Transcription

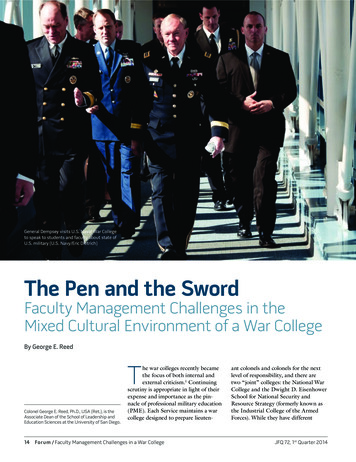

General Dempsey visits U.S. Naval War Collegeto speak to students and faculty about state ofU.S. military (U.S. Navy/Eric Dietrich)The Pen and the SwordFaculty Management Challenges in theMixed Cultural Environment of a War CollegeBy George E. Reedhe war colleges recently becamethe focus of both internal andexternal criticism.1 Continuingscrutiny is appropriate in light of theirexpense and importance as the pinnacle of professional military education(PME). Each Service maintains a warcollege designed to prepare lieuten-TColonel George E. Reed, Ph.D., USA (Ret.), is theAssociate Dean of the School of Leadership andEducation Sciences at the University of San Diego.14Forum / Faculty Management Challenges in a War Collegeant colonels and colonels for the nextlevel of responsibility, and there aretwo “joint” colleges: the National WarCollege and the Dwight D. EisenhowerSchool for National Security andResource Strategy (formerly known asthe Industrial College of the ArmedForces). While they have differentJFQ 72, 1st Quarter 2014

cultures at the institutional level, theyshare some common challenges andopportunities. This article examinessome of those challenges from theperspective of an administrator, a voicethat is often missing from the currentdialogue, which seems to be dominatedby journalists, bloggers, and civilianprofessors who do their work at theuncomfortable intersection of academicand military cultures.2This submission represents a friendlycritique submitted by one who benefitedgreatly as a student and then, after completing a fully funded doctoral program,as a faculty member. This perspective isinformed by 6 years as a faculty memberand a course director for two segmentsof the core curriculum at the U.S. ArmyWar College, followed by an equal timeas a civilian faculty member at a doctoraldegree conferring university and now asan administrator. Even with an admittedlyfavorable viewpoint, it is not hard to seethat there is room for systemic improvement. After a brief review of contemporarycritiques focused on the war colleges, thearticle turns to some observations from anadministrator’s perspective.War Colleges under FireFormer Washington Post journalist andauthor Thomas Ricks launched a publicsalvo against the war colleges in a seriesof ForeignPolicy.com blogs where heactually called for their closure, describing them as both expensive and secondrate. While his criticism is sometimeshyperbolic and tends to be disregardedby those within the system, he raisessome good points and serves as awatchdog of sorts as evidenced by hisrecent accounting of personnel changesthat resulted in the reduction of civilianprofessor positions at the Army WarCollege.3Douglas Higbee provided a usefulcritical anthology from authors rangingacross the system of professional militaryeducation.4 Daniel Hughes’s depictionof the Air War College in that edited volume was strident in highlighting a nastystrain of anti-intellectualism, ultraconservatism, Christian nationalism, and alargely disinterested student body.5 WhileJFQ 72, 1st Quarter 2014some might reject the observations of anoutsider such as Ricks, Hughes servedfor 18 years at the Air War College, thusproviding an insider view. Some might beinclined to dismiss him as a disgruntledformer employee, but regardless of hismotivation, there is cause for concern ifhis observations have any merit.Robert Scales, a retired two-star general and former commandant of the ArmyWar College, raised an alarm by observing that the military could become “toobusy to learn.”6 His essay did not addressthe war