Transcription

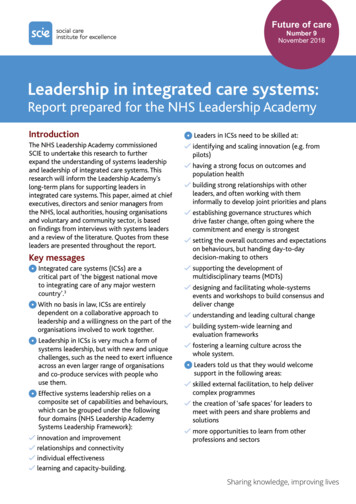

Future of careNumber 9November 2018Leadership in integrated care systems:Report prepared for the NHS Leadership AcademyIntroduction Leaders in ICSs need to be skilled at:The NHS Leadership Academy commissionedSCIE to undertake this research to furtherexpand the understanding of systems leadershipand leadership of integrated care systems. Thisresearch will inform the Leadership Academy’slong-term plans for supporting leaders inintegrated care systems. This paper, aimed at chiefexecutives, directors and senior managers fromthe NHS, local authorities, housing organisationsand voluntary and community sector, is basedon findings from interviews with systems leadersand a review of the literature. Quotes from theseleaders are presented throughout the report.i dentifying and scaling innovation (e.g. frompilots)Key messagesI ntegrated care systems (ICSs) are acritical part of ‘the biggest national moveto integrating care of any major westerncountry’.3 ith no basis in law, ICSs are entirelyWdependent on a collaborative approach toleadership and a willingness on the part of theorganisations involved to work together.L eadership in ICSs is very much a form ofsystems leadership, but with new and uniquechallenges, such as the need to exert influenceacross an even larger range of organisationsand co-produce services with people whouse them.E ffective systems leadership relies on acomposite set of capabilities and behaviours,which can be grouped under the followingfour domains (NHS Leadership AcademySystems Leadership Framework):i nnovation and improvementrelationships and connectivityindividual effectivenesslearning and capacity-building. aving a strong focus on outcomes andhpopulation health uilding strong relationships with otherbleaders, and often working with theminformally to develop joint priorities and planse stablishing governance structures whichdrive faster change, often going where thecommitment and energy is strongests etting the overall outcomes and expectationson behaviours, but handing day-to-daydecision-making to otherss upporting the development ofmultidisciplinary teams (MDTs) esigning and facilitating whole-systemsdevents and workshops to build consensus anddeliver change understanding and leading cultural change building system-wide learning andevaluation frameworks fostering a learning culture across thewhole system. Leaderstold us that they would welcomesupport in the following areas:s killed external facilitation, to help delivercomplex programmest he creation of ‘safe spaces’ for leaders tomeet with peers and share problems andsolutions ore opportunities to learn from othermprofessions and sectorsSharing knowledge, improving lives

s ystems leadership development for middlemanagers across the systemThe first 10 ICSs started in 2017, and four morewere announced in 2018. NHS England intendsthat other areas will become ICSs over time.Effective systems leadership will clearly be crucialto the success and impact of ICSs. Integratedsystems require distinctive leadership skills anda unique strategic perspective that may differsignificantly from traditional ways of leadinghealth and care organisations. masterclasses on: co-production theory and practice finance and risk-sharing scaling innovationunderstandinglocal government and social careThis paper looks at the components of effectivesystems leadership in the context of ICSsand STPs. Drawing on an evidence review andinterviews with ICS leaders, we explore howthey are working in a system-wide way acrossorganisational boundaries, and the leadershipskills and qualities they require. The paper alsolooks at the challenges and barriers to effectivesystems leadership in ICSs, and what enablespeople to overcome them. Finally, it sets out waysin which the support and development needs ofsystems leaders can be addressed. large-scale and large-group facilitation orking and influencing across multiplewlayers of governance.ContextOur health and care system is experiencingunprecedented pressures. The population is risingand ageing, and more people are living withcomplex and long-term conditions. Funding ishugely constrained and there are vacancies andskills gaps across the workforce. For decades,it has been widely agreed that breaking downorganisational barriers through better integrationhas the potential to deliver higher quality carethat achieves better outcomes and uses resourcesmore efficiently. Yet this goal remains elusive inpractice.The drive towards integrated care gained newform and impetus with the publication of theNHS ‘Five year forward view’ (2014),1 and ‘Nextsteps on the NHS five year forward view’ (2017).2These required NHS commissioners and providersto work together to develop sustainability andtransformation partnerships (STPs) to improveservices, taking a population-based approach totheir geographical ‘footprints’.Where such strategic partnerships andcollaboration are most advanced, STPs havenow developed further to create integrated caresystems (ICSs) – where NHS commissioners,providers and local councils work collaboratively,taking collective responsibility for resources andpopulation health. ICSs have no statutory basis,but depend on voluntary collaboration betweenNHS and local authority leaders to developa shared, system-wide approach to strategy,planning and commissioning, financial andperformance management, and driving integrationof care and services.2

