Transcription

SOLAR POWER ON THE ROOF AND IN THENEIGHBORHOOD:RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CONSUMER PROTECTIONPOLICIESBarbara R. AlexanderConsumer Affairs ConsultantWith the Assistance ofJanee BriesemeisterConsultantMarch 2016

Barbara R. Alexander opened her own consulting practice in March 1996. From 1986-96she was the Director, Consumer Assistance Division, at the Maine Public UtilitiesCommission. Ms. Alexander received her J.D. from the University of Maine School of Law in1976. Her clients include national and local consumer organizations, state public utilitycommissions, and state utility public advocates. Her areas of expertise include consumerprotections to accompany the implementation of retail electric, natural gas, and localtelephone competition, service quality performance standards for electric, natural gas, andtelecommunications providers, low income program design and implementation, consumerprotections associated with pilot and system-wide installation of advanced metering anddynamic pricing programs, analysis of utility customer service programs, and residentialrate design policies.Janee Briesemeister has more than 25 years of experience in consumer advocacy, policydevelopment and advocacy issue campaigns on the state and national levels, and isnationally recognized as a leading consumer advocate on residential utility issues. From2006-2014 Ms. Briesemeister was Senior Legislative Representative in the Department ofState Advocacy and Strategy at AARP. At AARP she was responsible for supporting theorganization’s state offices on consumer-oriented legislative and regulatory advocacy foraffordable utility service, including home energy, telecommunications, water andwastewater. Ms. Briesemeister received the 2011 AARP Lyn Bodiford Award for Excellencein Advocacy, recognition from her colleagues nationwide for leadership of theorganization’s advocacy for affordable home utility service. AARP is the nation’s leadingadvocacy organization for people age 50 and over.The authors gratefully appreciate the assistance and support for this Report from thefollowing: Richard Berkley, Public Utility Law Project of New YorkPaula Carmody, Maryland Office of People’s CounselLinda Conti, Consumer Protection Division, Office of Maine Attorney GeneralTanya McCloskey, Pennsylvania Office of Consumer AdvocateMark Toney and Marcel Hawiger, The Utility Reform Network (TURN), CaliforniaIn addition, the authors thank Carol Biedrzycki of Texas Ratepayers Organization to SaveEnergy (ROSE) in Texas for her assistance.However, the authors remain solely responsible for the content and recommendations ofthis Report.2

TABLE OF CONTENTSINTRODUCTION AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 4CHAPTER I: THE MARKET FOR RESIDENTIAL SOLAR IS GROWING, FUELED BY NEW FINANCINGOPTIONS . 7CHAPTER II: IT IS DIFFICULT TO SHOP AND COMPARE COSTS FOR ROOFTOP SOLAR AND THEPROJECTED IMPACTS ON A RESIDENTIAL CUSTOMER ELECTRIC BILL . 12A. SOLAR COMPANY WEBSITES OFTEN MAKE GENERIC STATEMENTS AND DO NOT EXPLAINMANY DETAILS OF THE PROPOSED TRANSACTION . 12B. IT IS DIFFICULT FOR CUSTOMERS TO DETERMINE THEIR OVERALL SAVINGS FROMINVESTING IN SOLAR PRIOR TO ENTERING INTO A PURCHASE, LOAN, LEASE OR PPA . 15C. FEDERAL AND STATE INCENTIVES IMPACT CUSTOMER PAYMENTS AND SAVINGS FORSOLAR . 17CHAPTER III: THE CASE FOR ADOPTING CONSUMER PROTECTIONS FOR SOLAR POWERTRANSACTIONS . 19A. CUSTOMER COMPLAINTS AND REVIEWS . 19B. STATE ATTORNEY GENERAL ENFORCEMENT ACTIONS AND CIVIL SUITS . 20C. LEGISLATIVE INITIATIVES . 21D. STATE AND FEDERAL GUIDANCE ON ENVIRONMENTAL CLAIMS. 23E. PROPOSALS FOR INDUSTRY SELF-REGULATION ARE INSUFFICIENT FOR CONSUMERPROTECTION . 24CHAPTER IV: RECOMMENDATIONS FOR CONSUMER PROTECTION POLICIES AND MANDATES FORRESIDENTIAL SOLAR TRANSACTIONS . 26A. REGISTRATION AND LICENSING . 26B. DISCLOSURES . 28C. CONTRACT TERMS . 31D. SALES AND MARKETING CONDUCT . 35E. ENFORCEMENT AND PENALTIES; CUSTOMER COMPLAINTS . 36CHAPTER V: COMMUNITY SOLAR PROJECTS: ADDITIONAL CONSUMER PROTECTIONS . 37APPENDIX A: SUMMARY OF STATE PROPOSED LEGISLATION (2014-2015) . 43APPENDIX B: CRITIQUE OF THE SEIA BUSINESS CODE FOR SOLAR TRANSACTIONS AS ASUBSTITUTE FOR STATE REGULATORY OVERSIGHT AND STANDARDS . 46APPENDIX C: CONSUMER EDUCATIONAL MATERIALS . 51ENDNOTES. 523

