Transcription

A Clinical Guide to PsychodynamicPsychotherapyA Clinical Guide to Psychodynamic Psychotherapy serves as an accessible and appliedintroduction to psychodynamic psychotherapy.The book is a resource for psychodynamic psychotherapy that gives helpful andpractical guidelines around a range of patient presentations and clinical dilemmas.It focuses on contemporary issues facing psychodynamic psychotherapy practice,including issues around research, neuroscience, mentalising, working with diversityand difference, brief psychotherapy adaptations and the use of social mediaand technology. The book is underpinned by the psychodynamic competenceframework that is implicit in best psychodynamic practice. The book includes aforeword by Prof. Peter Fonagy that outlines the unique features of psychodynamicpsychotherapy that make it still so relevant to clinical practice today.The book will be beneficial for students, trainees and qualified clinicians inpsychotherapy, psychology, counselling, psychiatry and other allied professions.Deborah Abrahams is a psychoanalytic psychotherapist and chartered clinicalpsychologist with over 25 years of clinical experience, including 15 years in theNHS. She is a dynamic interpersonal therapy (DIT) practitioner, supervisor andtrainer as well as Programme Director of DIT at the Anna Freud Centre. Deborahis a senior member of the British Psychotherapy Foundation and has a privatepsychotherapy practice in North West London offering supervision, psychoanalyticand psychodynamic psychotherapy.Poul Rohleder is a psychoanalytic psychotherapist and chartered clinicalpsychologist, as well as a dynamic interpersonal therapy practitioner. He hasover 15 years’ experience of working in public mental health care systems andin private practice. He is a trustee of the British Psychoanalytic Council andsits on several other professional committees and is currently a senior lecturerat the Department of Psychosocial and Psychoanalytic Studies, University ofEssex, UK.

A Clinical Guide toPsychodynamicPsychotherapyDeborah Abrahams and Poul Rohleder

First published 2021by Routledge2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RNand by Routledge52 Vanderbilt Avenue, New York, NY 10017Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business 2021 Deborah Abrahams and Poul RohlederThe right of Deborah Abrahams and Poul Rohleder to be identified as authorsof this work has been asserted by them in accordance with sections 77 and 78 ofthe Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced orutilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, nowknown or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in anyinformation storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from thepublishers.Trademark notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registeredtrademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intentto infringe.British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication DataA catalogue record for this book is available from the British LibraryLibrary of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication DataA catalog record has been requested for this bookISBN: 978-0-815-35265-5 (hbk)ISBN: 978-0-815-35266-2 (pbk)ISBN: 978-1-351-13858-1 (ebk)Typeset in Baskervilleby Taylor & Francis Books

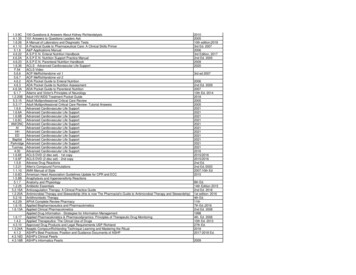

ContentsList of illustrationsAcknowledgementsForeword1 Introductionviiviiiix1PART 1Theory and research112 An overview of psychoanalytic theory133 Efficacy and outcome research43PART 2Competences574 The setting and the analytic frame595 Assessment and formulation886 Anxiety and defences1277 Mentalising1498 Unconscious communications1679 Transference and countertransference18310 Endings207

viContentsPART 3Adaptations and practicalities21911 Brief applications of psychodynamic work22112 Challenging situations and clinical dilemmas23913 Working with difference25614 Technology and social media273Appendix 1:Appendix 2:Appendix 3:Appendix 4:Appendix pecimenterms and conditionsreferral/pre-assessment questionnaireend of therapy reportsocial media contractprivacy notice for website294296299301303305319

he core competences for psychodynamic psychotherapyFreud’s model of the mindA diagrammatic representation of a randomised control trialA diagrammatic representation of Freud’s model of anxiety anddefenceAdapted from Malan’s triangle of conflictTherapist and patient position trianglesAdapted from the Triangle of Person or InsightTwo examples of an Interpersonal Affective Focus for DITUpdated Maslow’s (1943) hierarchy of s of meta-analysis studies on treatment effectivenessDifferent types of defences46130

