Transcription

OCCASIONAL PAPERThe context of REDD in EthiopiaDrivers, agents and institutionsMelaku BekeleYemiru TesfayeZerihun MohammedSolomon ZewdieYibeltal TebikewMaria BrockhausHabtemariam Kassa

OCCASIONAL PAPER 127The context of REDD in EthiopiaDrivers, agents and institutionsMelaku BekeleWondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural ResourcesYemiru TesfayeWondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural ResourcesZerihun MohammedForum for Social Studies (FSS)Solomon ZewdieMEF, REDD SecretariatYibeltal TebikewWondo Genet College of Forestry and natural ResourcesMaria BrockhausCIFORHabtemariam KassaCIFORCenter for International Forestry Research (CIFOR)

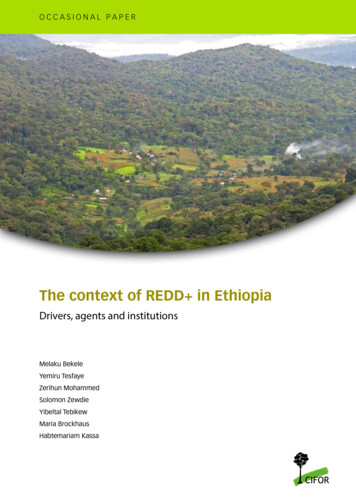

Occasional Paper 127 2015 Center for International Forestry ResearchContent in this publication is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International(CC BY 4.0), http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ISBN 978-602-387-003-5DOI: 10.17528/cifor/005654Bekele M, Tesfaye Y, Mohammed Z, Zewdie S, Tebikew Y, Brockhaus M and Kassa H. 2015. The context of REDD inEthiopia: Drivers, agents and institutions. Occasional Paper 127. Bogor, Indonesia: CIFOR.Photo by Gessese DessieA site between Gore and Tepi, South-West EthiopiaCIFORJl. CIFOR, Situ GedeBogor Barat 16115IndonesiaT 62 (251) 8622-622F 62 (251) 8622-100E cifor@cgiar.orgcifor.orgWe would like to thank all donors who supported this research through their contributions to the CGIAR Fund.For a list of Fund donors please see: https://www.cgiarfund.org/FundDonorsAny views expressed in this publication are those of the authors. They do not necessarily represent the views ofCIFOR, the editors, the authors’ institutions, the financial sponsors or the reviewers.

ContentsAbbreviations and acronymsviAcknowledgmentsviiiExecutive summaryixIntroductionxi1 Analysis of the drivers of deforestation and forest degradation1.1 Current and historical overview of forest resources in Ethiopia1.2 Review of the main drivers of forest cover change1.3 Carbon stocks of the forests of Ethiopia1.4 Mitigation potential1.5 Capacity for monitoring deforestation and forest degradation1161516172 Institutional, environmental and distributional aspects2.1 Putting forest governance in context2.2 Decentralized forest governance and benefit-sharing2.3 Customary rights and international and national legal frameworks2.4 The argument over community rights2.5 Who shall have rights over carbon?2.6 Implications for REDD performance181826293131323 The political economy of deforestation and forest degradation3.1 General background3.2 Overview of Ethiopia’s political systems in the recent past3.3 History of land tenure3.4 National development policies and implications33333334344 The REDD policy environment4.1 Broader climate change policy context4.2 REDD policy actors, events and policy processes4.3 Consultation processes and multi-stakeholder forums4.4 Future REDD policy options and processes44444850535 Implications for the 3Es5.1 National policies, the 3Es and policy options5.2 Assessment of major aspects of REDD and the impact on the 3Es5959636 Conclusions and recommendations697 References72

