Transcription

ggio,“Doubting Thomas"1

OverviewOverview ofof ReneRene Descartes’Descartes’ ckground.Summary.Meditation I.Meditation II.Meditation III.Meditation IV.Meditation V.Meditation VI2

ReneRene DescartesDescartes(1596-1650):(1596-1650):When our own ideas are absolutelyclear & distinct, free from allcontradiction, then we are certainwe possess the truth.3

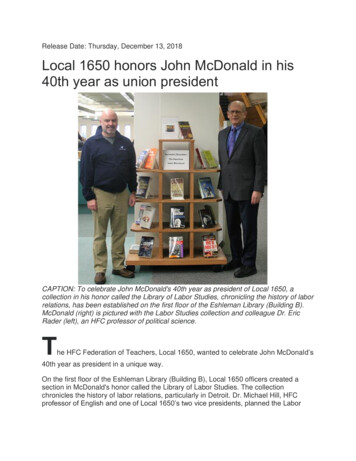

I.I.Background:Background:1596-1650, born at La Haye, a smalltown in Touraine, France.Educated at a Jesuit college of LaFleche. He was dissatisfied with thecourse of instruction because itchiefly consisted of the transmissionof the received opinions.1637 he published Discourse onMethod.1640 he grievously experienced thedeath of his 5 yr. old illegitimatedaughter Francine.4

I.I.Background:Background:Educated at a Jesuit college of LaFleche. He was dissatisfied with thecourse of instruction because it chieflyconsisted of the transmission ofreceived opinions.1619 in a series of dreams Descarteswas convinced that he was favored byGod, destined to be a philosopher.These dreams motivated him to inventa method of formal reasoning thatwould unite both mathematics and thephysical sciences.5

I.I. Background:Background:1641 he publishedMeditations on TheFirst Philosophy withsix sets of objectionsfrom variousdistinguished persons(including Hobbesand Gassendi),&Descartes’ Repliesto the Objections.6

I.I. Background:Background:1644 Descartes publishedPrinciples of Philosophy.1649 he became (with muchhesitation) an instructor to Queen“King” Christina of Sweden.1649 He published The Passionsof the Soul.Feb. 11th, 1650 he died ofpneumonia as a result of theSwedish climate and demandsmade upon him by the Queen.7

Outline:Outline:I.II.III.Search for Intellectual CertaintyDescartes’ Goal, Method, & PlanMethod:Example from mathematicsIntuition and DeductionRules of MethodIII.Methodic DoubtReversal doubtCogito and the selfV.VI.VII.VIII.The Existence of GodThe Existence of ThingsMind and BodyOther Models8

alCertainty:Certainty:1.Jesuit college of La Fleche. Descartes with problem of intellectual certainty.Attending one of the most celebrates school in Europe, yet he “found myselfembarrassed with many doubts and errors.”2.Ancient literature stimulated the mind but could not guide behavior.3.Though he honored theology and seemed to remain a pious Catholic to theend, he did not find in theology a method by which these truths could bearrived at solely through the power of reason.4.In philosophy, “no single things is to be found in it which is not subject ofdispute, and in consequence which is not dubious.”5.In practical life by means of traveling, “the great book of the world,” he metmen of diverse temperaments and conditions” and collected variousexperiences.” Among men of the world, he hoped to discover more exactmeaning in practical life. But, he found as much difference of opinion amongpractical people as among philosophers.9

alCertainty:Certainty:6.From his experience with the book of the world, Descartes decided “to believenothing too certainly of which I had only been convinced by example andcustom.”7.He resolved to continue his search for certainty and on 10 November 1619,had three dreams, which unmistakably convinced him that he must constructthe system of true knowledge upon the powers of human reason alone.8.Descartes broke with the past to give philosophy a fresh start. His system oftruth will be derived from his own rational powers; he will no longer rely onprevious philosophers for his ideas, nor accept any idea as truly only because itwas expressed by someone with authority. Aristotle’s reputation nor theauthority of the church could suffice to produce the kind of certainty hesought.10

II.II. Descartes’Descartes’ Goal:Goal:Lay the foundations for acquiring certain knowledge of theworld and to proceed to acquire that knowledge through acareful use of the method he prescribed.If we use reason carefully, following his method, then we willbe able to attain certain knowledge of the truth.All aspects of nature may be investigated the same way, andthat, ultimately, we may hope to achieve a unified11understanding of the world.