INTRODUCTION AND EXECUTIVE SUMMARYThe purpose of this Report is to address the need for essential consumer protectionpolicies to govern the burgeoning markets for residential rooftop solar systems andcommunity solar projects.The U.S. residential solar market has experienced explosive growth in the last fiveyears, fueled by lower costs, state and federal incentives, and new financing options,including leases and purchased power agreements, also known as third-party ownership.Community solar, where a consumer subscribes to shares in a solar system that is locatedin a neighborhood or community, is a relatively new and growing option.Consumers may be interested in solar power to help the environment, or simply tosave money on their electric bills. Whatever the motivation, it is not easy to comparisonshop for solar power. Consumers will be faced with comparing the costs of outrightpurchase, a purchase power agreement, a lease, or a loan. Whether purchased or leased,the consumer is making a long-term financial commitment with the expectation thatsavings on utility bills will offset the monthly cost of the system. Achieving these savings inreality is dependent on a variety of factors—including contract terms, federal, state, andlocal subsidies, the estimated increase in the customer’s cost of electricity, and theperformance of the solar panels themselves. It would be easy for a consumer to be misledinto a purchase based on exaggerated assumptions about future savings. Indeed, consumercomplaints have prompted states to take action in the courts, and propose consumerprotections to address actual and potential abuses and misconceptions.This Report describes the marketing, sales practices, disclosures, and contractualterms concerning the costs and benefits of installing rooftop solar systems or participatingin community solar systems. While several existing laws and regulations may be applicableto residential rooftop solar installations, those policies are not specifically targeted to solarinstallations and the associated financial transactions. This Report recommends that solarenergy providers that engage in sales, leases and purchase power agreements, as well asthose offering community solar projects, should be subject to oversight by a state agencyand be required to provide consumers key disclosures, fair contract terms, and be subjectto penalties for violating state laws and regulations.This Report will not address issues governed by homeconstruction codes and oversight, nor the disclosures andoversight associated with loans directly provided by financialinstitutions. This Report should be viewed as complementary tothe oversight by state Attorneys General under a state’s UnfairTrade Practice laws, the Federal Trade Commission under thecomparable Federal Unfair Trade Practice law, and any state andfederal regulations that specifically address Door to Door Salesand Telemarketing Sales activities. These existing consumerprotection policies, while valuable, are not comprehensive and donot address the specific types of transactions and associatedunique features for rooftop solar systems or community solarsystems.The preferred approach foroversight of solar energy providersoffering residential rooftop orcommunity solar projects should beuniform and comprehensive jurisdictionby the state utility commission, or otherequivalent state agency. Solar energybusinesses are marketing to residentialelectric utility customers for a productthat is inexorably linked not only to the4