List of figures and tablesFigures1234567810911121314Land cover types of Ethiopia.Average annual change in the number of holders and area of production of majorcrops from 2006 to 2012.Relative contribution of major crops to the total increase in the number of holdersand area of production.Increase in yield per hectare and area per holder for major crops.Share of major crops in production area increase from 2006 to 2012 in four forestedregions and the country as a whole.Share of major crops in the increase in aggregate production area in forested regions(Oromia, SNNPR, Gambela and Benishangul-Gumuz), non-forest regions and thecountry as a whole.Share of major crops in the increase in production area from 2006 to 2012 forforested zones in Oromia and across the entire Oromia region.Share of major crops in the total production area increase from 2006 to 2012 inforested zones, less forested zones, and the entire Oromia region.Share of major crops in the total production area increase from 2006 to 2012 inforested zones, less forested zones and the entire SNNPR region.Share of major crops in the increase in production area from 2006 to 2012 forforested zones in SNNPR and the entire SNNPR region.Regional share of the total area transferred for commercial agricultural.Uncertified forest owner in his woodlot with his children, Western Arsi zone, 2013.Church forest in northern Ethiopia.PFM areas in imated forest and woodland cover by region for the year 2005, as projectedby the WBISPP and FAO.Estimates of total forest and woody vegetation cover for the years 2000 and 2005according to WBISPP definitions.Total forest and woody vegetation cover estimate after reclassification using FAO’sforest definition.Estimated change in forest cover across different time periods, as forecast bythe WBISPP.Estimated change in woodland cover across different time periods, as forecastby the WBISPP.Estimated change in forest cover across different periods, after reclassification by FAO.Annual deforestation rate estimates of studies in different areas of Ethiopia.The major direct drivers of deforestation in Ethiopia and their level of impact.Share and total area of crop production by region in 2006 and 2012.334445567

The context of REDD in Ethiopia10 The distribution of forest cover among zones inthe Oromia and SNNPR regions.11 Major causes of forest degradation in Ethiopia according to the country’s R-PP.12 Direct drivers of deforestation and forest degradation, their agents, and the levelof threat they impose.13 Carbon stocks of forest vegetation categories.14 Estimates of GHG emissions from agricultural clearing of major forested regions.15 Institutional capacity to monitor deforestation and forest degradation.16 International and regional conventions ratified by Ethiopia.17 The dual path of agricultural development in Ethiopia.18 Investment land under the federal land bank.19 Estimated fuelwood demand and supply.20 CDM projects in Ethiopia.21 Timeline of the development of the R-PP in Ethiopia.22 REDD initiatives in Ethiopia.23 National policies and programs aggravating deforestation in Ethiopia and theirlikely detrimental impact on the 3Es of REDD .24 Policies and programsfor reducing deforestation or increasing sustainabledevelopment in Ethiopia and their likely positive impact on the 3Es of REDD .101414161617223739434752536061 v

Abbreviations and ASDEPPFMREDD R-PPR-PINRTWGSESASFMSLM(P)SNNPRSLMPEffectiveness, efficiency, equityBale Eco-region Sustainable Management ProgramCommunity-based organizationsClean Development MechanismClimate Change Forum-EthiopiaClimate resilient green economy (strategy)Environment Protection AuthorityEthiopia’s Programme of Adaptation to Climate ChangeEthiopian People’s Revolutionary Democratic FrontEnvironmental social management frameworkFood and Agriculture Organization of the United NationsFederal Democratic Republic of EthiopiaForest Carbon Partnership FacilityGross domestic productGreenhouse gasGrowth and Transformation PlanMinistry of AgricultureMinistry of Environment and ForestMinistry of Finance and Economic DevelopmentMonitoring, reporting and verificationNationally appropriate mitigation actionNational adaptation program of actionNongovernmental organizationNon-timber forest productPlan for Accelerated and Sustained Development to Eradicate PovertyParticipatory forest managementReducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradationReadiness preparation proposalReadiness plan idea noteREDD Technical Working GroupSocial environmental strategic assessmentSustainable forest managementSustainable Land Management (Project)Southern Nations Nationalities and Peoples’ RegionSustainable Land Management Program

The context of REDD in s, weaknesses, opportunities and threatsUnited Nations Convention on Biological DiversityUnited Nations Framework Convention on Climate ChangeUnited Nations Convention to Combat DesertificationUnited Nations Development ProgrammeUnited Nations Environment ProgrammeWoody Biomass Inventory and Strategic Planning ProjectGlossary of Ethiopian termsBalabatLocal intermediary between the local people and the State during the imperial periodGebbarTax payer, tribute payerKebeleThe lowest level of government administrationRistHereditary use right of land during the imperial periodWoredaAdministration level equivalent to district vii

