Transcription

United States General Accounting OfficeGAOReport to the Chairman, Committee onGovernment Reform, House ofRepresentativesMay 2004HOMELANDSECURITYManagement of FirstResponder Grants inthe National CapitalRegion Reflects theNeed for CoordinatedPlanning andPerformance GoalsGAO-04-433

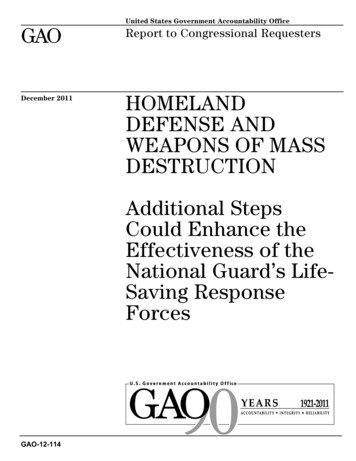

May 2004HOMELAND SECURITYHighlights of GAO-04-433, a report to theChairman, Committee on GovernmentReform, House of RepresentativesSince the tragic events ofSeptember 11, 2001, the NationalCapital Region (NCR), comprisingjurisdictions including the Districtof Columbia and surroundingjurisdictions in Maryland andVirginia, has been recognized as asignificant potential target forterrorism. GAO was asked toreport on (1) what federal fundshave been allocated to NCRjurisdictions for emergencypreparedness; (2) what challengesexist within NCR to organizing andimplementing efficient andeffective regional preparednessprograms; (3) what gaps, if any,remain in the emergencypreparedness of NCR; and (4) whathas been the role of theDepartment of Homeland Security(DHS) in NCR to date.GAO recommends that theSecretary of DHS (1) work withlocal NCR jurisdictions to developa coordinated strategic plan toestablish capacity enhancementgoals and priorities; (2) monitor theplan’s implementation; and(3) identify and address gaps inemergency preparedness andevaluate the effectiveness ofexpenditures by conductingassessments based on establishedstandards and guidelines.Management of First Responder Grants inthe National Capital Region Reflects theNeed for Coordinated Planning andPerformance GoalsIn fiscal years 2002 and 2003, grant programs administered by theDepartments of Homeland Security, Health and Human Services, and Justiceawarded about 340 million to eight NCR jurisdictions to enhanceemergency preparedness. Of this total, the Office for National Capital RegionCoordination (ONCRC) targeted all of the 60.5 million Urban Area SecurityInitiative funds for projects designed to benefit NCR as a whole. However,there was no coordinated regionwide plan for spending the remaining funds(about 279.5 million). Local jurisdictions determined the spending prioritiesfor these funds and reported using them for emergency communications andpersonal protective equipment and other purchases.NCR faces several challenges in organizing and implementing efficient andeffective regional preparedness programs, including the lack of acoordinated strategic plan for enhancing NCR preparedness, performancestandards, and a reliable, central source of data on funds available and thepurposes for which they were spent.Without these basic elements, it is difficult to assess first respondercapacities, identify first responder funding priorities for NCR, and evaluatethe effectiveness of the use of federal funds in enhancing first respondercapacities and preparedness in a way that maximizes their effectiveness inimproving homeland security.National Capital Region JurisdictionsMontgomery CountyDistrict ofColumbiaCity of AlexandriaFairfax CountyDHS and the ONCRC Senior PolicyGroup generally agreed with GAO’srecommendations and noted that anew governance structure, adoptedin February 2004, shouldaccomplish essential .To view the full product, including the scopeand methodology, click on the link above.For more information, contact William O.Jenkins, Jr., at (202) 512-8757 orjenkinswo@gao.gov.ArlingtonCountyLoudoun CountyPrince WilliamCountyVirginiaMarylandSource: National Capital Planning Commission.Prince George'sCounty

ContentsLetter1Results in BriefBackgroundMultiple Grants Support a Wide Variety of Uses, IncludingEquipment, Training and Exercises, Planning, and BioterrorismPreparednessChallenges to Effective Grants Management Include Lack ofStandards, Planning, and DataAssessing the Remaining Gaps in NCR is Difficult withoutGuidance, Reliable Data, or AnalysisDHS and ONCRC Appear to Have Had a Limited Role in PromotingRegional Coordination in NCRConclusionsRecommendations for Executive ActionAgency Comments and Our Evaluation3613233435363737Appendix IScope and Methodology40Appendix IINCR Jurisdictions’ Arrangements to Respond toPublic Safety Emergencies42Regional Bodies Facilitate Coordination Efforts in Other AreasMutual Aid Agreements Are in Place within NCR4243Comments from the Department of HomelandSecurity45Appendix IIIAppendix IVComments from the National Capital Region’s SeniorPolicy Group47Appendix VGAO Contacts and Staff Acknowledgments53GAO ContactsStaff Acknowledgments5353Page iGAO-04-433 Homeland Security

