Transcription

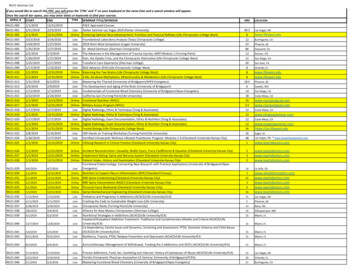

HOW DO YOU “DESIGN” ABUSINESS ECOSYSTEM?By Ulrich Pidun, Martin Reeves, and Maximilian SchüsslerThis article is the second in a series of publications offering practical guidance on businessecosystems. The first article addressed thequestion “Do you need a business ecosystem?”,this article deals with ecosystem design, andsubsequent articles will address how to manage a business ecosystem and how to measureits success over time.If designing a traditional business model islike planning and building a house, designing an ecosystem is more like developing awhole residential district: more complex,more players to coordinate, more layersof interaction and unintended emergentoutcomes.What makes ecosystem design distinctive isthat it requires a true system perspective. Itis not sufficient to design the value creation and delivery model; the design mustalso explicitly consider value distributionamong ecosystem members. This is furthercomplicated by the limited hierarchicalcontrol in an ecosystem and the need toconvince partners to participate, whichposes specific governance challenges. Andecosystems exhibit strategic challenges notfound in other governance models, such ashow to solve the chicken-or-egg problem ofcreating a critical mass of partners and customers during launch and how to build ascalable and defendable model.Moreover, business ecosystems, similar toresidential districts, cannot be entirelyplanned and designed—they also emerge.This adaptability is actually one of theirmajor strengths. However, there are somekey design choices you need to get right inorder to increase the odds of success. Thesedesign choices are not independent; theymust be consistent with one another andoffer a coherent overall configuration.Based on an analysis of more than 100 successful and failed ecosystems across sectorsand geographic markets, we find that theecosystem design challenge can be addressed by working through six sequentialquestions (see Exhibit 1): What is the problem that you want tosolve?

Exhibit 1 The Six-Step Journey of Business Ecosystem Design1What is the problem thatyou want to solve? Is the problem big enough? Is an ecosystem the right choice? What kind of ecosystem do you need?4How can you capturethe value of your ecosystem? What should you charge? Whom should you charge?23Who needs to be partof your ecosystem? What are the players and roles? Who should be the orchestrator? How can the orchestrator motivate theother players?5 How open should the ecosystem be? What should the orchestrator control?6How can you solve thechicken-or-egg problem? What does it take to achieve critical mass? What is the minimum viable ecosystem? Which side of the market should youfocus on?What should be the initialgovernance model of yourecosystem?How can you ensure theevolvability of your ecosystem? How can you scale the ecosystem? How can you defend the ecosystem? How can you expand the ecosystem? How can you protect against backlash?Source: BCG Henderson Institute. Who needs to be part of yourecosystem? What should be the initial governancemodel of your ecosystem? How can you capture the value of yourecosystem? How can you solve the chicken-or-eggproblem during launch? How can you ensure evolvabilityand the long-term viability of yourecosystem?Step 1: What is the ProblemThat You Want To Solve?Is the Problem Big Enough?Before you can start designing your ecosystem, you must make sure that the problemthat the ecosystem is supposed to solve isclearly defined and large enough to justifythe high upfront investment and to convince the right partners to participate. Thevalue proposition for a new ecosystem cancome from removing an existing friction(anything that dissuades customers frombuying a product or service, such as highcost, delay, poor quality, imperfect functionality, unpredictability, and misunderstanding or lack of trust) or from addressing an unmet or new customer need.The value potential from addressing an unmet need is difficult to predict but potentially very rewarding, because there is initially no offering to compete with. Whowould have guessed 20 years ago that posting selfies, photos of your food, and cat videos is such a deep human need that multibillion-dollar businesses like Instagram andYouTube could be built on them? By contrast, removing an existing friction is morepredictable. The ecosystem value proposition is a function of the size of the friction,the share of the friction that can be eliminated by the ecosystem solution, and thewillingness of customers to pay for it.Take, for example, Better Place, a startupfounded in 2007 to build an innovative ecosystem-based solution to power electric vehicles (EVs). Its breakthrough idea was toseparate car and battery. In this model, thedriver purchases a car without a battery,while Better Place owns the battery andcharges a mileage-based monthly fee forleasing, charging, and exchanging it. In thisway, Better Place could solve several fundamental problems of existing EV offerings:Because Better Place owned the battery,the EV could be offered at a competitiveprice, and the risk of obsolescence and lowresale value due to advances in batterytechnology was eliminated.Because Better Place built not onlycharging infrastructure but also switch sta-Boston Consulting Group BCG Henderson Institute 2

