Transcription

Family-Centered, Evidence-Based Phototherapy DeliveryKinga A. Szucs and Marc B. RosenmanPediatrics 2013;131;e1982; originally published online May 13, 2013;DOI: 10.1542/peds.2012-3479The online version of this article, along with updated information and services, islocated on the World Wide Web 31/6/e1982.full.htmlPEDIATRICS is the official journal of the American Academy of Pediatrics. A monthlypublication, it has been published continuously since 1948. PEDIATRICS is owned,published, and trademarked by the American Academy of Pediatrics, 141 Northwest PointBoulevard, Elk Grove Village, Illinois, 60007. Copyright 2013 by the American Academyof Pediatrics. All rights reserved. Print ISSN: 0031-4005. Online ISSN: 1098-4275.Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org by Raylene Phillips on July 13, 2013

Family-Centered, Evidence-Based Phototherapy DeliveryabstractAUTHORS: Kinga A. Szucs, MD, FAAP and Marc B.Rosenman, MDJaundice develops in most newborn infants and is one of the mostcommon reasons infants are rehospitalized after birth. AmericanAcademy of Pediatrics clinical practice guidelines strongly supportthe recommendation that clinicians promote and support breastfeeding. Recognizing that the disruptions associated with phototherapyinterfere with breastfeeding, the challenge often faced by clinicians ishow to provide effective phototherapy while supporting evidencebased practices, such as rooming-in, skin-to-skin contact, and breastfeeding. We report here on a case that reflects a common clinicalscenario in newborn medicine in order to describe a technique forproviding phototherapy while maintaining evidence-based practices.This approach will assist clinicians in providing best-practices andfamily-centered care. Pediatrics 2013;131:e1982–e1985Department of Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine,Indianapolis, IndianaKEY WORDSphototherapy, hyperbilirubinemia, kangaroo care, breastfeedingABBREVIATIONAAP—American Academy of PediatricsDr Szucs conceptualized and designed the report, drafted theinitial manuscript, revised the manuscript, and approved thefinal manuscript as submitted; and Dr Rosenman assisted in theconcept and design of the report and in drafting and revisingthe manuscript and approved the final manuscript as 2012-3479doi:10.1542/peds.2012-3479Accepted for publication Feb 25, 2013Address correspondence to Kinga A. Szucs, MD, FAAP, Departmentof Pediatrics, Indiana University School of Medicine, FamilyBeginnings, Wishard Health Services, 1001 West 10th St,Indianapolis, IN 46202. E-mail: kszucs@iupui.eduPEDIATRICS (ISSN Numbers: Print, 0031-4005; Online, 1098-4275).Copyright 2013 by the American Academy of PediatricsFINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they haveno financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.FUNDING: No external funding.e1982SZUCS and ROSENMANDownloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org by Raylene Phillips on July 13, 2013

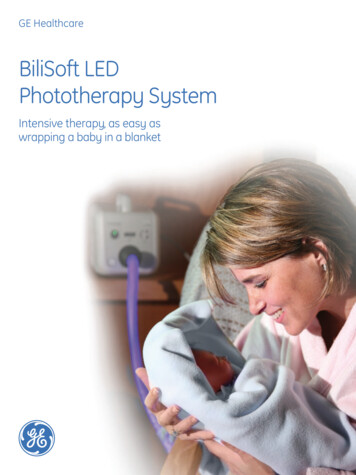

CASE REPORTJaundice develops in most newborninfants1–3 and is one of the most common reasons infants are rehospitalizedafter birth.4 The focus of the AmericanAcademy of Pediatrics (AAP) guideline onthe management of hyperbilirubinemiain newborns 35 weeks of gestation is“to reduce the incidence of severehyperbilirubinemia and bilirubin encephalopathy . . . while minimizing therisks of unintended harm such as . . .decreased breastfeeding.”1,2 The number 1 key element listed in this AAPclinical practice guideline stronglysupports the recommendation in manyother AAP policy statements that clinicians promote and support breastfeeding.1,2 Recommendation 1.0 is to“advise mothers to nurse their infantsat least 8 to 12 times per day for the firstseveral days.”1 The practice guidelinealso recommends steps for appropriaterisk assessment and follow-up, andphototherapy when indicated.It was recognized in the 1980s that thedisruptions associated with phototherapy interfere with