TablesTable 1: Characteristics of National Capital Region JurisdictionsTable 2: Selected Emergency Preparedness Funding Sources toNCR Jurisdictions in Fiscal Years 2002 and 2003Table 3: Uses of Selected Homeland Security Grant ProgramsTable 4: Major Items Funded by NCR Jurisdictions from FiscalYear 2002 DOD Emergency Supplemental AppropriationTable 5: Uses of NCR Urban Area Security Initiative Funds1214172022FigureFigure 1: National Capital Region OGWMDPage iiCapital Wireless Integrated NetworkCitizens Emergency Response TrainingCatalogue of Federal Domestic AssistanceU.S. Department of Homeland SecurityDepartment of DefenseEmergency Management Performance Grant ProgramDHS’s Federal Emergency Management AgencyU.S. Department of Health and Human ServicesMaryland Emergency Management AgencyNational Capital RegionNorthern Virginia Regional CommissionDHS’s Office for Domestic PreparednessDHS’s Office of National Capital Region CoordinationRegional Emergency Coordination PlanRegional Incident Communication and CoordinationSystemUrban Area Security InitiativeVirginia Department of Emergency ManagementWashington Metropolitan Council of GovernmentsWeapons of Mass DestructionGAO-04-433 Homeland Security

This is a work of the U.S. government and is not subject to copyright protection in theUnited States. It may be reproduced and distributed in its entirety without furtherpermission from GAO. However, because this work may contain copyrighted images orother material, permission from the copyright holder may be necessary if you wish toreproduce this material separately.Page iiiGAO-04-433 Homeland Security

United States General Accounting OfficeWashington, DC 20548May 28, 2004The Honorable Tom DavisChairmanCommittee on Government ReformHouse of RepresentativesDear Mr. Chairman:Since the tragic events of September 11, 2001, the Washington, D.C., area,known as the National Capital Region (NCR), has been recognized as ahigh-threat area for terrorism.1 The complexity of the region, composed ofjurisdictions including the nation’s capital and surrounding areas in thestates of Maryland and Virginia, and a range of potential targets, presentssignificant challenges to coordinating and developing effective homelandsecurity programs. In recognition of the region’s status as a significantpotential target, a substantial amount of federal funding was provided toNCR in fiscal years 2002 and 2003 to enhance the region’s ability toprepare for and respond to emergencies, including terrorist attacks.Federal funding has also been provided to other high-threat urban areasaround the nation, and at your request, our work in NCR will be followedby a review of coordination practices in several other urban regionsaround the nation.In 2003, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) was established toconsolidate the resources of 22 federal agencies for dealing in amultifaceted and comprehensive manner with domestic preparedness,including coordinating with other levels of government, planningprograms, and assessing their effectiveness. These responsibilities includeoversight of the grant-making process to promote effective domesticpreparedness programs. Appropriations to DHS and agencies in theDepartments of Justice and Health and Human Services for domesticpreparedness programs for state and local governments totaled nearly1The Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P.L. 107-296, §882 (2002)) incorporates the followingdefinition of the National Capital Region from 10 U.S.C. 2674 (f)(2). It is a geographic areathat consists of the District of Columbia; Montgomery and Prince George’s Counties inMaryland; Arlington, Fairfax, Loudoun, and Prince William Counties and the City ofAlexandria in Virginia; and all cities and other units of government within the geographicareas of such district, counties, and city. We focused on the eight largest jurisdictions.Page 1GAO-04-433 Homeland Security