II.II. Descartes’Descartes’ Method:Method:Descartes placed a priority on epistemology and findinga method of acquiring knowledge.Skeptical of knowledge he had learned in his schooling.How can one distinguish true beliefs from false beliefs?How could the false beliefs Descartes acquired be discounted,and only true beliefs be accepted?Since Descartes was “especially pleased with mathematics,because of the certainty and self-evidence of its proofs,” andalso that he “ was astonished that nothing more noble hadbeen built on so firm and solid a foundation.”12

Method:Method: TheThe NeedNeed forfor thethe Meditations:Meditations:“Some years ago I was struck by the largenumber of falsehoods that I had accepted astrue in my childhood, and by the highlydoubtful nature of the whole edifice that I hadsubsequently based on them. I realized that itwas necessary, once in the course of my life, todemolish everything completely and start againright from the foundations if I wanted toestablish anything at all in the sciences thatwas stable and likely to last” (m. 18).13

TheThe Method:Method:Descartes continues,“Once the foundationsof a building areundermined, anythingbuilt on them collapsesof its own accord; so Iwill go straight for thebasic principles onwhich all my formerbeliefs rested” (m. 18).14

Descartes’Descartes’ Method:Method:Knowledge Requires Certainty:Since Descartes believed that real knowledge requires absolutecertainty, namely, the kind of certainty we observe inmathematics.To achieve certainty of that sort, we need two things: A solid foundation; A way of building from the foundation to other truths.15

II.II. Descartes’Descartes’ Plan:Plan:Descartes was determined to discover the basis of intellectualcertainty in his own reason. He was well aware of his unique placein the history of philosophy:“although all the truths which I class among my principles have beenknown from all time and by all men, there has been no one up to thepresent, who, so far as I know, has adopted them as principles ofphilosophy as the sources from which they may be derived aknowledge of all things else which are in the world. This is why ithere remains to me to prove that they are such.”16

II.II. Descartes’Descartes’ Plan:Plan:His ideal was to arrive at a system of thought whose variousprinciples were true and were related to each other in such a clearway that the mind could move easily from one true principle toanother. But in order to achieve such an organically connected setof truths, Descartes felt that he must make these truths “conform toa rational scheme.” With such a scheme he could not only organizepresent knowledge but could “direct our reason in order to discoverthose truths of which are ignorant.” His first task therefore was towork out his “rational scheme,” his method.17

III.III. Descartes’Descartes’ MethodMethodA.It consists of harnessing the powers of the mind with a special set of rules.B.Insisted on the necessity of a method that is systematic and orderly.C.Minds naturally possess two powers: intuition and deduction, “mentalpowers by which we are able, entirely without fear of illusion, to arrive atthe knowledge of things.” But by themselves these powers can lead usastray unless they are carefully regulated. Method consists, therefore, inthose rules by which our powers of intuition and deduction areguided in an orderly way.18

C.C. InductionInduction && Deduction:Deduction:Descartes states:“These two methodare the most certainroutes to knowledge,”adding that any otherapproach should be“rejected as suspectof error anddangerous.”Thewholeedifice ofknowledgeIs built uponthe foundation ofIntuition and deduction.Intuition: “an intellectual activity or vision ofsuch clarity that it leaves no doubt in the mind.”Deduction is “all necessary inference from factsthat are known with certainty.”Whereas fluctuating testimony of our senses &imperfect creations of our imaginations leave usconfused, intuition provides “the conceptionwhich an unclouded and attentive mind gives usso readily and distinctly that we are wholly freedfrom doubt about that which we understand.”Intuition gives us not only clear notions but alsosome truths about reality (e.g., I think, that Iexist; sphere has a single surface truths that arebasic, simple, & irreducible. It is by intuition thatwe grasp the connection between one truth &another.Deductions are similar to intuition because theyboth involve truth. By deduction we arrive at atruth by a process, a “continuous anduninterrupted action of the mind. By tyingdeduction so closely with intuition, which is asimple truth we grasp immediately andcompletely, deduction indicates the relation oftruths to each other. Reasoning from a fact (notfrom a syllogistic premise) is at stake. So,remote conclusions are furnished only be19deduction.

