Transcription

Volume 19 Issue 2An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education ProgramCocoa’s Impact on ChildrenMap It: Cocoa in West AfricaPost Reprint: “Cocoa’s child laborers” Informational Graphics: Explain the Business of Cocoa: Use Mathematics,Maps and Meaningful Graphics Student Activity: Photographs Tell a Story November 11, 2019 2020 THE WASHINGTON POST

Volume 19 Issue 4An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education ProgramIntroducTIon.Watch 10-year-olds playing. Or the 15-year-olds working on a groupproject in your classroom. Can you image more than half of the childrenin your school working daily, with machetes or in crops sprayed withinsecticides? According to the U.S. Labor Department, “a majority ofthe 2 million child laborers in the cocoa industry are living on theirparents’ farms, doing the type of dangerous work that internationalauthorities consider the ‘worst forms of child labor.’”Fewer, but still children, have left theirfamilies and countries to work oncocoa farms.Activities in Resource Guide 1 (“FromPlate to Soil”) and this Resource Guide(“Explain the Business of Cocoa” and“Photographs Tell a Story”) togetherencourage students to think about thefoods and sweets they consume as relatedto child labor and ways to communicate toothers what they learn in Washington Postinvestigative articles and photographs.kcabHishurts, e isand h y.hungrWashington Post reporter Peter Whoriskey and photojournalist SalwanGeorges traveled to Ivory Coast to observe cocoa farms in three villages.They interviewed 12 boys, 13- to 18-year-olds, to put faces to the figures.A few of the older boys had no desire to return home; they had scrapedtogether money and cleared forest land to begin a cocoa farm. But manyothers were not paid, had lost their dreams of education and a betterlife, and lived in poor condition. What should the cocoa industry andgovernments and consumers do for these boys? The ones whose backshurt and are hungry.Jamuary 14, 20202 2020 THE WASHINGTON POST

Volume 19 Issue 4An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education ProgramMap It: Cocoa in West AfricaFarms in the Ivory Coast form the world’s most important source of cocoa and are the setting for an epidemic ofchild labor that the world’s largest chocolate companies promised to eradicate nearly 20 years ago.laris karklis/the washihgton postA chart showing Ivory Coast as producingthe most cocoa in the world is displayedat the Choco-Story, Museum of Cocoa andChocolate in Brussels.Jamuary 14, 20203 2020 THE WASHINGTON POST

Volume 19 Issue 4An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education ProgramCocoa’s child laborersMars, Nestlé and Hershey pledged nearly two decades ago to stop using cocoaharvested by children. Yet much of the chocolate you buy still starts with child labor.story byCoast since he was 10. The other fourboys say they are young, too — onesays he is 15, two are 14 and another,13.Abou says his back hurts, and he’shungry.“I came here to go to school,” Abousays. “I haven’t been to school forfive years now.”Peter Whoriskeyphotos byandSalwan Georges Published on June 5, 2019GUIGLO, Ivory Coast — Five boysare swinging machetes on a cocoafarm, slowly advancing against awall of brush. Their expressions aredeadpan, almost vacant, and theyrarely talk. The only sounds in the stillair are the whoosh of blades slicingthrough tall grass and metallic pingswhen they hit something harder.Each of the boys crossed theborder months or years ago from theimpoverished West African nationof Burkina Faso, taking a bus awayfrom home and parents to IvoryCoast, where hundreds of thousandsof small farms have been carved outof the forest.These farms form the world’s mostimportant source of cocoa and are thesetting for an epidemic of child laborthat the world’s largest chocolatecompanies promised to eradicatenearly 20 years ago.“How old are you?” a WashingtonPost reporter asks one of the olderlooking boys.“Nineteen,” Abou Traore says inJamuary 14, 2020Behind much of the world’s chocolate is thework of thousands of impoverished childrenon West African cocoa farms.a hushed voice. Under Ivory Coast’slabor laws, that would make himlegal. But as he talks, he castsnervous glances at the farmer whois overseeing his work from severalsteps away. When the farmer isdistracted, Abou crouches and withhis finger, writes a different answerin the gray sand: 15.Then, to make sure he is understood,he also flashes 15 with his hands.He says, eventually, that he’s beenworking the cocoa farms in Ivory4‘Too little, too late’The world’s chocolate companieshave missed deadlines to uprootchild labor from their cocoa supplychains in 2005, 2008 and 2010. Nextyear, they face another target dateand, industry officials indicate, theyprobably will miss that, too.As a result, the odds are substantialthat a chocolate bar bought in theUnited States is the product of childlabor.About two-thirds of the world’scocoa supply comes from WestAfrica where, according to a 2015U.S. Labor Department report, morethan 2 million children were engagedin dangerous labor in atives of some of the biggestand best-known brands — Hershey,Mars and Nestlé — could notguarantee that any of their chocolateswere produced without child labor. 2020 THE WASHINGTON POST

