Transcription

Drug control policiesin Eastern Europeand Central AsiaThe economic, healthand social impactSPONSORED BY

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impact2Table of contents3Executive summary5About this report8Project overview10Chapter 1: Commissioning in the dark16Chapter 2: Pride and shame21Chapter 3: Unwilling rather than unable– investing in harm reduction30Conclusion34 Appendix I: Country profiles46 Appendix II: Data sources47Appendix III: Data tables49 References The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impact3Executive summaryThe former communist countries of EasternEurope and Central Asia (EECA) are transitioneconomies, attempting to manage risinghealthcare costs whilst reforming their healthsystems.1 EECA is one of the few regions inthe world where the incidence of HumanImmunodeficiency Virus (HIV) is going up.Because of competing needs, public healthinterventions for HIV have been low on policymakers priority lists, with the allocation ofdomestic funds to scaling-up HIV preventionprogrammes falling short of demand.2,3Criminalisation of drug use and incarcerationfor drug-related offences are one of themain influences behind an increase in prisonpopulations in EECA countries.4 Arrestingand putting people who inject drugs (PWID)in prison is both expensive5,6 and associatedwith an increase in HIV infections.7 The fundsallocated to incarcerating PWID massivelyoutweigh those spent on prevention andtreatment for this group. The stigma associatedwith drug use in EECA further hinders theexpansion of HIV prevention programmeswithin mainstream public health.8In parts of Western Europe, evidenceinformed, properly scaled up, community-ledharm reduction services exist, where criminalsanctions for individual use and possessionof drugs are removed and human rights arerespected.9 Such harm reduction approacheshave helped decrease problems with druguse, reduce overcrowding in prisons anddramatically reduce the incidence of HIVin PWID.9 The case for addressing punitivecriminalisation strategies and stigma associatedwith HIV in PWID in EECA is clear, yet progresstowards decriminalisation remains slow.This Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) reportaims to capture the attention of policy-makersin four study countries in the EECA region;Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia tomake the case for the cost effectiveness andhealth gains achieved when the criminalisationof drug use is reduced, harm reduction is scaledup and stigma and discrimination towardsPWID and other vulnerable populations isreduced. To eliminate HIV in PWID this reportarrives at the following four recommendations:A shift in resource allocation. Investing themoney saved from decriminalising drug use andpossession for personal use ( 38m- 773m over20 years) into scaling up antiretroviral therapy(ART) and opioid agonist treatment (OAT) couldeffectively control the current HIV epidemicsamong PWID in the four study countries for noadded cost. This both achieves the Joint UnitedNations Programme on HIV and AIDS (UNAIDS)coverage targets of ART in all settings, increasesthe coverage of OAT and reduces HIV incidencein PWID by 79.4-92.9% over 20 years. As OATis not available in Russia, scaling up needle andsyringe programmes (NSP) is an alternativesolution which would be cheaper than scalingup OAT and ART. It would cost on average 46.5m per year to get 60% coverage of PWIDand avert around 14,000 HIV infections peryear. What is striking about these findingsare the savings and HIV infections avertedfollowing such a simple shift in resources fromcriminalisation to harm reduction approaches,something governments cannot ignore. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impactScaling up harm reduction in prison andcontinuity of care on release. Punishmentshould restrict freedom, not healthcare.Harm reduction needs to be scaled up notonly in the community but also in prisons. Thedata explaining the risk of HIV transmissionin prison is often blurred by underreportingand poor data collection. Special attentionshould be given to PWID when they leaveprison, to ensure they continue to receiveservices, prevent overdose and furtheroffending. Transitional care, which includesthe provision of harm reduction interventionsin prison and sustaining them post releaseis crucial to reducing HIV prevalence inthe long term and should be made partof a national framework that straddleshealth and the criminal justice system.Tackling stigma and discrimination. Stigmaand discriminatory attitudes towards vulnerablepopulations need to be stopped. Stigmareducing workshops which educate the healthand law enforcement sector on HIV preventionis a simple yet scarce solution in EECA.4The importance of counselling, supportingpositive mental health, addressinghomelessness, preventing overdose andproviding access to sexual and reproductivehealth