Policy and operational contextICSs are an example of integration atorganisational, strategic and planning levels.They are intended to underpin, and result in,integrated care at service and patient levels.The governance and delivery structure can becomplex, and is not underpinned by a statutoryframework. Professor Chris Ham of The King’sFund described the approach as follows:The 2014 NHS ‘Five year forward view’1represented a major policy shift away from acompetition-based model of health care, towardscollaboration and integration. It recognised thatorganisations working together, sharing knowhow and resources, were more likely to meet thesignificant challenges of rising demand, limitedfunding and the need to improve outcomesand patient experience. Simon Stevens, ChiefExecutive of NHS England, recently called it ‘thebiggest national move to integrating care of anymajor western country’.3“It is important to recognise that ICSshave no basis in law and are entirelydependent on the willingness ofthe organisations involved to worktogether. NHS trusts and CCGs(clinical commissioning groups)have their own statutory duties andmembers of their boards may needreassurance that these duties arenot being compromised by ICSs.Different accountabilities in theNHS and local government mayalso cause tension.4”The first 10 ICSs vary considerably in geography,demography, population size, drivers for changeand number of partners involved. But they alsohave many characteristics in common:T hey are collaborative, involving NHScommissioners, providers, GPs and localauthorities.T hey are place-based.T hey adopt a population-based approach.T hey focus on outcomes.T hey focus on preventing ill health.T hey promote a shift towards more care inthe community and people’s homes, ratherthan hospital.T hey have a shared responsibility fordelivering strategy and outcomes.T hey share resources and financial risk(financial ‘system control totals’).T hey are given more autonomy from thecentre, including financial autonomy.3

ICSs are part of a larger drive towardscollaboration and integration that affects thewhole of the English NHS. At the very least,all NHS commissioners, providers and localauthorities in England are now expected tobe involved in STPs, which necessarily meansworking together and focusing on place andlocal population. Many are testing new modelsof care and some are developing integratedcare partnerships (ICPs) – these adopt a looserapproach to collaboration than ICSs, focusingon delivery without formalised collectiveresponsibility and shared risk.ICSs are set to become a permanent feature ofthe health and social care landscape. MichaelMacDonnell, National Director, TransformingHealth Systems at NHS England, recently madeit clear that collaboration and integration willremain central to the forthcoming 10-yearNHS plan:“The long-term plan for the NHS,which will be published in theautumn, will set out how we intendto catalyse [ICSs] across the country,supercharging their spread. Thesesystems are the opportunity andthe vehicle for providers to be at theforefront of evolving a health servicefit for the next 70 years.4”By their nature all these approaches areexperimental, but expectations are high. NHSEngland hopes that the early ICSs will generatelearning for the whole of the health and caresystem, while also producing meaningful benefitsin terms of outcomes, patient experience andefficiencies.4

