Transcription

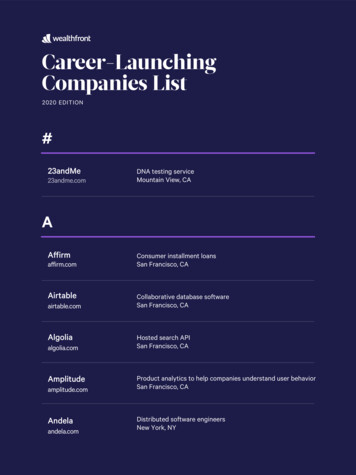

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONS-INAMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGYVol. 7No. 4NSHELLMOUNDS OF THE SAN FRANCISCOBAY REGION.BYN. C. NELSONBERKELEYTHE UNIVERSITY PRESSDECEMBER, 1909

-UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONSDEPARTMENT OF ANTHROPOLOGYThe following publications dealing with archaeological and ethnological subjects issuedumder the direction of the Department of Anthropology -re sent in exchange for the publications of anthropological departments and museums, and for jowrals devoted to generalanthropology or to archaeology and ethnology. They are for sale at the prices stated, whichInclude postage or express charges. Exchanges should be directed to The Exchange Department, IUniversity Library, Berkeley, Oalifornia, U. S. A. All orders and remittances shouldbe adVol. 1.d to the Unlversity Press.Price1. Life and Culture of the Hupa, by Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 1-88;September,19Os .plates 1-30.1903. 1.25plates 1-30. September,2. Hupa Texts, by Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 89-368. March, 1904 . 3.00Index, pp. 369-378.1. The Exploration of the Potter Creek Cave, by William J. Sinclair.AO1-27;Pp. plates 1-14. April, 1904.2. The Langages of the Coast of California South of San Francisco, byA. L. Kroeber. Pp. 29-80, with a map. June, 1904 .60.3. Types of Indian Culture in California, by A. L. Kroeber. Pp. 81-103.251904 .June,4. Basket Designs of the dians of Northwestern California, by A. I.Kroeber. Pp. 105-164; plates 15-21. January, 1905 . . .755. The Yokuts Language of South Central California, by A. L. Kroeber.2.25165-377.Pp. January, 1907.Index, pp. 379-393.The Morphology of the Hupa Language, by Plny Earle Goddard.344pp. . 3.501905June,1. The Erliesttorical Relations between Mexico and Japan, fromoriginal documents presrved in Spain and Japan, by Zelia Nuttall.Pp. 1-47. April 1906 .602. Contribution to the Physical Anthropology of California, based on collections in the Depaxtment of Anthropology of the University ofCalifornia, and in the U. S. National Museum, by Ales HErdlicka.Pp. 49-64, with 5 tables; plates 1-10, and map. June, 1906 .753. The Shoshonean Dialects of California, by A. L. Kroeber. Pp. 65-166.February, 1907 .1.504. Indian Myths from South Central California, by A. L. Kroeber. Pp.167-250. May, 1907 .755. The Washo Language of East Central California and Nevada, by A. L.Krber. Pp. 251-318. September, .1907 . .756. The Religion of the Indians of California, by A. I3. Kroeber. Pp. 319.50356. September, 1907.Index, pp. 357-374.1. The Phonology of the Hupa Language; Part I, The Individual Sounds,.5by Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 1-20, plates 1-8. March, 1907 .3.5.2. Navaho Myths, Prayers and Songs, with Texts and Translations, byWashington Matthews, edited by Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 21-63.September, 1907 .753. Kato Texts, by Pliny Earle Goddard. Pp. 65-238, plate 9. December,2.5019091. The Ethno-Geography of the Pomo and Neighborig Indians, by Samuel Alfred Barrett. Pp. 1-332, maps 1-2. February, 1908 .3.252. The Geography and Dialects of the Miwok Indians, by Samuel AlfredBarrett. Pp. 333-368, map 3.3. On the Evidence of the Occupation of Certain Regions by the MiwokIndians, by A. L.Kroeber. Pp. 369-380. Nos. 2 and 3 in one cover.February, 1908 .50Index, pp. 381-400.1. The Emeryvie Shelimound, by Max Uhle. Pp. 1-106, plates 1-12, with38 text figures. June, 1907 .1.252. Recent Investigations bearing upon the Question of the Occurrence ofNeocene Man in the Auriferous Gravels of California, by WilliamJ. Sinclair. Pp. 107-130, plates 13-14. February, 1908 .353. Pomo Indian Basketry, by S. A. Barrett. Pp. 133-306, plates 15-30,1.75text231 figures. December, 1908.1.--.4. Shellmounds of the San Francisco Bay Region, by N. C. Nelson.309-356,Pp. plates 32-34. December, 1909. ,5012Vol. 2.Vol. 3.Vol. 4.Vol. 5.Vol. 6.Vol. 7.