services should be central to theseeducative workshops. Long term solutionsrequire consistent and robust data collectionon violence, discrimination and stigma,alongside actively using tools of influencesuch as shadow and alternative reportingto UN human rights treaty bodies.Urgent law enforcement reform. To stoplaw enforcement officers from committingcorrupt practices, there must be a reform of notonly the police, but also a complete makeoverof drug legislation and healthcare policiessupporting drug users and people living withHIV. Punitive laws against key populationsmust be removed, and vulnerable populationssuch as sex workers, men who have sex withmen, trans people, prisoners and PWID shouldbe protected rather than antagonised bylegal aid and law enforcement institutions. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impact5About this reportThis report describes the methods and main findings fromThe Economist Intelligence Unit research on the criminalisation andhealth of people who inject drugs (PWID) in four Eastern Europe andCentral Asia (EECA) countries: Belarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan andRussia. These countries were selected based on their high burdenof drug use and disproportionate regulations and practices towardsPWID. They are also politically influential countries in the regionalcontext, with Russia setting a standard for drug policies in many ofthe countries in Eastern Europe and Kazakhstan in Central Asia. Thisreport explores the consequences of punitive law enforcement policiesusing a modelling approach which estimates the savings and benefitsfrom scaling up public health interventions for PWID, as opposed tothe current criminalisation approach. The report concludes with keyrecommendations for improving EECA’s harm reduction practices forPWID with a view to reducing the prevalence of HIV. Country profileswhich explore the coverage of harm reduction interventions, attempts toimplement public health policies for PWID, and the current regulationsassociated with drug related crimes are included in the Appendix. Inmost EECA countries, access to reliable prison data and an account ofthe operation of the penitentiary systems are limited. To supplementthe published literature, interviews with experts were conducted,extracts of which are displayed in italics throughout the report.The study was sponsored by Alliance for Public Health (Funded by theGlobal Fund to fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria), which is a leadingnon-governmental organisation aiming to make a significant impact on theepidemics of HIV/AIDS and other serious infectious diseases in the EECAregion and globally. The Economist Intelligence Unit bears sole responsibilityfor the content of this report and the associated executive summary.The views expressed in the report do not necessarily reflect the views ofthe sponsor, or the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria,nor is there any approval or authorisation of this material, expressed orimplied, by the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impact6We would like to thank the following individuals for sharing their insights and experience:Nurali Amalzhonov, President of the CentralAsian People Living with HIV Association,KazakhstanPeter Meylakhs, Associate Professor atSt Petersburg School of Economics andManagement, RussiaAnna Deryabina, Director for Central Asia,ICAP at Columbia UniversityYaroslav Romanchuk, Belarusian economist andpolitician and President of the Mises Centre, BelarusMikhail Golichenko, Previous Russian LawEnforcement Officer, currently a Lawyer andSenior Policy Analyst at the HIV Legal NetworkAnya Sarang, President, The Andrey RylkovFoundation for Health and Social Justice, RussiaNuriana Kartanbaeva, Deputy ExecutiveDirector of the Law programme within theSoros Foundation, KyrgyzstanSherrie Kelly, Infectious Disease Modelling,Burnet Institute, AustraliaRoman Khabarov, Former police officer andhuman rights lawyer in RussiaAlex Knorre, Doctoral student, Department ofCriminology, University of Pennsylvania, USA, andAffiliated Researcher, Institute for the Rule of Law,European University at St Petersburg, RussiaZhannat Kosmukhamedova, Head of the RegionalProgramme Office for Eastern Europe, UnitedNations Office on Drugs and Crime, KazakhstanSergey Soshnikov, Senior Researcher in PublicHealth at the Moscow Institute of Physics andTechnology, RussiaNikita Taranishenko, Former prosecutor,currently human rights lawyer, RussiaDavid Wilson, Currently Global Lead forDecision and Delivery Science, Health andNutrition and Population Global Practice,previously Global AIDS Program Director,The World BankElena Fisenko and Denis Gavarkov, RepublicanScientific and Practical Centre for MedicalTechnologies, Information, Administration andManagement of Health (Principal Recipient ofthe Global Fund Grant), BelarusEliza