heavy soils. Wood ducks and other wildlife eatits acorns.Ponderosa pinePinus ponderosaMediumHighLowLarge, long-lived tree. Moderate growth rate. Providesdurable dead wood and structural elements. NativeWillamette Valley race is highly tolerant of both poorlydrained and droughty soils.White alderAlnus rhombifoliaHighLow toMediumLowFast-growing, medium-height tree. The more commonalder in the Willamette Valley and other interior valleys.More tolerant than red alder of poorly drained soils andwarm Valley climate. Nitrogen fixer.Red alderAlnus rubraHighLowLowFast-growing, medium-height tree. Likes moisture, butgood drainage. Often struggles on poorly drained sitesand in Willamette Valley climate. Nitrogen fixer.Western redcedarThuja plicataHighLowHighLikes moisture, but good drainage. Grows in WillametteValley riparian areas but may struggle. Premium sourceof large, woody debris.Grand firAbies grandisFast-growing tree. Source of woody debris.Slow-growing, medium-height tree. Tolerates poorlydrained, heavy clay soils. Older trees provide cavities.A related but often separate problem issoil drainage. Soils on higher terracesin the Willamette Valley often haveheavy, fine-textured (clayey) soils withvery poor drainage and poor aerationduring the rainy season, regardless ofwhether they flood regularly (table 3).These are essentially wetland soils.Plants on these soils are subjected tosaturated conditions for much longerperiods than during surface flooding.redcedar and red alder, may seemappropriate but often grow poorly onheavy (clayey) soils and in hot summerconditions. Trees that do best underthese conditions include Oregon ash,Oregon white oak, white alder, blackcottonwood, and the native WillametteValley race of ponderosa pine. Shrubsthat do well include Douglas spirea,snowberry, red-osier dogwood,and willow.Poorly drained soils may be morelimiting than floods for plant selection, and planting the wrong specieson saturated sites is a common causeof planting failure around the valley.Plants associated with moist conditions in the mountains, such as westernAreas along natural river levies andhigher edges of floodplains will alsoflood, although less frequently and forshorter durations. These sites may havewell-drained soils and are suitable fora larger group of plants with mediumflood tolerance.Riparian Tree and Shrub Planting in the Willamette ValleyFigure 6. Black cottonwood is well suited forgiving shade and stabilizing stream banks.Photo by Brad Withrow-Robinson, Oregon StateUniversity.5

Table 2. Characteristics of riparian and bottomland shrub and small tree species for the Willamette Valley.Tolerance to6SpeciesFloodingDroughtShadeCommentsCascara buckthornRhamnus purshianaMediumMediumMediumSmall tree with cherry-like berries favored bymany birds.Douglas hawthornCrataegus douglasiiHighMediumMedium toHighSmall tree. Produces berries in late summer.Douglas spireaSpiraea douglasiiHighMediumLowElderberry, blueSambucus caeruleaMediumMediumMedium toHighElderberry, redSambucus racemosaHighMediumHighMock orangePhiladelphus lewisiiMediumMediumMediumTall understory shrub.Oregon crabappleMalus fuscaHighMediumMediumLarge, thicket-forming shrub or small tree.OsoberryOemleria cerasiformisLow toMediumMediumHighPacific ninebarkPhysocarpus capitatusMedium toHighLowMedium toHighTall understory shrub. Roots from cuttings.Red-osier dogwoodCornus stoloniferaHighLowMediumTall understory shrub. Roots from cuttings.SalmonberryRubus spectabilisHighMediumHighServiceberryAmelanchier alnifoliaMediumMediumMediumSnowberrySymphoricarpos albusMediumMediumHighLow shrub. Roots from cuttings.ThimbleberryRubus parviflorusLowLowHighCommon mountain riparian species sometimes seen inWillamette Valley. Produces berries in late summer.Vine mapleAcer circinatumLowLowHighCommon mountain riparian species sometimes seen inWillamette Valley.WillowSalix spp.HighLowLowSome willows are tree size; others are large shrubs. Rootvery well from cuttings. Well suited to bank stabilizationand bioengineering projects.Low, dense shrub. Provides good cover. Spreading. Rootswell from cuttings.Large, vigorous shrub. Berries ripen in late summer.Medium shrub. Produces berries in early summer.Medium shrub. Blooms very early. Fruits ripen inlate spring.Common mountain riparian species sometimes seen inWillamette Valley. Produces berries in late summer.Large, thicket-forming shrub.Riparian Tree and Shrub Planting in the Willamette Valley