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PUBLICATIONsINAMERICAN ARCHAEOLOGY AND ETHNOLOGYVOL. 7NO. 4SHELLMOUNDS OF THE SAN FRANCISCOBAY REGION.BYN. C. NELSON.CONTENTS.PAGEIntroduction .---------------310The San Francisco Bay Region as Adapted for Primitive Habitation,311Geographical --312Physiographical and Geologieal Conditions., 312.Climate318Flora and Fauna.319Distribution of the SheJimounds:Present Number .322Appearance, Size and State of Preservation .324Situation with Respeet to Shore-line and Sea-level. .328.Geographical Distribution and its Control330Nature of the Shellmounds:General Status of Shellmound - 332Relation of Shellmounds to other Primitive Structures.------------------------- 333Composition and Internal Structure.335Molluscan Remains .------------- 337Vertebrate Fauna .----------338Culture and History of the Shellmound People:Material Culture . 340Human ------------------------------43344Origin of the People .----------Ageof Settlements.345345The Implied -----------------------------------

310University of California Publications in Am. Arch. and Ethn. [Vol. 7INTRODUCTION.During the season of 1908 the writer completed a somewhatdetailed survey of the evidences of prehistoric man in the SanFrancisco Bay region. The work, which had been under way forsome time, was finished probably none too soon, because theobliterating agencies of nature have been strongly reinforced inthe last four or five decades by the hands of modern man, andthe ultimate destruction of every suggestion of former savagelife seems not far off. Professor John C. Merriam, who directedthe investigation, had himself for some years been collecting dataon the subject, and a comparison of his results with our presentknowledge shows only too plainly how rapidly the monumentsand relics of primitive times are disappearing from the bayshores.The field work connected with the present study representsa review of Professor Merriam's data, with the addition of muchinformation that is new. In the course of three months, thewriter traversed the entire country bordering San Francisco,San Pablo, and Suisun bays; including the tide-water districts ofthe entering streams and also a short strip of the Pacific Coastadjacent to the Golden Gate. The ancient remains discovered orre-examined include shell heaps, earth mounds, and a few minorlocalities that cannot perhaps be termed anything but temporarycamp sites. Of the two most numerous forms, the earth moundsare nearly all located by the entering streams, close to the upperreaches of the tide-waters; and their number could be increasedindefinitely by searching these stream valleys toward theirsources. But as those rather common and widely spread accumulations appear, in many cases, to be of relatively recent origin andpossibly representative of distinct cultures, the present paper isrestricted to a consideration of the shell heaps.' These fairlynumerous deposits, with a few exceptions, are situated close to theopen bay and may, geographically at least, be regarded as adistinct group.I The earth mounds of Central California have been considered brieflyby W. K. Moorehead in his Primitive Implements, p. 258; and by W. H.Holmes, Smithsonian Report, 1900, p. 176.

1909]Nelson.-Shellmounds of the San Francisco Bay Begion.311Thus far only three of the four hundred and twenty-five shellheaps composing the group have been carefully excavated, andthose three were unfortunately on the same side of the bay andnot very far apart.2 Nevertheless, guided by this limited amountof intensive work, the rather more than superficial examinationof all the remaining mounds, supplemented by such sifted information as could be obtained from owners and local residents, mayallow some safe generalizations for the group. The purpose ofthis paper is, therefore, to show by a map the actual location ofall the ancient middens known, to consider the broader factsapparent in the relation of the mound distribution to the localtopography, and, finally, so far as is warranted by availableknowledge, to make some comparisons of the mound group andits culture with that of similar occurrences in other parts of theworld. The paper should be considered only a general or preliminary report which it is hoped may be expanded from time totime as further systematic investigation shall be made possible.The support of the field work has been generously furnishedby Mrs. Phoebe A. Hearst, through the Department of Anthropology. The study as a whole has been pursued as graduate workat the University of California, under the immediate direction ofProfessor Merriam, who has also kindly revised the manuscriptand read the proofs.THE SAN FRANCISCO BAY REGION, AS ADAPTED FORPRIMITIVE HABITATION.With the present tendency of historical research apology isscarcely required for devoting some attention to geography asin part the underlying basis of ethnic conditions. At the sametime, science may doubtless easily overreach itself in the attemptto account all phases of human culture the product merely ofexternal conditions, and the consideration of environment is nottaken up here solely in order to explain archaeological facts, butis made necessary by the established relation between some ofthe shell heaps and certain events in the history of the localtopography. That material conditions do play a fundamental2Bee report on the Emeryville Sheilmound by Dr. Max Uhle in Vol. 7of the present series. Reports on the other mounds are awaiting publication.

