Transcription

Memoryi

MemoryWritingsThought Force in Business and Everyday LifeThe Law of the New ThoughtNuggets of the New ThoughtMemory Culture: The Science of Observing, Remembering and RecallingDynamic Thought or The Law of Vibrant EnergyThought Vibration or the Law of Attraction in the Thought WorldPractical Mind‑ReadingPractical Psychomancy and Crystal GazingThe Mind Building of a ChildThe Secret of Mental MagicMental FascinationSelf‑Healing by Thought ForceMind‑Power: The Law of Dynamic MentationPractical Mental InfluenceReincarnation and the Law of KarmaThe Inner ConsciousnessThe Secret of SuccessMemory: How to Develop, Train and Use ItSubconscious and the Superconscious Planes of MindSuggestion and Auto‑SuggestionThe Art of ExpressionThe Art of Logical ThinkingThe New Psychology: Its Message, Principles and PracticeThe WillThought‑CultureHuman Nature: Its Inner States and Outer FormsMind and Body or Mental States and Physical ConditionsTelepathy: Its Theory, Facts and ProofThe Crucible of Modern ThoughtThe Psychology of SalesmanshipThe Psychology of SuccessScientific ParenthoodThe Message of the New ThoughtYour Mind and How to Use ItThe Mastery of BeingMind‑Power: The Secret of Mental MagicThe New Psychology of HealingNew Thought: Its History and Principlesii

MemoryHow to Develop, Train and Use It1909William Walker Atkinson1862–1932信YOGeBooks: Hollister, MO2013:09:06:17:04:43iii

MemoryCopyrightYOGeBooks by Roger L. Cole, Hollister, MO 65672 2010 YOGeBooks by Roger L. ColeAll rights reserved. Electronic edition published 2010isbn: 978-1-61183-084-2 (pdf)isbn: 978-1-61183-085-9 (epub)www.yogebooks.comiv

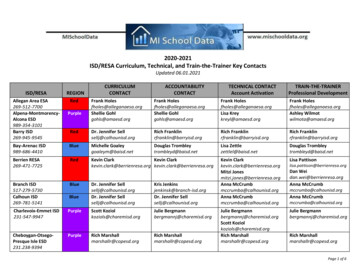

ContentsChapter I Memory: Its ImportanceChapter II Cultivation Of The MemoryChapter III Celebrated Cases of MemoryChapter IV Memory SystemsChapter V The Subconscious Record‑FileChapter VI AttentionChapter VII AssociationChapter VIII Phases of MemoryChapter IX Training the EyeChapter X Training the EarChapter XI How to Remember NamesChapter XII How to Remember FacesChapter XIII How to Remember PlacesChapter XIV How to Remember NumbersChapter XV How to Remember MusicChapter XVI How to Remember OccurrencesChapter XVII How to Remember FactsChapter XVIII How to Remember Words, EtcChapter XIX How to Remember Books, Plays, Tales, EtcChapter XX General Instructionsv

Memoryvi

Memory1

Memory2

Memory: Its ImportanceChapter IMemory: Its ImportanceIt needs very little argument to convince the average thinkingperson of the great importance of memory, although eventhen very few begin to realize just how important is thefunction of the mind that has to do with the retention of mentalimpressions. The first thought of the average person when heis asked to consider the importance of memory, is its use in theaffairs of every‑day life, along developed and cultivated lines, ascontrasted with the lesser degrees of its development. In short,one generally thinks of memory in its phase of “a good memory”as contrasted with the opposite phase of “a poor memory.” Butthere is a much broader and fuller meaning of the term thanthat of even this important phase.It is true that the success of the individual in his every‑daybusiness, profession, trade or other occupation depends verymaterially upon the possession of a good memory. His value inany walk in life depends to a great extent upon the degree ofmemory he may have developed. His memory of faces, names,facts, events, circumstances and other things concerning hisevery‑day work is the measure of his ability to accomplish histask. And in the social intercourse of men and women, thepossession of a retentive memory, well stocked with available3