AcknowledgmentsThis work is part of the policy component ofCIFOR’s Global Comparative Study (GCS) ofREDD led by Dr. Maria Brockhaus. The studyteam, which consists of university, governmentand civil society staff, would like to express itsgratitude to Dr. Habtemarim Kassa, Dr. AssembeMvondo and Dr. Maria Brockhaus for their inputand guidance.We are grateful to all actors who providedinformation including those from federal andregional government offices and NGOs. This workwould not have been possible without them. Wealso value the time given to the two consultativemeetings we held, one during the launch of thestudy, and the second partway through the project.These meetings were attended by the State Ministerfor Environment and Forest, the Federal REDD Secretariat, regional REDD focal persons andNGO staff, and helped the team to explore thefacts, views and opinions of REDD officialsand focal persons. In addition, we are grateful forthe coordinator’s participation at the 2014 GCSknowledge-sharing event in Ouagadougou. Theevent provided the team with insights into all14 countries included in GCS, and highlightedthe important scope of the study. These insightsallowed us to compare our efforts in Ethiopiawith similar efforts around the globe.We are especially grateful to: Dr. Mulugeta fromFarm Africa; Dr. Yitebitu Moges, Director ofNational REDD Secretariat; and Gideon ShuNeba, Dr. Manuel Boissiere, Dr. Lou Verchotand Dr. Steven Lawry from CIFOR who havereviewed the work in detail and providedvaluable input. We would also like to thankBusha Teshome for his skillful handling of allthe administrative and logistical tasks duringthe three workshops and team gatherings, andCIFOR’s publication team for their editingand layout work. Finally, we thank all theother individuals and organizations that wecannot name individually for all the time andinformation they shared with us.

Executive summaryNotwithstanding the lack of reliable and up-todate countrywide information, the total forestcover of Ethiopia including smallholder/privateand state plantations is estimated to be around13 million ha covering some 11.4% of the totalland area of the country (FAO 2010). The majorforest types identified in the country include: moistmontane forests; dry evergreen montane forests;Acacia-Commiphora woodlands; lowland semievergreen tropical forests; combretum-Terminaliawoodlands and bamboo thickets. In terms of climatechange mitigation potential, scientific evidence,as thoroughly reviewed by Moges et al. (2010),indicates that Ethiopia has the potential to mitigatethe release of 2.76 billion tons of carbon into theatmosphere if it protects and sustainably manages itsforest resources. Despite this substantial potential,the long-standing trend is severe deforestationand degradation (Teketay 2001; Dessie andChristiansson 2008) driven by activities that areclosely linked to the country's political, economicand institutional contexts in the recent past.The major direct drivers of the deforestation anddegradation process are: forest clearance andland-use conversion for smallholder agriculturalexpansion; promotion of large-scale commercialand state development investments in forestfrontiers; illegal extraction and collection of forestproducts (mainly fuelwood collection and charcoalmaking); government-led human settlement inforest areas; forest fires; and increasing developmentof infrastructure and road networks in forestproximities. The dominant actors behind these directdrivers include smallholder farmers and pastoralists;foreign private investors; state-owned enterprisesand government ministries such as the Ministry ofAgriculture and investment agencies, among others.In the context of the Reducing Emissions fromDeforestation and forest Degradation (REDD )Programme, these direct drivers may pose significantchallenges to achieving effective emission reductionsfrom reducing deforestation and degradation.In light of these direct drivers, the challenge forREDD appears to emerge from the fact thatmost of the activities causing the deforestation anddegradation are closely associated with the country'spolitical economy and broader developmentstrategies. Historically, agriculture has been themain stay of Ethiopia's economy accounting for46% of the national gross domestic product and85% of total employment in 2012. For this reason,the current government adopted the AgriculturalDevelopment Led Industrialization (ADLI) as thecountry's main development strategy in 1994. Asa result, a number of subsidiary policies, strategiesand programs were introduced to promote theexpansion, commercialization and export orientationof the agriculture sector. Complementing theADLI strategy, the government developed thePlan for Accelerated and Sustainable Developmentto Eradicate Poverty in 2006 and the ambitiousGrowth and Transformation Plan in 2011. Thelatter aims to transform the country's economy toa middle-income level by 2025 through pursuingfast and broad-based development programs. Themajor strategy to achieve this goal is to attractdirect foreign investment in large-scale commercialagriculture through allocation of extensive lands(mostly in forest areas) and provisioning of taxincentives to private investors. However, theseeconomic-development policies and the approachin which they are being implemented are alsobearing significant costs to the country's land andforest resources.On the other hand, the deforestation processin Ethiopia is also driven by various underlyingcauses including: chronic poverty and the inherentdependence of the vast majority of rural poor onnatural resources; rapid population growth; extensivelegal and institutional gaps including the lack ofstable and equitable forest tenure and property rightarrangements, lack of a clear and standard definitionand classification of forests, and weak forestgovernance and law enforcement capacities; lack of

