Transcription

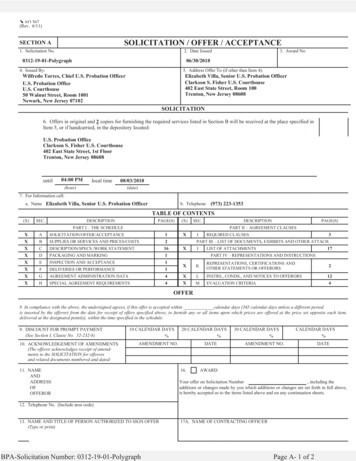

Handler, Honts, Krapohl, Nelson & GriffinIntegration of Pre-Employment Polygraph Screening into thePolice Selection ProcessMark Handler1, Charles R. Honts2, Donald J. Krapohl3,Raymond Nelson4, and Stephen Griffin5AbstractThe authors provide a polygraph primer for police psychologists involved in law enforcementpersonnel selection. Law-enforcement pre-employment polygraph examinations are a decisionsupport tool intended to add incremental validity to the personnel selection process. Problemsstemming from the use of the polygraph may be related to misunderstanding of the polygraph testand to field practices surrounding the use of polygraphy in the police selection process. Potentialproblems can result from ineffective selection of test issues, poorly constructed test questions andmisguided policies surrounding the use of the polygraph. The authors review polygraph screeninghistory, research, and field practices, and suggest that using polygraph results alone to disqualifya candidate from employment is a misguided field practice. Suggestions are offered for maximizingthe decision-support value of the polygraph. Polygraph examination targets are discussed, withemphasis on selecting actuarially derived predictors associated with increased success in lawenforcement training and job performance. The authors provide recommendations for fieldpractice, and propose that police psychologists may be most suited to effectively integrate thepolygraph results and information into the hiring recommendation process.argued as supportive of the opinions held byboth proponents and opponents of polygraphtesting.Opponentsalsoquestiontheconstruct validity and ethics surrounding howconsumers use polygraph results, and suggestthat polygraph results may be unrelated todesired outcomes.IntroductionPolygraph testing has a long andcontentious history in the arena of socialscience. Perhaps nowhere has there beenmore controversy than that which surroundsscreening uses of the polygraph test.Advocates emphasize the utility of informationgleaned through polygraph testing while thoseopposed question the validity of the fieldresults and the generalizability of analogstudies. A comprehensive review of diagnosticand screening applications of polygraphy bythe esteemed National Academies of Science(NRC, 2003) reported results that could beThe application of polygraph in apublic safety pre-employment screening iscomplex from the outset, and is bestunderstood by starting with brief review of theputative psycho-physiological concepts thatunderlie polygraph techniques, procedures,and test interpretation. These issues should1AmericanAssociation of Police PolygraphistsState University3APA Past President4Private Practice5Institute for Personality and Ability Testing, Inc.2BoiseAuthors’ Note: The authors are grateful to Dr. Michael G. Aamodt, Dr. Stuart Senter, and Ben Blalock, for theirthoughtful reviews and comments to earlier drafts of this paper. The views expressed in this article are solely thoseof the authors, and do not necessarily represent those of the Department of Defense, the American Association ofPolice Polygraphists, or the Institute for Personality and Ability Testing, Inc. Questions and comments are welcomeat polygraphmark@gmail.com.This article was originally published in the Journal of Police & Criminal Psychology (2009), vol. 24, issue 2, pp 69-86,and is reprinted here with the kind permission of that journal. Minor editing of the original work has been done tobring the article into conformity with the style and format of the journal Polygraph.239Polygraph, 2009, 38(4)

Pre-Employment Polygraph Screeningbe understood in the more general context ofthe inherent complications that are commonto all screening tests. Because it is unrealisticto expect perfection from any test, med consumers of polygraph test resultsshould become familiar with common testingconcepts including sensitivity, specificity, , and base-rate influences along withthe ways that these may affect polygraphscreening outcomes. We suggest that validityand reliability of current polygraph fieldpractices may be improved through increasedemphasis on the selection of polygraphexamination targets for which there isevidence of their actuarial contribution todesired outcomes. We further suggestpolygraph results and information may bemost effectively employed in the context of a“whole person” approach to evaluating lawenforcement applicants. This approach maybe best guided by the efforts of police orindustrial psychologists whose training inpsychodiagnostics and empirical methods willallow them to effectively navigate potentiallypositive and negative aspects which thepolygraph offers to the police personnelselection process.Polygraph screening was used toscreen employees as early as the 1930s whenLeonarde Keeler signed an agreement with theinsurance firm Lloyds of London