breastfeeding.5,6When bili blankets were introduced inthe early 1990s and were comparedwith conventional phototherapy, one ofthe benefits cited was the possibilityof “the mother handling and nursingher infant during phototherapy,”7 andphototherapy at home also offered thepossibility of less interference withbreastfeeding.8 (Note that risk factorsfor hyperbilirubinemia include but arenot limited to isoimmune hemolyticdisease and glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency and that theAAP recommends that “home phototherapy should not be used in any infant with risk factors.”1)Two decades later, US hospitals’ methods for the delivery of phototherapyvary. On the basis of responses to arecent questionnaire on the AcademicPediatric Association Newborn NurseryDirectors Special Interest Group listserv, some hospitals transfer all infantswho require phototherapy to the NICU.Other hospitals treat infants in thenewborn nursery in an isolette, in themother’s room in an isolette, or in themother’s room in an open bassinet.Practicing rooming-in 24 hours per dayis one of the steps in the World HealthOrganization/United Nations Children’s Fund’s “Ten Steps to SuccessfulBreastfeeding.”9 The Ten Steps, andspecifically rooming-in, were endorsed by the AAP and other professional organizations.10–12 In infantsrooming-in compared with those notrooming-in, breastfeeding frequencywas significantly higher, supplementation was lower, and weight gain washigher.13 Skin-to-skin contact (kangaroomother care) assists with mother-infantattachment and bonding and facilitates breastfeeding. Multiple studieshave shown that skin-to-skin contactprovides thermoregulation to infants.14,15 In term infants it helps withneurobehavioral adaptation and hasa beneficial effect on the neurophysiologic organization of the developingbrain; kangaroo care infants spendmore time in quiet sleep states andless time in fussy or crying states.15Kangaroo care reduces morbidityand mortality, and at 6 months’ corrected age, the infants scored higheron the Bayley Mental DevelopmentalIndex.14,15 The AAP’s evidence-basedrecommendations include early skin-toskin contact and exclusive breastfeeding; if phototherapy is required,continuous breastfeeding is recommended.We report here on a case that reflectsa common clinical scenario in newbornmedicine to describe a technique wehave developed for providing phototherapy while maintaining evidencebased practices in newborn care. Thepolicy of Indiana University–PurdueUniversity Indianapolis is that individual case reports are not reviewed by itsinstitutional review board.PATIENT PRESENTATIONA male infant with an estimated gestational age of 39 weeks was born toa 29-year-old gravida 1, para 1 mothervia spontaneous vaginal delivery. Themother has an O blood type that is Rhpositive and antibody negative. We ordered a blood type and direct Coombstest for the infant. The infant was notedto have an A blood type that was Rh anddirect Coombs positive. This situationplaced the infant at risk of hemolysis,including hyperibilirubinemia and anemia, so we ordered a hematocrit, areticulocyte count, and a serum bilirubin level measurement. The hematocrit was 39%, the reticulocyte countwas 11%, and serum bilirubin was 6.8mg/dL at 8 hours of life and 11 mg/dL at24 hours of life. The infant was startedon intensive phototherapy by usingboth a neoBLUE LED phototherapy device (Natus Medical Inc, San Carlos, CA)on the high setting (delivers .30 uW/cm2 per nm)16 and a GE HealthcareOhmeda BiliBlanket Plus (OhmedaMedical, Columbia, MD; delivers up to45 uW/cm2 per nm).17 The light sourcefor the blanket is a halogen bulb, andthe blanket contains 2400 optic fiberswoven together. Infrared and UV filtersmaintain the light within the desired400- to 550-nm range.17The method we use at our institution isas follows: The phototherapy lights areadministered in the mother’s room. Theinfant is placed on the mother’s ventrum. The phototherapy light is placedabove the infant. To ensure the correctdistance between the phototherapylight and the infant, we place a tapemeasure on the device (Fig 1). For ourdevice, the correct distance for thelight source is 12 inches (30.5 cm) fromthe infant. The light source can be adjusted both horizontally and vertically,as well as tilted over a wide range ofangles. Both mother and infant wearprotective eyewear (mother: Amber LensSafety Glass [Grainger International Inc,PEDIATRICS Volume 131, Number 6, June 2013Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org by Raylene Phillips on July 13, 2013e1983