Volume 19 Issue 4An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education Program“I’m not going to make thoseclaims,” an executive at one of thelarge chocolate companies said.One reason is that nearly 20 yearsafter pledging to eradicate child labor,chocolate companies still cannotidentify the farms where all theircocoa comes from, let alone whetherchild labor was used in producing it.Mars, maker of M&M’s and MilkyWay, can trace only 24 percent of itscocoa back to farms; Hershey, themaker of Kisses and Reese’s, lessthan half; Nestlé can trace 49 percentof its global cocoa supply to farms.With the growth of the globaleconomy, Americans have becomeaccustomed to reports of worker andenvironmental exploitation in farawayplaces. But in few industries, expertssay, is the evidence of objectionablepractices so clear, the industry’spledges to reform so ambitious andthe breaching of those promises soobvious.Industry promises began in 2001when, under pressure from theU.S. Congress, chiefs of some ofthe biggest chocolate companiessigned a pledge to eradicate “theworst forms of child labor” fromtheir West African cocoa suppliers.It was a project companies agreed tocomplete in four years.To succeed, the companies wouldhave to overcome the powerfuleconomic forces that draw childreninto hard labor in one of the world’spoorest places. And they would haveto develop a certification system toassure consumers that a bag of M&M’sor a Reese’s Peanut Butter Cup didnot originate with the swinging of amachete by a boy like Abou.Jamuary 14, 2020A steady stream of buses from Burkina Faso carry passengers and trafficked children asyoung as 12 to work in cocoa fields in Ivory Coast.“I admit that it is akind of slavery. . Butthey bring them here towork, and it’s the bosswho takes the money.”— Ivory Coast farmerSince then, however, the chocolateindustry also has scaled back itsambitions. While the originalpromise called for the eradicationof child labor in West African cocoafields and set a deadline for 2005,next year’s goal calls only for itsreduction by 70 percent.Timothy S. McCoy, a vice presidentof the World Cocoa Foundation, aWashington-based trade group,said that when the industry signedonto the 2001 agreement, “thereal magnitude of child labor inthe cocoa supply chain and how toaddress the phenomenon were poorly5understood.”Industry officials emphasizedthat, according to the pledgemade to lawmakers, West Africangovernments and labor organizationsalso bear some responsibility for theeradication of child labor.Today, McCoy said, the companies“have made major strides,” includingbuildingschools,supportingagricultural cooperatives andadvising farmers on better productionmethods.In statements, some of the world’sbiggest chocolate companies thatsigned the agreement — Hershey,Mars and Nestlé — said they hadtaken steps to reduce their relianceon child labor.Other companies that were notsignatories, such as Mondelez andGodiva, also have taken such steps,but likewise would not guaranteethat any of their products were freeof child labor.In all, the industry, which collects 2020 THE WASHINGTON POST