Kurcevic, Senior Program Officer,Eurasian Harm Reduction Association, Lithuania The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impact7Statistical modelling analyses andassociated data analyses conducted by:Frederick Altice, Section of InfectiousDiseases, Department of Medicine, YaleUniversity School of Medicine, USAJavier Cepeda, Division of Infectious Diseasesand Global Public Health, University ofCalifornia San Diego, USANabila El-Bassel, Section of InfectiousDiseases, Department of Medicine, YaleUniversity School of Medicine, USAAndrea Low, ICAP at Columbia University, MailmanSchool of Public Health, Columbia University, USAJack Stone, Senior Research Associate inInfectious Disease Mathematical Modelling,University of Bristol, UKAssel Terlikbayerva, Section of InfectiousDiseases, Department of Medicine, YaleUniversity School of Medicine, USAKsenia Eritsyan, Sociology Department, HSEUniversity, RussiaPeter Vickerman, Professor of InfectiousDisease Modelling, Bristol Population HealthScience Institute, University of Bristol, UKRobert Heimer, Division of Infectious Diseasesand Global Public Health, University ofCalifornia San Diego, USAZoe Ward, Senior Research Associate inInfectious Disease Mathematical Modelling,University of Bristol, UKTaylor Litz, Division of Infectious Diseases andGlobal Public Health, University of CaliforniaSan Diego, San Diego, USAViktor Ivakin, ICAP at Columbia University,Mailman School of Public Health, ColumbiaUniversity, KazakhstanEIU project team:Chrissy Bishop – Project leadAnelia Boshnakova – Project oversightRob Cook – Project oversight The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impact8Project overviewBackgroundEastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA) is theonly global region where HIV incidence ( 72%)and mortality ( 24%) have increased since2010.10 The Joint United Nations Programmeon HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) sets the global targetsfor reducing the HIV/AIDS epidemics, morecommonly known as the 90-90-90 strategy.This strategy aimed to do the following by 2020: 90% of all people living with HIVwill know their HIV status. 90% of all people with diagnosedHIV infection will receive sustainedantiretroviral therapy. 90% of all people receiving antiretroviraltherapy (ART) will have viral suppression.All EECA countries actively supported theseUNAIDS targets in June 2016, committingto implementing ambitious policies andprogrammes.11 Despite this, in 2019, neitherBelarus, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan or Russia hadmet these targets.12 The previous UNAIDS targetto halve HIV among PWID by 2015 was missedby a huge 80%. Continuing on this trajectory willmean also missing the more ambitious targetto end AIDS (Acquired Immune DeficiencySyndrome) by 2030.13 Despite the severity of theHIV epidemic in EECA, it has not been considereda public health crisis by local governments, whichmay in part be due to political barriers whichmake tackling this issue all the more challenging.The HIV epidemic in this region is largely fuelledby injecting drug use, which accounts for48% of new HIV infections14,15 with PWID alsohaving a high HIV prevalence (7.3-53.4%).16Many PWID are diagnosed late, suggesting thatHIV testing is not delivered at the scale required.17In 2016, the UN General Assembly held a specialsession on the world drug problem, addressingthe need for a person-centred, human rightsapproach to drug use, “saturating areas with highHIV incidence with a combination of tailoredprevention interventions.” Unfortunately, suchsaturation has not occurred in EECA.The region in general is characterised bysuboptimal HIV prevention and treatment,18,19which is perpetuated by limited investments,especially domestic sources of funding.20HIV prevalence is often concentrated amongother high risk groups such as prisoners,7with around 58% of PWID having spenttime in prison at some point in their life.16Although injecting drug use typically reduceswithin prison, high levels of risk exist due tolimited access to sterile injecting equipmentand increased syringe sharing.21,22UNAIDS holds the following risk factorsresponsible for HIV transmission among PWID:151. Criminalisation and punitive laws2. Absent or inadequate prevention services3. Widespread societal stigma4. Lack of investmentDue to slow progress in meeting the UNAIDStargets in the EECA region, demonstratedby a continued increase in HIV infections,the extent and impact of these risk factorsare studied in more detail in this report. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impactObjectivesTo understand the societal and political barriersand the costs involved in scaling up HIVprevention for PWID and treatment targets, theobjectives of this research programme are to:Chapter 1: Explore the burden of HIV in PWID,the provision of harm reduction servicesand the investment environment in EECA.9Chapter 3: Use a modelling approachfor four country settings (Belarus,Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Russia) toestimate the potential benefits in terms ofhealth outcomes and savings of reducingcriminalisation, and investing the savedcosts into increasing OAT and ART.Conclusion: Discuss the implications of thefindings and recommendations for the future.Chapter 2: Explore qualitatively drug lawenforcement and conviction bias in eachcountry, reviewing literature and policy,and conducting interviews with experts. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impact10Chapter 1: Commissioning in the darkThe unknown burden ofpeople who inject drugsAcross Europe in general, there are majordisparities in the provision of HIV care amongsub-regions23, and considerable uncertaintyaround estimating the prevalence of PWID24,making the planning and commissioning ofinterventions challenging. While there is ageneral understanding that HIV prevalenceamong PWID is much greater than the restof the population, usually 28 times higher,15 inpractice, scaling up harm reduction servicesfor PWID is hindered by poor data availability.25Data describing the EECA region often comesfrom studies with varying sample sizes and datacollection methods, making solid conclusionsabout the characteristics and access to publichealth services for PWID difficult, but thereare some common features. All countries showlow coverage of harm reduction interventions,high incarceration rates, and increasingHIV prevalence for PWID.17 Using data froma routinely conducted national sentinelIntegrated Biological Behavioural Survey(IBBS)26 in four study countries, the prevalenceof HIV in PWID (expressed as a proportionof all PWID) is the highest in Russia, followedby Belarus, Kyrgyzstan and Kazakhstanusing data from multiple years (60%, 31%,14% and 8% respectively) (Table 1). As HIV isconcentrated in high risk groups such as PWIDand prisoners, interventions need to span thecommunity and prisons. According to IBBSdata, in Belarus around 76.2% of PWID wereincarcerated at some point, a substantial figure,followed by Kyrgyzstan (46%), Kazakhstan(43.6%) and Russia (34%) (Table 1). Data on thenumber of prisoners is fairly well reported inseveral different places, with Russia havingthe largest prison population, followed byKazakhstan, Belarus and Kyrgyzstan (Table 1). The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

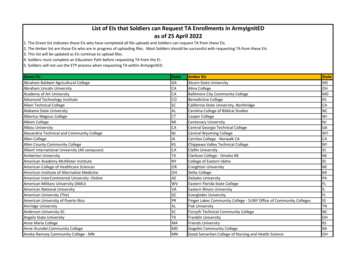

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impact11Table 1: The burden and costs of harm reduction programmesBelarusKazakhstanKyrgyzstanRussiaHIV Prevalence in PWID27-3030.8% (2017)7.9% (2018)14.3% (2016)60% (2017)*Prison population3132,50035,21910,574602,176HIV prevalence in prisons (2015)326%3%11%7%PWID population size16,27-29,3375,000 (2014)120,500 (2016)25,000 (2013)1,881,000 (2017)OAT coverage34-363.7%(community 2019) 1% (2019)4% (2019)0%ART coverage among HIV PWID27-30,36,3740.5% (2018)28.5% (2018)27% (2016)42% (2017)*Recent coverage of NSPprogrammes in community27-2969.4%87.4%55.7%No dataViral suppression among HIV PWID38-4145.8% (2016)54% (2018)89% (2019)81% (2017)*Needle syringes receivedper person per year2427 (16-72)145 (98-216)246 (166-366)2 (1-3)Number of NSP operational sites42341444020Proportion of PWID ever incarcerated27,29,43,4476.2% (2020)43.6% (2018)46% (2016)34% (2012)*Cost of ART per person per year (2018)45,46 302 1,230 363 1,259Cost of OAT per person per year (2018)45,46 550 422 383 441 (scaled fromKazakhstan)Cost of prison per person per year5,47 5,480 (scaledfrom Azerbaijan,2014) 5,952 (scaledfrom Russia costs,2018) 1,259 (2018) 6,641 (2018)Pre-prison one-off cost per person (2010)47 960 (scaled fromRussia costs) 1,161 (scaledfrom Russia costs) 2,008 1,371GDP per capita (2018) 5,419 8,157 1,123 9,586DemographicsCostsAbbreviations: ART - antiretroviral therapy, NSP - needle syringe programmes, OAT - opioid agonist treatment.Note: Data availability in Russia is inconsistent, with estimates coming from different major cities and different sources.St Petersburg had the best data availability for most of the data points required using the IBBS so is used as a proxy forRussia where data for Russia as a whole was not available.