Transcription

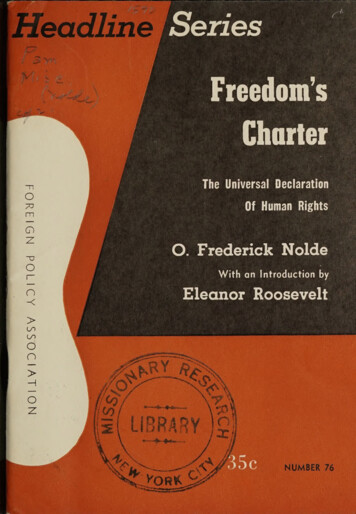

Freedom’sCharterFOREIGNThe Universal DeclarationOf Human Rightsj POLICYO. Frederick Nolde ;. i.W'r V’ With an Introduction byEleanor RooseveltASSOCIATIONv./NUMBER 76 ;v.

HEADLINE SERIESNumber 76July-August 1949IntroductionEleanor Roosevelt3Freedom’s CharterO. Frederick Nolde1.A World Goal52.Rebellion Against Tyranny83.Major Issues and Conflicts184.UN Activities265.Adoption of Declaration386.Next Steps49Declaration Text55

The AuthorsDr. O. Frederick Nolde:Dean of the Graduate School of theLutheran Theological Seminary at Philadelphia and director ofthe Commission of the Churches on International Affairs.Heattended the San Francisco Conference at which the UN Charterwas drafted as a consultant to the American delegation. He hassince served as consultant to the Economic and Social Council,attending every session of the Commission on Human Rights.Eleanor Roosevelt:United States delegate to the United Na tions General Assembly since its first session in London in Janu ary 1946.She also serves as American representative on theCommission on Human Rights and was elected chairman of theCommission in January 1947.HEADLINE SERIES, NO. 76, JULY 20, 1949, PUBLISHED BIMONTHLY BY THE FOREIGNPOLICY ASSOCIATION, INCORPORATED, 22 EAST 38TH STREET, NEW YORK 16, N. Y.WILLIAM W.COPIES, 35c.WADE,EDITOR.SUBSCRIPTION RATES 2.00 FOR6ISSUES.SINGLEENTERED AS SECOND CLASS MATTER AUGUST 19, 1943, AT THE POSTOFFICE AT NEW YORK, N. Y. UNDER THE ACT OF MARCH 3, 1879. COPYRIGHT, 1949,BY FOREIGN POLICY ASSOCIATION, INCORPORATED. PRODUCED UNDER UNION CONDITIONS AND COMPOSED, PRINTED, AND BOUND BY UNION LABOR. MANUFACTUREDIN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA,420

INTRODUCTIONThis article byDr. Nolde is a very clear and lucid statementwhich will give any one who reads it the story of the UniversalDeclaration of Human Rights. Dr. Nolde has attended almostevery session of the Commission on Human Rights. He is oneof the few observers representing nongovernmental organiza tions who attends as constantly as the delegates do.Because he is such a careful observer he sometimes gauges themood of the members more accurately than we ourselves do.I am glad that he says that:“Adequate appraisal (appraisal ofthe value of the Declaration) must wait for the perspective oftime.” It will be a long time before history will make its judg ment, and the judgment will depend, I think, on what thepeople of different nations do to make this document familiarto everyone.If they know it well enough, they will strive toattain some of the rights and freedoms set forth in it, and thateffort on their part is what will make it of value in clarifyingwhat was meant in the Charter in the references to human rightsand fundamental freedoms.In the last paragraph Dr. Nolde says: “The more widespreadobservance of human rights can ultimately ease the political3

tensions which now divide the world.” That is really the pointthe people of the world must remember.The observance ofhuman rights can be one of the foundation stones for peace,and I think that will emerge in reading this very interestingarticle.4