ForewordWhen I pick up this excellent introduction by Abrahams and Rohleder, Iwonder what the secret ingredient might be that ensures the survival of theideas and practices stated with brilliant clarity in this book. In principle, noscientific theory or clinical practice that is 125 years old has any right to bedescribed as relevant to current practice. So, what has helped psychoanalysis and itsoffspring, psychodynamic psychotherapy, to survive all these years. In this Foreword,I would like to advance a few suggestions about the unique features of the approachwhich are all exceptionally well exemplified by Abrahams and Rohleder’s book.First, the idea that the mind is capable of generating mental disorder, theso-called principle of psychological causation, revolutionised psychiatry in the 19thcentury. The term ‘dynamic’ was used in the late nineteenth century byLeibniz, Herbart, Fechner, and Hughlings-Jackson to contrast with the word‘static’ (Gabbard, 2000). As such, the word served to highlight the distinctionbetween a psychological and a fixed organic neurological impairment modelof mental disorder. Evidently, the approach continues to benefit from theflexibility this bridging of the mind-body divide generates. More recently,‘dynamic’ has come to be contrasted with descriptive phenomenological psychiatry that has focused on categorising mental disorders in circumscribedways, rather than emphasising the way mental processes (thinking, feeling,wishing, believing, desiring) interact to generate problems of subjectiveexperience and behaviour. Psychodynamic Theory, as outlined in the firstchapters of this book, is focused on understanding how we can meaningfullyconceive of mental disorders as specific organisations of an individual's conscious or unconscious beliefs, thoughts and feelings. The rich case studiespresented throughout illuminate the subtleties of this process and how thepsychodynamic clinician, charged with the task of investigating the specificideas and constructions, is able to elegantly explain a person’s suffering.Second, psychodynamic psychotherapy is unique in describing how psychologicalcausation extends to the non-conscious part of the mind. Nagel, Wollheim, Hopkins andother philosophers of the mind (Hopkins, 1992; Nagel, 1959; Wollheim, 1995) haveall pointed to the assumption of unconscious mentalisation as a key discovery withinthe psychoanalytic model. Implicitly or explicitly, psychodynamic models assumethat non-conscious narrative-like experiences, analogous to conscious fantasies,

xForewordprofoundly influence an individual’s behaviour, in particular their capacity to regulate affect and adequately handle their social environment. Whilst no moderncognitive scientists would restrict cognition to consciousness, psychodynamicapproaches are alone in placing non-conscious functioning at the centre of itsdomain of interest. While such interactions go on consciously as well as outside ofawareness, the psychodynamic model has been seen as a model of the mind thatemphasises repudiated wishes and ideas which have been warded off and defensively excluded from conscious experience. The book illustrates how in the pursuitof understanding conscious experiences, we need to refer to mental states aboutwhich the individual is unlikely to be aware. What is more, the psychodynamicapproach provides a roadmap for the likely location of those unconscious concernsand how these can be sensitively explored. It is in this last context that Abrahamsand Rohleder’s book is so valuable. The strategies that the clinician wishing toexplore unconscious content should follow in order to achieve productive therapeutic change are neither simple nor obvious and demand careful committedstudy and opportunity, which the later chapters of the book helpfully present.Third, as described in the initial chapters on the theoretical basis of psychodynamic work, the psychodynamic clinician generally believes that mental disordersare best understood bearing in mind that the mind is organised largely to avoidunpleasure which arises out of feelings and ideas that are incompatible and therefore are in conflict. Psychodynamic approaches consider that given the humancondition, it is axiomatic that wishes, affects and ideas will be, at times, in conflictwith one another. The psychodynamic therapeutic approach sees such incompatibilities as key causes of distress and the lack of a sense of safety. Clinicalexperience shows them to be frequently associated with adverse environmentalconditions. For example, neglect or abuse is likely to aggravate an arguably natural but mild predisposition of the child to relate with mixed feelings to thecaregiver who is perceived as vital to the child’s continuing existence. While slightfragmentation of mental organisation was shown to be ubiquitous by existentialphilosophy (Gadamer, 1975; Heidegger, 1962), psychodynamic techniques oftenaim at identifying perceived inconsistencies, conscious or unconscious, in feelings,beliefs and wishes in relation to oneself and others with the aim of reducing theindividual’s distress. Not only are conflicts thought to cause distress, they are alsoconsidered potentially to undermine the normal development of key psychologicalcapacities that in turn reduce an individual’s competence to resolve incompatibleideas (Freud, 1965). Whilst it may seem obvious that we want to avoid unpleasurewherever we can, psychodynamic theories, and particularly the work of attachment theorists and also Joseph Sandler (2003), explain that it is not simplyunpleasure that we want to avoid; rather, our minds are collectively and probablybiologically organised to maximise a subjective sense of safety and belonging.Fourth, psychodynamic theories are also used in describing the common set ofmental operations that, whilst appearing to distort accurate depictions of realityand mental states, have the capacity to reduce anxiety, distress and displeasure.The term ‘psychic defences’ may risk reification and anthropomorphism (preciselywho is defending whom, and against what?). Notwithstanding this, the concept of