FIGURE 1The infant under the phototherapy light with a biliblanket while on the mother’s chest.Lake Forest, IL]; infant: eye shield). Thebili blanket is placed below the infant(Fig 1). We encourage frequent breastfeeding, review early feeding cues withthe mother, and evaluate (by a trainedprovider, every shift) the latch and milktransfer. The subsequent serum bilirubinlevels were 9 mg/dL at 36 hours and 8mg/dL at 48 hours. Figure 2 depicts theinfant without the bili blanket.DISCUSSIONAs Bergman18 has pointed out, “skin-toskin contact is the natural ‘habitat’ forhuman infants.” When separated fromthis contact, newborns’ stress hormonelevels increase, and they cry. By providingphototherapy on the mother’s chest, thisstress response can be avoided.Some centers provide phototherapy inthe mother’s room, in an open bassinet.One of the difficulties encountered inthese situations is that the infant criesand the family takes the infant out fromunder the lights. The family might become frustrated with the process, andFIGURE 2The infant under the phototherapy light and inskin-to-skin contact with the mother.e1984the bilirubin levels will not decrease asdesired. Clinicians also may expressconcern that the infant will be takenout from under the lights for too long.One idea that some health care providers have is to take the infant outfrom under the light only for feeding.However, that approach may substantially reduce the phototherapy dose.De Carvalho et al19 found that morefrequent feedings were associated withlower bilirubin levels. Eleven feedings in24 hours resulted in the lowest bilirubinvalues. Infants spend a significant amountof time on the breast, and for casesof severe hyperbilirubinemia the bestapproach is to have them exposed tothe phototherapy light continuously. Ifthe mother is asleep, another familymember (eg, father, grandparent) whileseated in a chair can hold the infant inskin-to-skin contact.The nursing staff does not continuouslyobserve the infants. Bedside safetychecks are performed every 6 hours bythe nursing staff. With each check, thenurses document the various itemssuch as “biliblanket,” “bililight,” “equipment settings verified,” “eye patches inplace/secure,” and so forth.Readers may ask about the risk thata mother or other family member mightfall asleep while holding the infant. Wehave not had any of our nurses finda mother asleep with her infant in bedduring phototherapy. Because skin-toskin contact is encouraged for allinfants in our institution, whether or notthey are receiving phototherapy, therisk of a mother (or other family member) falling asleep is not limited tothe infants receiving phototherapy. TheAAP policy statement encourages “direct skin-to-skin contact . . . throughoutthe newborn period.”10 Our institution(as is probably the case at many otherinstitutions) also has a local policy thatencourages skin-to-skin contact. Mothers (or fathers or other family members)are encouraged to have continuous skin-to-skin contact with their infants whenshe (or the father or other family member) is not asleep. Whether or not theinfant has been prescribed phototherapy, the family is instructed to placethe infant in the bassinet when the adultfamily member who was holding the infant decides to sleep.At our hospital, when we found thatcaregivers tended to take the infantsout from under the lights when theywere crying (often at night) and forfeeding, we arranged for protective eyecover to be