WhatWhat isis anan Intuition?Intuition?Consider Steve Daniel’s definition of Intuition:“Intuition: that which is clearly and distinctly perceived, as well as the act ofimmediately apprehending something that is clearly and distinctly perceived. Sincenothing apprehended by the senses is known clearly and distinctly, no sensation is anintuition; and anything known intuitively (e.g., thinking) cannot be resolved intoanything simpler. To the extent that any idea is apprehended clearly and distinctly, it isknown as the object solely of the mind, and in that sense can be said to be innate.Intuitions can thus be both the activity of the mind in apprehending something clearlyand distinctly (and might thus be called inner) and the objects apprehended in thatway.” Dr. D.20

D.D.RulesRulesofofMethod:Method:Descartes’ method does not consistonly of intuition and deduction, butalso in the rules he formulated for theirguidance.Chief point of rules is to provide a clearand orderly procedure for the operationof the mind.It was his conviction that “methodconsists entirely in the order anddisposition of the objects toward whichour mental vision must be directed ifwe would find out any truth.”Rule III: When we propose to investigate asubject, “our inquiries should be directed, notto what others have thought, not to what weourselves conjecture, but to what we canclearly and perspicuously behold with certaintydeduce.”Rule IV: This is a rule requiring that other rulesbe adhered to strictly, for “if a man observethem accurately, he shall never assume what isfalse as true, and will never spend his mentalefforts to no purpose.”The mind must begin with a simple andabsolutely clear truth and must movestep by step without losing clarity andcertainty along the way.Rule V: We shall comply with the methodexactly if we “reduce involved and obscurepropositions step by step to those that aresimpler, and then starting with the intuitiveapprehension of all those that are absolutelysimple, attempt to ascend to the knowledge ofall others by precisely similar steps.”He offers 21 rules in Rules for theDirection of the Mind (rule, 3, 4, 5, and 8are most important and four precepts inDiscourse on Method which hebelieved to be perfectly sufficient.Rule VIII: “If in the matters to be examined wecome to a step in the series of which ourunderstanding is not sufficiently well able tohave an intuitive cognition, we must stop shortthere.”21

courseononMethod:Method:These four precepts are perfectly sufficient, “provided I took the firm andunwavering resolution never in a single instance to fail in observingthem.”1st: Only accept indubitable truth:“The first was never to accept anything for true which I did not clearly know to be such; tocomprise nothing more in my judgment than what was presented to my mind so clearly anddistinctly as to exclude all ground of doubt.”2nd: Break down every difficulty into many parts as possible to find adequatesolution:To divide each of the difficulties under examination into as many parts as possible, and asmight be necessary for its adequate solution.3rd: Inductive method: Simple to the complex:To conduct my thoughts in such order that by commencing with objects the simplest andeasiest to know, I might ascend by little and little, and as it were, step by step, to theknowledge of the more complex 4th: Completely thorough:“In every case to make enumerations so complete, and reviews so general, that I might be22assured that nothing was omitted.

gLookingforformethodmethodlikelikeMathMathD. Example of Mathematics: Best example of clear andprecise thinking.1. “My method,” he writes, “contains everythingwhich gives certainty to the rules of arithmetic.”2. Descartes wanted to make all of knowledge a“universal mathematics.”23

gLookingforformethodmethodlikelikeMathMath3. Mathematical certainty is the result of a special way of thinking,and if he could discover this way, he would have a method fordiscovering true knowledge, “of whatever lay within thecompass of my powers.”4. Mathematics is not itself the method but merely exhibits themethod. Specifically, he discovered that the mind is able toapprehend directly and clearly certain basic truths, that we arecapable of knowing some ideas with absolute clarity anddistinctness.5. Mathematical reasoning showed him that we are able todiscover what we do not know by progressing in an orderly wayfrom what do know.Descartes as convinced that his method contained “primary24rudiments of human reason” and that with it he could elicit “truthsinevery field whatsoever.”

ceexperience&&experimentexperimentCompared with Bacon & Hobbes, Descartes puts very littleemphasis in his method upon sense experience & experiment inachieving knowledge. How is that we know the essentialqualities? For ex. Descartes asks: “At one time a piece of wax ishard, has a certain shape, color, size, and fragrance. But when webring it close to the fire its fragrance vanishes, its shape & colorare lost, and its size increases. What remains in the wax thatpermits us still to know it is wax?” “It cannot, “ says Descartes,“be anything that I observed by means of the senses, sinceeverything in the field of taste, smell, sight, touch, & hearing ischanged, & still the same wax nevertheless remains.” It is“nothing but my understanding alone which does conceiveit solely an inspection of the mind,’ which enables me to knowthe true qualities of the wax. “What I have said about the wax canbe applied to all other things external to me.”He relies for the most part upon the truths contained in the mind,“deriving them from [no] other source than certain germs of truth25which exist naturally in our souls.”