Memoryfacts, renders its possessor a desirable member of society. Andin the higher activities of thought, the memory comes as aninvaluable aid to the individual in marshalling the bits andsections of knowledge he may have acquired and passing themin review before his cognitive faculties—thus does the soulreview its mental possessions. As Alexander Smith has said: “Aman’s real possession is his memory; in nothing else is he rich;in nothing else is he poor.” Richter has said: “Memory is theonly paradise from which we cannot be driven away. Grant butmemory to us, and we can lose nothing by death.” Lactantiussays: “Memory tempers prosperity, mitigates adversity, controlsyouth, and delights old age.”But even the above phases of memory represent but asmall segment of its complete circle. Memory is more than“a good memory”—it is the means whereby we performthe largest share of our mental work. As Bacon has said: “Allknowledge is but remembrance.” And Emerson: “Memory is aprimary and fundamental faculty, without which none othercan work: the cement, the bitumen, the matrix in which theother faculties are embedded. Without it all life and thoughtwere an unrelated succession.” And Burke: “There is no facultyof the mind which can bring its energy into effect unless thememory be stored with ideas for it to look upon.” And Basile:“Memory is the cabinet of imagination, the treasury of reason,the registry of conscience, and the council chamber of thought.”Kant pronounced memory to be “the most wonderful of thefaculties.” Kay, one of the best authorities on the subject hassaid, regarding it: “Unless the mind possessed the power oftreasuring up and recalling its past experiences, no knowledgeof any kind could be acquired. If every sensation, thought, oremotion passed entirely from the mind the moment it ceasedto be present, then it would be as if it had not been; and itcould not be recognized or named should it happen to return.Such an one would not only be without knowledge,withoutexperience gathered from the past,—but without purpose,4

Memory: Its Importanceaim, or plan regarding the future, for these imply knowledgeand require memory. Even voluntary motion, or motionfor a purpose, could have no existence without memory, formemory is involved in every purpose. Not only the learning ofthe scholar, but the inspiration of the poet, the genius of thepainter, the heroism of the warrior, all depend upon memory.Nay, even consciousness itself could have no existence withoutmemory for every act of consciousness involves a changefrom a past state to a present, and did the past state vanishthe moment it was past, there could be no consciousness ofchange. Memory, therefore, may be said to be involved in allconscious existence—a property of every conscious being!In the building of character and individuality, the memoryplays an important part, for upon the strength of theimpressions received, and the firmness with which they areretained, depends the fibre of character and individuality.Our experiences are indeed the stepping stones to greaterattainments, and at the same time our guides and protectorsfrom danger. If the memory serves us well in this respect we aresaved the pain of repeating the mistakes of the past, and mayalso profit by remembering and thus avoiding the mistakesof others. As Beattie says: “When memory is preternaturallydefective, experience and knowledge will be deficient inproportion, and imprudent conduct and absurd opinion arethe necessary consequence.” Bain says: “A character retaining afeeble hold of bitter experience, or genuine delight, and unableto revive afterwards the impression of the time is in reality thevictim of an intellectual weakness under the guise of a moralweakness. To have constantly before us an estimate of the thingsthat affect us, true to the reality, is one precious condition forhaving our will always stimulated with an accurate reference toour happiness. The thoroughly educated man, in this respect,is he that can carry with him at all times the exact estimateof what he has enjoyed or suffered from every object that hasever affected him, and in case of encounter can present to5

Memorythe enemy as strong a front as if he were under the genuineimpression. A full and accurate memory, for pleasure or forpain, is the intellectual basis both of prudence as regards self,and sympathy as regards others.”So, we see that the cultivation of the memory is far more thanthe cultivation and development of a single mental faculty—itis the cultivation and development of our entire mental being—the development of our selves.To many persons the words memory, recollection, andremembrance, have the same meaning, but there is a greatdifference in the exact shade of meaning of each term. Thestudent of this book should make the distinction between theterms, for by so doing he will be better able to grasp the variouspoints of advice and instruction herein given. Let us examinethese terms.Locke in his celebrated work, the “Essay Concerning HumanUnderstanding” has clearly stated the difference between themeaning of these several terms. He says: “Memory is the powerto revive again in our minds those ideas which after imprinting,have disappeared, or have been laid aside out of sight—whenan idea again recurs without the operation of the like objecton the external sensory, it is remembrance; if it be sought afterby the mind, and with pain and endeavor found, and broughtagain into view, it is recollection.” Fuller says, commenting onthis: “Memory is the power of reproducing in the mind formerimpressions, or percepts. Remembrance and Recollection arethe exercise of that power, the former being involuntary orspontaneous, the latter volitional. We remember because wecannot help it but we recollect only through positive effort.The act of remembering, taken by itself, is involuntary. In otherwords, when the mind remembers without having tried toremember, it acts spontaneously. Thus it may be said, in thenarrow, contrasted senses of the two terms, that we rememberby chance, but recollect by intention, and if the endeavor be6

