Transcription

Kalamullah.Com

AL-MUI:IADDITHAT:the women scholarsin IslambyMOHAMMADAI NADWIInterface Publications

Published byINTERFACE PUBLICATIONSOxford LondonInterface Publications Ltd.Company address:15 Rogers Street2nd floor 145-157 StJohn St.Oxford. OX2 7JSLondon. EC1V 4PYwww. interfacepublications.comCopyright Interface Publications, 2007 (1428 AH)The right of Mohammad Akram Nadwi to be identifiedas the Author of this work has been asserted.All rights reserved. Except for excerpts cited in a review orsimilar published discussion of this publication, no part of itmay be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmittedin any form by any means whatever including electronicwithout prior permission of the copyright owner, obtainable atpermissions@interfacepublications. compaperback: 978-09554545-1-6hardcover: 978-09554545-3-0Typeset in Garamond, 11/12Printed in Turkey by Mega Bas1m Y aym San. ve Tic. A. .\ obans:e me Ma. Kalender Sok. No: 9 3530 Y enibosna.Istanbul.e: export@mega.com.tr

ContentsPREFACE-Acknowledgements, xxiiiList of tables, charts, maps, and illustrationsINTRODUCTION -The impact of the Book andSunnah, 3 -The women's authority established by theQu an and Sunnah, 7 -The women's authority establishedby their own actions, 13xiVlll11THE LEGAL CONDITIONS FOR NARRATINGJ:IADITH -Testimony and narration, 17 (The differencebetween testim01ry and narration, 20) -The lawfulness ofwomen transmitting J:tadith, 22 -The public authority ofJ:tadiths narrated by women, 25 (The adith ofFa(imah bintQ s, 29; Another example: a adith from 'A Jishah, 32)172WOMEN AS SEEKERS AND STUDENTS OFJ:IADITH -The disposition to teach women, 35 (The dutyto teach, 35; Educating the children, 36; Keeping children on theSunnah, 39; Encouraginggirls and women to attend gatherings, 40;The duty to answer the women's questions, 41; The practice of thosewho .followed, 43) -The women's own efforts, 46 (What thewomen asked about, 48; About sf?yness in the w oflearning, 50;Women learningfrom the Companions, 51) -Women'spreserving of the J:tadith, 51 (Memoriifition, 52; Writing, 54;Writing marginal notes, 56; Comparison and correction, 56)353OCCASIONS, TRAVELS, VENUES FOR, ANDKINDS OF, J:IADITH LEARNING -Publicoccasions, 58 (The 4;- tfiJat al-wada', 60)- Privateoccasions, 64- Travelling, 71 (fJajjjournrys, 72) -58

Venues, 76 (Houses, 77; Mosques, 81; Schools, 82)Ways of receiving }:ladith, 84 (Samii' (hearing), 84; al-'Arrj, 85; Ijazah, 86; al-Muniiwalah, 87; al-Mukiitabah,88; al-I'liim, 88; al-Wa.[ryyah, 88; al-Wijiidah, 89;Documentation of the samii' and fjiizah, 89; Queryingijiizahs, 92)- Faj:imah hint Sa'd al-Khayr (?525-600),934THE WOMEN'S TEACHERS -Teachers within thefamily circle, 98 -Teachers of the locality, 102 -Visitingteachers, 103 -Teachers in other towns, 106 -Numberof teachers, 107975THE READING MATTER -The first three centuries,109 -The fourth to the sixth centuries, 110 -From theseventh to the ninth centuries, 114 From later ninth tothirteenth centuries, 119- In the fourteenth century, 121- Kinds of the books they studied, 123 (ai-Muwattii, 123;109al-]awiimic, 124; ai-Sunan, 128; a/-Masiinid, 128; a/-Maciijimand a/-Masi?Jakhiit, 129; ai-Arbaciiniit, 132; ai-Ajzii), 132; a/Musa/saliit, 134) -The reading list of Umm Hani bint Niiral-Din al-Hiiriniyyah (d. 871), 1366WOMEN'S ROLE IN DIFFUSION OF 'THEKNOWLEDGE' -The Companions and the scholarsafter them, 138- Major scholars who narrated fromwomen, 140- Husbands narrating from their wives, 142- Children learning from their mothers, 144 - Childrennarrating from their mothers, 146 - The manners of thewomen scholars, 149 (reaching unpaid; accepting small gijts,154) - The numbers of their students, 155 - How themu/;laddithiit transmitted J:tadith, 164 (Narration of the words,138164; Reading to the teacher, 169; Correspondence, 170; ijiizah,171)- Assemblies for narration and teaching, 176 (Houses,171; Mosques, 179; Schools, 180; Other places, 182)7WOMEN'S J:IADITHS AND NARRATIONSWomen's l;tadiths in the Six Books, 184- The narrators'eloquence, 189- Fiqh dependent on women's J:tadiths,195 (fhe /;ladith of Subqy'ah ai-Aslamryyah, 196; The /;ladith ofBusrah bint rifwiin, 197; The /;ladith ofUmm 'Atiyyah, 198;184