III.III. MethodicMethodic Doubt:Doubt:Descartes used method of doubt in order have an absolutelycertain starting point for building up our knowledge.Since our rules say we should never accept anything about which wecan entertain any doubt, Descartes now tries to doubt everything, sayingthat “because I wished to give myself entirely to the search after truth, Ithought it was necessary for me to reject as absolutely falseeverything concerning which I could imagine the least ground of doubt.” Sweep away all former opinions, “so that they might later on be replaced, either byothers which were better, or by the same, when I had made them conform to theuniformity of a rational scheme.”26

FirstFirst Meditation:Meditation: ArgumentsArguments forforDoubtingDoubting allall HisHis beliefsbeliefs1.He first observes that the senses sometimes deceive, forexample, objects at a distance appear to be quite small, andsurely it is not prudent to trust someone (or something) thathas deceived us even once. However, although this may applyto sensations derived under certain circumstances, doesn’t itseem certain that “I am here, sitting by the fire, wearing awinter dressing gown, holding this piece of paper in my hands,and so on”? (AT VII 18: CSM II 13).27

FirstFirst Meditation:Meditation: ArgumentsArguments forforDoubtingDoubting allall HisHis beliefsbeliefsDescartes’ point is that even though the senses deceive us some ofthe time, what basis for doubt exists for the immediate belief that, forexample, you are reading this article? But maybe the belief of readingthis article or of sitting by the fireplace is not based on truesensations at all but on the false sensations found in dreams. If suchsensations are just dreams, then it is not really the case that you arereading this article but in fact you are in bed asleep. Since there is noprincipled way of distinguishing waking life from dreams, any beliefbased on sensation has been shown to be doubtful. This includes notonly the mundane beliefs about reading articles or sitting by the firebut even the beliefs of experimental science are doubtful, becausethe observations upon which they are based may not be true butmere dream images. Therefore, all beliefs based on sensation havebeen called into doubt, because it might all be a dream.28

GroundsGrounds ofof Doubt:Doubt: FirstFirst Meditation:Meditation:“I should abstain from the belief in things whichare not entirely certain and indubitable no lesscarefully than from the belief in those whichappear to me to be manifestly false.”29

II.II. TheThe GoalGoal ofof Meditations:Meditations:Establish something that is lasting in science(which means human knowledge).He is interested in foundations of knowledge.30

III.III. Method:Method:Method: It is a radical approach.Look at all our beliefs.Any belief I can doubt, I’m going to consider it false.What can’t be doubted is true. Therefore, anythingleft is “certain.Not only is it a radical approach in destroying “true”beliefs but also a strong approach in building beliefs.31

verI have up till now accepted as most true Ihave acquired either from the senses or through thesenses. But from time to time I have found that thesenses deceive, and it is prudent never to trustcompletely those who have deceived us even once”(VII.18). Descartes.32

statementsbybyReneReneDescartes:Descartes:“So serious are the doubts into which I have beenthrown as a result of yesterday’s meditation that Ican neither put them out of my mind nor see any wayof resolving them. It feels as if have fallenunexpectedly into a deep whirlpool which tumblesme around so that I can neither stand on the bottomnor swim up to the top. Nevertheless I willproceed until I recognize something certain, or, ifnothing else, until I at least recognize for certain thatthere is no certainty. Archimedes used to demandjust one firm and immovable point in order to shiftthe entire earth; so I too can hope for great things if Imanage to find just one thing, however slight, that iscertain and unshakeable (VII:24).”33

III.III. Method:Method:Questions:1.If you are to doubt everything in order to knowsomething, does he ever doubt his own method?2.Does he even doubt basic mathematical,geometric truths or is he only concerned with“truths” we care about?3.Are there are certain high probable truths thatappear productive? Should we really throw themout?4.Should we doubt our most basic beliefs?34

FirstFirst Meditation:Meditation:WithholdingWithholding PolicyPolicy Method:Method:Assent to (Believe) opinions that arenot dubious and uncertainOpinions:SortWithhold Assent from (Doubt) dubious,uncertain opinions35

HeHe alsoalso goesgoes oneone stepstep further further by considering false any belief that falls prey to even the slightest doubt. Thus, by the endof the First Meditation, Descartes finds himself in a whirlpool of false beliefs.Notwithstanding, the doubts and the supposed falsehood of all his beliefs are for the sakeof his method for:He does not believe he is dreaming;Not being deceived by an evil demon;His doubt is merely hyperbolic or methodological for his plan is to clear the mind ofpreconceived opinions that might obscure the truth.The goal then is to find something that cannot be doubted even though an evil demon isdeceiving him and even though he is dreaming. This first indubitable truth will then serveas an intuitively grasped metaphysical “axiom” from which absolutely certain knowledge36can be deduced.

