Transcription

Adaptive PlanningNot YourGreat Grandfather’sSchlieffen PlanSoldiers conduct combinedarms rehearsal inAfghanistan to establishplan of action for nextday’s missionBG Mark T.Kimmitt, USA,chief militaryspokesman forthe CoalitionProvisionalAuthority, and DanSenor, CoalitionInformation Centerdirector, briefpress on handoverof responsibilitiesto the IraqigovernmentU.S. Army (Michael Zuk)By R o b e r t M . K l e i nU.S. Air Force (Jacob N. Bailey)Background: Demolished Iraqi vehiclesline roadway in Euphrates River Valleyafter Operation Desert StormDOD (Dean Wagner)On December 13,2005, Secretary of DefenseDonald Rumsfeld approvedthe Adaptive Planning (AP)Roadmap and directed its “expeditiousimplementation.”1 This act represented asignificant shift in the way the Departmentof Defense (DOD) thinks about militaryplanning. The impetus for change was arecognition that the accelerating pace andcomplexity of military operations requirethat the President, Secretary of Defense, andcombatant commanders have the abilityto respond quickly to new threats andchallenges.Adaptive Planning is the joint capabilityto create and revise plans rapidly and systematically, as circumstances require. It occursin a networked, collaborative environment,requires the regular involvement of seniorleaders, and results in plans containing arange of viable options that can be adaptedto defeat or deter an adversary to achievenational objectives. At full maturity, AP willformthe backbone of a jointadaptive system supporting the developmentand execution of plans, preserving the bestcharacteristics of present-day contingencyand crisis planning with a common process.The need to overhaul the DOD planningand execution system becomes more evidentwhen it is viewed against the backdrop ofhistory. Planning today is a late 19th-centuryconcept born out of the German general staffsystem. It thus seems fitting that a discussionabout transforming the planning processbegins with the history of the Schlieffen Plan.A Fatal AssumptionFrom a strategic and military perspective, the Schlieffen Plan represented animaginative solution to Germany’s strategicchallenge of being sandwiched between avengeful France and a hostile Russia. Moreover, it offered the real prospect of using strategic maneuver to overcome technologicalLieutenant Colonel Robert M. Klein, USA, is a War Planner in the Joint Operational War Plans Division (J7) atthe Joint Staff.84 JFQ/ issue 45, 2 d quarter 2007advances in firepower andthe lethality of warfare between 1870 and1914. Named for its author, Alfred Graf vonSchlieffen, the plan called for rapid mobilization and the swift defeat of France with aholding action against Russia.But the plan’s key assumption, thatGermany could mobilize before France orRussia, proved its fatal flaw. Mobilization wastied to such precise timetables that once thetrains began to roll, any attempt to stop themwould cause mass disruption—a potentiallylethal decision if the corresponding enemytroop trains continued to the frontiers.Contingent on Germany’s ability tomobilize quickly, the plan backed politicaldecisionmakers into a corner by limitingoptions and time to negotiate. Moreover, theevent of either French or Russian mobilizationwas tantamount to a German declaration ofwar on both nations. The Schlieffen Plan andequivalent schemes of the other great powerscomprised a classic example of game theory,n d upress.ndu.edu

Form ApprovedOMB No. 0704-0188Report Documentation PagePublic reporting burden for the collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instructions, searching existing data sources, gathering andmaintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information,including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington Headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, ArlingtonVA 22202-4302. Respondents should be aware that notwithstanding any other provision of law, no person shall be subject to a penalty for failing to comply with a collection of information if itdoes not display a currently valid OMB control number.1. REPORT DATE3. DATES COVERED2. REPORT TYPE200700-00-2007 to 00-00-20074. TITLE AND SUBTITLE5a. CONTRACT NUMBERAdaptive Planning Not Your Great Grandfather’s Schlieffen Plan5b. GRANT NUMBER5c. PROGRAM ELEMENT NUMBER6. AUTHOR(S)5d. PROJECT NUMBER5e. TASK NUMBER5f. WORK UNIT NUMBER7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES)National Defense University,Institute for National Strategic Studies,2605th Avenue SW Fort Lesley J. McNair,Washington,DC,203199. SPONSORING/MONITORING AGENCY NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES)8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATIONREPORT NUMBER10. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S ACRONYM(S)11. SPONSOR/MONITOR’S REPORTNUMBER(S)12. DISTRIBUTION/AVAILABILITY STATEMENTApproved for public release; distribution unlimited13. SUPPLEMENTARY NOTES14. ABSTRACT15. SUBJECT TERMS16. SECURITY CLASSIFICATION OF:a. REPORTb. ABSTRACTc. THIS PAGEunclassifiedunclassifiedunclassified17. LIMITATION OFABSTRACT18. NUMBEROF PAGESSame asReport (SAR)519a. NAME OFRESPONSIBLE PERSONStandard Form 298 (Rev. 8-98)Prescribed by ANSI Std Z39-18

