Transcription

Nursing PracticeReviewCardiologyKeywords: Acute coronary syndrome/Myocardial infarction/Unstable anginaThis article has beendouble-blind peer reviewedIn this article. P athophysiology and risk factors for acute coronary syndrome Signs, symptoms, diagnosis and treatment of ACS Priorities in nursing care for patients with ACSDiagnosis, management and nursingcare in acute coronary syndromeKey pointsAuthors Selina Jarvis is research nurse and former Mary Seacole development scholar,King’s College Hospital Foundation Trust; Selva Saman is consultant, Port ShepstoneRegional Hospital, Port Shepstone, South Africa.1Acute coronarysyndrome isa commonand potentiallylife-threateningcondition associatedwith coronaryheart diseasePrimarypercutaneouscoronary interventionwithin 12 hours ofsymptom onset is thefirst-line treatmentPharmacologicalmanagement inthe acute phasefocuses on painrelief and preventionof further clotformation whileminimising the riskof bleedingAfter dischargefrom hospital,patients needsecondaryprevention involvingmedications, cardiacrehabilitation andlifestyle changesNurses play acrucial role indelivering care andpsychologicalsupport at allstages of thepatient journeyAbstract Acute coronary syndrome refers to a range of potentially life-threateningconditions that affect the coronary artery blood supply to the heart, and is a commonpresentation in patients with coronary heart disease. Understanding the diagnosticapproaches, as well as pharmacological and coronary interventions is crucial, giventhe prevalence of ACS. This article discusses current evidence-based guidance in themanagement of ACS and the critical role of nurses.2345Citation Jarvis S, Saman S (2017) Diagnosis, management and nursing care in acutecoronary syndrome. Nursing Times; 113: 3, 31-35.Every three minutes one person isadmitted to a UK hospital withacute coronary syndrome (BritishHeart Foundation, 2017), acommon and life-threatening conditionassociated with coronary heart disease. ACS(Box 1) refers to a range of conditionsaffecting the blood supply to the heart muscles (myocardium); these include unstableangina, non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction (NSTEMI) and ST segmentelevation myocardial infarction (STEMI).ACS can result from a sudden drop inblood flow through the coronary arteriessupplying the different regions of the myocardium. This can compromise the myocardium, leading to reversible ischaemia ora complete loss of blood supply, which inturn leads to myocardial infarction andultimately myocardial cell death (necrosis).In-hospital mortality from ACS hasfallen from 20% to around 5% over the past30 years, which may be due to better drugtherapies, prompt recognition and treatment protocols (National Institute forHealth and Care Excellence, 2013a). Timelymanagement is crucial to reduce the riskof mortality and further cardiac events.Nursing Times March 2017 / Vol 113 Issue 3 31Treatment aims to ease symptoms,improve coronary artery blood flow andprevent complications. Immediate management, combined with cardiac rehabilitation and secondary prevention, canimprove patients’ outcomes and quality oflife. Nurses have a key role in:l F acilitating and administering prompttreatment to patients;l P romoting the swift recognition ofdeterioration;l P roviding holistic care andpsychosocial support;l E ncouraging patients to engage inhealthy secondary-preventionbehaviours.PathophysiologyMost ACS cases are caused by atherosclerosis, which takes place in the coronaryarteries, often decades before a cardiacevent. The formation of an atheroscleroticplaque begins with low-grade inflammation in the inner layer of blood vessels. Theendothelial cells lining blood vessels sustain injury, change shape and becomeincreasingly permeable to fluid, lipids andwhite blood cells. Circulating cholesterolwww.nursingtimes.net