tions that could exchange batteries in amatter of minutes, the problem of limiteddriving range was also addressed. And finally, Better Place also solved the problemof electric grid capacity, because as the orchestrator of the EV ecosystem it could balance the power demand from cars withgrid capacity. Better Place was thus able toremove substantial frictions and offer anenormous benefit to the world. However,as we will see, the ecosystem failed because of other weaknesses in its design.The specific value proposition of a businessecosystem is context dependent. For example, frictions in traditional retail weremuch higher in China than in the US, because China had no significant retail orpayments infrastructure and it was difficultfor consumers to get access to many products they were looking for. This explains inlarge part the success of transaction ecosystems like Taobao and Tmall, which largelyremoved these frictions.In a similar vein, B2C ecosystems are typically easier to establish than B2B ecosystems, because many existing B2C relationssuffer from relatively high transactioncosts, while B2B offerings are more likelyto be characterized by mature companieswith optimized professional relationships.In the early 2000s, there was huge excitement about the value potential of B2Bmarketplaces in the US, with estimatedonline exchange potential of more than 5 trillion by 2005. In fact, by that year, almost all B2B marketplaces in the US haddisappeared. The bubble collapsed mainlybecause the problems that could be solvedthrough these marketplaces were just notimportant or big enough.Again, the situation was different in China,where the lack of infrastructure made itdifficult for a business to find partners, aproblem that Alibaba largely solved. However, we also believe that advances in sensor technology, cloud computing, and dataanalytics will make it possible to addressnew and bigger problems, and IoT-basedbusiness models will likely fuel the nextwave of B2B ecosystems in the comingdecade.Is an Ecosystem the Right Choice?The next question that must be answeredis whether an ecosystem is the best way torealize the business opportunity. Ecosystems compete with other governance models, such as vertically integrated organizations, hierarchical supply chains, andopen-market models. As we discussed inthe first article of this series (“Do You Needa Business Ecosystem?”), an ecosystem isthe preferred model in unpredictable buthighly malleable business environmentsand when high modularity of the offeringis combined with a high need for coordination among players.There are many examples of business opportunities that are not well suited for anecosystem model. Who wants to fly in anaircraft that was built by a loosely coordinated ecosystem of companies? In thiscase, the complexity and integrated natureof the design, and the need for utmost attention to safety, favor an integrated modelor a hierarchical supply chain. On the otherhand, many business opportunities do notrequire a business ecosystem because theycan be realized in an open-market model.For example, if Saeco launches a new automatic espresso machine, the required coffee beans, water, and power supply are generic complements that consumers canpurchase in the open market and thencombine on their own.Sometimes the best governance model isnot so obvious—or can change over time.Zappos started as a transaction ecosystem,matching consumers with shoe manufacturers, but found that it could offer a moreconsistent value proposition by taking fullcontrol of the buyers’ experience with atraditional hierarchical supply chain model.What Kind of Ecosystem Do YouNeed?Not all business ecosystems are createdequal. Some business opportunities arebest organized as a solution ecosystem,which creates and delivers a product or service by coordinating various contributors.Others are best set up as a transaction ecosystem, which matches or links participantsin a two-sided market through a (digital)Boston Consulting Group BCG Henderson Institute 3