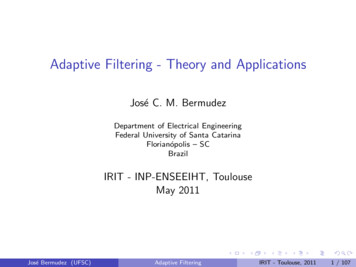

Ro b e rt K l e i noutlined Operations Plan (OPLAN) 1003, theinvasion of Iraq. Secretary Rumsfeld foundthe existing plan frustrating. Essentially areplay of Operation Desert Storm in 1991, itcalled for a slow, massive logistic buildup tosupport an invasion force of 500,000. Themethodical scheme with its months-longtimeline did not square with the Secretary’sideas for a transformed military. The plan hadbeen on the shelf since its approval in 1996and was updated in 1998, but its assumptions,as Secretary Rumsfeld quickly pointed out,were woefully out of date and did not reflectcurrent intelligence.In a meetingThe Schlieffen Planin which all players try to maximize returns.To a large measure, the rulers of Europe, whobungled their way to war in August 1914,became victims of their own planning.2Following World War I, the U.S. militarybegan to formalize a planning process, and theresult was the elaborate series of proceduresknown as the Colored Plans. These arrangements provided the basis for strategy, as wellas joint and combined operations, in WorldWar II.3 Planning improvements in the secondhalf of the 20th century included the JointOperational Planning and Execution SystemFigure 1.n Single optionn Great plan for original assumptionsn Detailed movement tables andmobilization timelines built tosupport single optionn Not adaptive to changingcircumstances and strategicdecision dynamicsn Mobilization and movementtimelines backed policymakersinto strategic cornerFigure 2.“The outbreak of war in 1914 is the most tragic example of government’s helplessdependence on the planning of strategists that history has ever seen.”—Gerhard Ritter, author of The Schlieffen Plan: Critique of a Mythprocess into a capability suited to rapidlychanging conditions.Simply put, the 24-month contingencyplanning cycle was too slow and inflexibleto keep up with fast-paced world events andaltered planning considerations. As OperationIraqi Freedom demonstrated, off-the-shelfplans were static, difficult to adapt, and oftenbased on outdated assumptions, assessments,forces, and circumstances. Since no formalmechanisms existed to ensure early andfrequent consultation between civilian andmilitary leadership during plan development,political leaders entering the cycle at the endwere presented with a fait accompli—a singlen D efensive optionn Original assumptions,assessments, forces not relevantto actual situationn Policymakers wanted multipleoptions, to include offensive optionn Planning process and technologymade it difficult to modify plan andput into execution quicklyn Required extraordinary effort to adaptplan successfully to rapidly changingstrategic circumstancesn The 1003V planning effort providesthe conceptual baseline for theAdaptive Planning initiative“Today’s environment demands a system that quickly produces highquality plans that are adaptive to changing circumstances.”—Secretary of Defense Donald H. Rumsfeld, AP Roadmap, December 13, 2005and its codification in jointdoctrine, policies, and instructions by the mid1990s. Despite these and other institutionalimprovements (in areas such as mobilizationand transportation planning), modern planners failed to address the dilemmas that hadplagued all contingency plans since the inception of the Schlieffen Plan. Most critically,contingency planning remained a flawed,time-consuming process, bound by the original assumptions and largely unresponsive tothe demands of political decisionmakers whorequired more options. This reality was nevermore evident than in the events leading up tothe invasion of Iraq in March 2003.On November 26, 2001, SecretaryRumsfeld flew to Tampa to see GeneralTommy Franks, commander, U.S. CentralCommand. In a private session (Rumsfeldinsisted that they be alone), General Franksndupres s.ndu.eduon December 4, Rumsfelddemanded alternatives and out-of-the-boxthinking. How would