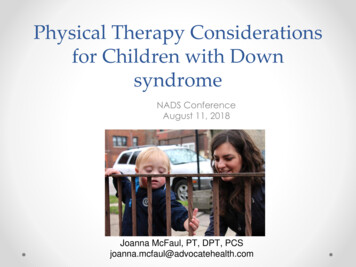

Volume 19 Issue 4An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education ProgramAbou Ouedrago, 15, from Burkina Faso, is like many teen boys on the cocoa farms who sleepin huts out in the woods, spend their days doing hard manual labor and don’t attend school orsee their families.an estimated 103 billion in salesannually, has spent more than 150million over 18 years to address theissue.But when the businesses initiallymade the promise to eradicate childlabor, according to industry insidersand documents, the companieshad little idea of how to do so.Their subsequent efforts have beenstalled by indecision and insufficientfinancial commitment, according toindustry critics.Their most prominent effort —buying cocoa that has been “certified”for ethical business practices bythird-party groups such as Fairtradeand Rainforest Alliance, has beenweakened by a lack of rigorousenforcement of child labor rules.Typically, the third-party inspectorsare required to visit fewer than 10percent of cocoa farms.“The companies have always donejust enough so that if there were anyJamuary 14, 2020media attention, they could say, ‘Heyguys, this is what we’re doing,’ ” saidAntonie Fountain, managing directorof the Voice Network, an umbrellagroup seeking to end child labor inthe cocoa industry. “It’s always beentoo little, too late. It still is.”“We haven’t eradicated child laborbecause no one has been forced to,”Fountain added. “What has been theconsequence . . . for not meeting thegoals? How many fines did they face?How many prison sentences? None.There has been zero consequence.”According to the U.S. LaborDepartment, a majority of the 2million child laborers in the cocoaindustry are living on their parents’farms, doing the type of dangerouswork — swinging machetes, carryingheavy loads, spraying pesticides —that international authorities considerthe “worst forms of child labor.”A smaller number, thosetrafficked from nearby countries,6find themselves in the most diresituations.During a March trip throughIvory Coast’s cocoa-growing areas,journalists from The WashingtonPost spoke with 12 children whosaid they had come, unaccompaniedby parents, from Burkina Faso towork on cocoa farms.While the ages they gave wereconsistent with their appearance,The Post could not verify their birthdates. In much of Burkina Faso, asmany as 40 percent of births gounrecorded in official records, andmany children lack identificationdocuments.The farms were easily visitedbecause they typically lack fences,but people were often reluctant totalk about child labor, which isknown to be illegal and is officiallydiscouraged.Asked about the extent of childmigrants working on Ivorian cocoafarms, the farmer overseeing Abouand the other boys noted the steadystream of buses carrying peoplefrom Burkina Faso into the area.The Post’s reporters also observedthose buses during the March visit.There’s “a lot of them coming,”said the farmer, who asked that hisname not be used because he didn’twant to attract attention from theauthorities. “It’s them who do thework.”The farmer said he was paying theboy’s “gran patron,” the “big boss”who manages the boys, a little lessthan 9 per child for a week of workand who would, in turn, pay each ofthe boys about half of that. 2020 THE WASHINGTON POST

Volume 19 Issue 4An Integrated Curriculum For The Washington Post Newspaper In Education ProgramThe farmer said he considers theboys’ treatment unfair but hired thembecause he needed the help. The lowprice for cocoa makes life difficultfor everyone, he said.“I admit that it is a kind of slavery,”the farmer said. “They are still kidsand they have the right to be educatedtoday. But they bring them here towork, and it’s the boss who takes themoney.”60 percent of the country’s ruralpopulation lacks access to electricity,and, according to UNESCO, theliteracy rate of the Ivory Coastreaches about 44 percent.With such low wages, Ivorianparents often can’t afford the costsof sending their children to school— and they use them on the farminstead.Other laborers come from thesteady stream of child migrants‘It happens on a large scale’who are brought to Ivory Coast byWhat makes the eradication of people other than their parents. Atchild labor such a daunting task is least 16,000 children, and perhapsthat, by most accounts, its roots lie many more, are forced to work onin poverty.West African cocoa farms by peopleThe typical Ivorian cocoa farm is other than their parents, according tosmall — less than 10 acres — and the estimates from a 2018 survey led byfarmer’s annual household income a Tulane University researcher.stands at about 1,900, according“There is evidence that it happens,to research for Fairtrade, one of the and it happens on a large scale,”groups that issues a label that is said Elke de Buhr, an assistantsupposed to ensure ethical business professor and principal investigatormethods. That amount is well below on the study, done in collaborationlevels the World Bank defines as with the Walk Free Foundation, apoverty for a typical family. About group working to end forced labor,‘We are hungry’From the Ivorian economic capitalof Abidjan, the village of Bonon is afive-hour drive along two-lane roadspocked with pond-sized potholes.From the outskirts of the village,footpaths lead into the surroundingforests, where farmers have createdgroves of cocoa trees.Abou Ouedrago uses a machete to chop down a tree on a cocoa farm.Jamua

large chocolate companies said. One reason is that nearly 20 years after pledging to eradicate child labor, chocolate companies still cannot identify the farms where all their cocoa comes from, let alone whether child labor was used in producing it. Mars, maker