Memory: Its Importancesuccessful that which is reproduced becomes, by the very effortto bring it forth, more firmly intrenched in the mind than ever.”But the New Psychology makes a little different distinctionfrom that of Locke, as given above. It uses the word memorynot only in his sense of “The power to revive, etc.,” but also inthe sense of the activities of the mind which tend to receive andstore away the various impressions of the senses, and the ideasconceived by the mind, to the end that they may be reproducedvoluntarily, or involuntarily, thereafter. The distinction betweenremembrance and recollection, as made by Locke, is adoptedas correct by The New Psychology.It has long been recognized that the memory, in all ofits phases, is capable of development, culture, training andguidance through intelligent exercise. Like my other faculty ofmind, or physical part, muscle or limb, it may be improved andstrengthened. But until recent years, the entire efforts of thesememory‑developers were directed to the strengthening of thatphase of the memory known as “recollection,” which, you willremember, Locke defined as an idea or impression “sought afterby the mind, and with pain and endeavor found, and broughtagain into view.” The New Psychology goes much further thanthis. While pointing out the most improved and scientificmethods for “recollecting” the impressions and ideas of thememory, it also instructs the student in the use of the propermethods whereby the memory may be stored with clear anddistinct impressions which will, thereafter, flow naturally andinvoluntarily into the field of consciousness when the mind isthinking upon the associated subject or line of thought; andwhich may also be “re‑collected” by a voluntary effort with farless expenditure of energy than under the old methods andsystems.You will see this idea carried out in detail, as we progress withthe various stages of the subject, in this work. You will see thatthe first thing to do it to find something to remember; then toimpress that thing clearly and distinctly upon the receptive7

Memorytablets of the memory; then to exercise the remembrancein the direction of bringing out the stored‑away facts of thememory; then to acquire the scientific methods of recollectingspecial items of memory that may be necessary at some specialtime. This is the natural method in memory cultivation, asopposed to the artificial systems that you will find mentionedin another chapter. It is not only development of the memory,but also development of the mind itself in several of its regionsand phases of activity. It is not merely a method of recollecting,but also a method of correct seeing, thinking and remembering.This method recognizes the truth of the verse of the poet, Pope,who said: “Remembrance and reflection how allied! What thinpartitions sense from thought divide!”8

Chapter IICultivation Of The MemoryThis book is written with the fundamental intention andidea of pointing out a rational and workable methodwhereby the memory may be developed, trained andcultivated. Many persons seem to be under the impressionthat memories are bestowed by nature, in a fixed degree orpossibilities, and that little more can be done for them—inshort, that memories are born, not made. But the fallacyof any such idea is demonstrated by the investigations andexperiments of all the leading authorities, as well as by theresults obtained by persons who have developed and cultivatedtheir own memories by individual effort without the assistanceof an instructor. But all such improvement, to be real, mustbe along certain natural lines and in accordance with the wellestablished laws of psychology, instead of along artificial linesand in defiance of psychological principles. Cultivation of thememory is a far different thing from “trick memory,” or feats ofmental legerdemain if the term is permissible.Kay says: “That the memory is capable of indefiniteimprovement, there can be no manner of doubt; but withregard to the means by which this improvement is to beeffected mankind are still greatly in ignorance.” Dr. Noah9