customer’s monthly electric bill (and the purchase of which might even appear on theutility’s electric bill under some proposals), but is also located in the utility’s distributiongrid. To some extent, utility commissions already regulate solar power with their detailedpricing decisions on net metering and value of solar tariffs that are crucial to the marketingclaims related to lowering a household electric bill. Often state policy requires the statepublic utility commission to promote solar power specifically as part of the effort toachieve renewable energy and carbon emission reduction goals. Commissions thentypically require utilities to make investments to accommodate the integration ofdistributed generation and solar energy facilities, whether through individual customerrooftop installation or local community solar programs. Thus, it follows that state utilitycommissions are the most logical focus to oversee retail solar sales, and suggestions tolimit the jurisdiction of utility regulators to only a few types of solar transactions wouldresult in likely confusion by consumers as to their rights and remedies when shopping forsolar systems. However, states may decide that a different state agency should exercisethis oversight and jurisdiction and our recommendations would accommodate analternative approach.This Report proposes consumer protections specific to solar lease and saletransactions, with disclosures and contractual provisions that flow from the long standingconsumer protection policies that have governed retail sales of products and services toresidential customers.The key recommendations set forth in Chapter IV include the following policies:Registration or Licensing; State Agency Authority: Consumers protections are not effectiveunless a governmental agency has the authority to investigate complaints and take actionagainst bad actors, and such enforcement cannot occur without registration or licensing.Regulators should know how to contact authorized representatives, investigate thebackground of a business, and take action against a provider for violations of state laws andregulations.Disclosures: A Customer Template: This Model would not regulate the financial contents ofthe solar provider’s offer, but would require all solar providers marketing to residentialcustomers to use the same terms and definitions and make their offers in a manner thatallows a comparison of impacts on the customer’s electricity bills and obligations under theapplicable financial arrangement.Contract Provisions: Standardizing contract terms and disclosures does not in any wayregulate or limit the price charged for a solar lease, purchase power agreement or sale.However, certain contract terms should be specifically addressed and, in some cases,mandated or prohibited to prevent unfair dealing and one-sided bargains about fine printterms and conditions.Sales and Marketing Conduct: Consumer protection regulation applicable to retail solarproviders should explicitly prohibit misleading and deceptive sales and marketing5

statements and reference the state’s specific unfair trade practice or general consumerprotection law. A seller cannot misrepresent the nature of the formal agreement or usestatements that are directly contradicted by the formal agreement or contract.Terms at the Sale of a property: There have been complaints about third party financingarrangements including a provision giving the solar provider (the owner of the solar panelsin several types of financial arrangements) the right to approve a new home owner beforethe lease could be transferred to the new owner. Several states have addressed thissituation in their proposed legislation, and the rights and obligations at the time of the saleof property are a key disclosure in the recently enacted Arizona law.Enforcement and Penalties; Customer Complaints: The proposed consumer protectionscannot be effective unless those regulations can be enforced and violators penalized.Enforcement requires that an agency have the authority and necessary resources toinvestigate complaints, access the solar provider’s records demonstrating compliance withthe underlying consumer protection and contract requirements, take actions to revokelicenses or registration, and assess fines or penalties to ensure customers are protected.6