Table 3. Common wetland soils of the Willamette Valley.Wetland (hydric) soils form when saturation, flooding, or ponding occur for long enough during the growing season that anaerobic conditionsdevelop in the upper part of the soil. Anaerobic conditions are challenging for many species and often a limiting factor for tree and shrub growth.This table shows Willamette Valley soils listed as hydric. There are other somewhat poorly drained to poorly drained soils (e.g., Amity silt loam)that, while not hydric, can limit species selection and growth of trees and shrubs.NameLandformAwbrig silty clay loamTerracesBashaw clayFloodplains and terracesBrenner silt loamFloodplains and swalesConcord silt loamTerracesConser silty clay loamTerracesCourtney gravely silty clay loamStream terracesCove silty clay loamFloodplainsDayton silt loamTerracesGrande Ronde silty clay loamTerracesHuberly silty loamSwales and terracesPanther silty clay loamLow hills, slumpsVerboort silty clay loamFloodplainsWapato silty clay loamFloodplainsWaldo silty clay loamFloodplainsWhiteson silt loamFloodplainsSource: USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service; survey area version date: 12-23-2006. ro.html)Drought toleranceThe Willamette Valley has hot, drysummer weather, and moisture stressis often a limiting factor in seedlingsurvival. Sites close to major rivers canactually be quite dry for new seedlings.These riverbanks and levies often havesandy or gravely soils with low nutrient-and moisture-holding capacity, andthey dry out rapidly each summer oncethe rains stop.Although mature black cottonwoodtrees thrive along the sandy banks ofthe Willamette River, this species hasrelatively low drought tolerance andmay be difficult to establish on suchsites until its roots reach moisture deepin the soil. In some situations, youcan offset this issue with weed controland irrigation.Riparian Tree and Shrub Planting in the Willamette ValleyShade toleranceFast-growing riparian tree species,such as willow, cottonwood, and alder,quickly colonize disturbed areas afterfloods. But these trees are intolerantof shade and not suitable for planting in the understory of existing trees.Oregon ash, bigleaf maple, grand fir,western redcedar, and many shrubspecies are tolerant of shade and moresuitable for such areas (tables 1 and 2).Shade tolerance also comes into play asyoung trees grow and begin to competewith each other for light and otherresources. Slower-growing and smallertree species will tend to fall behind ingrowth; if these species are not shadetolerant, they will likely die and disappear from the stand. Such competitionis part of a natural process but can leadto less diversity and a simpler standstructure than planned for or desired.Address this issue with thoughtful species selection, appropriatespacing and planting arrangements(see Appendix C, page 24), and selective thinning.Local plant materialsMany species you select for yourplanting likely grow in many locations in Oregon and North America.For instance, white alder is plentifulin southwest Oregon, and ponderosapine is abundant in central Oregon.However, plants of the same species from different environments canperform very differently on your site.It is important to find seedlings andplanting stock grown from WillametteValley sources. Buying from a localnursery is not necessarily enough; it iswhere the seed (or other parent material) comes from that counts, not theplace where seedlings are raised.See “Seed sources and genetic issues”(page 10) for more information.7