colleges specifically except fornoting that the average age of attendeeshas increased from 41 to 45, making anexpensive educational experience moreof a preparation for retirement than aplatform for leadership at higher levels.He decried the wane of experienced officers as instructors in the system of PME.His critique echoed some of the concernsvoiced by Ricks when he suggested thata bias for action over learning and anorganizational malaise in the schools havemade them an “intellectual backwater.”His solution is to change the military’sreward system to elevate soldier-scholarsrather than denigrate them. He advocated a return to the day when uniformedofficers rather than civilian instructorsand contractors are assigned to theschoolhouse, not because their careers areat a dead end, but as career-enhancingassignments on the way to even higherlevels of responsibility.In an especially helpful and recentbook, Joan Johnson-Freese examinesthe war colleges and succinctly capturedwhat she terms “overriding institutionaland cultural issues” that hinder the accomplishment of their educational goals.7A military penchant for training overeducation, counterproductive clashes between military and civilian culture, studentattitudes, administrators who lack experience in running educational institutions,short-term contracts for civilian faculty,administrative bloat, and lack of facultycontrol of the curriculum all make her listof detractions. She is an insider who servedon the faculty of the Air War College andAsia-Pacific Center for Security Studiesand is currently serving at the Naval WarCollege. She rightly points to areas wherethe war colleges excel, and because of thelevel tone of her work, she is much harderto dismiss than some others who havecontributed to the topic.Comparing PME to CivilianHigher EducationIt is important to note that comparingthe war colleges to traditional civilian graduate institutions is a bit of an“apples to oranges” exercise. The bestgraduate program at a top-tier university would, in many respects, be a poorsubstitute for what should happen atthe war colleges. The model for thewar colleges is much more akin to thatof a professional school (for example,law or medicine) where sophisticatedcraft knowledge is blended to a lesserdegree with disciplinary forays morecommon to colleges and universities.The war colleges are not designed toproduce scholars and researchers; theydevelop operators and leaders, albeitwith knowledge and skills that aresometimes derived from graduate-leveleducation. The adult learning model,seminar method, use of case studiescontextually appropriate to a uniquegroup of experienced practitioners, andthe many opportunities to engage inno-holds-barred professional discussions with a parade of flag officers andcivilian officials are bright spots thatshould not be underestimated for theirpositive impact on future senior militaryleaders. It is vital to have a place wheremilitary officers can delve deeply intothe nuances of their profession andmost importantly plumb the tensions,intricacies, and limitations of operatinga large standing military in a democracy.If done properly, that very processcan serve as a crucial protection of theRepublic. Uninformed and undereducated officers who control vast amountsof military power can fall, or be led, intoserious mischief.Here is a dirty little secret we shouldconsider as we seek the goodness that resides in our comparison group of top-tiercivilian universities. Great and sometimesinordinate emphasis is placed on researchand publication, which can detract fromeffective teaching. The ability to conductReed15