Forewordxiself-serving distortions of mental states relative to an external or internal reality isgenerally accepted and frequently demonstrated experimentally (Lyons-Ruth,2003; Shamir-Essakow, Ungerer, Rapee, and Safier, 2004). Further, individualdifferences in the predisposition to particular strategies may be helpfully examined and codified to groups of individuals and mental disorders in order to provide robust expectations about how a particular person is likely to behave, whatthey are likely to feel, and how they are likely to organise their thoughts (Bond,2004; Lenzenweger, Clarkin, Kernberg, and Foelsch, 2001).Descriptions of defences are invaluable when it comes to understanding theway individuals see the world they are in, sometimes minimising and sometimesexaggerating its dangers. This often leads those individuals to make suboptimaluse of the opportunities they have available to them which can be altered whensuch self-serving distortions are surfaced in consciousness. The psychodynamicapproach is a comprehensive view of human subjectivity, aimed at understandingall aspects of the individual’s relationship with their environment, both external andinternal. Freud’s great discovery that is so often misinterpreted, namely “where idwas, there ego shall be” (S. Freud, 1933, p. 80), points to the power of the conscious mind to alter radically its position with respect to aspects of its own functions,including the capacity to end its own existence. Psychodynamic, as this bookreveals, refers to this extraordinary potential for dynamic self-alteration and selfcorrection – seemingly totally outside the reach of nonhuman species.Fifth, as outlined in the book, psychodynamic psychotherapies are conceived ofin developmental terms. Of course, as the book also makes clear, varying assumptions are made by different psychodynamic approaches concerning normal andanomalous child and adolescent development. Nevertheless, the psychodynamictherapeutic approach is invariably oriented to the developmental aspects of thepatient’s presenting problems. In general, the belief that the past powerfully conditions an individual’s present and future is a key assumption of all psychodynamic ideas. In essence, all psychodynamic psychotherapies are conceived of indevelopmental terms, with varying assumptions concerning normal and abnormalchild and adolescent development (Fonagy, Target, and Gergely, 2006).The sixth powerful general assumption underpinning the psychodynamicapproach, one which runs right through this book like some kind of Brighton rock,is that relationship representations can be assumed to be linked with childhood experiences. Psychodynamic clinicians are by no means alone in considering interpersonalrelationships, in particular the powerful bonds that are created within families, tobe key in the organisation of personality. The specific focus of psychodynamictherapists, however, is the assumption that these intense relationship experiencesare internalised and aggregated across time and come to form a schematic mentalstructure often metaphorically represented as a neural network. Childhood oradolescent experience, sometimes lazily referred to as early experience, is believedto influence interpersonal social expectations. This helps us understand why interpersonal strategies that are less than helpful for individuals may persist many yearsafter their value has lapsed. As a strategy, it is not only obsolete: it is downrightcounter-productive. Interpersonal social expectations influence the relationship with