toperiodicallytestbankemployeesforembezzlement (Alder, 2007). By the 1940s,polygraph screening tests were conducted onGerman prisoners of war for potential postwar law enforcement positions (Linehan,1978). One of the earliest large-scale testingprograms was that of the Manhattan Districtof the Corps of Engineers which began vettingpotential employees for the Oak Ridge nuclearweapons facility in 1946 (Linehan, 1990). Thistesting program was considered by some to besuccessful in that it contributed to the returnof many previously stolen tools and suppliesand elicited admissions of serious workrelated transgressions such as unreportedspills of radioactive materials. The AtomicEnergy Commission, however, discontinuedthe polygraph screening program in April,1953, in part because the program was seenas providing only marginally increasedsecurity (Krapohl, 2002). Polygraph screeninggained popularity in the United States privatesector during the 1970s and 1980s. As manyas 2 million Americans a year were beingtested, mostly in the private sector, by the1980s (Alder, 2007).Our ultimate goal is to suggest thepolygraph can be a valuable tool, at thedisposalofthepoliceorindustrialpsychologist, to help them make betterrecommendations to law enforcement hiringofficials faced with the difficult puzzle ofdetermining just who to screen-in or screenout of the law enforcement selection process.The US Congress enacted the 1988Employee Polygraph Protection Act (EPPA) tocurtail among other things, abuses reportedas a result of the widespread use of polygraph.Problems observed prior to EPPA includedpoorly standardized and unregulated fieldpractices, and inadequately standardizedtraining for field practitioners, and includedcost-cutting and other competitive marketingefforts that led to the proliferation of “chartrolling” practices which included the remostamongthoseproblems was the selection of examinationtargets with unproven contribution to thedesired outcomes of employee trainingsuccess and employee integrity. Despite therestriction imposed by EPPA, there areremainingprovisionsthatallowforgovernment and public safety pre-employmentpolygraph screening (Krapohl, 2002), inaddition to potential screening for employeesin pharmaceutical and nuclear energyindustries.Background and history ofpolygraph screening programsToday,pre-employmentscreeningpolygraph examinations of police applicantsare widespread in the US and elsewhere, andare intended as an aid in the selection ofsuitable applicants. Unlike diagnostic tests,which are used for criminal investigationpolygraphs, screening examinations areconducted in the absence of any knownincident or allegation. Screening polygraphsand screening tests in general, are oftenconstructed to investigate, in a cost effectiveand expedient manner, the applicant’s historyof involvement in a range of possible activitiesof concern to hiring officials.Polygraph, 2009, 38(4)240

Handler, Honts, Krapohl, Nelson & GriffinMeesig and Horvath (1995), inconjunction with the American PolygraphAssociation (APA), conducted a survey todetermine the use of pre-employmentpolygraph testing in 626 law enforcementagencies throughout the United States. Themean force size of the agencies surveyed was447 officers, serving an average population of522,000 citizens. The survey found thatapproximately 62% of the respondent agenciesutilized the polygraph as part of their hiringprocess. The respondent agencies reportedthat they rejected approximately a quarter oftheir applicants as a result of informationproduced through polygraph testing that hadnot been uncovered with their other screeningprocesses.Legal history surrounding polygraphtesting in the United States courtsystemsLegal admissibility of polygraph testresults in the U.S. court systems has a longand colorful past. Perhaps no otherevidentiary offering has been scrutinized to agreater degree than polygraph test results andadmission of polygraph test results into legalproceedings is rare (Daniels, 2002). Concernsinclude whether the polygraph evidence wouldoverwhelm, confuse or supplant the trier ofthe fact. Additionally, issues of validity andreliability of polygraph testing in general arebound to be raised. The popularity and allureof polygraph testing has left no dearth ofstudies from which one may report results.For example, the National Research Council(2003) reported results from 50 laboratorystudies which met their criterion for inclusionin quantitative analysis and that aloneincluded 3,099 polygraph examinations. Anumber of published studies were excludedbecause they did not meet their criteria forinclusion (NRC, 2003).The Meesig and Horvath (1995) surveyrevealed that previous illegal drug use was themain content of the information gathered as aresult of polygraph, but criminal activitieswere also disclosed. Respondent agenciesreported that the polygraph screeninguncovered information indicating involvementby some applicants in