research is a strong motivator for first-ratefaculty members who wish to be tenured.Good teaching, however, is not usuallythat high a priority, especially at researchfocused universities. Faculty memberssavor the discretionary time to pursuetheir own interests and require even moretime to locate and complete extensiveand complicated applications for grants tofund that research. There is often a muchlower emphasis on high-quality teaching.The drive for tenure and how to achieveit consumes the attention and energy ofjunior faculty members, generating greatstress. While most tenure evaluationschemes include teaching, scholarship,and service as elements of review, few aredenied tenure due to mediocre teachingevaluations or lack of service on universitycommittees. Research and publicationare the long poles in the tent. Havingfirmly established the primacy of researchthrough the socialization process, themore successful faculty members are,the less they will be seen in a classroom.Teaching assistants take up the slack.Despite the prestige of some civiliancolleges and universities, many teaching practices there are not particularlyeffective.Tenure is a double-edged sword. ThePME system does not seem to recognizeits importance in recruiting and retaininghigh-quality faculty members. Tenureis the brass ring of a budding academiccareer—a designation that delineates theserious academic from the part-timer—the professional from the amateur. Acolleague recently suggested that no selfrespecting competitive academic wouldbe willing to join the faculty of an institution that did not offer tenure unless therate of compensation and likelihood ofcontract renewal were so high as to offsetthe attendant loss of security. Short-termcontracts subject to renewal at the whimsof nonacademics and the vagaries of avacillating defense budget are no wayto hire the best and brightest. There isalso a relationship between tenure andacademic freedom. Those who cannot befired for their opinions as long as they areexpressed within the norms of responsibleacademic practice can become effectiveand useful gadflies. The lack of such16protection can have a chilling effect onspeaking truth to power,8 a role the warcolleges might well serve.Having noted the necessity of tenureor a tenure-like system for both academicfreedom and talent management, weought to also take notice of the otheredge of the sword. The accounts ofabuses by senior faculty members who areprotected by tenure but are unproductive or simply uncivil in their practicesare legion in higher education.9 Indeed,there are opportunities for post-tenurereview at some institutions or triggeredreviews prompted by serious misconduct,but they are rare and a great deal of poorpractice is tolerated before considerationis given to initiating them. Behavior isroutinely tolerated in the system of civilian education that would invariably andjustifiably involve contract termination ornonrenewal in the PME system.Faculty Talent ManagementIt is appropriate to focus on the conceptof academic talent management becauseof the centrality of the quality of thefaculty to the effectiveness of any educational institution including the PMEsystem.10 This concept seems to belost on some administrators in militaryorganizations. That is understandablein a system where Servicemembers areeasily exchanged or replaced and thepersonnel system routinely generatesreplacements for vacancies on demand.Servicemembers engage in permanentchange of station moves regularly, andthe kind of personnel churn that woulddebilitate most educational institutionsis accepted as routine. No one personis irreplaceable in a military formation, and it is unknown when anothermight become a casualty. Attracting andretaining academic talent, however, is acompetitive sport that the PME systemplays at significant disadvantage. Hiringand retention are also some of the mostimportant activities an administrator engages in. Recent experience asthe chair or member of several searchcommittees for both junior and seniorfaculty positions provokes reflection onthe differences when one is recruitingacademics. Let us briefly examine sevenForum / Faculty Management Challenges in a War Collegeways the PME system is disadvantagedin the marketplace for academic talentin addition to the issue of tenure: accessto outside employment, compensation,copyright restrictions, quality of infrastructure, ability to teach in an area ofexpertise, faculty governance and curriculum oversight, and hiring practices.Access to Outside Employment. In theFederal system, outside employment iseither prohibited outright or significantlyconstrained by 5 C.F.R., Part 2635,Subpart F.11 At the very least, permission must be obtained ahead of timeand in some cases an ethics finding froman attorney is advisable. University anddepartmental policies on outside employment vary as do practices by discipline,but many professors significantly augment their salaries through consultingor additional teaching. In many civilianschools, outside employment is not onlypermitted but also encouraged as a meansof expanding the reputation and reachof the institution. Faculty members arepermitted to engage in outside employment without restriction provided theygive first priority to their university duties. Since professors are not expected tobe in their offices on a daily basis, facultymembers who strategically construct theirteaching schedules can build a lucrativeconsulting practice. Because they areserving 9-month contracts, faculty members have time in the summer to pursueoutside work or consulting. Facultymembers who choose to teach coursesduring summer months or teach morethan their assigned faculty load are paida healthy stipend. Moreover, at civilianinstitutions, if faculty members are askedto perform additional work beyond theircontractual teaching load, such as providing presentations or workshops, theyare paid extra, usually in the form of astipend or honorarium. Howard Wiardareports being frequently “tasked” to givelectures beyond the terms of his contractat the National War College.12 It wouldnot occur to most administrators ofmilitary educational facilities to provideadditional stipends on top of salary forsuch activities.Compensation. The war collegesplace emphasis on pay equity acrossJFQ 72, 1st Quarter 2014