xiiForewordthe therapist (through the so called transference) in psychodynamic psychotherapybut perhaps also they emerge as parts of other approaches such as developmentalsocial psychology (Mayes, Fonagy, and Target, 2007) or the currently popularexaminative of ACEs (adverse childhood experiences) in adult relationships (Felittiand Anda, 2009) and health (Bellis et al., 2017).The wish to understand this historical way of interacting with others in order tothrow light on the conflicts an individual experiences in the here-and-nowexplains some of the peculiarities in the behaviour of psychodynamic psychotherapists. In order to allow expectations in relation to the therapist to emergeclearly, the psychodynamic psychotherapist is sometimes reticent to show toomuch of their own spontaneous way of acting and may appear so neutral in theface of distress as to attract accusations of being unkind. This is a criticism thatperhaps can be accurately levelled at classical psychodynamic approaches. Itcannot be levelled at this book. Here the therapist emerges as a rounded humanbeing, with the capacity to act spontaneously at least to the point of makingmistakes and saying things they regret. Perhaps the most important concept in thebook focuses on relationship representations. Self–Other relationship representations are considered the organisers of emotion, as feeling states come to characterise particular patterns of Self–Other and interpersonal relating (e.g. sadnessand disappointment at the anticipated loss of a person). The centrality of thisidea, which emerges gradually within psychodynamic theory, helps us understandwhy the Self, a person's identity, cannot be understood except as a function oftheir relationships, how they are seen and their emotional experience of particularrelationships. The combination of its developmental approach and the view thatrelationship experiences accumulate to create a sense of Self as well as a sense ofgeneric Others is the appropriate clinical focus for this book. This so-called objectrelations theory has become the common language for psychodynamic psychotherapy, which has been fragmented historically by numerous individualapproaches to theory and technique.The seventh core feature of the psychodynamic approach that runs throughthis book, perhaps more clearly than most texts of the psychodynamic approach,is the assumption of the complexity of meanings. Whilst there exist key differencesbetween psychodynamic approaches in terms of the specific meanings that areassigned by clinicians to particular pieces of behaviour, the general assumptionpsychodynamic approaches share is that behaviour may be understood in termsof mental states that are not explicit in action or within the awareness of theperson concerned. Symptoms of mental disorders are classically considered ascondensations of wishes in conflict with one another and that exist alongsidedefences against conscious awareness of those wishes. It is striking that differentpsychodynamic orientations find different types or categories of meanings ‘concealed’ behind the same symptomatic behaviours. Some clinicians focus onunexpressed aggression or sexual impulses, others on a fear of not being validated, yet others on anxieties about abandonment and isolation. Within thecontext of this book, it is the effort of seeking further personal meaning thatwould be considered more significant therapeutically, and that is shared by a

Forewordxiiirange of psychodynamic therapeutic approaches (e.g. Holmes, 1998). Elaboratingand clarifying implicit meaning structures, as opposed to giving the patient insightin the terms of any particular meaning structure, appears through these pages asthe essence of psychodynamic psychotherapy.And finally, the unique psychodynamic proposition that past relationshiprepresentations inevitably re-emerge in the course of psychodynamic treatmentsdefines a further concern that preoccupies this book appropriately as it indeedpreoccupies all psychodynamic psychotherapists. Within a psychodynamic framework, there is an extensive literature on both i) the ‘transference’ relationship, inwhich non-conscious relationship expectations, repudiated wishes etc. areassumed to be played out and can be better understood through the sharedexperience of their enactment in a new context, and ii) the ‘real’ relationship,which captures the generic factor referred to above, namely the therapeuticimpact of having a relationship with an interested, understanding and respectfulperson, which may be a new experience for some.However, this goes both ways. Psychodynamic therapists, like everyone else, haveminds that are organised around avoiding unpleasure, are capable of generatingdefensive strategies to avoid challenges; they bring their own histories to the consulting room and their relationship representations dominate the way they formrelationships with their clients. In other words, the non-conscious or indeed defendedagainst dynamically unconscious part of the therapist’s mind comes to psychodynamic treatment with the patient’s capacity to use defences to protect themselvesfrom unconscious conflict. Several things follow from this assumption. Most obviousis the recommendation for psychodynamic psychotherapists to have their own personal therapy in part to be able to share and empathise with the patient’s experiencethat comes to see them but also to deal hopefully with the most problematic aspectsof what they might otherwise bring to the consulting room. Second, is the absoluteneed for supervision at all levels of skill and expertise. Everyone, including the authorof these lines, should be in supervision or at least have the opportunity to discuss theirclinical work with fellow clinicians on a regular basis. Whilst this cannot preventinterference from parts of our mind outside of conscious awareness, it will avert anembedding of patterns of responding to a client that may not be in the client’s orindeed the therapist's best interests.Reflection on experience is a helpful corrective, as identified by most moderntheories of consciousness (Fonagy and Allison, 2016). However, the most important parts of such unconscious reactions are in relation to the therapist’s mind as atool for discovery. An idea which now appropriately permeates psychodynamicpractice is the common-sense notion that the way we react to fellow humanbeings tells us not just something about ourselves but also something about theother person. An emotional reaction of anxiety, boredom or hopelessness may besomething that reflects not only our likely current state of being but also tells ussomething that has been triggered within our own minds which is of immenseimportance in trying to acquire an understanding of the person we are endeavouring to help. The systematic use of countertransference is explained well inthis book alongside many other important psychodynamic techniques.