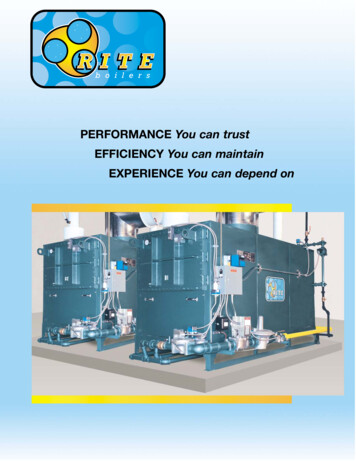

platform. And some are best organized as ahybrid, combining elements of a solutionand a transaction ecosystem. It is important to be clear about the type of ecosystem, because the types differ not only intheir structure but also in their purpose,success factors, and value creation mechanisms.Step 2: Who Needs to Be Part ofYour Ecosystem?What Are the Players and Roles?The initial design of a business ecosystemstarts with mapping the “value blueprint”:the activities that are required to deliverthe value proposition, the links amongthem, and the responsibilities of the various actors. The value blueprint also specifies the flow of information, goods or services, and money through the ecosystem.(See Exhibit 2.)The design of an ecosystem should be driven by its core value proposition. The initialvalue blueprint should incorporate theminimum number of domains (types ofparticipants or market sides) that are needed to provide this core value and expandover time. All examples of hybrid modelsthat we know started either as a transaction ecosystem (Airbnb, Alibaba, LinkedIn)or as a solution ecosystem (Apple iOS,Android) and added further domains andofferings only once they were firmlyestablished.The value blueprint is the basis for assigning roles to the various players. A solutionecosystem is typically characterized by acore firm that orchestrates the offerings ofseveral complementors, suppliers, and intermediaries (such as Better Place’s ecosystem in Exhibit 2). In transaction ecosystems, the orchestrator role is played by theowner of a central (mostly digital) platformthat links producers and their supplierswith consumers.The different roles have benefits and drawbacks. The orchestrator builds the ecosystem, encourages others to join, definesstandards and rules, and acts as arbiter incases of conflict. The broad scope of therole comes with the bulk of responsibilityfor ecosystem success and the sustainedlevel of investment that is required to getthe ecosystem going. The orchestrator isthe residual-claim holder of the ecosystem.While it has a big influence on the distribution of the value created, it must also makeExhibit 2 The Better Place Ecosystem’s Value BlueprintBattery manufacturerBatteryDesignPowerload balancingFlow of goods/servicesCarSoftware operatingsystemBetter PlaceUtilitiesCar manufacturerPowerBattery charging(rental fee)ConsumerBatterychargingBattery charging/exchange infrastructureFlow of informationSource: BCG Henderson Institute.Boston Consulting Group BCG Henderson Institute 4

sure that all relevant players earn a decentprofit. In return, the orchestrator can keepthe residual profit, which can be veryhigh (Apple iOS, Microsoft Windows) butalso negative for an extended period oftime (Uber, Lyft). Orchestrators that fail intheir responsibility to secure fair valuesharing will sooner or later destroy theirecosystems.Who Should Be the Orchestrator?In many business ecosystems, the assignment of the orchestrator role is clear. Forexample, in most transaction ecosystemsthe provider of the matching platform isthe natural orchestrator, and the roles ofproducers and consumers are readilyassigned. Similarly, some solution ecosystems are built on a technical platformthat serves as the basis for orchestration,such as the console of a video game ecosystem or the operating system on a PC orsmartphone.However, as a new ecosystem emerges, theorchestrator role may be contested. Thinkof the competing smart-farming ecosystemsthat are currently being built by equipmentmanufacturers ( John Deere), seed and cropprotection providers (Bayer-Monsanto), andtechnology players (Alphabet). And whoshould be the orchestrator of an effectiveecosystem for electronic health records:health insurers, providers, IT companies, orthe government?It is important to understand that you cannot unilaterally choose to be the orchestrator. You need to be accepted by the otherplayers in the ecosystem. In this regard,there are four requirements for a successfulorchestrator of a business ecosystem. First,the orchestrator needs to be considered anessential member of the ecosystem andcontrol resources needed for its viability,such as a strong brand, customer access, orkey skills. Second, the orchestrator shouldhave a central position in the ecosystemnetwork, with strong interdependencieswith many other players and a resultinghigh need and ability for effective coordination. Third, the orchestrator should beperceived as a fair (or even neutral) partner by the other members, not as a com-petitive threat. And finally, the best candidate is likely to be the player with thehighest net benefits from the ecosystemand thus a correspondingly high ability toshoulder the large upfront investments.Most companies seem to strive for the orchestrator role because they fear beingcommoditized, losing direct access to customers, or being exploited by another orchestrator. However, being a supplier orcomplementor in a business ecosystem canbe a very attractive role. Arguably, the biggest winners of the Californian gold rush inthe mid-19th century were the suppliers ofpots, pans, and Levi jeans. Similarly, suppliers and complementors can benefit fromlower investment requirements and the opportunity to join the most attractive of several ecosystems. Or they can hedge theirbets and participate in more than one ecosystem. In particular, if they provide important components that represent a bottleneck for the ecosystem, they can securea substantial share of the overall profits.1An example of a highly successful complementor is Adyen, a Dutch payments company enabling global platforms to supportall key payment methods around theworld. At the time of writing, the companyhad a market cap of more than 25 billion,had more than doubled its stock price sinceits IPO in June 2018, and reported revenuegrowth of 41% in the first half of 2019 at anEBITDA margin of 57%. Arithmetic dictatesthat only a small minority of firms can beorchestrators. We are convinced that manyincumbents would be well advised to puttheir strategic focus on finding attractivecomplementor or supplier roles.How Can the OrchestratorMotivate the Other Players?Ecosystem orchestrators face the additionalchallenge of motivating the required partners to commit and contribute to the ecosystem. Ron Adner identified two important risks for the feasibility of an emergingecosystem: co-innovation risk and adoptionrisk.2Co-innovation risk stems from the fact thatdeveloping a new or substantially im-Boston Consulting Group BCG Henderson Institute 5