available for the mothers (orfathers), who can then hold the infantwhile under the phototherapy light. Ifthe mother is awake, she (in her bed)holds the infant, with both she and infant wearing protective eyewear. Thenurse then aims the phototherapy lightover the infant. It is important to checkthe instruction manual of the particular phototherapy device one is using(regarding how far the baby should beplaced from the light source, etc.).When appropriate, it is important tomake sure that the light is on the “high”setting, if there is such a setting. Withthe neoBLUE there is no need for additional “banks” of light. (In the past,we had the option of 1, 2, or 3 banks oflight.) When all caregivers in the roomare asleep, the infant is placed in thebassinet with the light above and theblanket below.If the infant has high bilirubin levels, weuse neoBLUE on the “high” setting fromabove and a bili blanket placed belowthe infant. If the bilirubin level is lower,and the family cannot cope with thelight (which is rare, because mostfamilies like the fact that they can holdthe infant while he or she is receivingphototherapy), we have used 1 blanketfrom above and another from belowthe infant, or just 1 blanket. However,for infants with high bilirubin levels,bili blankets alone do not seem to workas well; it is more effective to includea light.20SZUCS and ROSENMANDownloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org by Raylene Phillips on July 13, 2013

CASE REPORTOur institution’s phototherapy policyincludes the stipulation that all clothing items, including hats, be removedfrom the infant, because the newborn’shead has a relatively large surfacearea. Diapers remain on the infant. Wehave had no problems with temperature regulation. It is our practice tocheck the mother’s and infant’s temperatures every 6 hours. We have nothad any problems with hypothermia inthe infants or overheating of themothers or infants while using thismethod of phototherapy delivery.The protective glasses are light-weightand comfortable, similar to a pair ofa tiny fraction of her lifetime exposure.Still, out of an abundance of caution, werequire that the mothers wear theprotective amber glasses.sunglasses. The mothers (and otherfamily members) in our institution havenot minded wearing them. The purposeof the amber glasses is to shield themother’s retinas from the blue light. Wecould find no published scientific evidence that, if the mother were notwearing amber glasses, the short-term(a few days’) exposure to phototherapylight would pose a risk. Although it hasbeen hypothesized that blue light maybe a risk factor for age-related maculardegeneration, the evidence for an association has not been firmly established.21 The exposure that the mothermight receive in the hospital is probablyThe most recent US data show a 76.9%breastfeeding initiation rate.22 Thephototherapy method described herecan help support evidence-based methods for large numbers of infants. Families appreciate the solution of holdingthe infant while under the lights (because the infant stops crying) and arehappy with this approach for phototherapy. Practitioners will find thismethod of phototherapy delivery helpfulin providing family-centered care.8. James JM, Williams SD, Osborn LM. Discontinuation of breast-feeding infrequentamong jaundiced neonates treated athome. Pediatrics. 1993;92(1):153–1559. World Health Organization/United NationsChildren’s Fund. Ten steps to successfulbreastfeeding. Available at: www.unicef.org/newsline/tenstps.htm. Accessed November 11, 201210. Section on Breastfeeding. Breastfeedingand the use of human milk. Pediatrics.2012;129(3). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/129/3/e82711. Academy of Breastfeeding MedicineProtocol Committee. ABM clinical protocol #7: model breastfeeding policy(revision 2010). Breastfeed Med. 2010;5:173–17712. American College of Obstetricians andGynecologists Committee on Health Carefor Underserved Women; Committee onObstetric Practice. Special report fromACOG. Breastfeeding: maternal and infantaspects. ACOG Clin Rev. 2007;12(suppl 1):1S–16S13. Yamauchi Y, Yamanouchi I. The relationshipbetween rooming-in/not rooming-in andbreast-feeding variables. Acta PaediatrScand. 