the plan be executedon short notice versus an extended timeline?What was the shortest period required todeliver enough forces to accomplish themission? What if the President was willingto accept more risk? Despite obvious flaws,OPLAN 1003 was the only one on the shelf ifthe President decided to go to war with Iraqimmediately. A complete rewrite of a contingency plan would take months.4The MandateFrom the months-long planning priorto Operation Iraqi Freedom, it became evidentthat a complete overhaul would be required totransform the DOD industrial age planningmilitary option that boundpolitical decisionmaking in time-constrainedsituations.This setting was disturbingly similarto what happened with the Schlieffen Plan in1914 (see figures 1 and 2). Clearly, contingencyplans needed to incorporate more and betteroptions and sufficient branches and sequelsthat readily lent themselves to rapid andregular updating to support crisis planningand execution.5Compounding the problem, joint planning has been largely sequential, requiringiterative collocation of planners from seniorand subordinate organizations. Becauseauthoritative data have been compartmentedissue 45, 2 d quarter 2007 / JFQ85

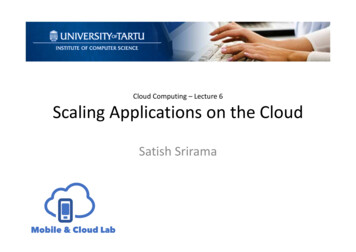

Adaptive Planningand are not readily accessible for planning,course of action development remains a prolonged process, necessitating requirementsidentification and feasibility analyses (operational, logistic, and transportation) late in theplanning process, causing time-consumingadjustments and extending development timelines even further.Also, interagency involvement generallyoccurs late in plan development. OperationPlans Annex V, which addresses interagencycoordination, is typically written afterapproval of the base plan. Despite advancesin information technology, joint plannersremained stuck in the 20th century, havingfew tools to enable work in parallel acrossechelons in a virtual environment with accessto key planning data.At the direction of the Secretary ofDefense, the Principal Deputy Under Secretary of Defense for Policy tasked the DeputyAssistant Secretary of Defense for Resourcesand Plans in August 2003 to work with theJoint Staff to create a successor to currentplanning processes. Specifically, he sought anapproach that would considerably shorten thetime it takes to produce plans and to createplans that can be adapted to a constantlychanging strategic landscape.6 The result wasAdaptive Planning.Background: Line of Bradley Fighting Vehicles used in Operation Desert StormAdaptive Planning VisionThe 2005 Contingency Planning Guidance directed combatant commanders todevelop designated, priority contingencyplans using the AP approach. Transformingcontingency planning requires modernizingthe way DOD thinks about and develops itsprocesses, products, people, and technologyfor planning.7 This transformation does notentail complete elimination of current processes. Rather, it requires a mixture of newand existing capabilities. The Department ofDefense must preserve the best characteristicsof current processes and systems and applythem in unprecedented ways.AP allows combatant commanders toproduce plans more quickly and adaptivelyand of higher quality. Rapid planning andgreater efficiency are achieved through combining multiple stovepiped processes into onecommon AP process that includes:n clear strategic guidance and iterativedialoguen integrated interagency and coalitionplanning86 JFQ/ issue 45, 2 d quarter 2007Current and Adaptive Planning ProcessesUp to 24 Months or More for Deliberate PlanningPhase IInitiationPhase IIConceptDevelopmentPhase IIConceptReviewPhase IIIPlanDevelopmentPhase ISituationAwarenessCurrent ProcessPhase IVPlanReviewPhase IIPlanningPhase VSupportingPlansPhase IIIExecutionMonths to Days for Crisis PlanningMonths to Days for Plannin gAP ted intelligence planningembedded optionsn living plansn parallel planning in a network-centric,collaborative environment.nnThe end result is that Adaptive Planningfor any single strategy implies that resourcerequirements are dynamically allocated andrisk is continuously balanced against otherplans and operations.Clear Strategic Guidance and IterativeDialogue. AP combines the best characteristics of contingency, crisis action planning,and execution into a single integrated process.Strategic guidance is the first step in the fourstage planning process, which also includesconcept development, plan development, andplan assessment. Each step includes as manyin-progress reviews (IPRs) by the Secretaryas necessary to