CHAPTER I: THE MARKET FOR RESIDENTIAL SOLAR IS GROWING,FUELED BY NEW FINANCING OPTIONSThe U.S. residential solar market has experienced explosive growth in the last fiveyears. This growth has benefited from several factors. First, the cost of solar power panelshas dropped significantly in recent years.1 Second, federal and state subsidies andincentives have further lowered the net cost to consumers. Finally, the solar industry hasdeveloped new financing methods, including loans, leases and purchased poweragreements, that lower the initial cost to residential customers. The result is that financialinvestors have supported the development of solar power companies, their marketing andsales activities have expanded to many states, and new industry entrants have proliferated.When a customer installs solar panels on their roof, they have installed a tinygenerating plant for electricity. The allure of solar to many customers is not its initial cost,which is significant, but the potential for the customer to generate electricity and reducethe amount of electricity purchased from the local utility and contribute to the “greener”generation of electricity. But, that is only part of the customer benefits. The customer maygenerate more electricity under certain times of the day or under certain weatherconditions than the customer needs and so this “excess” electricity is flowed back into theutility’s distribution system and the customer is paid for generating this excess electricity.From the solar customer’s perspective, the issue is whether the reduced usage and thepayments for excess generation (the resulting monthly electric bill) offset the upfront andmonthly costs of the solar installation, whether purchased outright, through a loan, orleased from the solar company.The method or manner in which the customer is paid for generating excesselectricity by the utility is referred to as “net metering” or the “value of solar.” Themethodology for calculating the value and the payments to the customer for this excesselectricity is highly controversial mainly because the utility is allowed to recover the costsof the bill impacts associated with solar (i.e., reduced usage and payments for excessgeneration) from other customers. Utility rates are regulated by the state public utilitycommission and a utility is allowed to set rates that recover its approved revenuerequirement. As a result, there is a growing concern about the shift in costs to support theelectricity system from solar customers to non-solar customers.2 This Report does notaddress this issue, but rather focuses on the need for consumer protection policies andprograms that address the marketing, sales, and contract terms associated with residentialsolar projects—whether installed on the customer’s roof or as part of a community solarproject financed by a group of customers. Indeed, several states are reconsidering their netmetering polices, and significant changes have recently been adopted by Nevada andHawaii. Appropriate disclosures and accurate savings calculations are all the moreimportant for consumers in this changing marketplace.The solar industry consists of three distinct markets: individual customer rooftopsolar; utility-owned solar power generating facilities; and community solar. Rooftop solaris, as the name implies, typically installed on an individual customer’s roof. Utility-owned7

solar power facilities are larger arrays of solar panels that are installed on the ground andform part of the utility’s generation mix for all its customers and the prudent costs for thesefacilities are included in rates paid by all customers. Community solar is usually installedon the ground and financed by a private or publicly owned organization to serve a group ofcustomers in a neighborhood or defined geographic area. Solar power is a form of“distributed generation” because it is a form of generation of electricity that can be locatedthroughout the distribution system of an electric utility, very different from the moretraditional large power plants that have historically been used to produce electricity. ThisReport does not use the term “distributed generation” because that is a generic term thatcan include generation resources other than solar. For ease of reference this Report usesthe term “solar power” or “solar energy facilities or systems.”Through the end of 2014, more than 600,000 homes and businesses had installedon-site solar, typically on the roof. The residential market grew by more than 50% annuallyin 2012, 2013, and 2014—a trend that some experts predict will continue for 2015 and2016. These systems generate approximately one-third of the total U.S. solar electricityproduction. The market for residential solar is expanding rapidly across the country.Twenty-one states have now added more than 100 MW of solar PV. Yet the top five statesstill account for nearly three-fourths of cumulative U.S. PV installations, with approximatelyhalf of all residential solar installations in California.3 Preliminary 2015 data confirms thesignificant growth in residential solar installations by 66% compared to 2014 andconstitutes 29% of the entire U.S. solar market. Actual activity remains concentrated in tenstates.4Homeowners can contract with a solar energy company to have a solar systeminstalled on their rooftop (or elsewhere on their property). The homeowner may beoffered a loan or third party ownership arrangement to lower the initial investment costsof the system. Although rare just a few years ago, 72 percent of residential solar systemsinstalled in 2014 were financed through a third-party ownership model (i.e., solar leasingor a third-party power purchase agreement (PPA)) 5. While third-party ownership hasbeen on the rise in the residential market, some analysts predict its growth will slow downand that financing trends may shift back to loan products.6Depending on the third party ownership agreement, the solar company will often beresponsible for financing, permitting, designing, installing, and maintaining the solarsystem. Under the typical third party ownership agreement, the homeowner also assignsany tax incentives, rebates or other incentives to the solar provider (the third-partyowner). The assumption is that these benefits have been factored into the contract terms.The following financial arrangements can be offered to a customer interested inrooftop solar,7 but not all solar companies offer all these options and several of theseoptions are not available in all States due to state laws that may impact the ability of solarproviders to offer some of these financial options, particular leases and PPAs.8