V.V. TheThe OrderOrder ofof SystematicSystematic Attack:Attack:Class 1:SensesNon-sensory.Class 2:The Dreamer Argument:How do I know that I’m not just dreaming?The fact that we dream gives us reason to doubt that the external world exist at all.Does the dreamer argument undermine the existence of the eternal world at all?Class 3: The Demon Argument.Does the demon argument cast doubt on tautologies, basicmathematics, physics, medicine, fundamental convictions ofknowledge).The demon could be tricking us (even 2 3 5).37

OutlineOutline ofof Meditations:Meditations:Meditation 1:Meditation 2:Meditation 3:Meditation 4:Meditation 5:Meditation 6:Methodic DoubtCogitoGodTrue and FalseEssence Corporeal Reality andexistence of GodExistence of Corporeal Realityand Mind/Body Relation38

ObjectorsObjectors (2,(2, 3,3, andand 44 areare thethe mostmost philosophical;philosophical;1,1, 5,5, 6,6, && 77 areare mostlymostly theological).theological).Father Mersenne circulates Descartes to the followingfor replies:Arnauld (4th Set of Objections)Jean Pierre Bourdin (7th Set of Objections)Caterus (1st Set of Objections)Pierre Gassendi (5th Set of ObjectionsHobbes (3rd Set of Objections)Father Mersenne (largely compiled by Mersenne; 2ndSet of Objections).39

odicDoubt:Doubt:A. Three Areas of Doubt: Sensory Experience, DreamArgument; and Malevolent Demon (seemingly certain):B. Recognize my own imperfection, thus my deceptionregarding what is “seemingly certain”C. Resolution to withhold assent to what is (possibly) false40

1.1. DoubtingDoubting SenseSense Perception:Perception:Sometimes our senses can deceive us. For example,objects sometimes look different from a distance thanthey do close up. But generally, we take our senses tobe reliable indicators of what the world around us islike.However, since our beliefs based on sense perceptioncan deceive us, we have reason to “doubt.” If there isan alternative explanation, then we have grounds for41doubt.

statementsbybyReneReneDescartes:Descartes:Whatever I have up till now accepted as mosttrue I have acquired either from the senses orthrough the senses. But from time to time Ihave found that the senses deceive, and it isprudent never to trust completely those whohave deceived us even once” (VII.18). Descartes.“42

2.2. Dreaming:Dreaming:Another ground of doubt for our beliefs about the world is that wecould be dreaming for sometimes when we are asleep, we thinkwe are awake.You think you are awake right now? But can you prove thatyou are?How do you know that this is not just one of occasions whenyou really are asleep, but think you are awake?There are not “conclusive indications” by which sleep andwakefulness can be distinguished. So, you have an alternative43explanation, a ground of doubt, for the experience you are having.

MethodicMethodicDoubt:Doubt: bvioustotous:us:How do I know if I’m dreaming/awake?What can be clearer than “I’m walking my collie downthe street.” But when I am asleep, I dream the samething. Thus, there is no “Conclusive indications bywhich waking life can be distinguished from sleep.”44

2.2. Dreaming:Dreaming:No inspection of the contents of your experienced willhelp you decide if you are awake or asleep. Thus, youmust set aside your belief, for example, that there is aprofessor in front of you. Likewise, you must set asideall beliefs based on sense experience until you can becertain that they are true.These include not only beliefs about the particularobjects around you, but also more general beliefs aboutthe world, including scientific beliefs, as well as the verygeneral belief that there is a world at all.45