cAJishah's f}adith about the wife ofRifocah aiQura?f, 199)Women's narration of different kinds of[:laclithcompilations, 199 (Jawiimic, 199; Sunan, 203; Masiinid, 206;Maciijim and Masf?yakhiit, 208; Arbaciiniit, 209; Ajza), 210;Musalsaliit, 213; Abundance of their narrations, 214)Collections of the women's narrations, 219 -Higher isniidthrough women teachers, 2278 WOMEN AND J::IADITH CRITIQUE- Evaluation of230narrators, 230 (Tacdil of women narrators, 233; Jar!} of womennarrators, 234)- Evaluation of women's [:lacliths, 235Evaluation of narrators by women, 237 (Women's role intacdil andjarf}, 237; Examples oftacdil andjarf} f?y women, 238)-Women's role in [:laclith critique, 239 (Checking the f}adithagainst the Qur)iin, 240; Checking the f}adith against another,stronger f}adith, 241; Checking the f}adith against a sunnah oftheProphet, 242; Checking the f}adith in the light of its occasion(sabab), 24 3; Checking a f}adith against the difficulty of acting uponit, 244; Checking a f}adith for misconstruction ofits meaning, 244)910OVERVIEW BY PERIOD AND REGION -Firstperiod: 1st-2nd c. ah, 246- Second period: 3rd-5th c. ah,250 - The third period: 6th-9th c. ah, 255 - The fourthperiod: 900-1500 ah - overview by region, 264 (l:IijiiiJ264; Iraq, 265; ai-Shiim (Greater Syria), 266; Egypt, 268; Spainand Morocco, 270; The region ofKhurasan and Transoxania, 271;India, 272)245FIQH AND S4MAL-The fiqh of the women scholars,27 5 (Understanding the Qur)an, 2 75; understanding the f}adith,278; Women jurists, 279; Womengivingfatwas, 281; Debatebetween men and women, 282; Reliance ofthe jurists on the fiqh ofwomen, 283; The women's holding opinions that others disputed,284) -c.Amal, 285273REFERENCES291INDEXES -The Companions and their Successors, 302- The women scholars, 305 -The men scholars, 308 Place names, 316302