x Bekele M, Tesfaye Y, Mohammed Z, Zewdie S, Tebikew Y, Brockhaus M and Kassa H.pragmatic stakeholder participation and benefitsharing schemes; and lack of effective cross-sectoralcoordination and vertical integration between lineministries and executive bodies within each ministry.These shortfalls can significantly undermine both theeffectiveness and equitability of REDD actions.Amidst the enormous pressure on Ethiopia'sforests from these drivers and actors, encouragingpolicy measures and practical undertakings arebeing made by the Ethiopian government toharness deforestation and reduce greenhousegas emissions from deforestation and forestdegradation. Evidently, the country has adoptedthe Climate-Resilient Green Economy (CRGE)strategy, which aims to build sustainable economicdevelopment through substantial CO2 emissionreductions in major economic sectors. The forestrysector is identified as one of the four fast-trackimplementation pillars responsible for achieving50% of the national abatement potential. In viewof this, the government has fully embraced REDD as an integral part of the national CRGE strategy.Another important milestone by the governmentis its issuance of the country's first forest policyand proclamation in 2007, with a set of incentivesencouraging private sector and communityparticipation in forestry activities. The country alsoestablished its first Ministry of Environment andForestry in 2013, instituting the national REDD Secretariat under the new ministry. Ethiopia is alsoundertaking several multi-sectoral programs in itsnationally appropriate mitigation actions includingafforestation and reforestation programs, degradedlands rehabilitation and watershed managementprojects, among others, to mitigate the adverseeffects of climate change.The REDD policy process in Ethiopia is thusevolving in a context that it is firmly embeddedin the country's development strategy and inan increasingly enabling political environment,especially at higher levels. In effect, the nationalREDD Secretariat is undertaking variousactivities to pave the way for the developmentand implementation of REDD policies andprograms in Ethiopia. The country has completedthe first phase of its Readiness Preparation Proposal(R-PP) development and is currently workingon phase II of the R-PP, which endeavors todevelop and consolidate the country's capacityand readiness in terms of REDD monitoring,reporting and verification, REDD financing,benefit-sharing schemes, and institutional, legaland policy options. National consultation processesand multi-stakeholder forums at various levelshave been carried out and national REDD management structures are also under-development,among others.Overall, recent policy developments and emergingundertakings by the Ethiopian governmentsignify the building of considerable governmentcommitment to REDD implementation andcarbon emission reductions in Ethiopia. In light ofthe country's ambitious plan for building a climateresilient green economy, the adoption of REDD will also likely reinforce the government's interestin embracing the new financial opportunitiesthat REDD may generate. In sum, analysis ofEthiopia's context for REDD policy developmentand implementation demonstrates the presence of apromising environment for REED in many aspects,yet confronted with serious practical challenges andconstraints that need to be addressed.Achieving lasting results with the implementationof efficient, effective and equitable REDD inEthiopia requires overcoming these challengesthrough enforcing appropriate policy optionsand targeted actions. The first milestone activityto ensure REDD effectiveness is reconciling theapparently contradictory policies and programs– notably policies for agricultural expansion,commercialization and large-scale investment versusinitiatives for natural resources development andenvironmental safeguarding. The counterproductiveimpacts of large-scale commercial investments,infrastructure and road network developments inforest frontiers can be addressed though developinga broader land-use plan and set of legal frameworksthat effectively align these programs with thecountry's forest conservation and development goals.Equally important are improving forest governanceand law enforcement capacities, clarifying andreforming forest tenure and property rightarrangements, formulating equitable benefitsharing and participation mechanisms, enhancinginstitutional capacity and national competence forREDD implementation, and establishing strongcross-sectoral coordination and vertical integration ofministries and agencies involved in the deforestationreduction and forest development agenda.