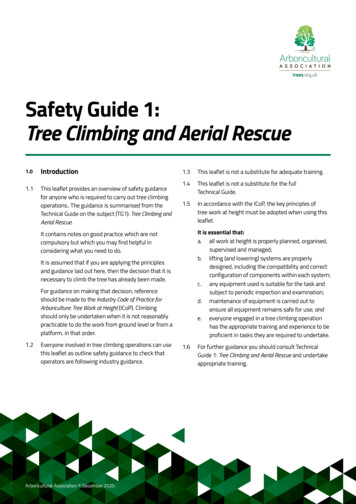

Table 4. Characteristics of seedling and stock types for riparian plantings.Stock typeBare rootSize(stem caliperand height)Unit cost rangeComments0.1–0.5 caliper8–24 inches 0.15– 0.650.05–0.3 caliper6–20 inches 0.25– 0.80Container: 1- to5-gallon pots or 3- to4-inch by 18- to 24inch PVC pipe0.2–2.0 caliper12–60 inches 1.00– 10.00Fall to springplanting. Requiresless skill in handling.Survives on droughtysites. Expensiveto plant.Cutting: cane or whip0.25–1.0 caliper12–72 inches 0.20– 0.30 perfoot or labor andtransportPresoaking advised.Can cut from localsites. Toleratesflooding. Doesnot tolerate earlyweed competition.Grows rapidly.Cutting: pole1.0–4.0 caliper48–96 inchesBall and burlap(B&B)1.5–5.0 caliper36–240 inchesContainer plugs 25.00– 250.00Wide availability.Winter planting.Roots vulnerableto drying. Requiresextra care inhandling.Fall to springplanting. Requiresless skill in handling.Easier for rocky sites.Expensive. Instantlandscape.Planting stockSeveral types of seedlings and stocktypes are used in riparian plantings(table 4). Consider these characteristicswhen selecting a stock type: AvailabilityHandling sensitivityCostEase of transport and plantingSurvival and growth potentialIn general, bigger is better. Biggerstock is less likely to be overtoppedby competing vegetation and recoversbetter when browsed. However, it isalso more expensive to buy and plant.Ensure that bigger stock has an adequate root system to support the largeshoot system.Bare-root seedlings (figure 7) aregrown in nursery beds, usually for2 years, and then dug and plantedduring the winter dormant season.They perform well if they receiveproper care and are the foundation ofmany riparian restoration projects.Common designations for bare-rootseedlings: 2-0—2-year-old tree grown onlyin a nursery bed 1-1—2-year-old tree grown1 year in a nursery bed and 1 yearin a lower-density transplant bed Plug-1—bare-root seedling thatstarted out as a small containerseedling and was transplantedto an outdoor nursery bed andgrown for 1 yearThe 1-1s tend to be larger than 2-0sand have denser, more fibrous rootsystems. They also cost more. Plug-1seedlings have characteristics of container and bare-root seedlings andwell-developed, fibrous root systems.They are more expensive than otherbare-root seedlings.Advantages of bare-root seedlings:Figure 7. Examples of different stock types. From left: Douglas-fir container plug, 2-0, 1-1, andponderosa pine plug-1.Photos from Rose, R., and D.L. Haase. 2006. Guide to Reforestation in Oregon. Corvallis, OR: Oregon State UniversityCollege of Forestry. Reproduced by permission.8 Low cost Easy to transport Wide availability of many foresttree (and some shrub) speciesRiparian Tree and Shrub Planting in the Willamette Valley

Disadvantages of bare-root seedlings: Narrow planting window (winterdormant season) Requires skill during planting Greater sensitivity to improperhandling and planting (e.g., rootdrying and other damage)See Selecting and Buying QualitySeedlings, OSU Extension publicationEC 1196 (http://extension.oregonstate.edu/catalog), for more informationabout stock types.Container stock (figure 8) is grown incontainers and planted with soil intactaround the roots. Small containerseedlings commonly are referred toas plugs. Sizes range from “Styro-10s”(10 cubic inches of soil in the plug) to1-gallon pots to large plugs grown in24-inch-long PVC pipe.Figure 8. Large container stock at Stone Nursery, Central Point, Oregon.Photo by Max Bennett, Oregon State University.Advantages of container stock: Longer planting window (fallthrough early spring) Less skill needed during planting Less potential for damage duringhandling and planting Easier than bare-root seedlings toplant on rocky or otherwise difficult sites (plugs) Better survival on droughtysites (plugs)Disadvantages of container stock: More difficult to transport to andaround the site as size increases Potential for introducing weeds High costCuttings (figure 9) are dormant sections of hardwood trees and shrubs.They have no leaves or roots. Largecuttings are called whips, canes, orpoles. Cuttings are used in the fieldand in nursery production of containerstock. When conditions are right, cuttings root after planting; willow andcottonwood root better than otherspecies. Cuttings are available in sizesfrom 1 to 10 feet long. For best results,generally select young (i.e., currentyear and 1-year-old) wood and soakcuttings before planting.Riparian Tree and Shrub Planting in the Willamette ValleyFigure 9. Cottonwood and willow cuttings, ready for planting. Notethat the two cuttings in the foreground have begun to root.Photo by Chris Van Schaack.Advantages of cuttings: Relatively low cost Easy to plant Flood toleranceDisadvantages of cuttings: Greater vulnerability to dryconditions High sensitivity to weed competition during establishment Potential narrowing of geneticdiversity (each rooted cutting isa clone)Ball-and-burlap (B&B) stock hasa large ball of soil around the rootsystem held in place with a burlapwrap. These tend to be much larger,much more expensive trees that aregenerally inappropriate for most restoration situations but may be used inpark settings and other green spaces inor near urban areas.Advantages of ball-and-burlap stock: Provide an “instant tree” Good survival and growthDisadvantages of ball-and-burlapstock: High cost More difficult to plant than otherstock types9

Many commercial forest nurseries inthe Pacific Northwest grow plants suitable for riparian restoration projects.The popularity of these projects, andthe demand for plantin

easy. Seedling survival and growth are often poor. Competition from weeds can be high. Animal damage is common. Soil texture on a site can vary from coarse sand to dense clay. Planting sites may flood frequently in winter yet become very dry each summer. Management tools such as irrigation, m