complete the plan. Althoughthese steps are generally sequential, they mayoverlap in the interest of accelerating theoverall process.AP speeds the procedure by providingmore detailed and focused initial guidance inthe DOD planning documents: contingencyplanning guidance, joint strategic capabilities plan, and strategic guidance statements.Strategic guidance also includes interagencyguidance, intelligence assessments, and otherdirection from the Secretary during IPRs.At the combatant command level, planningbegins with the receipt of strategic guidanceand lasts through final plan approval intoa continuous plan-assessment cycle. Ultimately, AP envisions streamlined strategicguidance that feeds war planning throughregular updates over a network-centric, collaborative environment.IPRsFunctionPlanAssessmentFigure 3.Adaptive Planning reviews representa departure from the previous planningprocesses, both in frequency and form.The intent is senior leader involvementthroughout the process, including periodicreviews once the plan is complete. The initialIPRs focus largely on solidifying guidance,agreeing on the framework assumptions andplanning factors, establishing a commonunderstanding of the adversary and his intention, and producing an approved combatantcommander mission statement.Subsequent IPRs may revisit, refine,modify, or amend these outcomes as required.Additionally, they will address risks, coursesof action, implementing actions, and otherkey factors. Timely reviews and IPRs ensurethat the plan remains relevant to the situationand the Secretary’s intent as plans are rapidlymodified throughout development andexecution. Figure 3 illustrates how IPRs areintegrated throughout the AP process.Under AP, planning will be expeditedby guidance that specifies the level of detailrequired for each situation. The amount ofdetail needed is tied to the plan’s importanceand likelihood of execution. This helpscombatant commanders manage planningin the near term. There are four levels ofplans under AP. Level 1 requires the leastdetail, level 4 the most. Strategic guidance inthe contingency planning guidance and thejoint strategic capabilities plan will identifythe level to produce. However, the Secretarymay increase or decrease the level of detailrequired in response to changed circumstances, changes in a plan’s assumptions, ora combatant commander’s recommendation.The Secretary and the combatant commander confer during IPRs on the nature andn d upress.ndu.edu

Ro b e rt K l e i nndupres s.ndu.edurequire review at least every 6 months. As aachieve the combatant commander’s desiredresult, living plans provide a solid foundationeffects of the operational objectives. Additionfor transition to crisis planning. Additionally,ally, the process will focus on developing themilitary and political leaders are better able tointelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissancegauge and mitigate risk across multiple plansstrategy and synchronize the requisite inteland better comprehend the collateral impactsligence support. Because the intelligence camof execution and changed circumstances.paign plan is directly linked to contingencyParallel Planning in a Network-Centric,planning, changes in the global strategic enviCollaborative Environment. The developmentronment continually feed plan developmentof a network-centric information architectureand assessment.provides an opportunity to modernize theEmbedded Options. AP features ancontingency planning process. Plans, planincreased number of options, as well asning tools, and pertinent databases will bebranches and sequels (along with associlinked in a network-centric environment,ated decision points and decision criteria),whose architecture will enable collaborain order to provide the President, Secretary,tion among widely separated planners at alland combatant commanders with increasedcommand echelons, promoting a better graspexecution flexibility that anticipates andof the operational environment and morerapidly adapts. Such embedded options makeeffective parallel planning. Authoritativeplans more dynamic.internal and external databases will be linkedThe term embedded options conveysto promote the timely exchange of informathe idea that branches and sequels, in at leasttion based on appropriate access rules. Newoutline fashion, are identified and developedplanning tools will be developed to allow this.as an integral part of the base plan coursesAdaptive Planning for any single planof action. Branches and sequels traditionallyimplies a mission-based readiness