3.3. DoubtingDoubting aa PrioriPriori Beliefs:Beliefs:The kind of beliefs we have wondered above are sometimes called a posteriorithat is, acquired ‘posterior to’ or after you begin to have, experience. Still, wehave many beliefs that we believe independently of our experience. Thesebeliefs are called a priori-that is, knowable, ‘prior to’ experience. Thus, theirtruth can be determined independently of experience.Consider 1 1 2. You can tell whether that is true without conducting anexperiment. Simply by having an understanding of addition and the concept of1, you can see that, indeed, one plus one equals 2.Consider a triangle has three sides. Simply by knowing the definition oftriangle, you can tell that proposition to be true.Descartes believes we have a priori beliefs but he thinks they come from innateideas.46

4.4. TheThe EvilEvil Deceiver:Deceiver:Can we be sure that such beliefs are true, that, for instance, 1 1 2? Is therean alternative explanation for why we believe this, other than it is true?There could be an extremely powerful deceiver who brings about that wheneveryou think 1 1 2, you are wrong. Can you be certain that there is no suchdeceiver?Another way of thinking about this is simply to suppose that your brain waswired up incorrectly, so that whenever you think of a false thought, such as 1 1 3, you have feeling of certainty that it is true, and whenever you think atrue thought, 1 1 2, you have a feeling of certainty that it is false.Now, how do you know that this is not the case? Could an evil deceiver havescrambled your brains, so that you are constantly confused? Can you be certainthat this has not happened to you?47

4.4. TheThe EvilEvil Deceiver:Deceiver:Descartes believes that he cannot be certain of even his seemingly most certainbeliefs such as the truths of mathematics, for he has found an alternativeexplanation of why he believes them, which he is unable to rule out.Descartes’ ground of doubt for a priori beliefs, namely, the evil deceive, issufficient to cast doubt on all his beliefs.Why did not he not just start off using the evil deceiver as a ground of doubt?The answer: Descartes suspects that, in fact, some of the beliefs he has set asideare true, while others are not.Even if there is not an evil deceiver-and he will show us that there is not, thereare still good reasons for doubting some of our beliefs, such as those based onsense perception. Thus, it is important to be aware of all of the reasons for48doubting each set of beliefrs.

4.4. EvilEvil Demon:Demon:Because of the evildemon, we can’t eventrust the laws of logicsuch as the law of noncontradiction.49

DownwardDownward SpiralSpiral ofof MethodicalMethodical Doubt:Doubt:Dreamargumentcast doubton collectivesense of realityDoubt ofsense perceptionscast doubton individualSense perceptionsEvil Demonargumentcast doubt on your thought process50

statementsbybyReneReneDescartes:Descartes:“So serious are the doubts into which I have beenthrown as a result of yesterday’s meditation that Ican neither put them out of my mind nor see any wayof resolving them. It feels as if have fallenunexpectedly into a deep whirlpool which tumblesme around so that I can neither stand on the bottomnor swim up to the top. Nevertheless I willproceed until I recognize something certain, or, ifnothing else, until I at least recognize for certain thatthere is no certainty. Archimedes used to demandjust one firm and immovable point in order to shiftthe entire earth; so I too can hope for great things if Imanage to find just one thing, however slight, that iscertain and unshakeable (VII:24).”51

o: gito ergo sum: discovery of a certain and unshakeable truthB.What am I?1.rational animal? No: uncertainty regarding meaning of"rational" & "animal“2.Am I a bodied soul? No: indistinct apprehension of mybodily existence3.I am (finite) substance: mind: principal attribute of mind:thinking; modes of thinking: doubting, understanding,affirming, denying, willing, refusing, imagining, sensing52

o: tuition of the piece of wax: what can be clearly and distinctlygrasped?1.Nothing by sensing the wax: a flux of changing impressions2.The wax remains singular, the appearances change fluidly3.Is this through the imagination? No, the wax "takes on an evengreater variety of dimensions than I could ever grasp with theimagination" (22)4.The wax remains singular in all the innumerablerepresentations5.Is the wax perceived by the mind alone? – apprehending theunchanging substance underlying variegated appearances isan inspection on the part of the mind alone"what I thought I had seen with my eyes, I actually grasped solely withthe faculty of judgment, which is in my mind" (22) 53

nd Meditation:22ndMeditation: AA CloserCloser LookLookDescartes is in a predicament when he begins 2nd Meditation for he seems unable tobe certain of any of his beliefs. Thus, he has put them aside.“I, suppose, then, that all things that I see are false; I persuade myself thatnothing has ever

II. Descartes’Plan:II. Descartes’Plan: Descartes was determined to discover the basis of intellectual certainty in his own reason. He was well aware of his unique pl ace in the history of philosophy: “although all the truths which I class among my principles have b een known from