IntroductionLocated in the horn of Africa, Ethiopia covers atotal area of 1.1 million km2. The country hadan estimated population of 95,045,679 in 2014,with an annual growth rate of 2.58% (Getachew2008). Historically, smallholder-based traditionalagriculture has been the mainstay of Ethiopia'seconomy. However, since 1992 the country’sgovernment has introduced a variety of reformsaimed at improving macroeconomic stability,accelerating economic growth and reducingpoverty. Consequently, Ethiopia has taken adevelopment path that puts the alleviation ofpoverty and enhancement of its people’s livelihoodsas its priority.over half a century of deforestation and forestdegradation driven by several complex factors.According to the government's development plan(Plan for Accelerated and Sustained Developmentto End Poverty, PASDEP), the country envisagesrapid economic development through acceleratedagricultural growth as a stepping stone to thesubsequent development of other economicsectors. And indeed the country has achievedremarkable economic growth, particularly inthe last decade (MoFED 2013). However, thiseconomic growth is at the center of a heateddebate on how the country’s natural resources willconcur with the government plan of achievingrapid economic development through promotingenvironmentally 'insensitive' agricultural expansionand large-scale commercial investment in forestareas. The country’s forest resources provide vitaleconomic benefits and livelihood supports inaddition to critical environmental functions suchas land stabilization, erosion control, regulation ofhydrologic flows and climate change mitigation,among others. But recent data on the statusof Ethiopia’s forest resources, as reported bythe Food and Agriculture Organization of theUnited Nations (FAO) (2010), places Ethiopiaamong those countries with a relatively high rateof deforestation – around 1.0 % per annum.As discussed in Chapter 1, this is the result ofIn view of that, Ethiopia became an officialmember of the UN-REDD Programme in June2011, and so became eligible to access fundingand capacity building support for REDD policydevelopment. In October 2012, the World Bank’sForest Carbon Partnership Facility (FCPF)approved a Readiness Preparation Grant for theEthiopian government to formulate a NationalREDD Strategy and advance its institutionaland technical readiness for REDD . Accordingly,the government is taking steps to set up essentialinstitutional arrangements for managing andcoordinating REDD in the country. Tothat effect, the national REDD Secretariatwas officially established in 2009 under theEnvironmental Protection Authority (EPA) as thebody responsible for the overall implementationof the readiness process outlined in the ReadinessPreparation Proposal (R-PP). In January 2011 thegovernment established the REDD TechnicalWorking Group (RTWG) as one of the membersRecognizant of the enormous pressure of thesefactors, and the growing impact of climatechange on the country's economic growth andthe wellbeing of its people, the government isnow taking measures to reduce deforestation andland-use conversions. Reducing Emissions fromDeforestation and forest Degradation (REDD )1 isone of the schemes that the government has showncommitment to as an alternative mechanism forfinancing its forestry development and enhancingthe country's climate change mitigation potential.1REDD is a mechanism to reduce emissions fromdeforestation and forest degradation plus conserve foreststo enhance forest carbon stocks. It is expected to present anopportunity for developing countries to limit CO2 emissionsthrough payment for actions that prevent forest loss ordegradation.

xii Bekele M, Tesfaye Y, Mohammed Z, Zewdie S, Tebikew Y, Brockhaus M and Kassa H.of the multi-sectoral Climate-Resilient GreenEconomy (CRGE) Technical Committeeresponsible for supervising activities of emissionreduction across the major sectors.The aim of this country profile is to provide acomprehensive assessment of the policy, economicand institutional contexts in Ethiopia withinthe forestry and related sectors in relation toREDD implementation. It provides evidencebased analysis for informing national decisionmakers, practitioners and international actors ofopportunities and challenges in implementing theREDD scheme in Ethiopia. The study is part ofthe Global Comparative Study (GCS) on REDD being undertaken by the Center for InternationalForestry Research (CIFOR).This report is organized into six chapters. The firstchapter describes Ethiopia’s forest resource types,forest coverage and cover changes together with themajor direct and indirect drivers of deforestationand forest degradation. Chapter 2 analyzes nationalpolicy and institutional contexts including aspectsof forest governance and legal frameworks relevantto REDD . Chapter 3 examines the politicaleconomy of deforestation and forest degradation inEthiopia in view of REDD policy developmentand implementation. It explains the interactionsbetween the country's political-economic policydirections and the deforestation and degradationprocess. Chapter 4 describes the REDD policyenvironments and institutional developmentprocess in Ethiopia. Chapter 5 presents an overallevaluation and the implications of Ethiopia'scurrent context for REDD implementation interms of efficiency, effectiveness and equity. Thefinal chapter draws the conclusions of the studyand highlights important policy recommendationsand entry points for successful REDD in Ethiopia.