systemhave been developed toward the end of theand dynamic force management and logisticprocess, often after the base plan is completed.systems integrated by a common suite ofUnder AP, embedded branches and sequelsautomated planning tools. This requireswill form an integral part of base plan designthat the defense readiness and Global Forceand development. As AP matures, technologyManagement processes operate acrosswill enable combatant command planners tomultiple plans and operations to allocatedevelop an extensive menu of such branchesresources and balance risk.and options rapidly, well beyond what hasBoth identifying and sourcing requirepreviously been practicable. Base plans mayments are necessary to determine force, transeventually become a “menu of options” toportation, and logistic feasibility. Approvedexecute based on exigent circumstances.courses of action must often be adapted toLiving Plans. What distinguishes currentrender them feasible, causing delays in theplanning from AP is that the latter doesprocess. Automated collaborative tools willnot allow ideas to sit on the shelf. The finalallow planners to develop these options, deterstep, plan assessment, represents a “living”mine their feasibility, and incorporate themenvironment in which plans are refined,into the concept of the operation, rather thanadapted, terminated, or executed (referred todeveloping them after the base plan and selectas RATE-ing a plan). At full maturity, AP willannexes are completed. Analysis includesproduce network-centric living plans. A livingwargaming, operational modeling, and initialplan is maintained within a collaborative,feasibility assessments. Joint wargamingvirtual environment and is updated routinelytools will allow planners to visualize the planto reflect changes in intelligence assessto analyze the operational feasibility, risk,ments, readiness, Global Force Management,and sustainability of courses of action. Intransportation availability, guidance, assumpAP, feasibility analysis occurs much earliertions, and the strategic environment. Bothin the process than previously possible. Theautomatic and manually evaluated triggerscapabilities to conduct detailed assessmentslinked to real-time sources will alert leadersand planners to changes incritical conditions that warrant aboth identifying and sourcing requirementsrevaluation of a plan’s relevancy,feasibility, and risk. Top-priorityare necessary to determine force,plans and ideas designated in thetransportation, and logistic feasibilitycontingency planning guidanceU.S. Army (Gary W. Butterworth)detail of planning needed, including branchesand options to be developed.Integrated Interagency and CoalitionPlanning. The past decade of complex operations, from Somalia to Iraq, has demonstrated that strategic success requires unityof effort not only from the military but alsofrom the U.S. Government and coalitionpartners. Time and again, the United Statesand its partners have come short of fullyintegrating the diplomatic, informational,military, economic, and other dimensionsof power into a coherent strategy. One factorthat has contributed to this poor performance is lack of a unified approach to planning. AP recognizes that interagency andcoalition considerations are intrinsic ratherthan optional and need to be integratedearly in the process rather than as an afterthought once the military plan is complete.To this end, the combatant commandermay seek approval and guidance from theSecretary to conduct interagency and coalition planning and coordination. The goalis to ensure that interagency and coalitioncapabilities, objectives, and endstates are considered up front in the process. This holisticeffects-based approach to planning ensures thatcorrect national or coalition instruments areemployed to match the desired ends. As partof the planning process, and with approvalof the Secretary, the combatant commandermay present his plan’s Annex V (InteragencyCoordination) to the Office of the Secretaryof Defense/Joint Staff Annex V WorkingGroup for transmittal to the National SecurityCouncil for managed interagency staffing andplan development. In advance of authorizationfor formal transmittal of Annex V, the commander may request interagency consultation on approved Annex V elements by theOffice of the Secretary of Defense/Joint StaffWorking Group. Concurrently, the combatantcommander may present his plan for multinational involvement.Integrated Intelligence Planning. Intelligence campaign planning provides a methodology for synchronizing, integrating, andmanaging all available combatant commandand national intelligence capabilities withcombatant command planning and operations. Throughout the planning process, thecombatant command J2, in coordination withthe Joint Staff J2 and U.S. Strategic Command,will continue leading DOD through the intelligence campaign planning process, whichdevelops the intelligence tasks required toissue 45, 2 d quarter 2007 / JFQ87