*Data for St Petersburg not Russia The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impact12Harm reductionWhat is harm reduction?Harm reduction encompasses a range ofinterventions, programmes and policieswhich aim to reduce the health, social andeconomic harms of drug use to individuals,communities and societies. Providinginterventions and support to PWID ratherthan punishing them, is a public healthapproach which has reduced HIV prevalence,rates of incarceration, overdose deathsand other health related risks in otherparts of Europe.48 Harm reduction typicallyconsists of three main interventions: opioidagonist treatment (OAT), needle syringeprogrammes (NSP) and antiretroviraltherapy (ART). It may also include outreachwork, health promotion and education.49In terms of all people living with HIV, the90-90-90 UNAIDS targets meant thatroughly 81% of all people living with HIVneeded to be on ART treatment, and 73%of all people living with HIV needed to bevirally suppressed for countries to be ableto reach the goal of ending AIDS by 2020.50UNAIDS advises 40% of all PWID need tobe on OAT to reach high coverage levels,a number based on levels of coverageachieved in countries with well-establishedOAT programmes. For NSP programmes,high coverage levels are 60% and above.51Harm reduction interventions haveproduced very beneficial outcomesin different parts of the world.52However, they are more commonly availablein the community and severely lacking inprisons globally, especially in EECA.53,54ART has been shown to dramaticallyreduce the morbidity associated with HIVinfection, and can fully prevent people fromtransmitting HIV.50 OAT is an evidencebased treatment that can reduce overdosemortality,55 reduce the transmission of HIV,and improve HIV treatment outcomes.55-58OAT can also improve the HIV treatmentcascade by recipients having contact witha health professional thus making themmore likely to receive advice and seek HIVtesting and treatment.20,58 This finding hasbeen confirmed in EECA.59,60 There arealso some studies which suggest OAT canreduce levels of crime and prison sentencesamong PWID.(60-74) One study foundthat increasing OAT coverage to 50% ofPWID in prison and retaining them on OATafter release reduced new HIV infectionsin PWID overall by 20% in 15 years.75There are also psychosocial and socialbenefits.76 Taken together these benefitscan indirectly reduce HIV transmission vialowering the number of PWID in prisonand improving the recruitment to, andpreventative benefits of, HIV treatmentsuch as ART.74 Evidence evaluating theeffectiveness of NSPs has shown markeddecreases in HIV transmission by asmuch as 33-42% in some settings.51 The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impactAccess and barriersto services in EECAThere are huge disparities in access to harmreduction services in the EECA region.There are also large differences between accessto harm reduction in the community and prisonsettings, with the latter often having verylittle or no access at all. Moreover, prisons aregenerally a difficult environment to get data,especially on HIV. Similarly to the community,there are no mandatory virus tests in prisonsbut also data collection on drug injectingcan be skewed as it can lead to incriminatingprisoners and disciplinary sanctions, so ofteninjectors prefer to remain undercover.77Access to OAT is only possible in three of thefour study countries, as it is banned in Russia,despite civil society in Russia advocating forharm reduction interventions recommendedby the World Health Organization (WHO).Although possible, access to OAT in Belarus,Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan is low tonegligible.75 Peter Meylakhs, an AssociateProfessor at St Petersburg School of13Economics and Management studies drugtrends and the availability of harm reductionservices in the region. Professor Meylakhsexplains the banning of OAT in Russia is largelydue to an old generation of narcologistswho view its provision to a drug user asswapping one opiate for another, which isa reward, not a treatment. “Even for cancertreatment when patients need strong painkillers such as morphine, there are issues inRussia around supplying opioids for medicaluse, even when the patient is in pain anddying. The methods are very conservative.”Only 3% of prisoners in Kazakhstan wereregistered as opioid dependent according tothe National Narcological Registry,75 despitelocal survey data reporting 43.6% of all PWID in201878 spent time in prison in Kazakhstan at anytime in their lives. In Kyrgyzstan, the NationalNarcology Registry indicates 13.7% of prisoners inKyrgyzstan were opioid dependent in 2015, whichamounted to 1,353 opioid dependent prisoners(taken as a proportion of the prison population in2015). In the same year (2015), only 400 prisonersreceived OAT in Kyrgyzstan,75 suggesting aroundThere are huge barriers to accessingharm reduction services fromlaw enforcement. If you thinkabout the continuum of care,it’s very difficult to access harmreduction services when you havepressure from law enforcementand the risks of being arrestedwhen you try. As a vulnerableperson, you just wouldn’t risk it.Mikhail Golichenko, Lawyer and SeniorPolicy Analyst at the HIV Legal Network The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impact953 opioid dependent prisoners went withoutOAT. Altice et al (2016) estimated 1,066, 205, 1,227people had community access to OAT in Belarus,Kazakhstan and Kyrgyzstan respectively.42,75However, this covers less than 5% of PWIDs ineach country,42,75 