Transcription

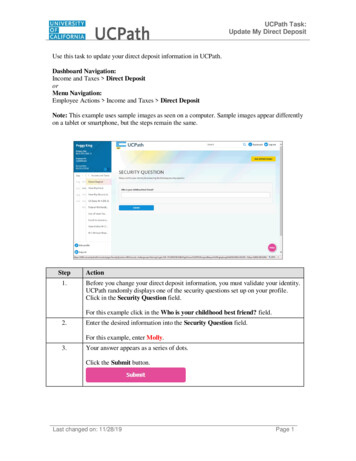

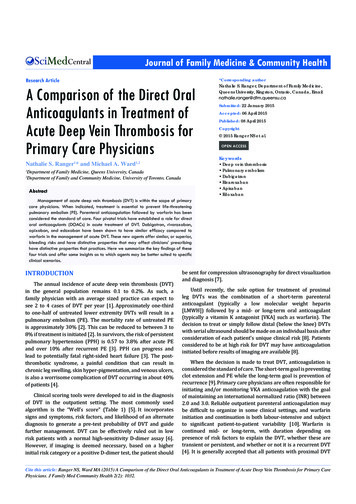

CentralJournal of Family Medicine & Community HealthResearch ArticleA Comparison of the Direct OralAnticoagulants in Treatment ofAcute Deep Vein Thrombosis forPrimary Care PhysiciansNathalie S. Ranger1* and Michael A. Ward1,2*Corresponding authorNathalie S. Ranger, Department of Family Medicine,Queens University, Kingston, Ontario, Canada, Email:Submitted: 22 January 2015Accepted: 06 April 2015Published: 08 April 2015Copyright 2015 Ranger NS et al.OPEN ACCESSKeywords Deep vein thrombosis Pulmonary embolism Dabigatran Rivaroxaban Apixaban Edoxaban1Department of Family Medicine, Queens University, Canada2Department of Family and Community Medicine, University of Toronto, CanadaAbstractManagement of acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT) is within the scope of primarycare physicians. When indicated, treatment is essential to prevent life-threateningpulmonary embolism (PE). Parenteral anticoagulation followed by warfarin has beenconsidered the standard of care. Four pivotal trials have established a role for directoral anticoagulants (DOACs) in acute treatment of DVT. Dabigatran, rivaroxaban,apixaban, and edoxaban have been shown to have similar efficacy compared towarfarin in the management of acute DVT. These new agents offer similar, or superior,bleeding risks and have distinctive properties that may affect clinicians’ prescribinghave distinctive properties that practices. Here we summarize the key findings of thesefour trials and offer some insights as to which agents may be better suited to specificclinical scenarios.INTRODUCTIONThe annual incidence of acute deep vein thrombosis (DVT)in the general population remains 0.1 to 0.2%. As such, afamily physician with an average sized practice can expect tosee 2 to 4 cases of DVT per year [1]. Approximately one-thirdto one-half of untreated lower extremity DVTs will result in apulmonary embolism (PE). The mortality rate of untreated PEis approximately 30% [2]. This can be reduced to between 3 to8% if treatment is initiated [2]. In survivors, the risk of persistentpulmonary hypertension (PPH) is 0.57 to 3.8% after acute PEand over 10% after recurrent PE [3]. PPH can progress andlead to potentially fatal right-sided heart failure [3]. The postthrombotic syndrome, a painful condition that can result inchronic leg swelling, skin hyper-pigmentation, and venous ulcers,is also a worrisome complication of DVT occurring in about 40%of patients [4].Clinical scoring tools were developed to aid in the diagnosisof DVT in the outpatient setting. The most commonly usedalgorithm is the “Well’s score” (Table 1) [5]. It incorporatessigns and symptoms, risk factors, and likelihood of an alternatediagnosis to generate a pre-test probability of DVT and guidefurther management. DVT can be effectively ruled out in lowrisk patients with a normal high-sensitivity D-dimer assay [6].However, if imaging is deemed necessary, based on a higherinitial risk category or a positive D-dimer test, the patient shouldbe sent for compression ultrasonography for direct visualizationand diagnosis [7].Until recently, the sole option for treatment of proximalleg DVTs was the combination of a short-term parenteralanticoagulant (typically a low molecular weight heparin[LMWH]) followed by a mid- or long-term oral anticoagulant(typically a vitamin K antagonist [VKA] such as warfarin). Thedecision to treat or simply follow distal (below the knee) DVTswith serial ultrasound should be made on an individual basis afterconsideration of each patient’s unique clinical risk [8]. Patientsconsidered to be at high risk for DVT may have anticoagulationinitiated before results of imaging are available [8].When the