Adaptive Planningin a matter of days rather than months are asignificant leap forward.By leveraging emerging technologiesand developing initiatives, DOD can createan integrated planning architecture in whichdata is shared seamlessly among users,applications, and platforms. At present, thecombatant commands and Services use avariety of tools for planning that have nearterm utility in supporting AP. Tools that couldbe rapidly developed and acquired constitutean area of special interest. The result will bea compressed decisionmaking cycle with anenhanced understanding of how decisionsaffect campaigns.As part of spiral development, combatant commands are currently using the APprocess to build several of the Nation’s highestpriority war plans. Nevertheless, at full maturity, Adaptive Planning envisions transparency between contingency and crisis actionplanning enabled by integrating readinesswith Global Force Management processes thatdynamically allocate resources and balancerisks across multiple plans and operations.The implementation of Adaptive Planningrequires spiral development through threestages: initiation, implementation, and integration. This approach will enable the Department of Defense to begin Adaptive Planningimmediately for selected priority plans, learnfrom that, and evolve to a mature process.Requirements for every successive stage—eachproviding planners with a more sophisticatedcapability—will depend on stakeholder feedback and technology maturation.NDU Topical SymposiumApplyingSpacepowerSavethe Date. . .For a relatively modest investment,Adaptive Planning may have a significantstrategic impact, creating situations in whichthe President, Secretary of Defense, and othersenior leaders play a central role by selectingApril 25–26, 2007NDU is hosting this capstoneconference following a year-longproject assessing the uses ofspace.Experts will present proposals forapplying space as an element ofnational power across the civil,commercial, military, and intelligence sectors.88 JFQ/ issue 45, 2 d quarter 2007N otesThis article borrows heavily from the Adaptive Planning Roadmap (December 13, 2005).2See Adam Gropnik, “The Big One,” The NewYorker (August 23, 2004), available at www.newyorker.com/printables/critics/040823crat atlarge .3See Henry G. Gole, The Road to Rainbow:Army Planning for Global War, 1934–1940 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2002).4Bob Woodward, Plan of Attack (New York:Simon and Schuster, 2004), 35–44.5Branches and sequels provide the commanderwith alternatives and follow-on options beyond thebasic plan and should similarly have entry and exitcriteria.6Ryan Henry, Adaptive Planning memorandum, August 26, 2003.7Adaptive Planning has combined sevencategories—doctrine, organization, training, material, leadership, personnel, and facilities—into four:processes, products, people, and technology.1Marine uses large sandtable to brief troops onwar plans and positionsduring OperationEnduring FreedomDOD (Andrew P. Roufs)Contact: NDU Conferences@ndu.edu orvisit the NDU Web site (www.ndu.edu) forinformation on the agenda and registrationfrom multiple, viable options adaptable to avariety of circumstances. Gone are the daysof outdated, single option, off-the-shelf plansof the Schlieffen and OPLAN 1003 variety. Asthe fluid strategic situation unfolds, emplacedtriggers will alert planners to the need formodifications or revisions to keep plansrelevant based on further strategic guidance,continuous intelligence assessment of threatassumptions, rapid force/logistic management processes, and mission-based readinesssystems. The confluence of these capabilitiesrepresents a quantum leap that will finallyallow the planning community to break thebounds of the Schlieffen Plan and enter the21st century. JFQn d upress.ndu.edu

adaptive system supporting the development and execution of plans, preserving the best characteristics of present-day contingency and crisis planning with a common process. The need to overhaul the DOD planning and execution system becomes more evident when it is viewed against the backdrop of history. Planning today is a late 19th-century