proved value proposition is typically associated with high risks for the individual required innovations. In the case of abusiness ecosystem, these individual risksmultiply because of the interdependenceof the different components. The probability of technical success of an ecosystemsolution equals the mathematical productof the probability of success of all requiredcomponents, which can be very small ifjust one factor is small.This co-innovation risk is particularly relevant for solution ecosystems, where thefailure of one critical component is sufficient for the entire ecosystem to fail. Forexample, in early 2000, Nokia and Sony Ericsson started a race to bring to market thefirst 3G mobile phone capable of videostreaming. Nokia had forecast that by 2002more than 300 million mobile handsetswould be connected to the internet. Theactual number was 3 million; 300 millionwas reached in 2008, six years later. Nokiabecame a victim of co-innovation risk:While Nokia was fast to the market andcould sell its first 3G handset in 2002, before Ericsson, other actors in the ecosystemstill had to develop solutions to fully enable video streaming, such as formattingsoftware to fit TV images on small phones,router innovations allowing mobile phoneoperators to know which customer signedup for which plan, and digital rights management to ensure copyright protection forcontent owners. Before these innovationswere established, 3G video streaming couldnot be viable, rendering the device largelyuseless.Assessing co-innovation risk is important toevaluate the overall probability of successof the ecosystem, but also to identify thebottleneck components that need most attention and support. Intel understood thischallenge when the company designed itsecosystem and created the Intel Architecture Lab to drive architectural progresson the PC system and to stimulate andfacilitate innovation on complementaryproducts.Even if co-innovation risk seems limited,there is another challenge related to thevalue blueprint: adoption risk. Because ofthe high interdependencies in a businessecosystem, all contributors to the overallsolution need to be ready, willing, and ableto participate and invest in the ecosystem.A single instance of rejection is enough tobreak the entire adoption chain. For example, Better Place finally failed in spite of acompelling value proposition because itcould not secure the participation of oneimportant group of partners in its ecosystem, the car manufacturers. It got Renaulton board by guaranteeing volume andplacing an order of 100,000 cars, four yearsbefore it had a single customer. But Renault ultimately was Better Place’s only carmanufacturing partner.How can you evaluate critical partners’ incentives to participate? Partners are morelikely to commit if they score high on thefollowing criteria: High relative profit increase fromparticipation High competitive risk from non-participation Limited investments required forparticipation Limited risk from participation Existing capabilities to build onIf some critical players show a high adoption risk, you may need to reflect this inyour ecosystem design with incentives forparticipation. Incentives need not be onlymonetary; they can, for instance, also include access to customers or data. Ron Adner mentions digital cinema projectors asan example. The value proposition for replacing analog films and projectors by digital counterparts was generally compelling:higher resolution, better protection frompiracy, and significant savings in the valuechain. The cost of producing a conventional film was 2,000 to 3,000 per print, costing 7.5 million for a release shown on3,000 screens. Regardless of these advantages, adoption risk proved to be very highfor cinemas because the investment costsBoston Consulting Group BCG Henderson Institute 6