Features of effective systems leadershipThe leadership model for health and care continues to shift from one that is hierarchical and focusedon a single organisation, to one that involves leading change across a whole range of organisationsusing influence rather than management direction.This shift is described in Figure 1.Figure 1 Leadership model for health and care1. Hierarchical2. Fixed, prescriptive3. Power-centred4. Focused on individual organisations5. Territorial, proprietary, centralised6. Professional-driven7. Transactional8. Primarily accountable to regulatorsand policy-makers9. Self-centred10. Short-term, task-focused11. Avoids conflicts12. Competitive, conflict-prone1. Horizontal, multidirectional2. Adaptive, comfortable with chaos3. Seeks to influence4. Place-based, whole system5. Complementary, diffused, distributed,participatory6. Person-centred, inclusive, co-productive7. Relationship-based, personal8. Primarily accountable to peopleand communities9. Altruistic10. Long-term, focused on transformation ofwhole system11. Surface conflicts, solution-focused12. Consensus seeking, builds a shared visionand narrativesLeadership in ICSs is very much a form ofsystems leadership, but those in leadership rolestold us they face a different and more complexset of challenges. It was described by one leaderas ‘turbocharged’ systems leadership. The role ofsystems leaders is emergent and evolving, andthe support they need is also likely to evolvefurther.Place-shaping – leaders told us that thereis an even stronger emphasis than beforeon focusing on people and place, andunderstanding how strategic plans relate tovery locally-based neighbourhood teams.Understanding how to commission anddeliver population improved health is anotherimportant skill.Leaders told us that they were expected tomanage the following new demands.L eading large-scale change – leadersin ICSs increasingly need to be skilled atleading complex, large-scale change, throughexcellent facilitation and influencing skills.S pan of influence – leaders in ICSs needto influence change across an even broadergroup of organisations and stakeholders,such as public health, housing, children’ssocial care, mental health and the voluntarycommunity sector.T ackling ‘wicked’ issues – systems leadershave always dealt with complex, multifacetedproblems, but some believe challenges arebecoming even more complex, evadingtraditional solutions. Examples of ‘wicked’issues include: regional estates strategies;cross-system workforce planning; shiftingcare out of hospitals and into communities;and planning for the winter.C o-creation and co-production – leaderstold us that to ensure that change on thisscale ‘sticks’, you need to co-design and coproduce solutions with those who receivehealth, care and support, and work effectivelywith elected politicians5

Innovation and improvementThe leaders of ICSs told us that they areincreasingly expected to understand how todevelop the right conditions locally to fosterinnovation. They are also expected to understandhow to scale innovation (e.g. from a pilot ornew model of care developed elsewhere, toother parts of the local system). This means thatleaders must encourage colleagues to test newapproaches and learn from innovations (e.g. inareas such as technology and self-care), and theymust be ready to offer additional support to staffif and when an innovation does not succeed.B uilding commitment within organisations– leaders need to focus on how they canbuild systems leadership skills deeper withinorganisations, engaging middle managers, andleaders of MDTs in their thinking.“There is an important role for us assenior leaders to build the vision andmake the strategic connections. But,increasingly, systems leadership willoperate within neighbourhood teams(MDTs).”“I am thinking more and moreabout how we support thrivingcommunities, building on people’sassets. Yes I have to track whetherwe are bringing down unnecessaryreferrals, but in the long run we needto be all focusing on these longerterm outcomes for communities.”(Local government leader, ICS)The findings of this study are structured aroundthe four domains of the NHS LeadershipAcademy’s Systems Leadership DevelopmentFramework:Innovation and improvementRelationships and connectivity(Senior clinician, ICS)I ndividual effectivenessLeaders in ICSs told us that they need to havea strong focus on outcomes. They must be ableto steer conversations and decisions away fromorganisational-specific objectives, towardsbroader outcomes for communities, such asreducing social isolation and promoting self-care.This is likely to mean that over time there will beless focus on traditional hospital-based metrics,and greater attention to the wider determinantsof health, such as people feeling sociallyconnected and able to support their own care.Learning and rningandcapacitybuildingAs well as workshops involving staff and thepublic, mechanisms for senior leaders fromacross the system to come together and havehonest face-to-face discussions are crucial.Leaders told us that using skilled externalfacilitators had been vital in enabling them tobuild trust, bring tensions to the surface anddiscuss difficult issues. In this context, NHSLeadership Academy interventions around wholegroup leadership development were welcome.InnovationandimprovementFigure 2 Systems Leadership DevelopmentFramework6