1990;79(11):1017–102214. Feldman R, Eidelman AI, Sirota L, Weller A.Comparison of skin-to-skin (kangaroo) andtraditional care: parenting outcomes andpreterm infant development. Pediatrics.2002;110(1 pt 1):16–2615. Ferber SG, Makhoul IR. The effect of skin-toskin contact (kangaroo care) shortly afterbirth on the neurobehavioral responses ofthe term newborn: a randomized, controlledtrial. Pediatrics. 2004;113(4):858–86516. neoBLUE LED Phototherapy user manual. SanCarlos, CA: Natus Medical Inc. Available at:www.natus.com. Accessed October 26, 201217. Healthcare GE. Products and solutions,phototherapy. Available at: ducts/phototherapy/biliblanket plus.html.Accessed January 21, 201318. Bergman N. Restoring the original paradigm for infant care. Available at: www.skin.kangaroomothercare.com/prevtalk01.htm. Accessed November 10, 201219. De Carvalho M, Klaus MH, Merkatz RB.Frequency of breast-feeding and serumbilirubin concentration. Am J Dis Child.1982;136(8):737–73820. Mills JF, Tudehope D. Fibreoptic phototherapy for neonatal jaundice. CochraneDatabase Syst Rev. 2001;1(1):CD00206021. Margrain TH, Boulton M, Marshall J, SlineyDH. Do blue light filters confer protectionagainst age-related macular degeneration?Prog Retin Eye Res. 2004;23(5):523–53122. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Breastfeeding among U.S. childrenborn 2000-2009, CDC National ImmunizationSurvey. Available at: www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding/data/nis data/. Accessed November 11, 2012REFERENCES1. American Academy of Pediatrics Subcommittee on Hyperbilirubinemia. Managementof hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant 35 or more weeks of gestation. Pediatrics. 2004;114(1):297–3162. Maisels MJ, Bhutani VK, Bogen D, NewmanTB, Stark AR, Watchko JF. Hyperbilirubinemia in the newborn infant . or 35weeks’ gestation: an update with clarifications. Pediatrics. 2009;124(4):1193–11983. Academy of Breastfeeding Medicine Protocol Committee. ABM clinical protocol #22:guidelines for management of jaundice inthe breastfeeding infant equal to or greaterthan 35 weeks’ gestation. Breastfeed Med.2010;5(2):87–934. Newman TB, Liljestrand P, Jeremy RJ, et al;Jaundice and Infant Feeding Study Team.Outcomes among newborns with total serum bilirubin levels of 25 mg per deciliteror more. N Engl J Med. 2006;354(18):1889–19005. Kemper K, Forsyth B, McCarthy P. Jaundice,terminating breast-feeding, and the vulnerable child. Pediatrics. 1989;84(5):773–7786. Elander G, Lindberg T. Hospital routines ininfants with hyperbilirubinemia influencethe duration of breast feeding. Acta Paediatr Scand. 1986;75(5):708–7127. Tudehope D, Crawshaw A. Fibreoptic versusconventional phototherapy for treatment ofneonatal jaundice. J Paediatr Child Health.1995;31(1):6–7PEDIATRICS Volume 131, Number 6, June 2013Downloaded from pediatrics.aappublications.org by Raylene Phillips on July 13, 2013e1985

Family-Centered, Evidence-Based Phototherapy DeliveryKinga A. Szucs and Marc B. RosenmanPediatrics 2013;131;e1982; originally published online May 13, 2013;DOI: 10.1542/peds.2012-3479Updated Information &Servicesincluding high resolution figures, can be found 31/6/e1982.full.htmlReferencesThis article cites 16 articles, 7 of which can be accessed nt/131/6/e1982.full.html#ref-list-1Permissions & LicensingInformation about reproducing this article in parts (figures,tables) or in its entirety can be found online /Permissions.xhtmlReprintsInformation about ordering reprints can be found misc/reprints.xhtmlPE

on intensive phototherapy by using both a neoBLUE LED phototherapy de-vice(NatusMedicalInc,SanCarlos,CA) on the high setting (delivers .30 uW/ cm2 per nm)16 and a GE Healthcare Ohmeda BiliBlanket Plus (Ohmeda Medical, Columbia, MD; delivers up to 45 uW/cm2 per nm).1