decision is made to treat DVT, anticoagulation isconsidered the standard of care. The short-term goal is preventingclot extension and PE while the long-term goal is prevention ofrecurrence [9]. Primary care physicians are often responsible forinitiating and/or monitoring VKA anticoagulation with the goalof maintaining an international normalized ratio (INR) between2.0 and 3.0. Reliable outpatient parenteral anticoagulation maybe difficult to organize in some clinical settings, and warfarininitiation and continuation is both labour-intensive and subjectto significant patient-to-patient variability [10]. Warfarin iscontinued mid- or long-term, with duration depending onpresence of risk factors to explain the DVT, whether these aretransient or persistent, and whether or not it is a recurrent DVT[4]. It is generally accepted that all patients with proximal DVTCite this article: Ranger NS, Ward MA (2015) A Comparison of the Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Treatment of Acute Deep Vein Thrombosis for Primary CarePhysicians. J Family Med Community Health 2(2): 1032.

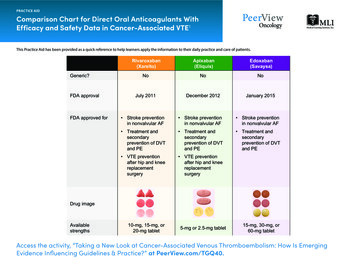

Ranger NS et al. (2015)Email:Centralshould be treated for a minimum of three months (‘mid-term’),with extension to at least six months (‘long-term’) if idiopathicDVT or active cancer and indefinite duration if it is a recurrentDVT (with annual re-assessment) [9].It is worthwhile noting that sparse randomized controlledtrial (RCT) evidence exists supporting the routine use ofanticoagulation in the treatment of acute DVT [11,12]. Indeedolder, small, underpowered trials found little difference inoutcome between non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs(NSAIDs), placebo, and anticoagulation in the management ofDVT/PE [11,12]. Evidence for warfarin’s effectiveness comesprimarily from older observational studies [11] showingdecreased risk of PE in treated versus untreated DVT and ourown collective historical clinical experience. Although onemight argue that the use of anticoagulation to treat DVT is notgrounded in rigorous RCT evidence, or that it is not clearly betterthan treatment with an NSAID (small underpowered trials), itis important to note that aspirin is not currently recommendedfor initial treatment of DVT. However, recent trials suggestthat aspirin can be considered for extended treatment of firstunprovoked DVT after completion of standard anticoagulanttherapy in patients where there exists clinical equipoise as towhether or not to extend treatment [13-15].Despite the seeming lack of RCT evidence, anticoagulationfor DVT remains the standard of care. A new class of medicationsknown as the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) – dabigatran[16], rivaroxaban [17], apixaban [18], and edoxaban [19] – haveemerged as new options for the treatment of acute DVT [19-22],extended DVT [19,22-24], and PE [19-22]. Regulatory agencieshave approved a direct thrombin inhibitor (dabigatran) andthree factor Xa inhibitors (rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban)[25] for the outpatient management of DVT; currently, edoxabanhas been approved in the United States but has not yet beenapproved for use in Canada or Europe.Most of the DOACs are associated with a reduction inclinically significant bleeding compared to warfarin and offer thebenefit of not requiring ongoing blood level monitoring [10]; thisrepresents a substantial increase in patient satisfaction and easeof use. Additionally, the new agents have significantly fewer druginteractions (Table 2). They are renally excreted at different ratesand require once or twice yearly monitoring of renal functiontests [26]. There remains some concern that no direct reversalagents are available at this time [10].The DOACs also