13.9 billion in fiscal years 2002 and 2003. These grants include funding toNCR, which received special focus with the creation of the Office forNational Capital Region Coordination (ONCRC) in statute as part of thenew department. ONCRC was established to oversee and coordinatefederal programs for, and relationships with, state, local, and regionalauthorities. ONCRC’s statutory responsibilities also include assessingneeds, providing information and support, and facilitating access tofederal domestic preparedness grants and related programs. To assist inaccomplishing its mission, ONCRC developed a governance structure toreceive input from state and local authorities through a Senior PolicyGroup composed of representatives designated by the Governors ofMaryland and Virginia and the Mayor of the District of Columbia.You asked us to examine preparedness efforts in NCR, with an emphasison the use of funds, what has been done recently to better position thearea to address potential threats, and what continuing problems exist inorganizing and implementing efficient regional programs. This reportaddresses the following questions: What federal funds have been allocated to local jurisdictions in the NCRfor emergency preparedness, for what specific purposes, and from whatsources? What challenges exist within NCR to organizing and implementingefficient and effective regional preparedness programs? What gaps, if any, remain in the emergency preparedness of NCR? What has been DHS’s role to date in enhancing the preparedness of NCRthrough such actions as coordinating the use of federal emergencypreparedness grants, assessing preparedness, providing guidance,targeting funds to enhance preparedness, and monitoring the use of thosefunds?To respond to the questions, we met with and obtained documentation ongrant awards and spending plans from officials of DHS, the MetropolitanWashington Council of Governments, ONCRC Senior Policy Group, stateemergency management agencies, and first responder officials from NCRjurisdictions. We identified 25 emergency preparedness programs thatprovided funding to NCR, and we selected 16 of them for our detailedreview. These 16 grants were selected to cover a range of programsincluding the largest funding sources; grants provided for generalpurposes, such as equipment and training; and grants provided for specificPage 2GAO-04-433 Homeland Security

purposes, such as fire prevention and bioterrorism. We collected andanalyzed grant data from federal, state, and local sources. We alsoreviewed relevant reports, studies, and guidelines on homeland securityand domestic preparedness. We conducted our review from June2003 through February 2004 in accordance with generally acceptedgovernment auditing standards. See appendix I for more details on ourscope and methodology.Results in BriefIn fiscal years 2002 and 2003, NCR received a total of about 340 millionfrom 16 grants administered by the Departments of Homeland Security,Health and Human Services, and Justice. These grants were awarded tostate and local emergency management, law enforcement, firedepartments, and other emergency response agencies in the NationalCapital Region to enhance their ability to prepare for and respond toemergencies, including terrorist incidents. Within NCR, two fundingsources—the Fiscal Year 2002 Department of Defense EmergencySupplemental Appropriation (almost 230 million) and the Urban AreaSecurity Initiative (UASI) ( 60.5 million)—accounted for 85 percent of thehomeland security grant funds awarded. These two sources were used forsimilar purposes. Funds from the Fiscal Year 2002 Department of DefenseEmergency Supplemental went directly to local jurisdictions that haddiscretion to use it for their own priorities and needs. NCR jurisdictionsreported they used these funds to purchase a range of equipment, supplies,training, and technical assistance services. The major expendituresreported were mostly for communications systems, including aninteroperable radio system, and other types of equipment, such asequipment for emergency operations centers, bomb squad materials, bombsquad and command vehicles, and a mass casualty and disaster unit.ONCRC developed a plan for the use of funds from UASI, the purpose ofwhich was to enhance security in large urban areas. The plan for thesefunds identified activities that would benefit the region as a whole,including equipment ( 26.5 million), planning ( 12.4 million), the costs ofhigher threat alert levels ( 10.6 million), training ( 5.2 million), exercises( 4 million), and administrative costs ( 1.8 million).ONCRC and NCR face at least three interrelated challenges in managingfederal funds in a way that maximizes the increase in first respondercapacities and preparedness while also minimizing inefficiency andunnecessary duplication of expenditures. First, and most fundamental, isthe lack of preparedness standards that could be used to assess existingfirst responder capacities, identify gaps in those capacities, and measureprogress in achieving specific performance goals. Such standards wouldPage 3GAO-04-433 Homeland Security