list of tables, charts, maps and illustrations*Table 1. Different responses to l:J adith of Fatimah hint Qays, 31Table 2. Famous students of Shuhdah al-Baghdadiyyah, 156-58Chart fo-e. Transmission of abif? al-Bukharito women, 125-27Chart 2. Transmission of Musnad Ibn I-Janbal to women, 130Chart 3. Transmission of Mu'jam al-kabir to women, 130Chart 4. Transmission of ]uz) 'Arafah to women, 211Chart 5. Transmission of]uz) al-An[arito women, 212Chart 6. Transmission of al-Ghcrylan!Jyat to women, 213Chart 7. Transmission ofJuz) Biba to women, 221Map 1.Map 2.Map 3.Map 4.Map 5.Study journeys of Fatimah hint Sacd al-Khayr, 94Islamic world. Spread of mul;addithat 1st-2nd c., 247Islamic world. Spread of mul;addithat 3rd-5th c., 251Islamic world. Spread of mul;addithat 6th-9th c., 256Islamic world. Spread of mul;addithat 1Oth-14th c., 261IllustrationsPhoto. Great Umayyad Mosque, Damascus, xPhoto. al-Jamic al-J:Ianabilah al-Mu{:affari, Damascus, 96Photo. Dar al-Kutub al-Zahiriyyah, Damascus, 137MS copy. Istidca) of Mul:J ammad ibn Qudamah, 91MS copy. Samac of class of Zaynab bint al-Kamal, 159-58MS copy. Jjazah signed by Sitt al-Katabah bint 'Ali al-Tarralf, 171MS copy. Sama' of class of Karimah al-Zubayriyyah, 178MS copy. Sama' of class of Zaynab hint Makki al-J:Iarrani, 181MS copy. 5 amac of class of Karimah al-Zubayriyyah, 183MS copy. Title page of al;tl; al-Bukhari of Sitt al-Wuzara), 200MS copy. ljiizah signed by Sitt al-Wuzara), 201*Maps drawn by Dr. Alexander Kent, FBCart.S., FRGS.Photos from the personal collection of Yahya Michot.MSS photocopies. See text and notes on the page for sources.

Qasim ibn Isma'il ibn 'Ali said: 'We were at the door ofBishr ibn al-I;Iarith, he came [out] to us. We said: 0 AbuNa r, narrate l:J adith to us. He said: Do you pay the zakah[that is due] on l:J adith? I said to him: 0 Abu Na r, is therezakah [that is due] on l:J adith? He said: Yes. When you hearl:J adith or remembrance of God you should apply it.'(see pp. 285-86)

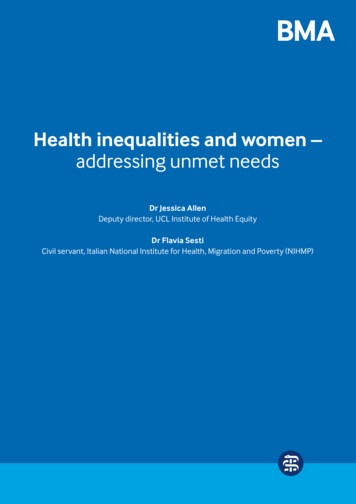

Courtyard of the Great Umayyad Mosque in Damascus, where Umm alDarda' (d. 81) taught ]::ladith andjiqh, and 'A'ishah bint 'Abd al-Hadi(d. 816) was appointed to the post of principal teacher of a i aiBukhiiri.(Photo: Yahya Michot)

PrefaceThis book was conceived as a translation of the muqaddimah toan as yet unpublished biographical dictionary in Arabic of thewomen scholars of l).aclith in Islamic history. However, it wassoon apparent that much of the original needed to be adapted,not simply translated. One reason is that this introduction to thematerial in the Dictionary is not accompanied by that work, andso the material in it needs to be adequately illustrated. Anotherreason is that the expectations of an English readership are somewhat different from an Arabic one. I know that to be so fromquestions put to me after talks I have given on the subject andfrom correspondence following announcement of this book.Those expectations oblige me to say what this book is not, whichis rather an awkward way of explaining what it is.Let me start by stating that this is not an exercise in 'women'sstudies'. I have no specialist knowledge of perspectives associatedwith that discourse. The admission of ignorance should not betaken as indifference to it. Rather, I hope that people skilled in'women's studies' will make proper use of the material presentedhere. That material is, though arranged and organized, a listing, itis, by analogy with a word dictionary, much nearer to 'words'than 'sentences', and far from 'paragraphs' linked into an 'essay'.Much work needs doing on the information before anybodyventures to derive from it value-laden arguments about the past(still less, the future) role of women in Islamic society. Amongthe next tasks are, starting with the easiest:selection and composition from the material: e.g., there are, in theDictionary I have compiled, reams of information on at least a scoreof individual women that could be turned into distinct biographicalstudies. Of course, much labour is entailed: the little sketch of Fatimah bint Sacd al Khayr given here (pp. 93-96 below) needed lookingup half a dozen different books - but at least the Dictionary enablesone to know which books to start with.