SEP 1 2 1949Freedom’s CharterbyO.Frederick Nolde1. A World GoalFor the first timein history, governments representing thegreater part of the world’s population have reached agreementon the broad definition of human rights and fundamental free doms. The United Nations, at the third session of the GeneralAssembly at Paris on December 10, 1948, formally adopted aUniversal Declaration of Human Rights by a vote of forty-eightin favor, none against and eight abstaining.The adoption of the Declaration comes at a time when thescope of international responsibility for protecting human rightsis being extensively and, at times, heatedly debated. This issuehas been prominent in the discussion of reported violations whichhave already been considered by the General Assembly and theEconomic and Social Council. What authority has the UnitedNations to intervene in the interest of a minority, as in the caseof Indians in the Union of South Africa? Does the Charter em power the General Assembly to take direct action when formallyconfronted by the apparent violation of freedom in Hungaryand Bulgaria?How far can the international organization goin initiating inquiry and remedial steps where a member state5

is accused of practicing forced labor?To what extent is theUnited Nations justified in acting when the U.S.S.R. preventsSoviet wives of foreign citizens from leaving their country withtheir husbands? Similar questions may be expected to arise when ever the United Nations is called upon to act—whether on viola tions reported to have occurred in totalitarian countries, incolonial territories, in the United Kingdom or in the UnitedStates.The important fact is that international action to protecthuman rights has not awaited clear definition of internationalresponsibility. The issue of human rights is located squarely inthe stream of human living. It is not merely academic. In thiscontext of human relations in a world society the Human RightsDeclaration was conceived, and in this context it must be under stood and applied.The Universal Declaration stands as the first part of a pro posed International Bill of Human Rights. In itself, it carriesno legal authority.It is to be followed by a Covenant, withMeasures of Implementation. The preamble of the Declarationcalls it “a common standard of achievement for all peoples andall nations, to the end that every individual and every organ ofsociety, keeping this Declaration constantly in mind, shall striveby teaching and education to promote respect for these rightsand freedoms . . . and to secure their universal and effectiverecognition and observance."Since the Declaration has no legally binding power, whatvalue can it have? Widely differing appraisals have already beengiven. Some people have taken a quite pessimistic attitude andare contending that the Declaration is nothing but empty words.Others enthusiastically claim that the mere adoption of it marksa significant milestone in history.Between these two extremesstands the vast multitude of people all over the world, whoseattitude has not yet fully taken shape.Adequate appraisal must await the perspective of time. Mean while, the Declaration is before us, an accomplished fact.6To

understand its immediate import and to set the stage for its mosteffective use now, we must view it in the framework of historywith particular attention to the recent developments which in fluenced its production.77

2. Rebellion Against TyrannyThe desire to havehis rights protected and observed is deeplyimbedded in the nature of man. The age-old struggle to achievethis end has run a checkered course. A glance over the centuriesreveals long periods where no substantial progress is evidentand where, in fact, men have been forced to submit to one formof tyranny or another. In such times man’s natural impulse tofreedom was curbed, but it did not disappear. Given favorablecircumstances, it found expression in new assertions of his rightsand in reinvigorated efforts to secure them. The charters, declara tions and bills which thus emerged captured the imagination ofpeople and became a rallying point for further struggle.Historic DocumentsThe achievements which stand out as significant in historywere gained almost always through rebellion against tyranny orresistance to threatened oppression. The British Magna Carta(1215), Petition of Rights (1628)and Bill of Rights(1689)developed from demands for the reform of particular abuses bygovernment. These documents were intended mainly to restrainthe king in his dealings with the powerful barons and churchleaders at whose insistence they were drawn.Ultimately theybrought benefit of liberty to all the people. The textual provi sions of the Magna Carta have little meaning for life today. Yetthis charter stands as a symbol of an historic struggle and of aspirit that lives on.8

ANOTHER STEPPINGSTONE'Dorman H. Smith for NEA ServiceThe French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citi zen was adopted by the revolutionary French National Assemblyin 1789. It is not a legislative enactment but rather a statementof principles to guide legislators and executives. It declares that“the end of all political association is the preservation of thenatural and imprescriptible rights of man.” Born in rebellion,it offers a strong and clear expression of the classical doctrine of9