include functional standards for equipment, such as personal protectionsuits; performance standards, such as the number of persons per hour thatcould be decontaminated after a chemical attack; and perhaps bestpractice benchmarks. DHS administered the Office for DomesticPreparedness (ODP) Assessment to NCR jurisdictions in the summer of2003. However, the lack of performance standards makes it difficult to usethe results of the assessment to identify the most critical gaps incapacities. Since the NCR jurisdictions completed their ODP assessments,DHS has taken steps to address this challenge by adopting its first set offunctional standards for protective equipment and making reference toestablishing a system of national standards in its recently releasedstrategic plan.Second, there is no coordinated regionwide plan for establishing firstresponder performance goals, needs, and priorities and assessing thebenefits of expenditures to enhance first responder capabilities. Prior toSeptember 11, there were some efforts to develop regional emergencyresponse planning and coordination, such as mutual aid agreementsamong neighboring jurisdictions. Since that time, the Washington Councilof Governments (WashCOG) has developed one of the first regionalemergency coordination plans and a communications notification systemfor NCR. However, no such NCR-wide coordination methods have beendeveloped for guiding the spending of federal grant dollars and assessingtheir effects on enhancing first responder capacities and preparedness.Individual jurisdictions and their emergency response agencies havedetermined how the majority ( 279.5 million) of the approximately 340 million in federal grant funds will be spent. The one exception is thefunding for UASI ( 60.5 million). ONCRC has focused its initialcoordination efforts on developing a regional plan for the use of UASIfunds for projects to benefit NCR as a whole.Third, there is no readily available, reliable source of information on theamount of first responder federal grant funds available to each NCRjurisdiction, the budget plans and criteria used to determine spendingpriorities, and actual expenditures. While the NCR jurisdictions arerequired to submit separate reports on each grant to the administeringfederal agency, ONCRC has not obtained or consolidated this informationto develop a comprehensive source of information for NCR on grantsreceived, plans and priorities for spending those funds, and actualexpenditures. Generally, spending decisions were made on a grant-bygrant basis and were largely in response to first responder and emergencymanagement officials’ requests for specific expenditures. WithoutPage 4GAO-04-433 Homeland Security

consistently available, reliable data, it is difficult to verify the results ofODP’s assessment and establish a baseline that could then be used todevelop plans to address outstanding needs.During our review, we also could identify no reliable data on preparednessgaps in NCR, which of those gaps were most important, and the status ofefforts to close those gaps. This is because the baseline data needed toassess those gaps had not been fully developed or made available on aNCR-wide basis, and ONCRC does not have information on how localjurisdictions have used federal grant monies to enhance their capacity andpreparedness. Consequently, it is difficult for us or ONCRC to determinewhat gaps, if any, remain in the emergency response capacities andpreparedness within NCR. Were these data available, the lack of standardsagainst which to evaluate them would make it difficult to assess gaps. TheODP assessment did, however, collect information on regional securityrisks and needs for the NCR jurisdictions. ONCRC based spendingdecisions for UASI funds on the results of the assessment, with the fundsused only for regional needs. On the other hand, officials in several NCRjurisdictions said that they have not received any feedback on the resultsof the assessment for their individual jurisdictions. It is not clear how theregional assessment and UASI spending plan links to the use of othergrants for local jurisdictions and the gaps the jurisdictions’ spending isdesigned to address.To date, DHS and ONCRC appear to have had a limited role in assessingand analyzing first responder needs in NCR and developing a coordinatedeffort to address those needs through the use of federal grant funds.Without an NCR baseline on emergency preparedness, a plan forprioritizing expenditures and assessing their benefits, and reliableinformation on funds available and spent on first responder needs in NCR,it is difficult for ONCRC to fulfill its statutory responsibility to oversee andcoordinate federal programs and domestic preparedness initiatives forstate, local, and regional authorities in NCR. Some officials within NCRgenerally believed that additional DHS guidance also is needed on likelyemergency scenarios for which to prepare and how to prepare for them. Inmeetings with us, the former Director of ONCRC acknowledged that theoffice could consider coordinating expenditures for federal grants otherthan the UASI grant. He also said that consistent records and a centralsource of information on NCR emergency responder grants would assistONCRC in fulfilling its responsibilities.Because of the importance of preparing NCR and other high-risk areas tomeet considerable homeland security challenges, we are recommendingPage 5GAO-04-433 Homeland Security