XIIAL-MUI:IADDITHATquantitative anafysis: e.g., relative numbers of mupaddithiit in differenttimes and places, and their preferences within the material availablefor study. The overview in Chapter 9 lays out the main blocks of thebig picture but it needs detailing.historical and contextual background: e.g., how particular genres of ]:ladithcompilation developed and were transmitted - some charts providedhere (necessarily scaled down) may indicate directions for such focusedinquiry; how ]:ladith study was affected by political events, administrative arrangements, relations between state and society, and by social andeconomic status; how it was documented; how it was funded (informally, or formally in the waqf deeds of the great madrasas/ colleges).thematicalfy-oriented reflection: e.g., as their names show, many mupaddithiitwere daughters of men bearing the title 'qaQI', 'imam', ']:lafi?' (expert,master), etc. It appears that the men most committed to the educationof women, to respecting and treating them as peers in scholarship,and in the authority that derived from that status, were (as peoplenow use this label) the most 'conservatively' Islamic - their intellectualgenealogy traces to the Sunnah; not to (that other long line in Islamicscholarly effort) Aristotle.My fear is that some readers will not wait for the necessarynext phases of work to be undertaken. Vilification of Islam as amisogynist social order is so intense and pervasive that peopleurgently want assurance that it is not, or was not, or 'need not',be so. Scholarly corrective will not suffice to end that vilification since it is not based upon truth, but upon an aversion toIslam as such, perpetuating itself by seeking, and soon finding,instances of abuse of women (and other negatives like misgovernment, etc.) among Muslim communities. Similar failures in othercommunities are rarely associated with their religious traditionbut explained by local factors. One need only compare the levelof attention given in television documentary to the situation ofwomen in Pakistan with that of women of equivalent socialclass in India to realize that such attention is quite particularlytargeted on Muslims. In part this is because in India (to staywith that example) many middle-class younger women arebeginning to see, and to project, their bodily presence in stylestaken from the West, with some accents from local fashions. Bycontrast, most of their Muslim peers in Pakistan or India are not

PREFACEXIIIdoing the same - like many Muslims elsewhere they are notwilling to subordinate manners derived from their religioustradition to Western tastes. The exasperation with Islamic waysfor showing no consistent tendency to fade out, combined withthe ancient aversion to Islam -it predates the modern Europeanlanguages in which it is expressed - is the principal reason forthe virulence of some feminist critique of it. Muslims, understandably, want their religion defended from that.The feminist agenda, as understood by this outsider to it, hasa practical side and a theoretical side. The former is concernedwith questions of justice for women: equality in pay, access toeducation, employment, political representation, etc. No fairminded person can argue with that. Justice is a virtue; Muslimshave no monopoly either on the definition or practice of virtues.Rather, they are to praise the virtues in whoever has them and,within the boundaries of the lawful, compete therein. It wouldbe hard to improve on the conciseness of this statement on thematter by Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyyah (d. 751), greatest of many1great students of Shaykh al-Islam Ibn Taymiyyah (d. 728):A Shafici said: 'No politics (sryiisa) excepting something that corresponds with the Law (shar !' [.] If in saying 'excepting something thatcorresponds with the Law (shar ' you mean 'which does not run againstwhat the Law has pronounced upon', it is correct. If [on the other hand]you mean [by that] 'No politics except for what the Law has pronounced upon', it is an error [.]. When the signs (amiira) ofjustice appearand its face is radiant, lry whatever means it mcry be, there [you find] the Law ofGod and His religion. God, Praised is He, is too aware, too wise and toojust to restrict the ways of justice, its signs and its marks, to a singlething, to then reject something that may be more evident than those[and] to not judge, when such a thing exists and subsists, that it isobligatory. Through the ways that He has instituted as Law, He hasrather, Praised is He, made it plain that what is aimed at by Him is1I here quote (with italics added) the translation by Yahya MICHOT, inhis discussion of sundry discourses of Ibn Taymiyyah on Muslims undernon-Muslim Rule (2006), 105; the passage is from ai-Turuq al-bukmryyah(ed. S. 'Umran, Cairo, 1423/2002), 17-18.