natural rights. It has contributed much to spreading throughoutthe world the concept of essential and inalienable rights.American Safeguards for FreedomThe United States Declaration of Independence was the fore runner of the Constitution and of the Bill of Rights which ap pears mainly in the first ten amendments. The Bill of Rights(1791) was intended to provide protection for the people andthe states against the abuse of power by the newly formed centralgovernment. The adoption of the Fourteenth Amendment, pre scribing that “no state . . . shall deprive any person of life, liberty,or property, ivithout due process of law,” extended to state actionthe restraints which had been imposed on the federal government.It was the spirit of liberty which gave rise to such constitu tional safeguards—safeguards which could be vindicated in thecourts of the land. More important than the safeguards is thecontinued life of the spirit. For only through this living spiritcan freedom be preserved and made to apply to all men.The historic documents of liberty reflect the processes of ex tending the freedom of individuals to ever wider groups, of ex panding the content of freedom and of readjusting it to thenew needs resulting from changes in society. Only a few illus trations of significant landmarks have been given.In our owngeneration, the renewed emphasis upon human rights has beenin large degree a reaction against abuses.Motives which for merly prompted struggle, such as religious conviction or humani tarian concern, serve as partial incentives.But a new motivehas been added. As a result of recent events, men have becomeincreasingly convinced that the observance of human rightseverywhere is an imperative requirement for world peace andorder.Tyranny and oppression during the Second World War, par ticularly manifest in Germany and in the occupied countries,came to be regarded as a threat to liberty everywhere. In faceof this threat, leaders in the United Nations gave prominent10

STEPS TOWARD UN DECLARATIONNazi disregard for humanThe Four FreedomsJan. 6, 1941Atlantic CharterSan Francisco ConferenceApril25 -June26,194sAug.9-10,1941GRAPHIC ASSOCIATESplace to the human rights and freedoms which should be securedfor all men.Their pronouncements, which in numerous in stances won official approval, contributed to an atmosphere thatthe United Nations as an international organization could notsubsequently ignore.11

The Four FreedomsAddressing Congress on January 6, 1941, President Roosevelterected a cornerstone and offered a rallying-point in his nowfamous Four Freedoms:“We look forward to a world founded upon four essen tial human freedoms. The first is freedom of speech andexpression—everywhere in the world. The second is freedomof every person to worship God in his own way—everywherein the world. The third is freedom from want—which, trans lated into world terms, means economic understandingswhich will secure to every nation a healthy peaceful life forits inhabitants—everywhere in the world. The fourth isfreedom from fear—which, translated into world terms,means a world-wide reduction of armaments to such a pointand in such a thorough fashion that no nation will be in aposition to commit an act of physical aggression against anyneighbor—anywhere in the world.”The Atlantic Charter, signed by President Roosevelt andPrime Minister Churchill on August 14, 1941, included two ofthe Four Freedoms. Articles Six and Eight referred to “a peacewhich will afford to all nations the means of dwelling in safetywithin their own boundaries” and “the abandonment of the useof force.” Article Five recognized the “object of securing, forall, improved labor standards, economic advancement and socialsecurity.”Article Six concluded with the “assurance that allmen in all the lands may live out their lives in freedom fromfear and want.”In his report to Congress on the Atlantic Charter on August21, 1941, President Roosevelt indicated that his first two free doms were also implied:“It is also unnecessary for me to pointout that the declaration of principles includes of necessity theworld need for freedom of religion and freedom of information.No society of the world organized under the announced prin ciples could survive without these freedoms which are a part ofthe whole freedom for which we strive.”The announced goal to secure human rights to all men was12

formally incorporated in a joint declaration signed by the UnitedNations on January 1, 1942.The governments which becameparties to this declaration supported the provisions of the At lantic Charter, which however had included only two of theFour Freedoms. To remove any doubt concerning the intentionto include all essential freedoms, a general introductory state ment was incorporated in it:“Being convinced that completevictory over their enemies is essential to defend life, liberty, inde pendence and religious freedom, and to preserve human rightsand justice in their own lands as well as in other lands . . .”The strong emphasis upon human rights and freedoms whilethe war was in process gave rise to widespread insistence that anyorganization of nations to be erected following the war shouldaccept the protection of human rights as a major purpose.Human Rights in the UN CharterThe Dumbarton Oaks Proposals for the charter of a worldorganization contained only one brief and subordinate referenceto human rights and fundamental freedoms. In the period be tween October 1944, when the proposals were made public, andApril 1945, when the Conference on World Organization wasconvened at San Francisco, strong popular sentiment was arousedto remedy this defect. Accredited consultants to the United Statesdelegation—representing churches, labor, education, business andmany other interests—pressed for a more prominent recognitionof human rights and the establishment of a human rights com mission.Nongovernmentalorganizationscommunicated with their delegations.inothercountriesFrance, Canada, NewZealand, India, Egypt, Panama, Brazil, Uruguay, Cuba, Haiti,.Chile, San Domingo and Mexico submitted amendments con cerned with human rights.This flood of proposals influencedthe United States, the U.S.S.R., the United Kingdom and Chinato present separate or joint amendments which led to the textas finally adopted.The preamble of the Charter, written in the name of the13