MemoryPorter says: “The natural as opposed to the artificial memorydepends on the relations of sense and the relations of thought,the spontaneous memory of the eye and the ear availing itselfof the obvious conjunctions of objects which are furnishedby space and time, and the rational memory of those highercombinations which the rational faculties superinduce uponthose lower. The artificial memory proposes to substitute forthe natural and necessary relations under which all objectsmust present and arrange themselves, an entirely new set ofrelations that are purely arbitrary and mechanical, whichexcite little or no other interest than that they are to aid usin remembering. It follows that if the mind tasks itself to thespecial effort of considering objects under these artificialrelations, it will give less attention to those which have a directand legitimate interest for itself.” Granville says: “The defectsof most methods which have been devised and employed forimproving the memory, lies in the fact that while they serve toimpress particular subjects on the mind, they do not renderthe memory, as a whole, ready or attentive.” Fuller says: “Surelyan art of memory may be made more destructive to naturalmemory than spectacles are to eyes.” These opinions of the bestauthorities might be multiplied indefinitely—the consensus ofthe best opinion is decidedly against the artificial systems, andin favor of the natural ones.Natural systems of memory culture are based upon thefundamental conception so well expressed by Helvetius,several centuries ago, when he said: “The extent of the memorydepends, first, on the daily use we make of it; secondly, uponthe attention with which we consider the objects we wouldimpress upon it; and, thirdly, upon the order in which werannge our ideas.” This then is the list of the three essentialsin the cultivation of the memory: (1) Use and exercise; reviewand practice; (2) Attention and Interest; and (3) IntelligentAssociation.10

Cultivation Of The MemoryYou will find that in the several chapters of this book dealingwith the various phases of memory, we urge, first, last, andall the time, the importance of the use and employment ofthe memory, in the way of employment, exercise, practiceand review work. Like any other mental faculty, or physicalfunction, the memory will tend to atrophy by disuse, andincrease, strengthen and develop by rational exercise andemployment within the bounds of moderation. You develop amuscle by exercise; you train any special faculty of the mind inthe same way; and you must pursue the same method in thecase of the memory, if you would develop it. Nature’s laws areconstant, and bear a close analogy to each other. You will alsonotice the great stress that we lay upon the use of the facultyof attention, accompanied by interest. By attention you acquirethe impressions that you file away in your mental record‑fileof memory. And the degree of attention regulates the depth,clearness and strength of the impression. Without a goodrecord, you cannot expect to obtain a good reproduction ofit. A poor phonographic record results in a poor reproduction,and the rule applies in the case of the memory as well. Youwill also notice that we explain the laws of association, andthe principles which govern the subject, as well as themethods whereby the proper associations may be made. Everyassociation that you weld to an idea or an impression, servesas a cross‑reference in the index, whereby the thing is found byremembrance or recollection when it is needed. We call yourattention to the fact that one’s entire education depends for itsefficiency upon this law of association. It is a most importantfeature in the rational cultivation of the memory, while at thesame time being the bane of the artificial systems. Naturalassociations educate, while artificial ones tend to weaken thepowers of the mind, if carried to any great length.There is no Royal Road to Memory. The cultivation of thememory depends upon the practice along certain scientificlines according to well established psychological laws. Those11

Memorywho hope for a sure “short cut” will be disappointed, for nonesuch exists. As Halleck says: “The student ought not to bedisappointed to find that memory is no exception to the ruleof improvement by proper methodical and long continuedexercise. There is no royal road, no short cut, to the improvementof either mind or muscle. But the student who follows the ruleswhich psychology has laid down may know that he is walkingin the shortest path, and not wandering aimlessly about. Usingthese rules, he will advance much faster than those withoutchart, compass, or pilot. He will find mnemonics of extremelylimited use. Improvement comes by orderly steps. Methodsthat dazzle at first sight never give solid results.”The student is urged to pay attention to what we haveto say in other chapters of the book upon the subjects ofattention and association. It is not necessary to state herethe particulars that we mention there. The cultivation of theattention is a prerequisite for good memory, and deficiency inthis respect means deficiency not only in the field of memorybut also in the general field of mental work. In all branchesof The New Psychology there is found a constant repetitionof the injunction to cultivate the faculty of attention andconcentration. Halleck says: “Haziness of perception lies at theroot of many a bad memory. If perception is definite, the firststep has been taken toward insuring a good memory. If the firstimpression is vivid, its effect upon the brain cells is more lasting.All persons ought to practice their visualizing power. This willreact upon perception and make it more definite. Visualizingwill also form a brain habit of remembering things pictorially,and hence more exactly.”The subject of association must also receive its proper shareof attention, for it is by means of association that the storedaway records of the memory may be recovered or recollected.As Blackie says: “Nothing helps the mind so much as order andclassification. Classes are few, individuals many: to know theclass well is to know what is most essential in the character of12

