Transcription

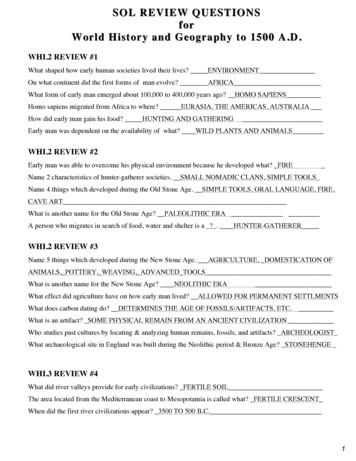

Chairman and General Fraser briefed onU.S. Army Military Surface Deployment andDistribution mission (USTRANSCOM /BobFehringer)Geography Matters inMaintaining Global MobilityBy William M. Fraser III and Marshall N. RamseyAll strategy is geostrategy: Geography is fundamental.—Colin S. Gray1General William M. Fraser III, USAF, isCommander of U.S. Transportation Command.Colonel Marshall N. Ramsey, USA, was ChiefStrategy Officer for the command.JFQ 73, 2nd Quarter 2014dvancements in transportationtechnology have seemingly collapsed the world’s vast distances.In this century we have witnessed thefirst commercially operated 500-kilo-Ameter-per-hour (km/h) magnetic levitation trains and the first privately ownedspace transport shuttle.2 In the futurewe may see a “hyperloop,” a partialvacuum tube that carries passengers inFraser and Ramsey81

USNS 1st Lt. Jack Lummus prepares to dock at causeway for vehicle unloading during maritime prepositioning force offload for exercise Cobra Gold(U.S. Marine Corps/Nathaniel Henry)capsules at speeds up to 1,220 km/h.3But such technological change does noteliminate geography as an importantfactor either in commercial or in military strategy and operations.4Geographic characteristics are oftenconstraining. Nations and significantplayers on the world stage compete inthe domains of land, sea, air, space, andcyber, and ungoverned areas in thesedomains invite bad actors.5 Weak andfailed states often lack critical transportation infrastructure that would help themovercome their geographic limitationsand support their populace during supertyphoons, floods, tsunamis, and othernatural or manmade disasters. Thesestates frequently lack good governance oftheir geographical area and have porousborders allowing groups to train, transit,or provide logistics to carry out transnational threats. Strong states may possess82Commentary / Geography Mattersthe critical transportation infrastructurerequired for humanitarian assistance/disaster relief operations. However, evenstrong states have waged war in the realmof geography and about geography.To meet its international securitycommitments and protect its nationalinterests, the U.S. military must remainrapidly mobile and expeditionary, supplying and resupplying itself once itis committed. U.S. TransportationCommand (USTRANSCOM) providesthe rapid positioning of expeditionaryforces. Even with distances collapsed bytechnology, geography matters for ourstrategy and operations. We have to spanthe globe and surmount geographicalconstraints to execute both peacetimeand wartime missions and be more responsive to those we support.Maintaining our global mobility capability in a fiscally constrainedenvironment has required the commandto engage in the most comprehensive andcollaborative strategic planning endeavorin its 26-year history. The result of our“journey of discovery” is a new strategicplan recommitting us to our ends, ways,and means. We at USTRANSCOMhave determined that the “ends” arerapidly projecting power and sustainingit, “ways” are achieving and maintainingglobal mobility, and “means” are assuredaccess and a well-developed and synchronized distribution network.EndsIn Joint Force of 2020, the Departmentof Defense (DOD) values global agility,with a premium placed on swift andadaptable military responses.6 In thiscontext, the United States will seek tomitigate conflict escalation or achievedeterrence by focusing on the decisiveJFQ 73, 2nd Quarter 2014