peoples of the United Nations, expresses determination to “re affirm faith in fundamental human rights, in the dignity andworth of the human person, in the equal rights of men andwomen and of nations large and small.” One of the chief pur poses of the organization shall be “to achieve international co operation . in promoting and encouraging respect for humanrights and fundamental freedoms for all without distinction asto race, sex, language, or religion” (Art. 1, Sec. 3).The Charter relates this purpose to the functions and powersof the General Assembly (Art. 13, Sec. 1, b), and of the Eco nomic and Social Council (Art. 62, Sec. 2), and lists it amongthe basic objectives of the international Trusteeship System(Art. 76, Sec. c). The Economic and Social Council, empoweredto make recommendations for the purpose of promoting respectfor, and observance of, human rights and fundamental freedoms,is required “to set up commissions in economic and social fieldsand for the promotion of human rights” (Art. 68).New Factor IntroducedA new factor was here introduced into man’s age-old strugglefor freedom in society.The nations accepted an internationalresponsibility. The authority to recognize or deny man’s rightsand freedoms was traditionally vested in national states. Whenhuman rights were violated in any country, a foreign govern ment felt justified in intervening mainly to protect its nationals.In scattered instances, friendly representations were made toprotest extreme violations on grounds of common humanity.The Charter of the United Nations opens the way for actionbeyond diplomatic protection of citizens abroad or friendlyintervention in the name of humanity. Its terms are more in clusive than the Versailles provisions to protect minorities andthe objectives sought by the Mandates Commission of the Leagueof Nations or by the International Labor Organization.TheCharter seems to indicate that some kind of check is intended14

upon the constitutional and legal provisions as well as the prac tices of separate states.Unanswered QuestionsThe substantial progress noted in the United Nations Charteroffers ground for encouragement. At the same time, we mustrealistically admit that two important questions are left unan swered. These unanswered questions must be clearly understood,for the activities of the United Nations in the field of humanrights are directed toward finding the much needed solutions.First, what are the human rights which are to be respectedand observed? The Charter makes only broad reference to man’srights and freedoms. It does not specify any single right as toits substance or meaning. This general approach resulted fromthe reluctance of delegates at the San Francisco Conference tobecome ensnarled in a specification of particular rights.Ac cordingly, while the Charter brings into clear relief the fact thatthere are rights and freedoms, it in no sense contains a declara tion or bill of rights.While recognizing this inadequacy, we must give full creditto the emphasis upon the goal of observance “without distinc tion as to race, sex, language, or religion.”The standard ofnondiscrimination is commendable and marks a forward step.At the same time, unless accompanied by a definition of rights,it is open to abuse. This becomes readily apparent when onepictures what can happen in applying the principle of nondis crimination.Consider the illustration of religious liberty. All governmentsdo recognize man’s right to religious freedom. However, in theabsence of a definition of this right, they are free to place theirown construction upon it. They may hold that freedom of re ligion involves only freedom of worship in a limited form andthus deny the right of religious teaching and practice. They willobserve the terms of the Charter if they apply this conception15