Cultivation Of The Memorythe individual, and what burdens the memory least to retain.”And as Halleck says regarding the subject of association byrelation: “Whenever we can discover any relation between facts,it is far easier to remember them. The intelligent law of memorymay be summed up in these words: Endeavor to link by somethought relation each new mental acquisition to an old one.Bind new facts to other facts by relations of similarity, causeand effect, whole and part, or by any logical relation, and weshall find that when an idea occurs to us, a host of related ideaswill flow into the mind. If we wish to prepare a speech or writean article on any subject, pertinent illustrations will suggestthemselves. The person whose memory is merely contiguouswill wonder how we think of them.”In your study for the cultivation of the memory, along thelines laid down in this book, you have read the first chapterthereof and have informed yourself thoroughly regarding theimportance of the memory to the individual, and what a largepart it plays in the entire work of the mind. Now carefully readthe third chapter and acquaint yourself with the possibilitiesin the direction of cultivating the memory to a high degree,as evidenced by the instances related of the extreme caseof development noted therein. Then study the chapter onmemory systems, and realize that the only true method is thenatural method, which requires work, patience and practice—then make up your mind that you will follow this plan as faras it will take you. Then acquaint yourself with the secret ofmemory—the subconscious region of the mind, in whichthe records of memory are kept, stored away and indexed,and in which the little mental office‑boys are busily at work.This will give you the key to the method. Then take up thetwo chapters on attention, and association, respectively, andacquaint yourself with these important principles. Then studythe chapter on the phases of memory, and take mental stockof yourself, determining in which phase of memory you arestrongest, and in which you need development. Then read the13

Memorytwo chapters on training the eye and ear, respectively—youneed this instruction. Then read over the several chapters onthe training of the special phases of the memory, whether youneed them or not—you may find something of importancein them. Then read the concluding chapter, which gives yousome general advice and parting instruction. Then return tothe chapters dealing with the particular phases of memoryin which you have decided to develop yourself, studying thedetails of the instruction carefully until you know every pointof it. Then, most important of all‑get to work. The rest is a matterof practice, practice, practice, and rehearsal. Go back to thechapters from time to time, and refresh your mind regardingthe details. Re‑read each chapter at intervals. Make the bookyour own, in every sense of the word, by absorbing its contents.14

Chapter IIICelebrated Cases of MemoryIn order that the student may appreciate the marvelousextent of development possible to the memory, we havethought it advisable to mention a number of celebratedcases, past and present. In so doing we have no desire to holdup these cases as worthy of imitation, for they are exceptionaland not necessary in every‑day life. We mention them merelyto show to what wonderful extent development along theselines is possible.In India, in the past, the sacred books were committed tomemory, and handed down from teacher to student, for ages.And even to‑day it is no uncommon thing for the student tobe able to repeat, word for word, some voluminous religiouswork equal in extent to the New Testament. Max Muller statesthat the entire text and glossary of Panini’s Sanscrit grammar,equal in extent to the entire Bible, were handed down orallyfor several centuries before being committed to writing. Thereare Brahmins to‑day who have committed to memory, andwho can repeat at will, the entire collection of religious poemsknown as the Mahabarata, consisting of over 300,000 slokas orverses. Leland states that, “the Slavonian minstrels of the presentday have by heart with remarkable accuracy immensely long15