were prohibitive relative to the benefits.Despite efficiency gains, higher quality forconsumers, and more flexibility regardingthe offering, cinemas saw no need to adoptdigital projectors on a large scale. Onlyonce the film studios established a financing scheme in which they shouldered theinitial outlay for the projector, and studiosshared the benefits by paying a virtualprint fee per digital film screened (covering 80% of the cinema investment costs), werethe incentives for adoption high enough toestablish the new technology on a broaderscale.Step 3: What Should Be theInitial Governance Model ofYour Ecosystem?How Open Should theEcosystem Be?Ecosystem governance is an important design choice because it creates an indirectform of control appropriate to the complexity and dynamism of an ecosystem. It establishes the standards, rules, and processes that define an ecosystem’s formal orinformal constitution. Governance needs tobalance two requirements for ecosystemsuccess: value creation (rules of collaboration to co-create value as an ecosystem)and value sharing (rules and processes forsplitting the value among ecosystemplayers).The single biggest governance question foran emerging ecosystem is its degree ofopenness. Questions in three areas must beanswered: Access. Which individual partners willbe allowed to participate in the ecosystem? Which requirements do they haveto fulfill in order to get access to theplatform and its resources? Participation. To what extent areecosystem partners invited to shapethe ecosystem? What is the scope,detail, and strictness of the rulesgoverning this? Who decides how thevalue created is distributed amongpartners? Commitment. What level of ecosystem-specific investments and co-specialization is required? Is exclusivitydemanded or are partners allowed tomultihome in competing ecosystems?In practice, we can observe successful ecosystems with very different levels of openness, from rather restrictive (Nespresso) tomanaged (video games) to very open (Airbnb). For example, the Chinese companyHaier chooses a rather open approach toward access to its emerging “internet offood” ecosystem, which tries to integrateplayers from the appliance, food, healthcare, home furniture, logistics, and even entertainment industries to create a comprehensive customer solution from buying tocooking, eating, storing, and cleaning. AsZhang Ruimin, chairman of the Haiergroup, put it, “We want to build an energetic rainforest rather than a structuredwalled garden.”On the other hand, Sony experienced theperil of an open governance model whenintroducing its e-reader. Alarmed by piracyin the music industry, publishers were extremely concerned to protect their rightsaround books. Sony did not manage to establish a governance model to address thisconcern. Therefore, Amazon could conquerthe e-book market as a late entrant by establishing the Kindle as a very closed platform that loaded content only from Amazon and precluded users from transferringbooks to any other device or to a printer.In some sectors, ecosystems compete ontheir degree of openness. For example, Android broke the dominance of Apple iOS asa mobile operating system with an opengovernance model, while Facebook overcame the weaknesses of Myspace’s openmodel by being initially very selectiveabout who it allowed to join and establishing the double-opt-in “friending” feature.How can you find the right level of openness for your ecosystem? The decision mustoptimize the tradeoff between the advantages of a more open setup and of a moreclosed setup. Open ecosystems can benefitfrom faster growth, particularly duringBoston Consulting Group BCG Henderson Institute 7