have a rapid onset of action. Indeed apixabanand rivaroxaban were studied as stand-alone anticoagulantsand do not require the traditional bridging with a parenteralanticoagulant. This translates into an option for ‘oral-only’treatment of acute DVT, simplifying the treatment regimeconsiderably [10].Four landmark trials have been published comparing the novelDOACs to warfarin for the treatment of acute DVT. They weredesigned as non-inferiority studies (e.g. the DOAC demonstratingat least 50% of the proven efficacy of standard therapy) [27]. Wewill review the salient features of each of these trials and presentan unbiased view of the potential role of these new agents froma primary care perspective. We also encourage primary careclinicians to consider reviewing previously published analyseswritten from our specialist consultants’ perspectives [10,26,28].METHODSInclusion criteria for considering studies for thiscritical appraisalStudy design: Criteria for inclusion in this review included:1) published randomized controlled trials (RCTs) that comparedinterventions for treatment of acute VTE versus warfarin inadults (18 years of age or older), 2) trials must have usedrandomized allocation and single or double blinding, and 3)the results were to be presented using an intention-to-treat ormodified intention-to-treat analysis with a follow-up length ofthree to twelve months.The aim of this paper was to critically analyze the fourlandmark trials investigating DOAC use in acute DVT treatment.The literature search was completed to identify these trials inaddition to any outstanding comparable trials that warrantedinclusion.Table 1: Wells criteria for DVT.Clinical featureScoreActive cancer (treatment ongoing or within previous 6 months or palliative)1Recently bedridden for longer than three days or major surgery within the past four weeks1Paralysis, paresis, or recent orthopedic casting of a lower extremityLocalized tenderness in the deep vein systemSwelling of an entire legCalf swelling 3 cm greater than the other leg, measured 10 cm below the tibial tuberosityPitting edema greater in the symptomatic legCollateral non-varicose superficial veins111111Alternative diagnosis more likely than DVT (e.g. Baker's cyst, cellulitis, muscle damage, post phlebitic syndrome,-2inguinal lymphadenopathy, external venous compression) 0 low probability (3% prevalence of DVT)1-2 points moderate probability (17% prevalence of DVT)3-8 points high probability (75% prevalence of DVT)Adapted from Wells et al., 1997 [5].J Family Med Community Health 2(2): 1032 (2015)2/11

Ranger NS et al. (2015)Email:CentralTable 2: Drug interactions and contraindications to concomitant use of Apixaban[18]EdoxabanAdapted from Schulman, 2014 pinSt. John’s WortClarithromycinKetaconazoleRifampinSt. John’s nCarbamazepinePhenobarbitalKetoconazoleRifampinSt. John’s WortAzole akonazoleRitonavirRifampinSt. John’s Wort(See rivaroxaban)(See rivaroxaban)(Not yet approved in Canada or Europe; productmonograph not currently available in United States)(See rivaroxaban)Table 3: RE-COVER trial results: summary [20].Dabigatran150 mg BIDWarfarinDabigatran 150 mg BID vs.warfarin%%Hazard ratio (95% CI)P value1.40.87 (0.44-1.71)/VTE or related death2.42.1Symptomatic nonfatal PE1.00.6Symptomatic DVTDeath related to VTEMajor or clinically relevant non-majorbleedingMajor bleedingICHContraindication to Simultaneous Use1.30.15.61.600.28.81.90.21.10 (0.65-1.84)1.85 (0.74-4.64)0.33 (0.03-3.15)/// 0.001/0.690.82 (0.45-1.48)2.8Acute coronary syndrome0.40.2/All-cause mortality1.61.70.98 (0.53-1.79)Myocardial infarction/ Not reported0.3Outcome measureThe studies reviewed used a primary efficacy outcome of theincidence of recurrent symptomatic VTE (fatal or non-fatal PEand DVT) and/or death related to