xivForewordAs an empirical researcher, I genuinely appreciate the unique efforts in this book tointegrate scientific research with descriptions of clinical theory and technique. Theepistemic framework of psychoanalysis, at least in the past, extruded empiricalresearch. Experimental studies pertinent to psychoanalysis and psychodynamic psychotherapy are not simply randomised controlled trials, the strengths and weaknessesof which are well described in Chapter 3. The experimental method integrates anatomical, neurophysiological and genetic observations which are at the cutting-edge ofour modern understanding of mental disorder (e.g. Holmes, 2020). The epistemicreach of psychodynamic theory goes significantly beyond the experimental andencompasses many aspects of psychology, particularly developmental psychology,cognitive science, computational psychiatry, feminist theory, sociology, queer theory,anthropology, pathology, evolutionary psychology, nonlinear dynamics and politicalscience among others; in fact, very many domains of 21st-century thought intersectwith it. Whilst its continued relevance is a puzzle to some, it also underscores the valueof its study. In my view, psychoanalytic theory that underpins psychodynamic psychotherapy is the richest and most sophisticated set of ideas concerning the functioning of the human mind that we currently have available to us. It is a theory that isnested within psychotherapeutic practice. Without the experience of one mind gettingto know another mind in real time interaction (both acting to make the best of theencounter yet both chained by their own history and the profound limitations thatprior experience places upon spontaneous discovery) the theory would be arrested inits development and would not be able to nourish and inspire practitioners strugglingto help those who have come to seek their assistance. Sure, now there are hundreds,probably over a thousand different kinds of psychotherapies. Why should anyonechoose psychodynamic therapy? As a set of techniques, it is unlikely to be moreeffective than others. As an approach to understanding the human mind, it stands onits own. We have ample evidence that psychotherapy can effectively address humansuffering and through it, we may learn about human nature in ways that are perhapseven more important in creating a better world, a world that is adequately understanding and kind to those people whose mental disorder exposes them to distress orwhose actions generate distress in others. So, beyond the appropriate clinical call ofhelping individuals with mental disorders, I would commend to you the study of thisbook as you engage in a profession that will help you better understand others andthus fulfil a wider humanitarian call of creating a more generous and productivehuman environment for one another in this relatively new century where we needinterpersonal understanding more than ever before.Professor Peter Fonagy OBEProfessor of Contemporary Psychoanalysis and Developmental Scienceat University College London (UCL), andCEO of the Anna Freud National Centre for Children and FamiliesJune 2020