unsolved homicides(9%), perpetration of rape by applicants (34%),and commission of armed robberies (38%).The majority of these agencies felt polygraphtesting was as useful as (or better than) otherforms of vetting, including backgroundinvestigation, written psychological l interviews, and interviews by aselection board.American polygraph law was theimpetus for the “General acceptance in thescientific community” test which has beenreferred to as the “Frye test” in honor of thecase that set the precedent, Frye v. UnitedStates (Daniels, 2002). Defendant Frye wasconvictedofmurderingaprominentWashington, D.C. physician in 1920 (Krapohl& Stern, 2003b). Frye appealed his convictionbased on the trial court’s refusal to admit theresults of a discontinuous systolic bloodpressure “deception test” administered to Fryeby Dr. William Marston (Daniels, 2002;Krapohl & Stern, 2003b). The deception testwas purported to be able to determine veracitybased on periodic sampling of the examinee’ssystolic blood pressure during questioningabout the crime event. This case occurred at atime in history when judges and courts werebeing presented with offerings of new scientificbased evidence, but often without the benefitof testimony on acceptance from the scientificcommunity. The court of appeals upheld thetrial court ruling to not allow Dr. Marston’stestimony regarding the deception test headministered Frye and in doing so establisheda precident for novel scientific evidence thatendured for the next 70 years (Daniels, 2002).The U.S. government is arguably thelargest user of the polygraph (Krapohl, 2002;NRC, 2003). Government polygraph screeningprograms have steadily increased over time,and there are presently in excess of 20 federalpolygraph programs dedicated to screeningapplicants, employees, and contractors foraccess to sensitive information. According toBarland (1999), 69 countries around the worldhave known polygraph capabilities and thatnumber is almost certainly larger today.Polygraph screening programs are in place inboth private and public sectors in the UnitedStates, Mexico, Israel, Japan, South Africa,Bulgaria, Russia, and Canada (Krapohl,2002).241Polygraph, 2009, 38(4)

Pre-Employment Polygraph ScreeningThis “Frye test” required a scientific test tohave gained the general acceptance of thescientific community in the particular fieldfrom which it belongs.share many of the testing principles withdiagnostic polygraph exams used in criminalinvestigations. Commonalities include thebasic principles of question formulation,testing protocol, and instrumentation. Thereare, however, important differences betweenscreening and criminal investigation ordiagnostic polygraphs. Criminal e’s involvement in a known event orknownallegation,whereasscreeningexaminations test for credibility aboutinvolvement in specified patterns or categoriesof behavior, over sometimes lengthy timeperiods, which are empirically correlated withincreased risk for an undesired futureoutcome. For example, a question from adiagnostic or investigative polygraph testmight be, “Did you rob the 1st National Banklast November 4th?” whereas a typicalscreening question might be worded as “Didyou ever commit a serious crime?” The timeperiod for screening exams is necessarilybroader, and instead of referring to a knownallegation or known incident pertaining to aspecific date or period of time, screeningexams may refer to the examinee’s entirelifetime or entire adult lifetime. Screening testquestions may also be limited to a recentperiod of time that will improve the signalvalue and actuarial utility of the targetinformation. For example: “During the last fiveyears, have you had any involvement withillegal drugs?”Several more recent court opinionsappear to allow some opportunity forpolygraph admissibility. In 1989, the federalappeals court in the 11th circuit, opined “aper se disallowing of polygraph evidence is nolonger warranted” in the case of United Statesv. Piccinonna. This decision still stands as ithas not been overruled, but it has not beenfollowed by any other federal jurisdiction(Daniels, 2002). The other recent casepotentially affecting polygraph admissibility is1993 United States Supreme Court decision inDaubert v. Merrell Dow Pharmaceuticals, Inc.