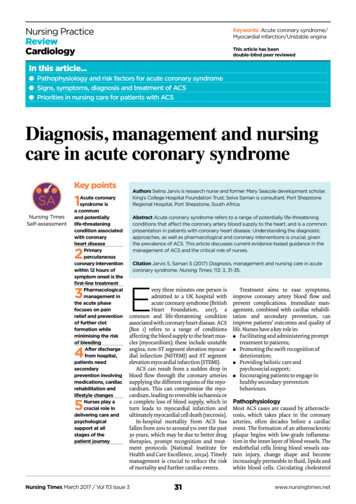

Nursing PracticeReviewcarriers, especially low-density lipoprotein (LDL), can enter the arterial wall andundergo oxidation. White blood cells areinvolved and transform into macrophages,which engulf LDL; when they become lipidladen they are referred to as foam cells.These lipid-rich plaques contain inflammatory cells, cellular debris, smoothmuscle cells with cholesterol, and a fibrouscapsule. Over time they can progress andcause luminal narrowing of the bloodvessel, thereby limiting blood flow.ACS is usually triggered by the rupture ofan atherosclerotic plaque in the wall of a coronary artery; this causes activation, adhesion and aggregation of platelets and theclotting systems, leading to the formationof a thrombus. If the thrombus completelyoccludes the coronary artery, the section ofthe myocardium supplied by that artery isstarved of oxygen, leading to myocardial cellnecrosis, and typical ST elevation changesare seen on an electrocardiogram (Fig 1). Inaddition, cardiac enzymes are released fromdamaged myocardial cells (troponin I and T,creatinine kinase MB isoenzyme), which canbe measured in the blood.Box 1. Universal definition of ACSA rise in blood troponin level above the 99th percentile of the normal range and/or afall in troponin alongside one or more of the following criteria:l Symptoms suggestive of cardiac ischaemial New electrocardiogram changes indicating new ischaemia (change to the STsegment or T wave or new left bundle branch block)l Development of a pathological Q wave in the ECGl Imaging evidence of new loss of viable myocardium or new regional wall motionabnormality (abnormal movement of heart muscle)Sources: Adapted from NICE (2014) and Thygesen et al (2012)Fig 1. STEMI changes in ACSBlockedblood flowAtheromaAtheroma liningcoronary arteryRisk factors for ACSACS is more common in men, older peopleand those with a family history ofischaemic heart disease. Modifiable riskfactors include smoking, obesity, hypertension, dyslipidaemia and poor diet. Lifestyle changes such as smoking cessation,weight loss, exercise, adherence to bloodpressure drugs, tight glucose control inpatients with diabetes, and management ofdyslipidaemias can be useful in both primary and secondary prevention.peter lambSigns and symptomsPatients typically present with centralchest pain or tightness described as dull orcrushing; it can radiate to the jaw or downthe left arm and normally lasts for 15 minutes. Some patients, however, such asthose with diabetes, older people orwomen, may not have chest pain.Mnemonics, such as SOCRATES, can beused to assess patients’ chest pain:l S – site of pain;l O – onset of pain;l C – character of the pain;l R – any radiation;l A – associated factors;l T – timing of the pain;l E – exacerbating/alleviating factors; forexample, position or inspiration;l S – severity of the pain using a ratingscale of 1-10 (10 being the worst pain).Shortness of breath, palpitations,IschaemiaInfarctionACS acute coronary syndrome. STEMI STsegment elevation myocardial infarctionsyncope or autonomic symptoms such assweating, nausea, tachycardia or vomitingmay also occur (with or without chestpain). Close attention to vital signs is critical as patients can deteriorate and becomehaemodynamically unstable or developheart failure and arrhythmias.Diagnosis and first investigationsA thorough clinical history and physicalexamination should be undertaken andsupported by an ECG. This helps delineatethe treatment pathway and, in cases ofSTEMI, decide whether the patient needsurgent reperfusion. If ACS is suspected,the emergency services should be calledand, on arrival, paramedics should perform an immediate ECG. Many paramedicsare trained to recognise ECG changes seenin STEMI, which include ST elevation of 1mm height in two adjacent chest leads,ST elevation of 2mm in two adjacent limbleads, and new left bundle branch block.If STEMI is suspected, paramedics willaim to take patients directly to a ‘heart attackcentre’ that offers primary percutaneousNursing Times March 2017 / Vol 113 Issue 3 32coronary intervention (PCI). Often they willcommunicate with the cardiology teambefore arrival, which will facilitate urgentcoronary reperfusion strategies (coronaryangioplasty with/without stents placed inthe affected coronary artery) once thepatient has arrived in hospital.Primary PCI has become the first-linetreatment in patients with STEMI presenting within 12 hours of onset of symptoms, provided it can be given within120 minutes of the time in which thrombolysis could be given (NICE, 2013a). If primary PCI is not available or there is a delay,thrombolysis may be performed (usingdrugs such as alteplase and reteplase) afterdiscussion with the on-call cardiologist –if there are no major contraindications.If the ECG does not reveal an MI but cardiac ischaemia is suspected, patientsshould be admitted and have serial 12-leadECGs to assess any dynamic changes. Ifthere is myocardial damage, cardiacenzymes (typically troponins T and I) areraised, which can help confirm the diagnosis. NICE (2013b) advises that troponinbe included in the initial assessment onadmission and a second sample be taken10-12 hours after symptoms began.Increases or decreases of troponin aboveor below the normal limit on the repeat testcan confirm NSTEMI. A negative troponinand no ECG changes can support a decisionto discharge patients who may haveunstable angina. These patients shouldreceive follow-up in a rapid chest pain clinicor in cardiology; their risk of adverse cardiacevents is 0.2% (Weinstock et al, 2015).Fig 2 outlines the principles of ACS diagnosis and management.Risk predictionAdults with NSTEMI or unstable anginashould be assessed for their risk of futureadverse cardiovascular events using anestablished risk scoring system that predictssix-month mortality (NICE, 2013b). Thishelps to plan clinical management anddecide on the best place of care (for example,www.nursingtimes.net