312University of California Publications in Am. Arch. and Ethn. [Vol. 7part in human development is not to be questioned. Indeed itwould seem as if environment had so particularly favoredprimitive human life in California that it must in the end beaccepted as one of the chief factors in explaining the presenceof the unusually numerous linguistic stocks, and the fact thatthey managed to exist within these narrow territorial limitswithout losing their identity.GEOGRAPHICAL POSITION.The relation of the region to be considered to the city of SanFrancisco makes its geographical situation a matter of commonknowledge. Definitely fixed, the particular area concerninlg usis included between 1210 56' and 1220 42' west longitude andbetween 370 23' and 38 18' north latitude. In more generalterms, the territory extends from the cities of Napa and Petalumaon the north to San Jose on the south and from the Pacific Coasteastward to the Great Valley, the respective distances being aboutsixty-five, and forty-five miles. The bay itself, with its floodlands, covers approximately 120 square miles and is bounded bymore than 300 miles of shore line.PHYSIOGRAPHICAL AND GEOLOGICAL CONDITIONS.The waters broadly designated by the term San Francisco Bayare confined to a series of connected depressions in the heart of theCoast Range. The mountain system referred to reaches its narrowest limits in this latitude, where its two or three main rangeshave probably always been characterized by a general transversesag, through which the interior basin of the state connected withthe ocean. Since middle Tertiary times, the oscillating movementsof the coast, amounting it seems to over 2,000 feet, have concentrated tidal and drainage currents on this pass until at thepresent time, when the land is relatively high, the enormousdrainage of the interior basin reaches the ocean by way of anirregular line of deep gorges, cut through the three or four lowbarriers that still remain. Descending upon this transversechannel are some six or seven partly united and more or lessdirectly opposable valleys, two from the south and the others

1909]Nelson.-Shellmounds of the San Francisco Bay Region.313from the north; and it is these valleys which, after a partialre-submergenue, have given rise to the present three divisions ofSan Francisco Bay.The outermost and the largest of these divisions, that is SanFrancisco Bay proper, is an elliptical body of water about fortyfive miles long and as much as twelve miles in width. It liesmostly south of the transverse channel and is flanked on the eastby the Mt. Hamilton Range and on the west jointly by the SantaCruz Range and the mountain block north of the inlet, of whichTamalpais is the culminating peak. At the present time itsshores are generally low, marshy and unapproachable, except incertain places about the northern end. Here, especially on thewest side, from San Bruno Point north, several secondary mountain features run out at an angle to the general trend of theshore line, producing an alternating series of inlets and headlands, the latter of which furnish easy approaches to the openbay. The resisting extremities of some of the most prominentof these headlands or peninsulas appear as islands in the bay;and one of these islands, the Potrero Hills, which was once apart of the western shore, has recently, by sedimentation, beenlinked to the opposite shore, while the originally insulatingchannel furnishes the only entrance to the second or centralcompartment of the estuary, namely San Pablo Bay.San Pablo Bay is a roughly circular twelve-mile expanse,actually called Round Bay by the early Spanish explorers. Itis walled in on the west by the same mountain block thatseparates the lower bay from the ocean but on the east by onlya low and narrow strip of the Mt. Hamilton Range. On the northit sends three long tidal arms up the Napa, the Sonoma and thePetaluma valleys-now all choked with silt; while on the southit meets, somewhat abruptly, a broad section of the Mt. HamiltonRange. In other words, the basins of the two lower divisions ofthe estuary do not meet end to end but are roughly parallel andconnect at present by a diagonal channel, the San Pablo Strait.San Pablo Strait, like the Golden Gate below and CarquinezStrait above, appears to be the joint result of subsidence andwave erosion, completed perhaps within recent geological time,but still prior to the oldest records of the shellmound people in