(Daubert). While not addressing polygraphspecifically, Daubert addressed the “Frye test”and found it to be too restrictive. The UnitedStates Supreme Court essentially stated in theDaubert opinion that admissibility revolvesaround a number of factors which when takenas a whole allow lower courts some flexibilityin admitting evidence that results fromemerging scientific developments.These factors include:1. is the theory being offered capable ofbeing tested;2. has the error rate for the application ofthe technique been established;3. has the application of the techniquebeen subjected to peer review andpublication;4. is there a known level of acceptance ofthe offered theory by the scientificcommunity most relevant to theparticular theory;5. are there established standards todetermine the correct and acceptableapplication of the technique.Polygraphtestquestionsshouldprovide interpretable and useful informationto the consumer of the test result, regardlessof whether the examinee passes or fails thetest. For test questions to meet thisrequirement, it is necessary that all targetquestions meet certain commonly acceptedcriteria, including that the question describethe examinee’s possible involvement in asingle behavior or single pattern of behavior,can be easily answered ‘yes’ or ‘no,’ does notincluded vague or necessary legal or clinicaljargon, is free of references to motivation orintent, and does not presuppose guilt orinvolvement on the part of the examinee.Behaviors referred to in polygraph testquestions should be supported by aoperational definition that is commonlyunderstood between the examinee, examiner,and the referring professional. Operationaldefinitions provide descriptive informationThe overwhelming trend has been to excludepolygraph evidence from American courtroomsby applying a stringent Daubert interpretationand it seems unlikely that any significantchange to admissibility will occur in the nearfuture (Daniels, 2002).General information aboutpolygraph testingThough they operate in differentdomains, screening polygraph examinationsPolygraph, 2009, 38(4)242

Handler, Honts, Krapohl, Nelson & Griffinabout what one would be observed doing ifone were to engage in a behavior. This hasimportant implications for the validity andutility of the polygraph testing. For example,one could be expected to know with certainty,whether or not one had robbed a bank. Thesame degree of assurance may not beattributable to a question requiring theexaminee to search their memory for whetherthey committed a serious crime. It would be aproblem, for example, if an applicant does notunderstand the hiring agency’s operationaldefinition of what constitutes a serious crimeversus a non-serious crime. An examinee insuch an ambiguous situation, without anadequate operational definition, would befaced with the task of answering a questionabout involvement in serious crimes while atthe same time trying to identify whatseparates a serious from non-serious crime.compromises in the design of test protocols, inordertodifferentiallyprioritizetheseobjectives in diagnostic and screening testcontexts. It is important for administratorsand consumers of polygraph results to remainaware that a small portion of errors of somekind can always be anticipated from any testor procedure.Use of decision theoretic approaches inpolygraph practice has a short history, anduntil recently, there were no serious attemptsamong practitioners to develop a body of bestpractices for screening examinations. This isan unfortunate circumstance that has led toserious problems for the profession as awhole. The lack of practice standards, andother inadequacies, may have contributed tothe passage of EPPA in 1988 which t agencies, as discussed earlier.Moreover, research has confirmed thatpotential inadequacies, such as low sensitivityand/or specificity, existed in polygraphscreening methods employed at the time, evenin the much better controlled environment ofthe U. S. Government (Barland, 1981;Barland, Honts, & Barger 1989; Honts, 1992).As with all tests that renderdichotomous outcomes, there are two correctoutcomes and two types of errors that canoccur with the polygraph. A positive resultsignifies the examinee’s involvement in thebehavior or behavioral category described bythe relevant question. Similarly, a negativeresult suggests the examinee was not involvedin the behavior or behavioral category ofconcern. When a truthful examinee is judgedto be deceptive by a polygraph examiner theerror is called a false positive error, or moresimply a false-positive. Conversely, when adeceptive examinee is judged to be truthful itis a false negative error or false-negative.Along those lines, a true-positive result is onein which a deceptive examinee is correctlyidentified as deceptive and a true–negativewould describe a truthful examinee judged tobe telling the truth. The desired attributes of apolygraph test are identical to the goals ofother forms of testing. It is a requirement ofall effective tests that they provide highenough sensitivity to reliably notice the issuesof concern, thereby avoiding false-negativeerrors. Another desired characteristic ofeffective tests is that of providing highspecificity to the issues of concern, ensuringunrelated factors will not cause false-positiveerrors. Unfortunately, there is no such thingas a perfect test that can perfectly accomplishboth objectives of sensitivity and specificity. Inevery form of testing, there is always a tradeoff or compromise among these objectives.Test developers have learned to make strategicOne current challenge in the field is alack of