Fig 2. Overview of ACS diagnosis and managementACS suspectedSymptom variation in women, olderpeople and people with diabetes12-lead ECGClinical assessmentNo ST elevation seen onECG veTroponin testNSTEMIMedicalmanagement: aimfor PCI within 72hours in patientswith a six-monthmortality rate 3%ST elevation or LBBBseen on ECGConfirm theseare new ECGchanges-veUnstable anginaSTEMIDischarge andarrange follow-upinvestigationsPrimary PCI orfibrinolysis if delayACS acute coronary syndrome. ECG electrocardiogram. LBBB left bundle branch block.NSTEMI non-ST segment elevation myocardial infarction. PCI percutaneous coronaryintervention. STEMI ST segment elevation myocardial infarction.coronary care or a medical assessment unit).Several tools are available to stratify mortality risk in ACS, including:l G lobal Registry of Acute CoronaryEvents score (GRACE; Bit.ly/GRACERiskScore) (Granger et al, 2003);l T hrombolysis in Myocardial Infarction(TIMI) score (Antman et al, 2000).Table 1 compares GRACE and TIMI forrisk scoring in ACS.Pharmacological managementPain reliefPatients presenting with chest pain mayneed sublingual or buccal glyceryl trinitrate (GTN) to relieve pain; those withintractable pain may need a GTN infusion(NICE, 2013a). GTN promotes venodilationand dilatation of the coronary arteries. Itcan be given to patients with ischaemicchest pain provided their systolic bloodpressure is 90mmHg. It is contraindicatedin patients with an inferior MI or suspectedright ventricular involvement, as it cancause haemodynamic deterioration.Some patients with nitrate-refractorypain receive opioids, such as intravenousmorphine, at small doses every few minutes until they are pain free.There is some evidence that giving supplemental oxygen to patients with uncomplicated MI can be harmful (Stub et al, 2015).Antiplatelet agentsPlatelets play a pivotal role in clot formationafter an atherosclerotic plaque ruptures, sodual antiplatelet therapy is crucial in ACSmanagement – both in NSTEMI and STEMI.Aspirin is linked to reduced mortalityin ACS, with sustained effects at 10 years(Baigent et al, 1998), so it is standard practice to give patients 300mg of non-entericcoated aspirin on presentation. Alongsideaspirin, the P2Y12 antagonist group ofOxygenPatients with acute chest pain and presumed ACS do not need oxygen unlessthey present with hypoxia or heart failure.Nursing Times March 2017 / Vol 113 Issue 3 antiplatelet drugs is used. This drug classincludes clopidogrel and the faster-actingprasugrel and ticagrelor. Antiplateletagents are associated with potentially lifethreatening bleeding. NICE recommendsusing ticagrelor, as risk of bleeding islower than with the others (NICE, 2013a).The European Society of Cardiology recommends ticagrelor with aspirin inpatients with moderate-risk NSTEMI(Roffi et al, 2015). Many patients will haveto continue dual antiplatelet treatment for12 months after an MI regardless of how itwas managed.Anticoagulation agentsAnticoagulation is used to prevent clot formation. Fondaparinux, an antithrombinagent, reduces ischaemic events andimproves long-term morbidity and mortality; 2.5mg should be given subcutaneously once daily (Fifth Organization toAssess Strategies in Acute Ischemic Syndromes Investigators et al, 2006). It is associated with a reduced risk of majorbleeding compared with other anticoagulants – bleeding risk being a concern withmost of them (NICE, 2013b).In patients with renal dysfunction(serum creatinine 256μmol/L), unfractionated heparin is used. The decision togive an anticoagulant, and which one,revolves around whether and when thepatient is due to have PCI, as well as theirbleeding risk and cardiovascular risk score.Glycoprotein IIb/IIIa inhibitors (GPIs)GPIIb/IIIa receptor activation is the laststep in platelet aggregation when a clot isforming, so GPIs can be effective but,again, are linked to bleeding. NICE (2013b)recommends a GPI (for example, eptifibatide or tirofiban) be considered in patients:Table 1. Risk scoring in ACS: GRACE versus TIMITIMIHistoryAge l HypertensionDiabetes l Smokingl Dyslipidaemia l Familyhistory l History ofischaemic heart diseaselGRACElAge

chest pain or tightness described as dull or crushing; it can radiate to the jaw or down the left arm and normally lasts for 15 min - utes. Some patients, however, such as those with diabetes, older people or women, may not have chest pain. Mnemonics, such as SOCRATES, can be used to assess patients’ chest pain: l S – site of pain;