Relationships and connectivityLeaders of ICSs need to be able to buildproductive relationships. They told us that theyspend more time than ever before developinggood relationships with colleagues and, as part ofthis, trying to listen to and empathise with theirconcerns and issues. Often these relationshipsare fostered outside formal meetings, with lotsof ‘pre-work’ on the phone or over coffee toprepare for more formal partnership meetings.To make change happen on this scale, leadersneed to be increasingly effective at workingcollaboratively – not only with staff from acrossthe system but also with patients, people whouse services, elected politicians and citizens.Changes cannot be imposed but must besupported by the wider community. In FrimleyHealth and Care ICS, for instance, they haverecruited and developed ‘community champions’to reach out to communities, and in SurreyHeartlands they have established a residentpanel to get involved in service co-design.Leaders must also be able to establishgovernance structures which drive fasterchange, rather than being beholden to complexarrangements no longer fit for purpose. Peoplespoke about the need to sometimes breakup existing structures when they are notperforming, and go where the energy is strongestor where there are governance structures thatwork well already.“Systems leaders probably spent10 to 20 per cent of their time onpartnership activity 10 years ago.Now it needs to be 50 per cent tofocus effectively on collective aims.”“I don’t have a team like a traditionalleader. I am building one, but I don’thave a team to make things happen.That means core to my role is theability to influence others to dothings for you. You need to be goodat convincing people of the need todeliver an outcome and why we needto work together on something.For accountable care to workeffectively, key partners in the systemneed to build credible and resilientrelationships and be very clear andhonest with each other about whattheir collective focus and prioritiesshould be for the health andcare system.”(Local government leader, ICS)Leaders told us, however, that good stableleadership relationships take time to build. Someof the most successful ICSs have long-standingand trusting relationships across the senior levelin the system.Leaders spoke to us about how their roles wereoften highly challenging and isolating. Those newto a leadership role, in particular, need greatersupport and encouragement and a recognitionthat it takes time to develop the capabilities andbehaviours required to lead challenging systems.(Chief executive of NHS organisationand leader in ICS)7

ICS leaders are increasingly expected to supportthe development of MDTs, a process which isbeing accelerated under ICSs. In practice, thismeans you need to be good at building the rightconditions in which MDTs can thrive (e.g. workingwith leaders from other agencies to removebarriers to data-sharing and budget-pooling,devolving more decision-making to MDT leadersand encouraging joint staff development).Individual effectivenessLeaders of systems are unlikely to succeedin such a complex and diffuse operatingenvironment if they seek to control or directchange. Leadership in ICSs is more about settingan ambition and the direction of travel, the goalsand the behaviours expected. The onus is onleaders to build a distributed leadership model,and foster a culture of leadership at all levelswithin the system.“It can be described as tight andloose leadership – being clear thatwe expect certain outcomes andbehaviours and being tight aroundthis – but trusting your managersto get on with delivery and at timesletting them fail – being loose.This is absolutely key to it andbig learning for some of our moretraditional leaders – it is aboutinfluence, collaborative working,facilitation, trying to learn and shareunderstanding, and work acrossdifferent perspectives. What it is notabout is leading from the front, beingdirective, taking a command andcontrol approach – it is the oppositeof that.”(Chief executive of NHS organisation andleader in ICS)8

Case study: A new vision of care for people with frailtyor complex conditionsFrimley ICS set up a review of the way carewas provided for people with frailty or complexneeds.The design group produced a new vision of care:“The starting point for this workwas the question, how can wepool our expertise so that serviceswe develop are built on the bestof what is happening locally andnationally?”R espect our choices and capabilities andencourage us to influence the care andsupport we receive.P romote health, wellbeing and the quality ofour lives.H elp us maintain independence for as longas possible.B e driven by our goals and ambitions andthose of our family and carers.B e easy to navigate day or night.(Senior clinician, ICS)M ake the right thing to do the easy thingto do.The review involved CCGs, the local authorities,NHS foundation trusts, the ambulance service,patient groups, the voluntary sector and thelocal community.B e holistic and integrated, making bestuse of the strengths of the local systemincluding the voluntary sector.The design group involved around 40 clinicians,social care staff, and people from local patientand community groups. A steering group wasalso established.B e high quality.R equire us to tell our story only once bysharing our information securely with thosewho need to know.A key theme throughout was an emphasison treating frailty more like other long-termconditions. Thus, rather than waiting for a crisisto happen and then responding t

and leadership of integrated care systems. This research will inform the Leadership Academy’s long-term plans for supporting leaders in integrated care systems. This paper, aimed at chief executives, directors and senior manage