XIVAL-MUI:IADDITHATthat justice be made to rule among His servants and that people strictlypractise equity. Whatever the wqys ry which justice and equity obtain, thry are apart !if the religion and do not mn against it.The aim of undoing injustices suffered by women (whereverthey are suffered) is acceptable to Muslims. But it is entangled inthe theoretical underpinning of feminist critique, which is notacceptable but which nevertheless invades Muslim minds. I hearit in the form and content of the questions put to me. The formis: if men can do X, why can't women do X? The X could be'pray in a mosque', 'interpret the law', 'issue fatwas', 'lead prayer','travel unaccompanied', 'behave chastely without scarfing thehead', etc. This approach succeeds in embarrassing Muslims byframing each issue as one of equity: if men can X and womencan't, or if women must X but men needn't, it does appear to beunfair. Now, it is not possible here to deal properly with suchquestioning of Islam - as I have said plainly, I am not qualifiedto take on 'women's studies' discourse - but I do owe it to thewomen whose scholarly authority this book celebrates to saybriefly what is necessary to distinguish their perspective. Thesewere not feminists, neither consciously nor unconsciously. Theywere above all else, like the men scholars, believers, and they gotand exercised the same authority by virtue of reasoning withthe same methods from the same sources as the men, and byhaving at the same time, just as the men did, a reputation fortaqwa (wariness of God), righteousness and strong intellect.My concern is that some readers will misunderstand theresemblance, in form and content, between the questions aboveand those found in some of the Prophetic l)adiths cited in thisbook - the women among the Companions say: men are mentioned in the Book, what about us? men are commanded to dothis and that, while we are stuck with the children, what aboutus? Also, readers will find in the book abundant examples ofwomen teaching l)ad1th classes of men and women students inthe principal mosques and colleges (when established, from thesixth century AH on); issuing fatwas; interpreting the Qur'an;challenging the rulings of qa91s; criticizing the rulers; preachingto people to reform their ways - and in all this being approved

PREFACEXVand applauded by their peers among the men. The sheernumber of examples from different periods and regions willestablish that the answer to some of the 'If men can, why can'twomen?' questions is 'Men can and women can too'. That iscorrect, and yet it is not right.It is not right because the approach embedded in the question'if men can, why can't women?' is, from the Islamic perspectiveof the mupaddithdt, misleading in itself. It leads astray by threemain routes. (1) Except as an amusing irony the question is neverput the other way - 'if women can X, why can't men?' Rather, itis taken as given that the traditional domain of women is inferior:running a home, bringing up children are menial chores, unpaidin money or prestige, not a calling. So women should strive totake responsibility in the traditionally male domain of earning aliving and competing for economic and political power, and thedomain of family life - however important it may be - must besqueezed in somewhere somehow between the public domaincommitments of the man and woman. To the extent that a socialorder moves towards that goal, women are freed of economicdependency, of any need to 'wait upon' men, acting as fathers orhusbands (or priests or professors, etc.), telling them what to do.I have worked through much material over a decade to compile biographical accounts of 8,000 mupaddithdt. Not one of them isreported to have considered the domain of family life inferior, orneglected duties therein, or considered being a woman undesirableor inferior to being a man, or considered that, given aptitude andopportunity, she had no duties to the wider society, outside thedomain of family life.(2) The form of the question 'if men can, why can't women?'gives primacy to agenry as the definitive measure of the value ofbeing human. What counts is what one can do, not what one can be;moreover, this approach defines agency in terms of challengingan established order of privilege - here, the privileges men have- so that the emotions and attitudes in play are characterized byresistance, and success is measured in terms of how many can-doitems have been won over from the exclusive ownership of men.Thus, an argument may be contrived along the lines of: these