“without distinction.” A similar situation could develop withrespect to the various social, civil and economic rights. The pro visions of the Charter will become effective in this regard onlywhen rights and freedoms have been specified and clearly defined.Means of PromotionSecond, by what means shall respect for and obsewance ofhuman rights be promoted? The Charter states that the UnitedNations shall seek to achieve international co-operation in pro moting and encouraging respect for and observance of humanrights and fundamental freedoms, but it does not specify themethods whereby this shall be done. The task of achieving inter national co-operation is assigned generally to the entire organi zation and more specifically to the General Assembly, the Eco nomic and Social Council and the Trusteeship System.So far as the Economic and Social Council is concerned, it isrequired to set up a Commission on Human Rights. Nowherein the Charter, however, is direct reference made to the mannerin which the United Nations or any organ is authorized to pro ceed in order that human rights may actually be exercised. Itseems quite clear, however, from various Charter references thatsteps can be taken to encourage member states to move towardthe accomplishment of this purpose.More baffling than the method of encouragement is the methodof action which the United Nations can undertake. The Charterauthorizes the United Nations—in most instances, the SecuritvCouncil—to take action in six types of situations which are un derstood to fall not within domestic but within internationaljurisdiction. These are:(1) an act of aggression; (2) a breachof the peace; (3) a threat to the peace; (4) a dispute, the con tinuance of which is likely to endanger the maintenance of inter national peace and security; (5) a situation which might lead tointernational friction or give rise to a dispute;(6) a questionrelating to the maintenance of peace and security, to armamentsor disarmament, or to general principles of co-operation.16

Action by the United Nations under these circumstances wasclearly designed in the interest of international peace and se curity. It may therefore be assumed that action on violations ofhuman rights will be possible under the Charter in the firstinstance when international issues are involved.What can be done by way of international action when viola tions do not constitute a threat to world peace or security is aquestion which the United Nations Charter does not answer.17

3. Major Issues and ConflictsThe activities ofthe United Nations with respect to humanrights have in the main been directed towards the two questionswhich its Charter left unanswered.In the course of its earlywork, the organization was forced to reckon with conflictingviews at many points. The issues thus raised must be understoodin order to appreciate the progress which the United Nationshas been able to make. Since the differences have not yet beenresolved on a world scale, they must be taken into account indetermining the steps that lie ahead.Meaning of Human RightsMost men agree that human rights should be respected andobserved. Disagreement begins to appear when they attempt tostate what man’s rights are and to determine the relative im portance to be attached to different rights. The tradition of theWestern societies lays particular stress upon the importance ofthe classical civil and social rights. These include equal protec tion before the law and the courts, individual liberty, freedomof conscience and religion, freedom of assembly and associationand freedom of speech and expression.Rights such as thesehave found expression in most constitutions and have been forti fied by legal provisions and by the insistent demand of popularopinion.Various factors have contributed to the conviction that, im18

portant as these rights are, they are not in themselves sufficient.People have found themselves victims of cycles of unemployment.Two world wars have completely disrupted national economies,with inevitable hardship upon large masses of the population.Even in normal times—if there be such—men living in an in*dustrial society know that without economic rights they can nolonger be free. In the Declaration of Santiago de Chile, adoptedby the governments of the American nations on September 16,1942, this new situation was described as follows:“To be ableto enjoy the basic freedoms of thought, expression and security,every man and woman must be afforded physical and economicprotection against social and economic risks through properlyorganized social action.”While there remain some people who refuse to recognize man’seconomic-social rights, it seems safe to assert that tacitly or openlythe importance of man’s economic freedom has come to be widelyaccepted.Considerable difference of opinion appears as to therelative importance to be attached to the traditional rights andthe newly emphasized economic rights.An extreme view is found in Soviet communism, where theright to work and the material well-being of people are declaredto be the primary consideration.In the United States, eventhough there are such provisions as unemployment insuranceand old-age benefits, there is a general disposition to considereconomic rights secondary, or certainly no more than on a parwith the traditional freedoms.Clash Over ObservanceEven more acute than the differing views as to the importanceof rights is the clash over the manner in which their observanceshall be achieved. The U.S.S.R. contends that the state by itscontrol and direct action is the responsible agent for seeing toit that the people enjoy their economic right. The operation ofthis principle results in a limitation upon the exercise of thetraditional freedoms. This is deemed no cause for disturbance,19