and quick employment of essentialand relevant forces. These forces maybe positioned forward, partnered withcapable allies, or based in the UnitedStates. In each case, strategic mobility isthe key element for power projection.USTRANSCOM has recognized thatthe ends—superior support to warfightersto project power and sustain operations—must not and will not change. Mostimportant, we recognized the need todevelop and implement bold and innovative ways to adapt to the future operatingenvironment. At the same time, werealized that our means—fiscal, materiel,and personnel—will experience increasedpressure for more efficiency for the foreseeable future. During development ofUSTRANSCOM’s strategic plan, we focused on developing processes, adaptingstructures, and reinforcing an enablingculture.The command will deliver the transportation and enabling capabilities thatmake America a global power by preserving our readiness capability, achievinginformation technology managementexcellence, aligning our resources andprocesses for mission success, and developing customer-focused professionals.The vision is to become the transportation and enabling capability provider ofchoice.7especially during surge operations.Through this optimal balance of TotalForce organic and commercial lift, wecan quickly pivot transportation resourceswherever and whenever needed.Improving strategic mobility will alsorequire decreasing lift and sustainmentrequirements and making intelligent useof prepositioned equipment in coordination with the Services and the DefenseLogistics Agency.9Acting in our role as the MobilityJoint Force Provider (see figure),USTRANSCOM advises and guidesmobility force sourcing solutions tobest effect for the supported geographiccombatant command.10 This enables usto quickly reallocate mobility capabilitieswhere they are needed while mobilizationof surge capacity of both organic andcommercial partners occurs. We can alsorapidly open aerial and seaports in or nearthe joint operational area.Maintaining global mobility is the wayto project power rapidly and sustain operations. It is also achieved and maintainedthrough freedom of action from assuredaccess to the global commons, a viableglobal distribution network, and the ability to rapidly transition from steady stateto contingency or crisis response operations. All of these capabilities mitigate thetime and distance constraints imposed bygeography on USTRANSCOM’s worldwide mission.MeansGlobal mobility for rapid power projection requires assured access to theglobal commons (relevant maritime, air,and space domains outside any country’s national jurisdiction), as well asaccess to a viable distribution networkand cyberspace. Assured access oftenrequires multiple paths to preclude asingle point of failure, which is true notonly for our physical networks but alsofor operations in the contested cyberdomain. The global commons are partof USTRANSCOM’s end-to-end distribution network, which includes portsof embarkation, en-route nodes, andports of debarkation. DOD relies onfriendly nations and allies for the use ofen-route and destination infrastructureto facilitate the global surface and aircorridors that comprise the distributionnetwork. Conversely, allies depend onU.S. mobility capabilities for combinedoperations. DOD must be free toWaysGlobal mobility supports the futurejoint force and globally integrated operations as described in Joint Force 2020by providing adequate transportationand distribution capabilities and capacities.8 In addition to readily deployablejoint forces and sufficient lift, theremust be a supporting global network.The foundation of DOD’s global mobility capacity is the organic capabilitiesprovided by USTRANSCOM’s Army,Navy, and Air Force component commands using Active-duty and Reservecomponent forces. However, integral tothe global mobility capacity needed bythe Nation are the additional capabilitiesgained through our commercial transportation providers. The assets and networksof our commercial partners are absolutelycritical in fulfilling global demands,JFQ 73, 2nd Quarter 2014Fraser and Ramsey83