314University of California Publications in Am. Arch. and Ethn. [Vol. 7the region. Probably the older channel, or at any rate the trulystructural connection of the two basins, ran between the PotreroHills and the Mt. Hamilton Range. This passage is now practically obstructed by the joint deltas of the San Pablo and Wildcatcreeks, forming the plain on which the city of Richmond isbuilding. The delta material, containing shell strata in places,is over 500 feet deep; and upon its surface are situated some ofthe largest and oldest of the shell heaps.To the east of the remaining narrow portion of the Mt. HamiltonRange is the third and smallest of the estuary divisions, usuallydistinguished as Suisun Bay. The basin containing this bodyof water is now largely open to the Great Valley, subsidence anderosion having removed or obscured the dividing ridge. Theresult is that Suisun Bay, almost entirely silted up and reducedto tule marsh, appears to be topographically one with theadjacent floodlands of the Sacramento and San Joaquin rivers.These stretches of level floodlands, extending over a large area ofthe lower portion of the Great Valley, are marked by certainnoteworthy features in the form of isolated sand dunes, risinglike islands through the surrounding peat which often attains adepth of forty or fifty feet. We may leave the origin of theseeminences for others to explain, but they are particularly interesting to the archaeologist by reason of the fact that they furnishevidence of having been more or less permanently occupied bythe aborigines. (See pl. 35, fig. 2.)Whether Suisun Bay has been large enough or deep enoughto admit the sea since prehistoric times seems doubtful. Thereare, on the one hand, several old beach marks along its shores,and the lowest of these is not many feet above the present waterlevel; but, on the other hand, the very largest and perhaps theoldest of the shell heaps in the Suisun Bay basin, no. 250, nearConcord, lies approximately at sea level and may therefore havebeen begun at a time when the bay was even smaller than to-day.To be sure, there are other shell heaps in the vicinity of Martinezand above Cordelia that lie on higher ground, but these areinsignificant, in fact almost obliterated, and do not furnish anyreliable tests. In view of these facts it will seem natural enough,therefore, that the remainder of this study should be restricted

1909]Nelson.-Shellmounds of the San Francisco Bay Region.315almost entirely to conditions as they exist on the two lowerdivisions of the estuary.The basins of San Pablo and San Francisco bays may, forour purposes, be considered as a unit and as physiographicallydistinct from the Great Valley, although receiving and transmitting the immense drainage of the latter. Being quite limitedin extent, the watershed belonging to the basin is unable todevelop any large streams. There are some sixty named andrecognized water-courses, besides many more wet-weather gulliesthat descend from the surrounding hills; but of those named onlythe Guadalupe and the Coyote at the southern extremity andthe Napa at the northern, are dignified by the doubtful term"river." Those three, together with the Sonoma and the Petaluma creeks, also on the north, are the only permanently flowingstreams native to the basin. Of the remaining creeks, however,many, such as the Rodeo, the San Pablo, the San Leandro, theSan Lorenzo, and the Alameda on the east side, and at least theSan Francisquito and the San Mateo on the west, would undernormal conditions, flow at all seasons of the year; and would,consequently, be lines of attraction for primitive populations.As it is, the water of nearly all the streams has been divertedin the foothills to satisfy the requirements of modern civilizedlife.In connection with this preliminary statement of the physicalfeatures of the bay region it seems desirable also to call attentionto the influence of the drainage entering or passing through thebay. The processes of erosion and of deposition are both in actionat the same time and often in close proximity; but the wearingdown work is generally confined to the central section of the bayand the building-up process to the extremities. It is along the lineof the great current from Carquinez Strait to the Golden Gate,and at a few other points on the lower bay, as far south as thelatitude of San Mateo, that wave erosion is apparent. Whereverthe projecting headlands reach the open waters high and steepcliffs are usually present. These cliffs have either been workedout since the last subsidence or are holding their own concomitantly with a slow sinking movement, of which it appears that atleast the last eighteen or twenty feet have taken place since man 's

316University of California Publications in Am. Arch. and Ethn. [Vol. 7occupation of the region. Either supposition indicates a congiderable age for some of the shellmounds.The most readily observable progress of erosion is of courseconfined to the recent formations, such as the soft conglomeratesabout Point Pinole and the gravels and clays of the alluvialslope bordering most of the lower bay. Perhaps the most notablewave work within historic times is that on the east shore, betweenOakland and Richmond, where the marsh belt and the detritalslope have been eaten back for a considerable distance. Thewaves have here in all probability also cut away a number of theancient shell heaps.But the tearin

San Francisco Bay. The outermost and the largest of these divisions, that is San Francisco Bayproper, is anelliptical bodyof water about forty-five miles long and as much as twelve miles in width. It lies mostly south of th