that the Secretary of DHS (1) work with NCR jurisdictions to develop acoordinated strategic plan to establish first responder enhancement goalsand priorities that can be used to guide the use of federal emergencypreparedness funds; (2) monitor the plan’s implementation to ensurefunds are used in a way that promotes effective expenditures that are notunnecessarily duplicative; and (3) identify and address gaps in emergencypreparedness and evaluate the effectiveness of expenditures in meetingthose needs by adapting standards and preparedness guidelines based onlikely scenarios for NCR and conducting assessments based on them.We provided a draft of this report to the Secretary of DHS and to NCR’sSenior Policy Group for comment. DHS and the Senior Policy Groupgenerally agreed with our recommendations, but also stated that NCRjurisdictions had worked cooperatively together to identify opportunitiesfor synergies and lay a foundation for meeting the challenges noted in thereport. DHS and the Senior Policy Group also agreed that there is a needto continue to improve preparedness by developing more specific andimproved preparedness standards, clearer performance goals, and animproved method for tracking regional initiatives. DHS noted that a newgovernance structure, adopted in February 2004, should accomplishessential regionwide coordination.BackgroundSince September 11, 2001, there has been broad acknowledgment by thefederal government, state and local governments, and a range ofindependent research organizations of the need for a coordinatedintergovernmental approach to allocating the nation’s resources toaddress the threat of terrorism and improve our security. This coordinatedapproach includes developing national guidelines and standards andmonitoring and assessing preparedness against those standards toeffectively manage risk. The National Strategy for Homeland Security(National Strategy), released in 2002 following the proposal for DHS,emphasized a shared national responsibility for security involving closecooperation among all levels of government and acknowledged thecomplexity of developing a coordinated approach within our federalsystem of government and among a broad range of organizations andinstitutions involved in homeland security. The national strategyhighlighted the challenge of developing complementary systems that avoidunintended duplication and increase collaboration and coordination sothat public and private resources are better aligned for homeland security.The national strategy established a framework for this approach byidentifying critical mission areas with intergovernmental initiatives in eacharea. For example, the strategy identified such initiatives as modifyingfederal grant requirements and consolidating funding sources to state andPage 6GAO-04-433 Homeland Security

local governments. The strategy further recognized the importance ofassessing the capability of state and local governments, developing plans,and establishing standards and performance measures to achieve nationalpreparedness goals.Recent reports by independent research organizations have highlightedthe same issues of the need for intergovernmental coordination, planning,and assessment. For example, the fifth annual report of the Advisory Panelto Assess Domestic Response Capabilities for Terrorism InvolvingWeapons of Mass Destruction2 (the Gilmore Commission) also emphasizesthe importance of a comprehensive, collaborative approach to improve thenation’s preparedness. The report states that there is a need for acoordinated system for the development, delivery, and administration ofprograms that engage a broad range of stakeholders. The GilmoreCommission notes that preparedness for combating terrorism requiresmeasurable demonstrated capacity by communities, states, and the privatesector to respond to threats with well-planned, well-coordinated, andeffective efforts by all participants. The Gilmore Commission recommendsa comprehensive process for establishing training and exercise standardsfor responders that includes state and local response organizations on anongoing basis. The National Academy of Public Administration’s recentpanel report3 also notes the importance of coordinated and integratedefforts at all levels of government and in the private sector to develop anational approach to homeland security. Regarding assessment, the reportrecommends establishing national standards in selected areas anddeveloping impact and outcome measures for those standards.The creation of DHS was an initial step toward reorganizing the federalgovernment to respond to some of the intergovernmental challengesidentified in the national strategy. 4 The reorganization consolidated22 agencies with responsibility for domestic preparedness functions to,among other things, enhance the ability of the nation’s police, fire, and2The Advisory Panel to Assess Domestic Response Capabilities for Terrorism InvolvingWeapons of Mass Destruction, The Fifth Annual Report to the President and the Congress,Forging America’s New Normalcy: Securing our Homeland, Protecting Our Liberty(Arlington, VA.: Dec. 15, 2003).3National Academy of Public Administration, Advancing the Management of HomelandSecurity: Managing Intergovernmental Relations for Homeland Security (Washington,D.C.: February 2004).4Homeland Security Act of 2002 (P. L. 107-296 (2002)).Page 7GAO-04-433 Homeland Security

other first responders to respond to terrorism and other emergenciesthrough grants. Many aspects of DHS’s success depend on its maintainingand enhancing working relationships within the intergovernmental systemas the department relies on state and local governments to accomplish itsmission. The Homeland Security Act contains provisions intended tofoster coordination among levels of government, such as the creation ofthe Office of State and Local Government Coordination and ONCRC.The Homeland Security Act established ONCRC within DHS to overseeand coordinate federal programs for, and relationships with, state, local,and regional authorities in the National Capital Region.5 Pursuant to theact, ONCRC’s responsibilities include coordinating the activities of DHS relating to NCR, including cooperatingwith the Office for State and Local Government Coordination; assessing and advocating for resources needed by state, local, and regionalauthorities in NCR to implement efforts to secure the homeland; providing state, local, and regional authorities in NCR with regularinformation, research, and technical support to assist the efforts of state,local, and regional authorities in NCR in securing the homeland; developing a process for receiving meaningful input from state, local, andregional authorities and the private sector in NCR to assist in thedevelopment of the federal government’s homeland security plans andactivities; coordinating with federal agencies in NCR on terrorism preparedness toensure adequate planning, information sharing, training, and execution ofthe federal role in domestic preparedness activities; coordinating with federal, state, and regional agencies and the privatesector in NCR on terrorism preparedness to ensure adequate planning,information sharing, training, and execution of domestic preparednessactivities among these agencies and entities; and serving as a liaison between the federal government and state, local, andregional authorities, and private sector entities in NCR to facilitate accessto federal grants and other programs.5P.L. 107-296 §882.Page 8GAO-04-433 Homeland Security