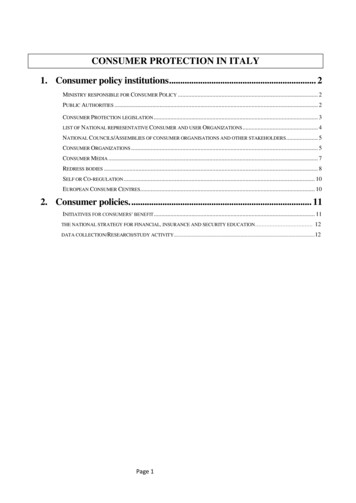

Customer Ownership of the Rooftop Solar System:Customer Purchase: The homeowner obtains their own financing (often in the formof a home equity loan) to purchase the system and there is no ongoing relationshipbetween the homeowner and the solar company after the installation of the systemother than potential repair and maintenance or warranty issues.Loan Agreement: The homeowner enters into a loan agreement with the solarcompany to finance the purchase price of the system, thus eliminating thehomeowner’s obligation to obtain their own loan. Solar companies that offer thismodel have entered into agreements with financial institutions to support their loanoffers and these terms may differ from what the homeowner might be able to obtainindividually.Third-Party Ownership of the Rooftop Solar System:Purchase Power Agreement (PPA): The solar company retains ownership of the solarsystem and the homeowner buys all of the electricity produced by the solar systemat an agreed-upon price per kWh. This price typically rises over the term of thecontract. The homeowner typically is not required to invest any significant capitalcosts. PPAs are usually longer-term contracts with terms of up to 20 years.Lease: The homeowner enters into a lease agreement and makes pre-establishedmonthly payments to the solar company, who retains ownership of the system forthe contract term. In effect, the homeowner is renting the solar system and has theright to use all the power produced by it. The lease payments typically rise yearlyover the contract term and are not tied to the output of the system. Unless thecontract includes a performance guarantee, the homeowner could experiencehigher or lower electric bills depending on the electrical output assumed at the timeof the transaction.The following chart summarizes the different attributes associated with a loan, alease, and a PPA:9

Purchase with LoanTypes of Loans includesecured and unsecured solarloans, home equity loans,home equity line of credit andPACE loansMeet qualifications, such asminimum credit score.Terms of 5-20 years; 3.5-7.5%interest rates. Some statesoffer subsidized loans.Interest on a loan may be taxdeductible.Purchaser retains anyincentives and tax credit.Homeowner owns the systemand is responsible formaintenance.Consumer makes loanpayments. Has the right to useall of the power produced bythe system.At the end of the loan periodthe consumer owns thesystem.System transfers at sale ofhome.LeaseTypes of leases include 0down or a custom downpayment, with monthlypayments that typicallyescalate each year. Option topre-pay (functions like a cashpurchase, with the leasingcompany retaining all taxcredits and rebates).Typically a minimum creditscore is required, but notalwaysContract for 20-25 year periodPPASame as leaseLeasing company retains anyincentives and tax credits.Leasing company owns andmaintains system. However,consumer may have somemaintenance responsibilities,such as tree trimming.Consumer pays a monthlylease payment in exchange forthe right to use all of thepower produced by thesystem. If the system producesless power than predicted, thecost will be higher.At the end of the lease theconsumer can buy the systemat the fair market value orprice specified in the lease;have the company remove thesystem or renew the lease.How is fair market valuedetermined?Buyer may have to qualify totake over lease payments orseller may be required topurchase system before sale.Same as leaseSame as leaseSame as leaseSame as lease.Consumer agrees to buy thepower generated by thesystem at a set price per kWh.Same as leaseSame as lease.10

Whether loan, lease or PPA, these are significant financial outlays for a consumer,potentially with terms that may not be fully understood by, or necessarily favorable to, thepurchaser. While certain policies relating to residential solar, such as net metering, remaincontroversial, there is a growing awareness of the need for developing and implementingbasic consumer protection polices relating to the sale and leasing of solar systems.11