since the primary emphasis is placed upon the material well being of the people within the state.In other than Soviet-Communist countries, it is generally feltthat when the government assumes full responsibility for theobservance of economic rights, there is grave risk that the highlycherished traditional freedoms will be lost. In Great Britain andin some North European countries, a form of socialism, underwhich people maintain the right to change their government bypopular vote, represents an experiment in the method of in suring economic rights without loss of essential freedom.In the United States, where a variety of government controlshave been imposed upon management and labor and insuranceprovisions enacted, the major responsibilities for the exercise ofeconomic rights still rest with the people.Obviously the prob lem thus raised is one that has not been satisfactorily solved andmust be kept clearly to the fore. How can man’s economic rightsin an industrial society be insured without impairing the basicfreedoms which his nature and dignity demand?The Basis of Human RightsOn what grounds can man lay claim to rights and freedomsin society? In one sense, this is a theoretical question and mustbe answered largely from conviction.In another respect, how ever, it is a quite practical issue; for the answer which is acceptedwill determine in considerable measure the prerogative and au thority of the state.In the societies which gave birth to the classical declarationsof rights it was generally understood that the rights of the indi vidual are “anterior and superior” to the state.Man is a ra tional being and is entitled to everything that is essential to areasonable development of his personality. This view is variouslydefended on the basis of natural law or religious conviction. Itfinds its conclusion in the social or juridical contention that manhas inalienable rights.In a government which operates under a totalitarian system,20

Difficulties for International Actionl.Our ideas of Human Rights are different3 If "UN is to act what powers shall it have ?GRAPHIC ASSOCIATES

whether for political reasons or in the professed interests of thepeople, the individual becomes subordinate to the communityor to the state. He has no rights, it is claimed, other than thosewhich contribute apparently to community interest or whichthe state by its decision acknowledges are not harmful to thecommunity.In the final debate on the Universal Declaration of HumanRights at Paris, Andrei Y. Vishinsky, then Deputy Foreign Min ister of the U.S.S.R., said:“It is stated that the principle ofgovernment should not be dealt with in the Declaration ofHuman Rights because the Declaration is dealing with the rightsof human beings, of persons. Such a statement cannot be agreedto, because the rights of human beings cannot be consideredoutside the prerogatives of governments, and the very under standing of human rights is a governmental concept.”The seriousness of this difference becomes apparent both inthe process of defining human rights and in the process of seek ing their observance.If it is acknowledged that man by hisnature has inalienable rights, it follows that the state can dono more than recognize the existing rights and create conditionsfavorable to their exercise. If, on the other hand, it is claimedthat man has no inherent rights, the state can assume authorityunder changing times and conditions to decide what rights itshall grant to its people. With the authority to grant rights willobviously go the power to repudiate or deny rights. The pointof departure which is accepted as to the basis of human rightswill radically affect the manner in which the rights are definedand the provisions for securing them to all men.National or International Action?The United Nations is committed to achieve internationalco-operation in promoting and encouraging respect for humanrights and fundamental freedoms for all. To what extent do theprovisions of the Charter imply an international responsibility22

for the protection of the rights of individuals and groups? Howfar does that responsibility go?As a general limitation uponinternational action, the Charter, in Article 2, Section 7, states:“Nothing contained in the present Charter shall authorizethe United Nations to intervene in matters which are essen tially within the domestic jurisdiction of any state or shallrequire the Members to submit such matters to settlementunder the present Charter: but this principle shall not preju dice the application of enforcement measures under ChapterVII.” (Chapter VII sets forth action which the SecurityCouncil may take with respect to threats to the peace,breaches of the peace, and acts of aggression.)To what extent is protection of human rights a matter ofdomestic jurisdiction and to what extent a matter of interna tional concern?Wide Range of InterpretationsThe general nature of the Charter references has elicited awide range of interpretations. Very few people go so far as tocontend that the United Nations has clear authority over themanner in which human rights are construed and exercised inits member states.Many do claim, however, that the Charteropens the way for the United Nations progressively to achievesuch responsibility. 'They further contend that this developmentis imperative and that only as the nations yield a measure oftheir sovereignty can the goals of the Charter actually be realized.This view is not he

Rebellion Against Tyranny . 3. Major Issues and Conflicts . 4. UN Activities . 5. Adoption of Declaration . 6. Next Steps . Declaration Text . 3 5 . 8. 18 . 26 . 38 . 49 55 . The Authors . . It was the spirit of liberty which gave rise to such constitu tional safeguards—safeguards which could be vindicated in the courts of the land. More .