ForewordxvReferencesBellis, M. A., Hardcastle, K., Ford, K., Hughes, K., Ashton, K., Quigg, Z., & Butler, N.(2017). Does continuous trusted adult support in childhood impart life-course resilienceagainst adverse childhood experiences - a retrospective study on adult health-harmingbehaviours and mental well-being. BMC Psychiatry, 17(1), 110. doi:10.1186/s12888-0171260-zBond, M. (2004). Empirical studies of defense style: relationships with psychopathology andchange. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 12(5), 263–278.Felitti, V. J., & Anda, R. F. (2009). The relationship of adverse childhood experiences toadult medical disease, psychiatric disorders, and sexual behavior: Implications forhealthcare. In R. A. Lanius, E. Vemetten & C. Pain (eds), The impact of early life trauma onhealth and disease: The hidden epidemic. Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press.Fonagy, P., & Allison, E. (2016). Psychic reality and the nature of consciousness. InternationalJournal of Psychoanalysis, 97(1), 5–24. doi:10.1111/1745-8315.12403Fonagy, P., Target, M., & Gergely, G. (2006). Psychoanalytic perspectives on developmentalpsychopathology. In D. Cicchetti & D. J. Cohen (eds), Developmental psychopathology (2ndedition, vol 1: Theory and methods, pp. 701–749). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.Freud, A. (1965). Normality and pathology in childhood: Assessments of development. Madison, CT:International Universities Press.Freud, S. (1933). New introductory lectures on psychoanalysis. In J. Strachey (ed.), Thestandard edition of the complete psychological works of Sigmund Freud (vol 22, pp. 1–182).London, UK: Hogarth Press, 1964.Gabbard, G. O. (2000). Psychodynamic psychiatry in clinical practice (3rd edition). Arlington,VA: American Psychiatric Publishing.Gadamer, H.-G. (1975). Truth and method. New York: Crossroads.Heidegger, M. (1962). Being and time (J. Macquarrie & E. Robinson, Trans.). New York:HarperCollins (Original work published 1927).Holmes, J. (1998). The changing aims of psychoanalytic psychotherapy: An integrativeperspective. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 79, 227–240.Holmes, J. (2020). The brain has a mind of its own: Attachment, neurobiology, and the new science ofpsychotherapy. London: Confer.Hopkins, J. (1992). Psychoanalysis, interpretation, and science. In J. Hopkins & A. Saville(eds), Psychoanalysis, mind and art: Perspectives on Richard Wollheim (pp. 3–34). Oxford:Blackwell.Lenzenweger, M. F., Clarkin, J. F., Kernberg, O. F., & Foelsch, P. A. (2001). The Inventoryof Personality Organization: Psychometric properties, factorial composition, and criterionrelations with affect, aggressive dyscontrol, psychosis proneness, and self-domains in anonclinical sample. Psychological Assessment, 13(4), 577–591.Lyons-Ruth, K. (2003). Dissociation and the parent-infant dialogue: A longitudinal perspective from attachment research. Journal of the American Psychoanalytic Association, 51(3),883–911. doi:10.1177/00030651030510031501Mayes, L. C., Fonagy, P., & Target, M. (eds) (2007). Developmental science and psychoanalysis.London: Karnac.Nagel, E. (1959). Methodological issues in psychoanalytic theory. In S. Hook (ed.), Psychoanalysis, scientific method and philosophy (pp. 38–56). New York: New York University Press.Sandler, J. (2003). On attachment to internal objects. Psychoanalytic Inquiry, 23(1), 12–26.doi:10.1080/07351692309349024

xviForewordShamir-Essakow, G., Ungerer, J. A., Rapee, R. M., & Safier, R. (2004). Caregivingrepresentations of mothers of behaviorally inhibited and uninhibited preschool children.Developmental Psychology, 40(6), 899–910. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.40.6.899Wollheim, R. (1995). The mind and its depths. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

11 Brief applications ofpsychodynamic workThere is a parody of brief therapy on YouTube, entitled ‘Stop It’ that is comedygold: the actor Bob Newhart plays a psychiatrist consulting with a patient whohas a phobia of being in a confined space. It captures the change in zeitgeist inAmerica from long-term psychoanalysis to brief cognitive-behavioural therapies.Interestingly, therapists from opposing paradigms reference this clip, each claiming it shows their approach in a favourable light. The clip highlights the nature oftherapeutic change and inevitably raises the question about how long therapyshould be. After all, Bob Newhart’s character suggests five minutes is all that isrequired to cure complex difficulties!We typically consider psychoanalysis, psychoanalytic and psychodynamic psychotherapy as intensive treatment that lasts for many months and years. This is theusual, open-ended way of working, particularly in private practice. Longer-termpsychodynamic psychotherapy used to be offered more routinely in public mentalhealth care services, like the NHS. However, such provision has been eroded asdemand for more cost-effective, brief therapy has increased. Long-term treatment inthe NHS often means one year of individual psychodynamic psychotherapy. Included in the psychodynamic competences is the ability to apply the psychodynamicmodel to the patient’s needs, including identifying and implementing the mostappropriate psychodynamic approach. In some settings and with some patients, thismay entail providing time-limited psychodynamic therapy. The psychoanalytic theories outlined Chapter 2 remain the substantive body of work that therapists draw onin time-limited therap

A Clinical Guide to Psychodynamic Psychotherapy A Clinical Guide to Psychodynamic Psychotherapy serves as an accessible and applied introduction to psychodynamic psychotherapy. The book is a resource for psychodynamic psychotherapy that gives helpful and practical guidelines around a range of patient presentations and clinical dilemmas.