CHAPTER II: IT IS DIFFICULT TO SHOP AND COMPARE COSTS FORROOFTOP SOLAR AND THE PROJECTED IMPACTS ON A RESIDENTIALCUSTOMER ELECTRIC BILLWhen shopping for a rooftop solar system, customers are presented with a widevariety of options that include outright purchase, a purchase power agreement, a lease, or aloan. Customers may hear about solar power options directly from marketers in the formof telemarketing sales calls, door-to-door marketing, web-based advertisements, andrecommendations from neighbors and friends. While the idea of solar power is fairlysimple to explain—install solar panels on the homeowner’s roof--it is not easy tocomparison shop for a residential roof top solar system. Whether purchased or leased, theconsumer is making a long-term financial commitment with the expectation that savings onutility bills will offset the monthly cost of the system. Achieving these savings in reality isdependent on a variety of factors—including contract terms, federal, state, and localsubsidies, the estimated increase in the customer’s cost of electricity, and the performanceof the solar panels themselves. While some or even all prospective customers may also bemotivated by the environmental attributes of solar systems and their potential to displacethe greenhouse gas or carbon emissions associated with more traditional power plants,most consumers also expect benefits in the form of a reduced monthly electric bill. Thesavings potential for rooftop solar systems is particularly important to customers whocannot afford to finance the purchase of the solar system themselves.A.SOLAR COMPANY WEBSITES OFTEN MAKE GENERIC STATEMENTS AND DONOT EXPLAIN MANY DETAILS OF THE PROPOSED TRANSACTIONA review of some of the top solar company websites8 reveals the potential for confusionand confirms the difficulty of shopping and comparing the various options or determiningthe projected savings in the customer’s monthly electric bill. In almost every case, the solarcompany’s website makes generic statements about electric bill savings, but asks thecustomer to call or email (and then receive a sales call) for a price quote. The solar company Brite’s website promotes a residential customer lease(http://www.britelease.com/ ). While there are no sample lease documents available onthis website, the Company offers a no down payment 15-year lease with a performanceguarantee and claim that consumers “start saving immediately.” The site states thatelectricity rates rise an average of 5 to 6 % annually. In fine print, the customer is informedthat there is a 2.5% annual escalation in lease payments. The website does not include anylinks to brochures, references, or educational materials. Sun Edison (www.sunedison.com ) only offers purchase power agreements for residentialsolar in six states. While the website promotes “potential savings,” there are no explicitpromises or estimates of savings and the “frequently asked questions” portion of thewebsite generally identifies the customer specific information needed to calculate benefitsand costs. The company’s solar system is promoted as a long term investment to reduce theelectric bill, add value to the sale of the home, and as an action to reduce carbon emissions:12

I don’t plan on being in my home for 20 years, why would I add solar?Regardless of how long you’ll be in your home it always makes sense to go solar formany reasons. Financially, you will be saving money the first month you go solarand every month you are in the home. You’ll also be able to sell your home for moreas a result because it is a more energy efficient home. Lastly you’ll be reducing yourcarbon footprint by not using the dirty energy that the utility companies currentlyprovide. An effect that will not only be felt by you but by your children andgrandchildren.Will my system increase the value of my home?Yes! The amount depends on the market conditions at the time you sell your home,the area of the country you live in and the amount of money you are saving.However, most homes will appraise anywhere from 5,000- 15,000 more.SunEdison’s website explains that the Company will not charge the customer any upfront costsfor the installation of the new solar system and the customer will pay for the energy that thesolar system generates, “at a rate typically that is lower than you are currently providing” (sic).Specifically, “After all of the free equipment, maintenance, and monitoring, the only thing youhave to pay for with our PPA is the power your solar panels produce. We lock in a rate that isusually less than your local utility company’s market rate—which means you’re free from thevolatility of future rate increases. Plus, if you produce more power than you use, we put it backon the grid and you get a credit from your utility company. If you produce less power than youneed you can still

The U.S. residential solar market has experienced explosive growth in the last five years, fueled by lower costs, state and federal incentives, and new financing options, including leases and purchased power agreements, also known as third-party ownership. Community solar, where a consumer subscribes to shares in a solar system that is located