XVIAL-MUJ:IADDITHATextraordinary women, the mubaddithiit, were - perhaps unconsciously - striving from within (i.e. resisting) against an oppressivesystem, and they achieved as much dignity and liberty of actionas the system could tolerate. (fhe implication is that now wecan do better, go further, etc.)This argument will not hold against the information I havepresented. It will become clear from the first three chapters ofthis book that there is no period when men have certain privileges to speak or think or act, and then women find a way to'invade' the men's ground. Rather, the women and men bothknow,.from the outset q[Islam, what their duties are: women are thereteaching and interpreting the religion from the time that the dutyto do so passed, with the Prophet's death, to the scholars amonghis Companions. Indeed, by the assessment of some later scholars,the Companion most often referred to for fatwas or fiqh wascNishah hint Abi Bakr al-Siddiq. From the Companions itpassed to their Successors. Women are prominent among both,and among the later generations, who continued (or revived)that precedent. There is no evidence of any campaign, overt orcovert, to win rights from men for women.Undue emphasis on agency (being able to do) as a measureof dignity and liberty is an error of more serious import. In thebelievers' perspective, the best of what we do is worship and,especially, prayer. Prayer, in its immediate, outward effects inthe world seems to do nothing. However, the doer of it (andonly the doer) knows how he or she is measured by it - thequality of presence of will, of reflection and repentance, of thecourage to stand alone and quite still on the line between fearand hope before God. Prayer builds (and tests) the stability ofthe qualities that Muslims have treasured most in their scholars,men or women, namely wariness (or 'piety' in relation to God)and righteousness (in relation to other people). It is in thepractice and teaching of these qualities that the mubaddithiit wereengaged. Their personal authority as teachers was no doubt afunction, in part, of sheer technical mastery of the material theywere teaching, but it was also a function of their ability to con-

PREFACEXVIIvey their conviction about it, and its effect on their character,their being.Because of the need to set down a lot of examples of thematerial about the mupaddithiit, I have, with one exception, avoidedlengthy citation of the }:ladiths themselves that they were teaching.The one exception is cAJishah's recollection of the incident of theifk, the slander against her. It is a long story (below, p. 190-95).It ends when her husband, the Prophet, advises her, if she hasdone wrong to repent and God will forgive her. She knows sheis innocent and so turns away from the world that will not vindicate her, saying 'there is no help but in God'. When the Revelation declares her innocent, her mother instructs her to now goto her husband. She flatly refuses: 'By God, I will not go tohim.' Because she is a teenager at the time of this incident, it istempting to read in this disobedience the accents of rebellingadolescence. But in 'Nishah's mature telling of it, it is presentedas the moment when her faith is perfected, when she realizesthat any obedience that is not, first, obedience to God is a burdento the self, an indignity; and every obedience that is for onlyGod is full liberty. She turns away from parents, husband, fromthe Prophet himself: 'By God, I will not go to him. And I willnot praise except God.' The power of agency that comes fromsuch perfected surrender to God (islam) is evident in her conductwhen, having led a battle against Muslims - an action she sincerely(and rightly) repented - and suffered a humiliating rout, she wentdirectly to Basrah, where people flocked to her, not as a politicalfaction, but to learn her }:ladith and her ftqh, her understandingof Islam. The rout took nothing from her personal energy nor from her reputation as a resource for knowledge of thereligion. The all but incredible feats of mental strength andstamina, which are reported of the women scholars of the laterperiods, derive from the same kind and source of agency, thesame achieved freedom of being.(3) The 'If men can, why can't women' approach may alsomislead readers of the material in this book for another reason.It rests on a string of unsafe assumptions: that the differencesgiven in nature (gender is the one we are discussing), if enhanced

XVIIIAL-MUI;IADDITHATby law and custom, must lead to injustices necessari!J; that thoseinjustices should and can be reduced by social, legal and (since wecan do) biological engineering; that such engineering is safebecause the differences as given have little value in themselves,or in their connectedness with anything else.I will not go into the familiar arguments about the negativeeffects of erasing the social expression of gender differences from weakening the boundaries of personal and family life sothat it is spilled into public space for the entertainment of others,to confused sexual behaviours, to impairment of the desire anddrive, perhaps even the capacity, to have children. But the socialexperiment is only just into its second generation. So far there isnot much evidence that women's entry into the high levels ofgovernment, business, etc. has led to any change in either thegoals or the operations of these activities. The women do themjust as well as the men and in just the same way; which suggeststhat their being women is not engaged when at work. But workpatterns and structures take time to alter; it is rather early to bepronouncing on the long-term costs (personal and social) thathave come along with the gains in justice for women. Thosegains matter greatly. Here, I want only to explain that there isanother effort for justice, coming from a different grounding,from different assumptions, and its distinctiveness should not bemissed.As this book shows, women scholars acquired and exercisedthe same authority as men scholars. Both did so within the wellknown Islamic conventions of l;ijab and of avoiding, to theextent practicable, such mixing of men and women as can leadto forbidden relationships. As Muslims understand it, l;ijab iscommanded by God as law-giver, as a social expression andmarking of the gender differences commanded by Him as creator.The practice of l;ijab is thus not dependent upon having reasonsfor it but upon its being His command. However, God as lawgiver commands nothing that He as creator does not also enable,and a part of His enabling obedience is that His commands(like His creation) are intelligible, so that obedience can flow