VTE [20]. The primary safetyoutcome was major bleeding (defined as overt and hemoglobinreduction of 20 g per liter or more, requiring 2 or more unitsof blood transfused, occurring at a critical site, or contributingto death) [20] and/or clinically relevant non-major bleeding(defined as overt bleeding not meeting criteria for major bleedingbut associated with medical intervention, assessment by aphysician, study drug interruption, or discomfort/impairment incompleting activities of daily living) [20].Exclusion criteriaRCTs that did not use warfarin as a comparator interventionJ Family Med Community Health 2(2): 1032 (2015)0.70.2/0.0024.23.1/0.63 (0.47-0.84)GI bleedDyspepsia 0.001/////were excluded. Studies published in a non-English language werealso excluded.Search methods for identification of studiesThe following databases were searched: PUBMED, MEDLINE,EMBASE, The Cochrane Library, and ClinicalTrials.gov.The PUBMED search was completed on October 6, 2014,updating a search that took place on May 20, 2014. It wassearched from 2004 to the present. The PUBMED search strategywas as follows: ((“new oral anticoagulants”) AND (“deep veinthrombosis”)). This search identified the following new oralanticoagulants as currently available for use: dabigatran,rivaroxaban, apixaban, and edoxaban (approved in the UnitedStates). The search strategy utilized the term “new oral3/11

Ranger NS et al. (2015)Email:CentralTable 4: EINSTEIN acute DVT trial results: summary [22].Recurrent VTEFatal PENonfatal PECombined first major or clinically relevantnon-major bleedingMajor bleedingClinically relevant non-major bleedingVascular eventsAll-cause mortality/ Not reportedRivaroxabanEnoxaparin-VKARivaroxaban vs. enoxaparin-VKA%%Hazard ratio (95% CI)P value0//2.13.01.21.00.068.10.87.30.72.2or PE. Importantly, all patients were initially given parenteralanticoagulation, for a mean duration of 10 days, before receivingexclusive treatment with dabigatran or warfarin. The primaryefficacy endpoints were time to recurrent symptomatic VTE and/or death related to VTE within 6 months after primary objectivediagnosis of symptomatic proximal DVT or PE. A total of 2564patients were randomized with 2539 included in a modifiedintention-to-treat analysis (patients who did not receive anystudy drug were excluded from analyses) and 27 were lost tofollow-up. Patients on warfarin were within the INR therapeuticrange (2.0 to 3.0) 60% of the time. A central committee, unawareof drug allocation, adjudicated all events. Trial outcomes aresummarized in table 3.Results of data collected during the study period showed arecurrence of VTE or death in 2.4% of patients on dabigatranversus 2.1% on warfarin (hazard ratio [HR] 1.10; 95% confidenceinterval [CI] 0.65-1.84; P 0.001), meeting requirements for noninferiority. A priori criteria for superiority were not reached.Major bleeding occurred in 1.6% of patients on dabigatran and1.9% on warfarin (HR 0.82, 95% CI 0.45-1.48). The authorssuggested that dabigatran 150 mg twice daily was as effective aswarfarin at reducing recurrent VTE risk, and was associated withequivalent risk of major bleeding and less non-major bleeding.There was no significant difference in rates of acute coronarysyndrome (ACS) or myocardial infarction (MI). An elevated riskof MI had been reported previously in the RE-LY trial [29]. Thistrial investigated dabigatran versus warfarin for prevention ofstroke or systemic embolism in patients with atrial fibrillationand an average CHADS score of 2.1. A subsequent meta-analysisof trials including dabigatran supported the finding of higher riskof MI, but also showed decreased all-cause mortality with thisagent [30]. This risk remains somewhat controversial and maybe, in part, explained by the known cardioprotective