Memoryepic poems. I have found the same among Algonquin Indianswhose sagas or mythic legends are interminable, and yet arecommitted word by word accurately. I have heard in Englandof a lady ninety years of age whose memory was miraculous,and of which extraordinary instances are narrated by herfriends. She attributed it to the fact that when young she hadbeen made to learn a verse from the Bible every day, and thenconstantly review it. As her memory improved, she learnedmore, the result being that in the end she could repeat frommemory any verse or chapter called for in the whole Scripture.”It is related that Mithridates, the ancient warrior‑king, knewthe name of every soldier in his great army, and conversedfluently in twenty‑two dialects. Pliny relates that Charmidescould repeat the contents of every book in his large library.Hortensius, the Roman orator, had a remarkable memorywhich enabled him to retain and recollect the exact words ofhis opponent’s argument, without making a single notation. Ona wager, he attended a great auction sale which lasted over anentire day, and then called off in their proper order every objectsold, the name of its purchaser, and the price thereof. Seneca issaid to have acquired the ability to memorize several thousandproper names, and to repeat them in the order in which theyhad been given him, and also to reverse the order and call offthe list backward. He also accomplished the feat of listeningto several hundred persons, each of whom gave him a verse;memorizing the same as they proceeded; and then repeatingthem word for word in the exact order of their delivery andthen reversing the process, with complete success. Eusebiusstated that only the memory of Esdras saved the HebrewScriptures to the world, for when the Chaldeans destroyed themanuscripts Esdras was able to repeat them, word by word tothe scribes, who then reproduced them. The Mohammedanscholars are able to repeat the entire text of the Koran, letterperfect. Scaliger committed the entire text of the Iliad and theOdyssey, in three weeks. Ben Jonson is said to have been able16

Celebrated Cases of Memoryto repeat all of his own works from memory, with the greatestease.Bulwer could repeat the Odes of Horace from memory.Pascal could repeat the entire Bible, from beginning to end, aswell as being able to recall any given paragraph, verse, line, orchapter. Landor is said to have read a book but once, when hewould dispose of it, having impressed it upon his memory, tobe recalled years after, if necessary. Byron could recite all of hisown poems. Buffon could repeat his works from beginning toend. Bryant possessed the same ability to repeat his own works.Bishop Saunderson could repeat the greater part of Juvenaland Perseus, all of Tully, and all of Horace. Fedosova, a Russianpeasant, could repeat over 25,000 poems, folk‑songs, legends,fairy‑tales, war stories, etc., when she was over seventy yearsof age. The celebrated “Blind Alick,” an aged Scottish beggar,could repeat any verse in the Bible called for, as well as theentire text of all the chapters and books. The newspapers, a fewyears ago, contained the accounts of a man named Clark wholived in New York City. He is said to have been able to give theexact presidential vote in each State of the Union since the firstelection. He could give the population in every town of any sizein the world either present or in the past providing there was arecord of the same. He could quote from Shakespeare for hoursat a time beginning at any given point in any play. He couldrecite the entire text of the Diad in the original Greek.The historical case of the unnamed Dutchman is known toall students of memory. This man is said to have been able totake up a fresh newspaper; to read it all through, including theadvertisements; and then to repeat its contents, word for word,from beginning to end. On one occasion he is said to haveheaped wonder upon wonder, by repeating the contents ofthe paper backward, beginning with the last word and endingwith the first. Lyon, the English actor, is said to have duplicatedthis feat, using a large London paper and including the marketquotations, reports of the debates in Parliament, the railroad17

Memorytime‑tables and the advertisements. A London waiter is said tohave performed a similar feat, on a wager, he memorizing andcorrectly repeating the contents of an eight‑page paper. Oneof the most remarkable instances of extraordinary memoryknown to history is that of the child Christian Meinecken.When less than four years of age he could repeat the entireBible; two hundred hymns; five thousand Latin words; andmuch ecclesiastical history, theory, dogmas, arguments; and anencyclopædic quantity of theological literature. He is said tohave practically retained every word that was read to him. Hiscase was abnormal, and he died at an early age.John Stuart Mill is said to have acquired a fair knowledge ofGreek, at the age of three years, and to have memorized Hume,Gibbon, and other historians, at the age of eight. Shortly afterhe mastered and memorized Herodotus, Xenophon, some ofSocrates, and six of Plato’s “Dialogues.” Richard Porson is said tohave memorized the entire text of Homer, Horace, Cicero, Virgil,Livy, Shakespeare, Milton, and Gibbon. He is said to have beenable to memorize any ordinary novel at one careful reading;and to have several times performed

for a purpose, could have no existence without memory, for memory is involved in every purpose. Not only the learning of the scholar, but the inspiration of the poet, the genius of the painter, the heroism of the warrior, all depend upon memory. Nay,