PREFACEXIXfrom a more willing assent. Hence, Muslims are allowed to ask:what is the point of pijab?Muslims, men and women alike, are required to control theirbehaviour, how they look at, and how they appear to, eachother. But only of women is it required that, in public, they covertheir hair, and wear an over-garment, or clothing that does notcaricature their bodily form: the meaning is - the opposite ofmodem Western conventions - to conceal, not reveal andproject, their bodily presence. The meaning is not that womenshould be absent or invisible, but that they be present andvisible with the power of their bodies switched off. What arethe benefits of this? (1) Most of the time men and women dressto look normal, not to entice one another. But dress normalityfor men - except for the ignominies and anxieties of earlyadolescence - is derived from what other men see as normal;women, even when dressing only for each other, still evaluatetheir look among themselves by its appeal to men. J:Iijab canscreen women from the anxiety, at least when out in public, ofbeing subject to and evaluated by the sexual gaze of men. (2)J:Iyab has an educative function: it teaches chastity to the individual, who learns by it to inhibit the need to be appealing tomen, and to the society in which the need to be self-disciplinedis signalled and facilitated. (3) J:Iijab, publicly and emphatically,marks gender differences; it therefore enables women - alwaysassuming that they are active in the public domain - to projecttheir being women without being sized up as objects of desire.None of that will at all impress those whose landscape isintolerably impoverished by the absence of attractively presentedwomen, or who need the seasoning of flirtation and associatedbehaviours to get through their day. Nor can it impress thosewho do not see pijab except in terms of its symbolizing theoppression of women, who are prevented by it from everenjoying 'the wind in their hair' or 'the sun on their bodies'. (Infact, such enjoyment is not forbidden, only the display of it tomen.) Women who declare that they have chosen to wear pijab aresaid to have internalized their oppression, that is, they are notallowed the dignity of being believed. Yet no-one says of the

XXAL-MUJ:IADDITHATadolescent or younger girls who hurt their own bodies in order tohave (or because they never can have) the right 'look': 'they haveinternalized an oppressive system'. Rather, these negative outcomes are said to be offset by the benefits, overall, to the fashionand entertainment industries. It would be decent to allow Muslimsto say: overall, the benefits of f:J!jiib outweigh any nuisance in it.Anyway, despite pressures, believing men and women willnot, for the sake of Western tastes, abandon the commands ofGod and His Messenger to practice l;ijiib. It is a part of the faith.The great shaykhahs who are the subject of this book, neverdoubted its obligatoriness. Nor is there the least evidence that itinhibited them from teaching men, or learning from men. Clearly,however, there are practical issues involved of how space wasused, how voices were projected so questions could be takenand answered, and how students and teachers could know howthe other had reacted. There is no direct discussion of these practical matters in the sources. One infers from that, that peopleacted in good faith and, in the particular, local conditions, madesuch arrangements as were necessary to convey knowledge ofthe religion to those who came seeking it.Within Islamic tradition, it is generally accepted that oneshould guard oneself

Kalamullah.Com. AL-MUI:IADDITHAT: the women scholars in Islam by MOHAMMADAI NADWI Interface Publications . Published by INTERFACE PUBLICATIONS Oxford London . Women's l;tadiths in the Six Books, 184-The narrators' eloquence, 189-Fiqh dependent on women's J:tadiths,