activity ofwarfarin [31].There was a trend towards a higher incidence ofgastrointestinal (GI) bleeding in the dabigatran group, as seen inthe RE-LY trial [29], but this did not reach statistical significance.Subjective complaints of dyspepsia were more frequentlyobserved in the dabigatran group than in the warfarin group,perhaps reflecting the acidic nature of the gut milieu as the drugis absorbed [29].J Family Med Community Health 2(2): 1032 (2015)8.10.68 (0.44-1.04)1.85 (0.74-4.64)0.97 (0.76-1.22) 0.001/0.771.20.65 (0.33-1.30)0.210.80.79 (0.36-1.71)0.557.02.9/0.67 (0.44-1.02)/0.06Dabigatran is currently approved for acute DVT treatment inCanada, the United States, and Europe.RivaroxabanRivaroxaban is an oral direct factor Xa inhibitor [17]. TheEINSTEIN-DVT trial [22] included two studies of rivaroxabanversus warfarin – the first arm examined treatment of acuteDVT while the second arm examined the continued treatmentof VTE. The first arm of this trial met inclusion criteria and willbe described here. The acute DVT study was a single-blind,open-label, event-driven, non-inferiority RCT comparing oralrivaroxaban only (15 mg twice daily for three weeks followed by20 mg once daily) for three, six, or twelve months versus standardtreatment with subcutaneous enoxaparin (1 mg/kg) followedby oral warfarin or acenocoumarol (both vitamin K antagonists[VKAs]). Enoxaparin was started within 48 hours of diagnosisand discontinued when the patient’s INR was greater than orequal to 2.0 for two consecutive days. All patients in the warfaringroup received a minimum of 5 days of parenteral enoxaparin.All participants had symptomatic DVT without symptomatic PE.Primary efficacy data were evaluated using an intention-totreat analysis. The primary efficacy outcome was symptomatic,recurrent VTE defined as the combination of DVT or nonfatalor fatal PE. The primary safety outcome, analyzed accordingto modified intention-to-treat, was clinically relevant bleedingdefined as the combination of major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding. A total of 3449 patients were enrolled with acompletion rate of 99.0% (33 lost to follow-up). Patients on aVKA were within the INR therapeutic range (2.0 to 3.0) 57.7%of the time. Central, blinded adjudication committees evaluatedall suspected outcome events. Trial outcomes are summarized intable 4.Patients in the rivaroxaban group developed symptomaticVTE recurrence totaling 2.1% versus 3.0% in the enoxaparin-VKAgroup (HR 0.68; 95% CI 0.44-1.04; P 0.001), establishing noninferiority of rivaroxaban. For the principal safety outcome, firstmajor or clinically relevant non-major bleeding occurred in 8.1%of patients on rivaroxaban versus 8.1% on standard therapy (HR0.97, 95% CI 0.76-1.22; P 0.77).The study’s authors suggested that rivaroxaban was aseffective as standard therapy for treatment of acute DVT, with4/11

Ranger NS et al. (2015)Email:Centrala similar safety profile (bleeding risk). Since this was an eventdriven study, the duration of treatment was shorter for 5.9% ofthe patients in the rivaroxaban group versus 5.5% of patients inthe standard therapy group. Total duration of treatment (three,six, or twelve months) for individual patients was determinedat the discretion of the treating physician, and there were nosignificant differences between numbers of patients in eachtreatment group.There were no increased vascular events or increased allcause mortality in the rivaroxaban group versus VKA group inthis study.Based on the results of this trial and other safety data [32],rivaroxaban was the first DOAC approved for acute treatment ofDVT in Europe, Canada, and the United States. It was also the firstexclusively oral treatment approved for VTE management untilvery recently [17,18].ApixabanApixaban