launch. They enable greater diversity ofparticipants and variety of offerings andencourage decentralized innovation. Openecosystems tend to use the market to guidetheir development; partners join and leaveand adjust their offers as customer demandand technologies evolve.yourself and what do you want to encourage complementors to do? A starting pointmay be your own assets and capabilities.However, as Hannah and Eisenhardt observe, “Perhaps in complex strategic settings like ecosystems, strategy is more consequential than initial capabilities.”On the other hand, open ecosystems aredifficult to control and are thus best suitedfor products and services with limiteddownside and relatively low cost of failure.In case of high failure costs, and a corresponding need to limit the downside, aclosed ecosystem may be the better solution. It allows for a more deliberate designof the ecosystem and for closer control ofpartners and of the quality of the offering.Moreover, a more closed ecosystem helpsthe orchestrator capture value by, for example, charging for access.Good ecosystem strategy may be to identify and occupy potential innovation or capacity bottlenecks that can become an important source of value. Successfulorchestrators claim important system control points that allow them to capture theirfair share of value. For example, Nest decided to engage in alarm and monitoringitself because these are essential functionalities for controlling the home. Applepre-installs Apple Maps on the iPhone inan attempt to oust Google Maps. And Google uses its Google Play store to control theotherwise very open Android ecosystem.The right level of openness will depend onthe relative importance of the individualfactors, such as growth versus quality, decentralized versus coordinated innovation,and speed versus consistency of co-evolution. Competition with other existing oremerging ecosystems in the same sectorcan also play a role, because a new ecosystem needs to find a differentiated positioning, such as the degree of openness.We have seen many ecosystems start witha rather closed governance model in orderto establish high quality and open up later.For example, the Q&A platform Quorastarted as an invite-only ecosystem that targeted prominent technology entrepreneurs.By building this dense and exclusive network of experts, Quora was able to developan inventory of high-quality content thatthen made it easy to attract a broader audience when the platform later opened up.However, there are also examples of ecosystems that start as open to gain tractionand become more closed later, such as theknowledge ecosystems investigated by Järviand her colleagues.3What Should the OrchestratorControl?As an orchestrator, you face an additionaldesign question: What do you want to doThere are, of course, many other initialgovernance questions. For example, whendesigning a transaction ecosystem, the platform orchestrator must decide whether thematching of producers and consumersshould be done by algorithm (Uber) or byusers (Facebook); whether pricing shouldbe based on rules and algorithms (LendingClub) or on offer and negotiation (eBay);and whether curation should be done byplatform editors (Wikipedia), user feedback(Airbnb), or algorithms (Google Search).These decisions depend on the specificcontext and get at the heart of the ecosystem’s operating model, value creationmechanism, and differentiation.We will address the question of ecosystemgovernance in a future article in this series.Step 4: How Can You Capturethe Value of Your Ecosystem?What Should You Charge?When the basic setup of the business ecosystem is defined, the next big design stepis to find a way to translate the benefitsthat the ecosystem creates for its customersinto value for its participants. Monetizationis one of the biggest challenges of the eco-Boston Consulting Group BCG Henderson Institute 8

system orchestrator, which must balancethree competing objectives: maximizingthe size of the total pie; enabling all important domains (groups of participants) ofthe ecosystem to earn enough profit to ensure their ongoing participation; capturingits own fair share of the value.To achieve this, the orchestrator must design not only the value proposition for thecustomer but also the value-sharing model,by defining the value proposition for eachgroup of relevant stakeholders. At the sametime, the orchestrator must make sure toown critical control points, such as accessto the customer, products with many interfaces, or critical services.In solution ecosystems, value capture istypically rather straightforward becausethe solution that the ecosystem creates canbe sold as a product or service. The orchestrator can in addition capture value fromcomplementary products or servicesthrough access fees, licensing fees, revenueshares, or sales of value-added products orservices to complementors. For example,Apple takes 30% of revenues for all appssold through its App Store, and Nespressotakes a license fee from machine makerssuch as Krups, Breville, and De’Longhi.Transaction ecosystems offer many moreoptions for capturing value. The orchestrator can charge for access, for example, witha general access fee to the platform, an enhanced access fee for producers for bettertargeted messages or interactions with particularly valuable users, premium accessfees for consumers, or enhanced curationfees for users who are willing to pay forguaranteed quality. The orchestrator canalso charge for usage in the form of a transaction fee, either a fixed fee per transaction or a percentage of the transactionprice. In addition, the orchestrator cancharge for supplementary products or services (such as invoicing, payments, insurance), or it can monetize the ecosystem indirectly through advertising revenues.Whom Should You Charge?The second critical question of value capture is whom to charge. Again, the orches-trator has a number of choices, such ascharging all participants, charging only oneside of the market while subsidizing theother side, or charging most users the fullprice while subsidizing selected marqueeusers or particularly price-sensitive users.Our analysis showed that mispricing onone side of the platform is a key reason forfailure, in particular in the launch phase(see the next section). For example, Table8,a platform for last-minute reservations insold-out restaurants, failed because itcharged the wrong side of the market. Thecompany learned the hard way th

Take, for example, Better Place, a startup founded in 2007 to build an innovative eco-system-based solution to power electric ve-hicles (EVs). Its breakthrough idea was to separate car and battery. In this model, the driver purchases a car without a battery, while Better Place own