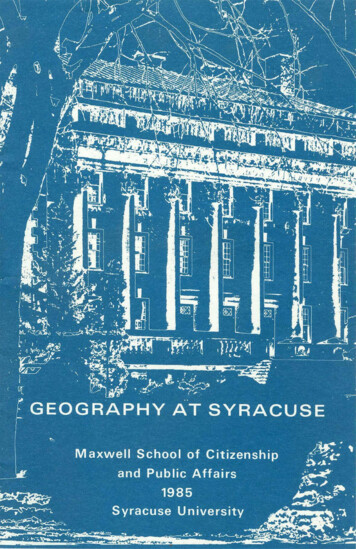

Sailor monitors flights in Joint Operational Support Airlift Center Execution Team area ofUSTRANSCOM Fusion Center (USTRANSCOM/Bob Fehringer)operate across the entire distributionnetwork with surety. This was true inthe past, is true today, and will be truein the future.World War II’s historic airlift operation over “the hump” of the Himalayaskept China in the fight against Japanand contributed significantly to the U.S.victory in the Pacific. In the ChinaBurma-India theater of operations,harsh weather, severe terrain, the enemy,and host nation sovereignty were allchallenges that airlift had to overcome,especially while waiting on constructionof the Burma road.11 Similarly, the HinduKush, the lack of seaports in land-lockedAfghanistan, the limited number of usefulroads and airfields, and other nations’sovereignties are challenges the commandmust overcome today when delivering,sustaining, and redeploying forces forOperation Enduring Freedom.Initially USTRANSCOM airliftedtroops, their combat equipment, andtheir sustainment materiel until groundlines of communication could be established. Assured freedom of action andglobal mobility allowed the commandto quickly deploy and employ mobility forces seamlessly. Our commercialpartners played a critical role by providing extended “reach” within theirbroader network of capabilities and trade84Commentary / Geography Mattersrelationships. This extended reach gavethe command flexibility and access it didnot otherwise possess.Access to the cyber domain is criticalfor global mobility. We execute logistics,transportation in particular, throughinformation systems operating largely onunclassified but protected networks andinclude participation of our commercialpartners and others through their information technology systems. Adversariesunderstand that transportation activitiescan signal operational intent, so ourinformation networks provide a lucrative target and a vulnerability we mustaddress. In addition our decisive andreliable command and control of strategic mobility operations is a capabilityour adversaries would like to acquire.Protecting, defending, and mitigatingadverse operations in cyber space is a keyfocus area for USTRANSCOM alongwith its component commands and commercial partners.The Global Distribution Network(GDN) is the foundation of our GlobalCampaign Plan for Distribution (GCPD). The health of the network is integralto strategic readiness and rapid projectionof power for many combatant commandsand their operational plans. Through itwe provide responsive and agile supportthrough DOD and commercial partners.As USTRANSCOM commander, myprimary objective for engaging leaderswithin and outside DOD is helping setthe conditions for the GCP-D. We aremeeting with key leaders in geographiccombatant command areas of responsibility to discuss existing diplomaticagreements, sustain partner-nation relationships, secure conditions for retrogradeoperations in Afghanistan, and exploreinfrastructure improvements that canserve our strategic requirements. At eachstop we engage with U.S. country teamsand host nation ministers of defense, foreign affairs, and transportation. Economicdevelopment is often discussed. Partnernations view being part of the GDN as asource of revenue for their countries, andthey frequently invest money and politicalcapital to further this objective.Many of our partner nations haveplans to develop transportation-relatedinfrastructure that will improve theircapabilities. These plans are frequently unsynchronized and focus on a single nodesuch as airfield construction, but withoutan associated road network. As the responsible agent for the GDN, the commandcollaborates with partners to coach themin the development of a comprehensive vision for their transportation networks. Aninfrastructure plan that is comprehensive,prioritized, and phased will achieve fargreater success, and this approach alignswell with our global transportation andcommercial network objectives.We will continue to foster thesepartnerships to maintain the readinessof the GDN and its ability to respond tofuture requirements. For example, theviability of the Northern DistributionNetwork (NDN) infrastructure—seaand aerial port facilities and road andrail networks—will remain vital afterthe conclusion of Enduring Freedom.Learning from NDN’s successful support of deployed forces when groundlines of communication through Pakistanwere interrupted, we are already partnering with U.S. Pacific Command(USPACOM) to lay the foundation fora Pacific Distribution Network as well aswith U.S. Africa Command. The PacificRim is one part of a complex networkof bilateral and multilateral relationshipsJFQ 73, 2nd Quarter 2014