is another oral factor Xa inhibitor [18]. TheAMPLIFY trial [21] was a double-blind, non-inferiority RCTcomparing apixaban 10 mg twice daily for seven days followedby 5 mg twice daily for six months versus standard treatment(subcutaneous enoxaparin 1 mg/kg twice daily followed byoral warfarin) in patients with symptomatic DVT and/or PE.Enoxaparin or placebo and injections were discontinued oncegiven for at least five days (median duration of 6.5 days) withwarfarin or placebo initiated concurrently and discontinuedwhen a blinded INR of 2.0 or greater was reached. Warfarin dosewas adjusted to a therapeutic INR between 2.0 to 3.0.Patients had objectively confirmed symptomatic proximalDVT or PE (with or without DVT). The primary efficacy outcomewas the adjudicated combination of incidence of recurrentsymptomatic VTE (nonfatal or fatal PE or DVT) or death relatedto VTE. The primary safety outcome was major bleeding (seedefinition in Methods section). The secondary safety outcomewas composite of major bleeding and clinically relevant nonTable 5: AMPLIFY trial results: summary [21].Recurrent VTE or VTE-related deathApixaban%2.3Fatal PE 0.1DVT only0.8Nonfatal PE (with or without DVT)1.0major bleeding. If non-inferiority was reached with respect to theprimary efficacy outcome, an a priori decision had been made totest for superiority according to a pre-specified order: primarysafety outcome, primary efficacy outcome, and secondary safetyoutcome. A total of 5400 patients were randomized with 5395included in the intention-to-treat analysis (five excluded due toabsent source documentation) and 28 were lost to follow-up.Patients on warfarin were within the INR therapeutic range (2.0to 3.0) 61% of the time. An independent, blinded committeeadjudicated all suspected outcome events. Trial outcomes aresummarized in table 5.Results demonstrated a recurrence of symptomatic VTE orVTE-related death in 2.3% of patients on apixaban versus 2.7%on enoxaparin-warfarin (RR 0.84; 95% CI 0.60-1.18; P 0.001),indicating non-inferiority of apixaban. In terms of the principalsafety outcome, major bleeding occurred in 0.6% of patients onapixaban versus 1.8% on standard therapy (RR 0.31, 95% CI0.17-0.55; P 0.001) and met requirements for superiority.The study’s authors suggested that oral apixaban alone wasas effective as standard therapy to prevent VTE recurrence;furthermore, apixaban was deemed to have a superior safetyprofile with regards to major bleeding.The authors also assessed whether efficacy of apixabandiffered depending on VTE presentation (i.e. PE, limited DVT orextensive DVT) and reported that efficacy was similar amongstthese groups.Apixaban has recently been approved for the management ofacute VTE and prevention of recurrent DVT and PE in the UnitedStates, Europe and Canada [18].EdoxabanEdoxaban is the third oral factor Xa inhibitor studied for VTEmanagement [19]. The Hokusai-VTE trial [19] was a double-blind,double-dummy, event-driven non-inferiority RCT examiningedoxaban 60 mg once daily versus warfarin in patients withEnoxaparin-warfarin Apixaban vs. enoxaparin-warfarin%Relative risk (95% CI)P value0.1//2.70.91.30.84 (0.60-1.18) 0.001////Major bleeding0.61.80.31 (0.17-0.55) 0.001*GI bleed0.30.7//ICHCombined major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleedingClinically relevant non-major bleedingMIAll-cause mortality*P-value for superiority/ Not reportedJ Family Med Community Health 2(2): 1032 (2015)0.14.33.80.21.50.29.7/0.44 (0.36-0.55) 0.001//8.00.48 (0.38-0.60)1.90.79 (0.53-1.19)0.1///5/11