departments with allowance for seniority. In one sense that is appropriate sinceinstructors are doing the same kinds ofdaily work. While Federal pay scales lookgenerous in some fields (for example,history and the humanities), in otherfields they are not nearly as attractive. Atcivilian universities it is accepted withoutquestion that management professorsin the school of business will receivemuch higher salaries than history professors in the college of arts and sciences.That holds true within interdisciplinarydepartments as well. A professor whocomes from the field of public policywill be paid more than one who comesfrom education even though they areworking in the same department. Civilianinstitutions sometimes find creative waysto compensate faculty members beyondsalary. Home-buying assistance, noncontributory retirement plans, mass transitassistance, reduced teaching load, andtuition remission for family members arebut a few examples.Copyright Restrictions. The application of copyright rules varies by Serviceand interpretations vary by legal advisor,but the general rule is that materials produced by employees of Federal agenciesare considered to be in the public domainand are not subject to copyright protection. Work that is prepared by an officeror employee of the U.S. Governmentcannot by copyrighted in accordancewith Chapter 17 U.S. Code § 105.13 Aconservative interpretation of this statutecan have a retarding effect on scholarlypublication. Most scholarly journals willonly publish on the basis of copyrightownership that is conferred by the author.Faculty members in the PME systemhave in some cases gone to great lengthsto establish that their published worksare not works of the government. Theywill work at home on personal computers and assiduously avoid materials orresources that could be construed to bepart of their government work. In somecases, there is institutional winking goingon around this subject since publishingenhances the prestige of the institution.None of this is an issue in civilian academic institutions. Research funded byuniversity grants, or inherently part ofJFQ 72, 1st Quarter 2014classroom or scholarly effort, is fully subject to copyright by the civilian professor.Academic publishing is not particularlylucrative, but royalties from publishedworks can augment salaries.Quality of Infrastructure. A goodnumber of the facilities in the PMEsystem, at least as far as the war collegesare concerned, are aging, retrofitted, andin some cases overstuffed. Many of thefaculty members share offices or cubicles.For military personnel who have spentsignificant time deployed or in the field,such accommodations are nothing tocomplain about, but the quality of facilities is an element of the larger issue ofwork environment and quality of life.College campuses vary along a spectrumfrom functional to beautiful, but it wouldnot be hard to assert that civilian collegesand universities have an edge in this category. Faculty members at the Army WarCollege shared small offices with otherfaculty members. Consultations with students involved whispered conversationsor gracious exits by office mates.Ability to Teach in an Area ofExpertise. Many academics are specialists. They strive to become experts anddevelop a deep level of knowledge aboutsomething. That something mightchange over time, and their breadth ofknowledge might expand, but goodacademics work hard to establish andmaintain a strong foundation in disciplinary knowledge. Entire academic careersare made on niche knowledge that canbe arcane in some cases but valuable forits depth in others. Former dean of theArmy War College Jeffrey McCauslandonce sagely suggested that the first loyalty of academics is to their disciplines.My economist colleague can always becounted on to advocate for what that discipline brings to the scholastic table, andanother colleague who has built a careerin K-12 education speaks forcefully forthat program.Now imagine a new teacher arrivingat a war college to find out he is to teachsubjects far outside the boundaries of hisdiscipline and, in fact, the only time hewould have the opportunity to teach inhis beloved area of expertise is during anabbreviated elective period. A personalexample might illustrate the point. Igraduated with a Ph.D. in public policyanalysis and administration, a subject Icame to appreciate and enjoy. My teaching duties largely centered on threeelements of the core curriculum: the firstblock addressed cognitive skills associated with strategic thinking, the secondwas oriented to strategic leadership, andthe third focused on defense systems andprocesses such as Department of Defensebudgeting, force management, andacquisition. While I came to thoroughlyenjoy the first two blocks and lovedteaching in general, I detested the blockof instruction on defense processes. Whilesuch processes are arguably importantand something that senior military leaders should understand (points that arecontinuously drummed into the heads ofthe students who were not particularlyenthusiastic about the subjects either),they were outside my range of expertiseand my boundaries of interest.Faculty Governance andCurriculum Oversight. The war collegesplace inordinate emphasis on the curriculum that is derived largely from the topdown. At most civilian universities, thecurriculum belongs to the faculty. Thereare processes for faculty voice and indeedveto when it comes to new programs andcourses, course modifications, and cancellations. Faculty control of the curriculumis a jealously guarded prerogative that canfrustrate administrators. Administratorshave an important role, especially regarding resource considerations andlimitations, but getting heavy handedwith curricular issues is a pathway to avote of no-confidence from the faculty,a concept that is foreign in PME. Thereare advantages to this kind of bottom-upsystem. It is easy to argue that those whoare experts in their fields ought to controlthe content of their courses. It can admittedly also be a recipe for stagnation andimmunity to necessary change. Whilethere is a variable amount of faculty voicein the curriculum at the war colleges, itis remarkably diminished in comparisonto many civilian institutions of highereducation. The war colleges serve onecustomer, the Department of Defense,and responsiveness to the needs of thatReed17

customer drives top-down processes suchas joi

its importance in recruiting and retaining high-quality faculty members. Tenure is the brass ring of a budding academic career—a designation that delineates the serious academic from the part-timer— the professiona