1Analysis of the drivers ofdeforestation and forestdegradation1.1 Current and historical overview offorest resources in EthiopiaThis chapter describes Ethiopia’s forest resources,and the recent trends and drivers of change in itsforest cover. It focuses on the contextual conditionsthat affect the REDD policy environment of thecountry. Accordingly, discussion of the country’sforest carbon stocks and emission mitigationpotential is also included.1.1.1 Forest types and current status offorest coverDescriptions of forest types are closely related tothe definition of forest used and the classificationscheme applied. However, two or more definitionsand classification schemes are often present andapplied by different users to the same context.As such, the current description of forest types isguided by the definitions and classification schemesbeing applied by the major sources of informationfor this document. These are FAO’s forest resourceassessment (2010) and the Woody BiomassInventory and Strategic Planning Project (WBISPP)(2004), which are the two most commonly usedand influential sources of information for describingEthiopia’s forest resources.The WBISPP produced a comprehensive andreliable assessment of the country’s forest resourcesin the 1990s and a detailed description of Ethiopia'sforest types (Figure 1). FAO later attempted tobuild on and update the WBISPP assessmentby applying its own definitions. The WBISPPdistinguishes between high forests and woodlandsusing the number of storeys in the canopy layerand the maximum height of trees.2 In contrast,FAO’s3main criterion is crown cover. High woodlandand low woodland are further distinguished bythe WBISPP using a tree height threshold of 5 m,whereas trees higher than 5 m are reclassified asforests in FAO’s definition. Of note, the WBISPPforest definition was used as the national forestdefinition in Ethiopia’s R-PP (FDRE 2011c).In terms of major natural forest formations inEthiopia, the WBISPP identifies a bamboo forestand five types of high forests: (i) upland dryevergreen (Juniperus procera), (ii) mixed JuniperPodocarpus upland evergreen, (iii) humid uplandbroadleaved with Podocarpus, (iv) humid uplandbroadleaved with Aningeria dominant and (v)riverine forests. Four types of woodlands are alsoidentified: (i) broadleaved deciduous woodlands, (ii)Acacia woodlands, (iii) lower semi-arid BoswelliaCommiphora-Acacia woodland-shrubland and(iv) lower semi-arid to arid Acacia-Commiphorawoodland-shrubland. These forest classificationsmainly reflect the larger physiographic divisions2The WBISPP defines forest as “land with relativelycontinuous cover of trees, which are evergreen or semideciduous, only being leafless for a short period, and then notsimultaneously for all species. The canopy should preferablyhave more than one story” (WBISPP 2004, 5). It defineswoodland as “a continuous stand of trees with a crown densityof between 20 - 80%. Mature trees are usually single storied,although there may be layered under-stories of immature trees,and of bushes, shrubs and grasses/forbs. Maximum height ofthe canopy is generally not more than 20 meters, althoughemergents may exceed this” (WBISPP 2004, 5).3FAO defines forest as “land spanning more than 0.5hectares with trees higher than 5 meters and a canopy cover ofmore than 10 percent, or trees able to reach these thresholds insitu” (FRA 2010, 5).

2 Bekele M, Tesfaye Y, Mohammed Z, Zewdie S, Tebikew Y, Brockhaus M and Kassa H.Figure 1. Land cover types of Ethiopia.Note: Oromiya Oromia; SNPP Region the Southern Nations, Nationalities and Peoples’ Region (SNNPR); Beni-Shangul Gumuz Benishangul-Gumuz.Source: WBISPP (2005, 15)of highland and lowland forests, which are alsoassociated with differences in important agroecological variables such as elevation, temperatureand rainfall. As a result, they indicate usefulbiophysical and socioeconomic descriptors of eachforest type that can help determine the drivers anddynamics of forest cover changes. For example, thehighlands represent the most densely populatedparts of the country ( 100/km2) whereas thelowlands are predominantly low population densityareas ( 40/km2) (Atlas of Ethiopia 2011). Thehighlands –sitting between 1500 and 2500 masl –also constitute around 43% of the total area of thecountry and contain about 85% of the population,95% of the cultivated land and 80% of the cattlepopulation (World Bank 2004).

The context of REDD in EthiopiaTable 1. Estimated forest and woodland cover by region for the year 2005, as projected by theWBISPP and FAO.RegionWBISPP estimated cover aDire DawaHarariAmharaSomaliAddis AbabaETHIOPIAHigh woodlandFAO estimated cover (ha)Total area (ha)Plantationab9,

3.2 Overview of Ethiopia's political systems in the recent past 33 3.3 History of land tenure 34 3.4 National development policies and implications 34 4 The REDD policy environment 44 4.1 Broader climate change policy context 44 4.2 REDD policy actors, events and policy processes 48 4.3 Consultation processes and multi-stakeholder forums 50 .