Ranger NS et al. (2015)Email:Centralanticoagulants” rather than “direct oral anticoagulants” to reflectthe longer duration of use of the former term.The Ovid MEDLINE search was completed on September7, 2014. It was searched from 1996 to the present. TheMEDLINE search strategy was as follows: ((“Administration,Oral”[Mesh]) AND (“Anticoagulants”[Mesh]) AND (“VenousThromboembolism” [Mesh])).The EMBASE search was completed on October 6, 2014.It was searched from 1980 to the present. The search strategywas as follows: ((“dabigatran/ct AND dabigatran/po [ClinicalTrial,Oral Drug Administration]” [Mesh]) AND (venousthromboembolism/ OR deep vein thrombosis/ OR lowerextremity deep vein thrombosis/ OR upper extremity deep veinthrombosis/” [Mesh])). Three more searches were completedusing the identical search terms but each replaced “dabigatran”with “rivaroxaban,” “apixaban,” or “edoxaban,” respectively.The Cochrane Library search was completed on October6, 2014. It was searched from 2004 to the present. The searchstrategy was as follows: ((“dabigatran”) AND (“deep veinthrombosis”)). Three more searches were completed usingthe identical search terms but each replaced “dabigatran” with“rivaroxaban,” “apixaban,” or “edoxaban,” respectively.The ClinicalTrials.gov search was completed on OctoberTable 6: Hokusai-VTE trial results: summary [19].Recurrent VTE or VTE-related death(while on treatment)Fatal PE (during overall study period)Nonfatal PE with or without DVT (duringoverall study period)Combined first major or clinically relevantnon-major bleedingMajor bleedFatal ICHNonfatal ICH6, 2014. It was searched from its start date to the present. Thesearch strategy was as follows: ((“dabigatran”) AND (“deepvein thrombosis”)). Three more searches were completed usingthe identical search terms but each replaced “dabigatran” with“rivaroxaban,” “apixaban,” or “edoxaban,” respectively.Data collection and analysisA total of 213 articles were found. Each full text article wasexamined according to the criteria for review (see ‘Inclusioncriteria for considering studies for this critical appraisal’ and‘Exclusion criteria’). The article was read in its entirety or untilexclusion criteria were met. Articles were included if theypresented a robust RCT of an intervention to treat acute DVTusing a direct oral anticoagulant in comparison to standardtreatment and reported both primary efficacy and safetyoutcomes. Required duration of follow-up was at least three totwelve months.RESULTSDabigatranDabigatran is an oral direct factor IIa (thrombin) inhibitor[16]. The RE-COVER trial [20] was a double-blind, double-dummynon-inferiority RCT of oral dabigatran (150 mg twice daily)versus oral warfarin in patients with symptomatic DVT and/EdoxabanHeparin-warfarinEdoxaban vs. heparin-warfarin%%Hazard ratio (95% CI)0.1/1.61.91.21.40.100.1/1.60.3 0.1 0.1ACS0.50.37.23.2/ Not reported/0.81 (0.71-0.94)GI bleedingAll-cause mortality/10.30.1Clinically relevant non-major bleeding0.82 (0.60-1.14)8.51.4P value 0.001 (for noninferiority)0.84 (0.59-1.21)//8.90.80 (0.68-0.93)3.1///0.004 (forsuperiority)0.35 (forsuperiority)///0.004 (forsuperiority)//Table 7: Summary of conclusions from individual landmark RCTs of Y[21]J Family Med Community Health 2(2): 1032 (2015)ConclusionEfficacy: non-inferior to standard therapySafety: similar safety profile (equivalent risk of major bleeding and less non-major bleeding)Efficacy: non-inferior to standard therapySafety: similar safety profile (with respect to overall bleeding risk)Efficacy: non-inferior to standard therapySafety: superior (significantly less major bleeding)Efficacy: non-inferior to standard therapySafety: similar safety profile (major bleeding), but superior for overall bleeding risk6/11