falling way below the UNAIDStarget of 40% coverage.51 Coverage has notgreatly improved over time, with more recentdata suggesting that 3.7%, 1% and 4% ofPWID received OAT in Belarus, Kazakhstanand Kyrgyzstan respectively (Table 1).For PWID in the community, NSPs areavailable in all four countries to varyingdegrees. IBBS data reports 69.4%, 87.4% and55.7% of PWID in Belarus, Kazakhstan andKyrgyzstan respectively had contact withNSP programmes.28,78 Contact with theseprogrammes does not mean everyone receivedthe clean needles and syringes they need, withonly Kyrgyzstan meeting the UNAIDS target of200 clean needle syringes per person per year(Table 1).20 In Belarus, 61.3% of PWID inject forsix to nine years on average, with the majorityof PWID injecting on a daily basis.28 BelarusianPWID would need around 364 clean needlesper person per year, but only 27 per personper year were received.24 In Russia, the datapaints a particularly morbid picture. Data onthe number of needle and syringe programmesin Russia recorded 20 operational sites in2018.42 Another source reported only 21-3 needlesyringes were distributed per person per year.24This devastatingly low coverage for such acheap and effective intervention, is making itextremely likely that PWID share needles on aregular basis.17 The only country where NSPsare available in prison is Kyrgyzstan. In Belarus,Kazakhstan and Russia, there is no access toclean needles and syringes in prison at all.75Access to ART is similarly limited in all fourcountries. Only 44% of people with HIV are on14ART in EECA.79 ART coverage for PWID withHIV in the community was the highest in Russiaat 42%, followed by 40.5% in Belarus, 28% inKazakhstan and 27% in Kyrgyzstan (Table 1).Access to HIV services offering ART and otherHIV testing and treatment programmes arelacking and there is poor integration withharm reduction programmes. This makes itdifficult for PWID to access HIV treatmentwhich includes ART.80 ART is technicallyavailable in prisons, with 34% of prisoners inKazakhstan reported to have access in 2015,69.9% in Kyrgyzstan and 5% in Russia (datamissing for Belarus), however there is a generalconsensus that access is negligible and doesnot meet human rights recommendations.75Dr Zhannat Kosmukhamedova is the Head ofthe Regional Programme Office for EasternEurope, within the United Nations Office onDrugs and Crime (UNODC) and explains thatin all these countries (Belarus, Kazakhstan,Kyrgyzstan and Russia) the UNODC are workingon improving many drug policy issues includingaccess to harm reduction, but progress is slow:There are so many barriers toaccessing harm reduction, toOAT and to other HIV preventionservices, many of which aregrounded in stigma, it’s impossibleto speak to one policy change. Wealso have a problem with healthservices. There are huge gaps inunderstanding what the needsof people who use drugs are andstigma exists among health careworkers too. The problem does notsolely lie with law enforcement. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Central AsiaThe economic, health and social impactSergey Soshnikov, who is a Senior Researcherat the Moscow Institute of Physics andTechnology, explains there are still very simplebarriers to understanding the scientific evidencebase around harm reduction which would helpimprove understanding of its effectiveness.“Medical doctors in Russia on the whole don’tspeak any English. Policy-makers in Russiararely speak English. I want to be an advocatefor the evidence base, helping translate it tomedical doctors, rather than continue withall this darkness that surrounds the issue.”Health systems in EECA remain vertical,with a slow pace of health reforms. Betterintegration of care would help with accessingtesting and treatment under the sameroof, without restrictions or stigma. InKazakhstan, improvements are being made.15A lot of health reforms havehappened in Kazakhstan. It used tobe a very vertical system, but duringthe past three years substanceuse specialists have been placedin primary health care clinics.Training has been conducted toenable primary care staff to betterrecognize substance use disordersin terms of how to counsel them.But there is still a long way to go.Anna Deryabina, Director of InternationalCentre for AIDS Care and TreatmentPrograms (ICAP) Central AsiaOverall access to harm reduction is waybelow the expected coverage targets fromUNAIDS51 and is a leading factor to thecontinuing rise in HIV infections in the region. The Economist Intelligence Unit Limited 2021

Drug control policies in Eastern Europe and Ce

the long term and should be made part of a national framework that straddles health and the criminal justice system. Tackling stigma and discrimination. Stigma and discriminatory attitudes towards vulnerable populations need to be stopped. Stigma-reducing workshops which educate the health and law enforcement sector on HIV prevention