that spans vast distances with minimalbasing. Intratheater movement in theUSPACOM area of responsibility issimilar to intertheater movement globallyand is often referred to as “the tyranny ofdistance.” We must be smart and efficientabout the way we use our scarce resourcesto achieve readiness for the PacificDistribution Network. As a baseline wewill nest our efforts within USPACOM’sstrategy to ensure we remain responsiveand ready to perform them. The Africancontinent has equally daunting distanceand access challenges.We also discuss aerial refueling interoperability during our engagements. Manyallied partners use the same platformswe do. We have developed standardizedprocedures, but there is a lack of synchronized certifications. We will continue tocontribute to the DOD effort to improveaerial refueling interoperability with ourpartners. More must be done in this areaand lessons learned must be turned intofuture solutions. In many cases, our partners’ preparedness to support coalitionoperations may hinge on this unique ability to fully employ their capabilities.But assured access to the global commons and a viable distribution networkare not enough. While it is clearly ourcomponents and commercial partnerswho successfully deliver the goods,USTRANSCOM develops optimalend-to-end distribution processes andsolutions across various transportationmodes and nodes. Our third means of rapidly projecting power is our unique abilityto synchronize plans, coordinate, andalign transportation operations aroundthe world, which is where our true valueadded is achieved. USTRANSCOM’s rolewill continue to be integral to overcominggeographical constraints.The command’s recently assignedGlobal Distribution Synchronizer role(see figure) ensures that geographic combatant commands’ transportation-relatedposture plans are synchronized andmutually supportive to achieve seamlessglobal mobility. We do this by participating in planning conferences and exercises.USTRANSCOM’s en-route infrastructure master plan is also synchronizedwith combatant commands to ensureJFQ 73, 2nd Quarter 2014capabilities exist at various ports, airfields,and multimodal sites when required.In particular, USTRANSCOM willassess the GDN vis-à-vis the strategicenvironment. The heart of the GCP-D isdeveloping all the requisite elements ofa “warm” network to operate anywhereon the globe, so when the time comeswe can quickly respond to it to meetthe Nation’s needs. Synchronizationof the efforts to set the conditions forfuture distribution operations is whereUSTRANSCOM, with the help of others, ensures that efforts are mutuallysupporting and achieve the desired objectives for strategic mobility.Lastly, in the past, USTRANSCOMoperated in the individual land, sea, andair segments of transportation. However,through our years of experience in ourDistribution Process Owner role (see figure), we realized we could move combatequipment via surface land/ocean and airroutes through multimodal hubs and notonly meet required delivery dates, butalso be more cost-effective. Multimodalis increasingly becoming our operationalnorm as is the ability to coordinate andsynchronize movements end-to-end.The ability to decisively engageglobally—literally overnight—hingeson the mobility and transportation assets USTRANSCOM coordinates andsynchronizes to rapidly project powerand sustain a global presence. Leadersat all levels of government tell me thatUSTRANSCOM makes mobility lookeasy, knowing full well it is not.Our command overcomes geographicconstraints and rapidly projects powerthrough global mobility, assured access, aviable GDN, and global synchronizationof distribution. The extraordinary abilityto rapidly project national power andinfluence—anywhere, anytime—is uniqueto the United States. Modern means oftransport alone cannot eliminate the strategic significance of terrain, environment,and vast distance.We must remember that the challengeof geography is compounded by the twintyrannies of time and cost. By nature, crisesdevelop quickly, and we are pressured torespond faster. Military personnel resourcesare expensive, and the cost of transportingthem and their sustainment increases withdistance.12 When effectiveness and responsiveness are not paramount, warfightersand customers need more cost-conscioustransportation solutions, preferably a rangeof costed options.All strategy must contend with geography even when it is not about contestedgeography.13 Together we are workingtoward a more effective and efficientcommand to provide America’s globalmobility and enable its capabilities wherever and whenever needed. Togetherwith our components, the DefenseLogistics Agency, and commercial partners, U.S. Transportation Commandwill continue to deliver the mobility andtransportation options that bolster ournation’s power. Together, we deliver. JFQNotes1Colin S. Gray, Fighting Talk: Forty Maxims on War, Peace, and Strategy (Westport, CT:Praeger Security International, 2007), 78.2See “Shanghai Maglev Train,” availableat http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/ShanghaiMaglev Train ; “Falcon 9,” available at www.spacex.com/falcon9 .3See “Hyperloop,” available at http://spacex.com/hyperloop .4Colin S. Gray, Modern Strategy (Oxford:Oxford University Press, 1999), 40.5Gray, Fighting Talk, 78, 80. Mankind doesnot live at sea or in cyberspace. Most wars entailwhere belligerents live, and therefore, landmatters most. Even though air and sea maydominate the conduct of a war, conflict’s likelyobjective is to influence the enemy’s behavioron the ground and often requires that the finalblow be delivered by ground forces.6Capstone Concept for Joint Operations:Joint Force 2020 (Washington, DC: The JointStaff, September 2012), available at O JF2020 FINAL.pdf , 4–7.7See “Our Story: 2013 to 2017,” availableat www.ustranscom.mil/strategy/v1.cfm .8Capstone Concept for Joint Operations, 12.9Ibid., 1.10Unified Command Plan 2011 (Washington, DC: The Joint Staff, April 6, 2011, withChange-1 dated September 12, 2011), 29–31.11William H. Tunner, Over the Hump:Berlin Airlift 50th Anniversary CommemorativeEdition (Washington, DC: Air Force Historyand Museums program, 1998).12Joseph S. Nye, Jr., The Future of Power(New York: PublicAffairs, 2011), 27.13Gray, Fighting Talk, 79.Fraser and Ramsey85

time and distance constraints imposed by geography on USTRANSCOM’s world-wide mission. Means Global mobility for rapid power pro-jection requires assured access to the global commons (relevant maritime, air, and space domains outside any coun-try’s national jurisdiction), as well a