standardization in test administrationacross the profession. In recent years, a seriesof articles in professional journals and othervenues urged the polygraph profession towardmore data-driven field practices n, Gardner, Webb, 2005; Krapohl,2006; Raskin & Honts, 2002). As an exampleof the trend away from values-based andidiosyncratic field practices, the y developing model policies, includingthose for polygraph screening of policeapplicants and other specialties (AmericanPolygraph Association, 2008). The AmericanSociety for Testing and Materials (ASTM,2008) has promulgated standards for a varietyof polygraph tests and settings. Though not acomplete solution to the problems of ions represent a significant steptoward embracing standardization principlesfound successful in other fields such asmedicine and psychological assessment.243Polygraph, 2009, 38(4)

Pre-Employment Polygraph ScreeningDiagnostic tests are intended to helpformulate a basis for necessary action, andshould provide sufficient specificity to theissue of concern to accurately identifyingpersons not involved in the issue �s burden of suspicion. In actualfield practice, decision schemes for diagnosticpolygraph tests are typically risk-aversive.That is, they are deliberately set to ensurethat a guilty suspect remains on theinvestigative radar.user by improving overall decision accuracyover mere screening, while mitigating costsover the use of multiple diagnostic tests. Theeffect of ensuring that every possibleunsuitable candidate is identified andeliminated from the pool of eligible applicantswill inevitably result in the elimination ofsome suitable candidates. A comprehensiveprogram would respond to all positive testresults (those signaling a significant response)with additional or follow-up investigativeprocedures in response to this known andexpected reduction of test-specificity inscreening situations (NRC, 2003). Ideally,such follow-up investigative procedure wouldemploy methods that offer better specificitythan the initial screening exam, in an effort toreduce the incidence and impact of falsepositive results. These investigative responsesmay include follow-up polygraph testing withmore specific procedures or additionalbackground investigation efforts aimed atclarifying the issue of concern. This methodmayatfirstseemadministrativelycumbersome but the advantages becomeapparent when one considers the costs andexpense of intensive investigative procedures,compared with the expediency that screeningmethods provide.Screening tests should also bedesigned to be risk-aversive, and strive toreduce the likelihood that a problem goesundetected. When the consequences of anerroneous judgment (e.g. that an unsuitablecandidate is hired into a police role) presentpotentially catastrophic ramifications to anagency or community, decision thresholdsshould be set to maximize detection sensitivityto potential problems.Krapohl (2002) and Krapohl and Stern(2003a) discussed the differences betweenscreeninganddiagnosticpolygraphs,including the use of a successive-hurdlesmodel (Meehl & Rosen, 1955) when seeking tomitigate decision errors and maximize theeffectiveness of polygraph testing programs.Diagnostic and screening tests are used inmany fields, and when thoughtfully combinedin the screening domain, these two distincttestingapproachesmayofferuniqueadvantages to both decision makers andconsumers of test results. Screening methodsare generally intended to be a cost effective,though imperfect means of sorting individualsinto tentative categories. Although diagnosticmethods may have substantially moreclassification power than screening methods,they also tend to be more resource-intensive,and are therefore more wisely reserved foronly those individuals who produce positiveresults on the screening tests. Screening testsare therefore useful only when they provideadequate sensitivity to the issue or issues ofconcern. In an effort to maximize thesensitivity levels of screening exams, testdevelopers adopt decision thresholds thatprovide adequate sensitivity to reliably identifythe presence of the issue or issues of concern.A process model, that includes the use ofdiagnostic testing only after a positivescreening result, reaps benefits to the endPolygraph, 2009, 38(4)Polygraph Test TechniquesPolygraph techniques can be dividedinto two major categories, knowledge-basedtests, also called recognition tests, anddeception based tests. The knowledge-basedtests attempt to determine if the examinee hasknowledge only available to persons directlyinvolved in an incident of concern. These testsare commonly known as Guilty KnowledgeTests, or more correctly, as ConcealedInformation Tests (CIT). In a CIT used for amurder case, the polygraph examiner mightassess whether or not the examinee reactsphysiologically to the murder weapon ascompared to a series of possible weaponswhich investigators are certain were not usedin the crime. Because this approach dependsupon the existence of a known crime orincident facts that remain unknown to theinnocent suspect, the CIT testing paradigm isnot suited for use as a screening testconcerning unknown incidents and multipleissues, and will not be discussed further here.244