The act also requires ONCRC to submit an annual report to Congress thatincludes the identification of resources required to fully implement homelandsecurity efforts in NCR, an assessment of the progress made by NCR in implementing homelandsecurity efforts in NCR, and recommendations to Congress regarding the additional resources neededto fully implement homeland security efforts in NCR.The first ONCRC Director served from March to November 2003, and theSecretary of DHS appointed a new Director on April 30, 2004. The ONCRChas a small staff including full-time and contract employees and staff ondetail to the office.Page 9GAO-04-433 Homeland Security

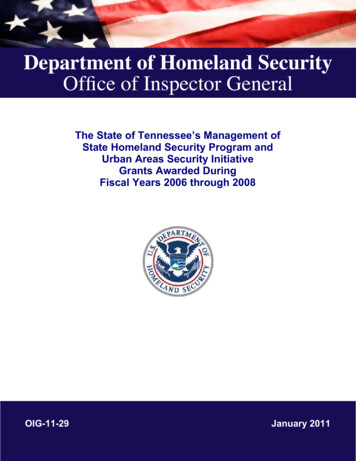

Figure 1: National Capital Region JurisdictionsMontgomery CountyDistrict ofColumbiaArlingtonCountyLoudoun CountyPrince George'sCountyCity of AlexandriaFairfax CountyPrince WilliamCountyVirginiaMarylandSource: National Capital Planning Commission.NCR is a complex multijurisdictional area comprising the District ofColumbia and surrounding counties and cities in the states of Marylandand Virginia and is home to the federal government, many nationallandmarks, and military installations. Coordination within this regionPage 10GAO-04-433 Homeland Security

presents the challenge of working with eight NCR jurisdictions that vary insize, political organization, and experience with managing emergencies.The largest municipality in the region is the District of Columbia, with apopulation of about 572,000. However, the region also includes largecounties, such as Montgomery County, Maryland, with a total populationof about 873,000, incorporating 19 municipalities, and Fairfax County,Virginia, the most populous jurisdiction (about 984,000), which iscomposed of nine districts. NCR also includes smaller jurisdictions, suchas Loudoun County and the City of Alexandria, each with a populationbelow 200,000. The region has significant experience with emergencies,including natural disasters such as hurricanes, tornadoes, and blizzards,and terrorist incidents such as the attacks of September 11, andsubsequent events, and the sniper incidents of the fall of 2002. For moredetails on the characteristics of the individual jurisdictions, see table 1.Page 11GAO-04-433 Homeland Security

Table 1: Characteristics of National Capital Region cteristicsPopulation(2000 Census)BudgetMarylandMontgomery CountyCounty has 19municipalities and anelected countyexecutive and countycouncil873,341 3.1 billion(FY 2004Adopted)Prince George’sCountyCounty has 27municipalities and anelected county counciland county executive801,515 1.8 billion(FY 2004Adopted)City council, cityadministrator, andmayor572,059 1.8 billion(FY 2004Adopted)Alexandria CityElected mayor and citycouncil and appointedcity manager128,283 479.2 million(FY 2004Adopted)Arlington CountyElected county boardand appointed countymanager189,453 805.3 million(FY 2004Adopted)Fairfax CountyCounty has 9 districts;an elected board ofsupervisors, and anappointed countyexecutive984,366 2.6 billion(FY 2004Adopted)Loudoun CountyCounty has 8 districtscontaining 7 towns, anelected board ofsupervisors, and anappointed county

Loudoun County Prince William County Fairfax County Montgomery County Prince George's County Source: National Capital Planning Commission. Arlington County District of Columbia Virginia Maryland City of Alexandria Since the tragic events of September 11, 2001, the National Capital Region (NCR), comprising jurisdictions including the District

![Table 1 [ IMG1]: Codes to Identify Neuroimaging in Administrative .](/img/42/chipra-0198-tables1-9.jpg)