Ranger NS et al. (2015)Email:Centralsymptomatic DVT and/or PE. Both groups received parenteralanticoagulation initially, with either open-label enoxaparin orunfractionated heparin (UFH) daily for at least five days (medianduration of 7 days). Edoxaban or placebo was started afterdiscontinuation of the parenteral anticoagulant (edoxaban wasgiven as a 30 mg once daily dose if the patient had a creatinineclearance of 30 to 50 mL per minute, body weight of 60 kg or less,or if taking a potent P-glycoprotein inhibitor medication). In theedoxaban and warfarin groups, 17.8% and 17.4% of patients tookthe 30 mg dose, respectively. Warfarin or placebo was initiatedconcurrently with heparin and discontinued when a blinded INRof 2.0 or greater was reached. Warfarin dose was adjusted to atherapeutic INR between 2.0 to 3.0. Treatment was completedfor a minimum of three months and maximum of twelve months,with duration at the discretion of the treating physician. Patientswere contacted every three months after discontinuing the studydrug and all patients were contacted at month 12, regardlessof their actual duration of treatment. The overall study periodwas considered to be twelve months. The primary efficacyoutcome was the adjudicated combination of time to recurrenceof symptomatic VTE (nonfatal or fatal PE or DVT) or deathrelated to VTE. The primary safety outcome was the incidenceof adjudicated clinically relevant bleeding (composite of majorbleeding and clinically relevant non-major bleeding). A total of8292 patients were randomized with 8240 patients included inthe modified intention-to-treat analysis (including 11 patientslost to follow-up), as patients who did not receive any studydrug were excluded from analyses. Patients on warfarin werewithin the INR therapeutic range (2.0 to 3.0) 63.5% of the time.An independent, blinded committee adjudicated all suspectedoutcome events. Trial outcomes are summarized in (Table6).Recurrent VTE or VTE-related death occurred in 1.6%of patients on edoxaban compared to 1.9% of patients onwarfarin (HR 0.82; 95% CI 0.60-1.14; P 0.001), establishingnon-inferiority of edoxaban. With regards to the primary safetyoutcome, the composite of first major or clinically relevant nonmajor bleeding occurred in 8.5% of patients on edoxaban versus10.3% on warfarin (RR 0.81, 95% CI 0.71-0.94; P 0.004) andmet requirements for superiority. It was suggested that oraledoxaban, preceded by enoxaparin or UFH, was as effective asstandard therapy to prevent VTE recurrence with better safetyoutcomes regarding bleeding.The authors noted that efficacy of edoxaban was preservedregardless of whether patients initially presented with PE,limited DVT, or extensive DVT. They also observed recurrencerates during the overall study period when some patients were nolonger receiving medication, and found that edoxaban remainednon-inferior to standard therapy.At this time, edoxaban is approved in Japan and the UnitedStates for the treatment and prevention of recurrent VTE [25],but is still awaiting approval in Canada and Europe.DISCUSSIONThe completion of these four landmark trials providesconvincing evidence that DOACs can be considered as a first-Table 8: Summary of DOAC dosing and characteristics to consider before prescribing.InitialHeparin Use ContraindicationsRequiredMechanical heart valveActive bleeding or high riskSevere renal impairmentRECOVER150 mg BIDYesConcurrent use of other anticoagulantsDabigatran[16]Concurrent use of drugs that are strong inhibitors of P-glycoprotein (P-gp)Pregnancy/lactation 18 years oldMechanical heart valveActive bleeding or high riskSevere renal impairment15 mg BID x 21Concurrent use of other anticoagulants[17

Ranger NS, Ward MA (2015) A Comparison of the Direct Oral Anticoagulants in Treatment of Acute Deep Vein Thrombosis for Primary Care . Physicians. J Family Med Community Health 2(2): 1032. . A new class of medications known as the direct oral anticoagulants (DOACs) - dabigatran [16], rivaroxaban [17], apixaban [18],and edoxaban [19] - have