Handler, Honts, Krapohl, Nelson & GriffinPolygraphscreeningprogramsgenerally rely on deception-based methods.These methods ask directly about the matterto be assessed, are capable of addressingmultiple behavioral issues of concern and donot depend on the existence of a knownincident or known allegation. These featuresmean that these tests are suited for thescreening environment, they are intended toassess an examinee’s credibility regardinginvolvement in behaviors of concern, orconformity to personnel selection standards.While the circumstances and case facts of acriminal investigation drive the selection ofpolygraph questions in a very tions, the issues for police preemployment screening polygraphs are usuallydriven by department policies. Unfortunately,these policies are often more tied topreferences of the leadership than toempirically derived predictors, a factor whichalmost certainly limits the value of thepolygraphscreeningprograms.Ideally,personnel hiring policies would be informed byactuarial data concerning successful trainingand job performance outcomes. An actuariallybased polygraph screening program shoulddeliver information of better predictive valuethan is generally found among current policepolygraph screening programs (Aamodt,2004).data. This has the potential to degrade anyinter-rater agreement in the evaluation byintroducing subjectivity.Raskin and Honts (2002) concludedthat the rationale of the RI technique is naïve,and that the approach does not al test and should not be used inforensic/investigative settings. There is,however, some evidence that shows the RIapproach to screening may have validity(Correa & Adams, 1981; Honts & Amato,2007; Krapohl, Senter, & Stern, 2005). In thescreening context, the RI test may be suitableas an early screening tool in which theobjective is to investigate multiple relevanttopics. More data are needed to make strongstatements about the validity of the RI test inthescreeningsetting.However,newapproaches to computer-based data analysis(Kircher, Woltz, Bell, & Bernhardt, 1998) andtest automation (Honts & Amato, 2007) maywell raise the level of validity for the RI testsufficiently to make it a viable choice forscreening applications.The second family of deception tests,the CQT, uses relevant and irrelevantquestions similar to those used in theRelevant-Irrelevant test, but also includes athird type of question, the comparisonquestion. Comparison questions are designedto evoke responses from innocent individualsand to provide the innocent person a place tofocus one’s emotionality and attention. In theCQT an interaction is expected between thephysiological responses to question type(relevant and comparison) and guilt status.Guilty examinees are expected to producelarger physiological responses to relevantquestions than to comparison questions.Innocent examinees are expected to show theopposite pattern. There are many field testingformats that fall within the CQT category,most of which are named after the agency orsurname of their creator. In terms ofadministration, differences between CQTformats are trivial, mostly surroundingquestion ordering. The more important nontrivial differences between CQT formatsapplied in field practices concern theanalyses, and we return to those issues below.Readers interested in the differences betweenthe CQT variants are referred to Raskin andHonts (2002).There are two broad categories levant and the ComparisonQuestion Tests (CQT). The Relevant-Irrelevant(RI) test involves asking direct questions,known as relevant questions, about thematters to be assessed (e.g., Did you evercommit a serious crime?). The RI test alsocontainsseveralsimple,known-truthquestions that are usually answered truthfully(e.g., Are the lights on in this room?) known asirrelevant questions. The questions arerepeated several times while the examinee’sphysiology is monitored. The rationale of theRI test assumes that deceptive individuals willrespond with consistent and significantphysiological response to those questions towhich they are deceptive, whereas the truthfulexaminee will not show such responses. Ingeneral, the evaluation of RI polygraph examscalls for the examiner to make aninterpretation of what the terms consistentand significant mean while evaluating the test245Polygraph, 2009, 38(4)

Pre-Employment Polyg

Handler, Honts, Krapohl, Nelson & Griffin Integration of Pre-Employment Polygraph Screening into the Police Selection Process Mark Handler1, Charles R. Honts2, Donald J. Krapohl3, Raymond Nelson4, and Stephen Griffin5 Abstract The authors provide a polygraph primer for police psychologists involved in law enforcement personnel selection.