Transcription

e76Journal for Healthcare QualityReducing Depressive Symptoms in NursingHome Residents: Evaluation of thePennsylvania Depression CollaborativeQuality Improvement ProgramScott D. Crespy, Kimberly Van Haitsma, Morton Kleban, Carolyn J. HannAbstract: Depression reduces quality of life for nursing home(NH) residents and places them at greater risk for disability,medical morbidity, and mortality. However, accumulatingevidence suggests that interventions for early detection andtreatment can mitigate symptoms of clinical and subclinicallevels of depression. The Promoting Positive Well-Being(PPW) program is a quality improvement (QI) interventionthat features tools and strategies to assist NHs in early identification, assessment, treatment, and monitoring of residentswith depressive symptoms. The PPW was evaluated in 40 NHsthrough an 8-month QI collaborative that provided participants with tools, webinar training, and technical support.Results showed a significant group by time interaction effectwith facility quality rating as a covariate; the active group (n 18 NHs) outperformed the waitlist control group (n 19 NHs). Inall, there was a 58% relative reduction in the percentage ofresidents with self-reported moderate-to-severe depressivesymptoms. Most NHs reported that they were satisfied with thecollaborative (97%) and would recommend it to others (86%);only 15% reported significant challenges. The rate of webinarattendance and data submission compliance was 92%. Resultssuggest that PPW is a promising approach that should befurther evaluated in larger NH initiatives and other settings.Keywordsquality improvementdepressionnursing home residentsJournal for Healthcare QualityVol. 38, No. 6, pp. e76–e88 2016 National Association forHealthcare QualityIntroductionDepression is a serious and persistentconcern in nursing homes (NHs). Estimates of depressive symptoms for the nation’s 1.5 million NH residents range from22% to 40% (American Geriatrics Societyand American Association for GeriatricPsychiatry, 2003; Sahyoun et al., 2001).Depression not only causes psychologicalsuffering and reduces quality of life butalso places residents at higher risk fordisability, medical morbidity, and mortality (Gerritsen et al., 2011; Meeks et al.,2015; Volicer et al., 2011).Nursing homes diagnose depressionmore frequently than ever before (Gabodaet al., 2012), but the quality of care and rangeof interventions and monitoring remainsuneven. In many NHs, antidepressantmedications are the first-line treatment(Thakur and Blazer, 2008). Although beneficial for some residents, psychopharmacotherapy carries the risk of side effects, andexperts have raised concerns about thequality of medication management (Meekset al., 2015). A growing body of evidencesuggests that psychosocial interventions,such as behavioral activation, psychotherapy,and social support, can alleviate depressivesymptoms. However, these approaches areused in NHs much less commonly thanmedications (American Geriatrics Societyand American Association for Geriatric Psychiatry, 2003; Bharucha et al., 2006; Blazerand Hybels, 2005; Cohen and Wills, 1985;Dimidjian et al., 2006; Geerlings et al., 2000;Meeks et al., 2015; Snowden et al., 2003;Taylor and Lynch, 2004).As new research findings emerge, NHsface the challenge of integrating into dailyoperations the latest evidence-based practices to reduce depressive symptoms. Toaddress this problem, a team of researchersand clinicians developed the PromotingPositive Well-Being (PPW) program, a quality improvement (QI) intervention thatfeatures tools and strategies designed toassist NH care teams in early identification,assessment, treatment, and monitoring ofresidents with depressive symptoms. ThePPW aims to provide NHs with an efficientsystem to track and improve the effectivenessof depression management for individualsand facility wide. It is designed for ease ofCopyright 2016 National Association for Healthcare Quality. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Vol. 38 No. 6 November/December 2016implementation in traditional NHs, withoutthe addition of staff or other resources.Developing the Promoting PositiveWell-Being ToolkitIn 2007, the research team created PPWand the associated implementation toolkit. The program is based on the theoretical model by Lewinsohn (1975), whichposits that depression results from aninteraction of individual vulnerabilities,environmental stressors, disruption ofpreferred behavioral patterns, and emotional responses. Promoting Positive WellBeing has four main components:1. Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) depression screening tool (Kroenkeet al., 2001). This validated instrumentidentifies depressive symptoms frommild to severe and is part of the federally mandated Minimum Data Set(MDS) 3.0, which all NHs are requiredto administer to residents at leastevery quarter (Centers for Medicareand Medicaid Services, 2014). Residents scoring 5 or greater are candidates for PPW.2. Clinical guidelines for evidence-basedtreatment: PPW provides for threelevels of intervention: (1) BehavioralActivation, which aims to increase theavailability and frequency of preferredactivities, restorative nursing, andexercise; (2) Enhanced Social Support, involving family as well as socialwork and chaplaincy services; and (3)Mental Health treatment, administered by psychologists or psychiatristsand including psychotherapy and/orantidepressant medications. Generally, psychosocial interventions arerecommended as the first-line treatment for residents with mild levels ofdepression. Psychological and psychiatric services are advised for residentswith more significant or sustainedsymptoms, suicidal ideation, or a history or preference for this form of care.3. Wellness Rounds: Interdisciplinarycare teams plan services based oneach resident’s individual needs,e77background, and preferences. Atprescribed intervals, teams revieweach person’s response to treatmentand refine the care plan as needed.An integral part of the program,Wellness Rounds use QI approaches,including the Plan-Do-Study-Act(PDSA) cycle and root cause analysis,to identify when interventions areworking and when they are not, aswell as to devise more effective treatment strategies for each resident.4. Case management tools and preprogrammed Excel spreadsheet totrack resident depression symptomseverity scores and levels of intervention. Residents are assessed uponadmission to the NH and every 3months thereafter (or sooner if thereis a significant change in status). Thefrequency of assessment follows Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (2014) procedures mandated forNHs. Care teams document in anExcel spreadsheet each resident’sdepression severity score and interventions received. The resultingreport allows staff to easily see trendsin each individual’s depression scores,measure progress toward symptomrelief, and problem solve duringWellness Rounds. Also, the spreadsheet automatically calculates population statistics (aggregate results)for all NH residents, month by monthand year to date. This information isvaluable for making improvements atthe system level.The PPW toolkit describes each component in depth and is available for freedownload (Abramson Center for JewishLife, 2011).In 2007, PPW was piloted for 10 monthswithin a 324-bed not-for-profit NH. Sixtyseven residents were enrolled in the program and received follow-up screening.Results were promising: two thirds of theparticipants experienced some improvement in their depressive symptoms and42% went from a positive screen (GeriatricDepression Scale—Short Form score 15;Cornell Scale for Depression in DementiaCopyright 2016 National Association for Healthcare Quality. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

e78Journal for Healthcare Qualityscore 12) on the initial depressionscreening to a negative screen (indicatingfewer depressive symptoms) at follow-up(Alexopoulos et al., 1988; Crespy, et al.,2008; Yesavage, 1988).In 2011, 40 Pennsylvania NHs took partin a proof-of-concept study for the PPWprogram. The goals was to evaluate whether(1) residents receiving the PPW programwould experience a reduction in depressivesystems as compared with others in a waitlistcontrol group and (2) diverse NHs wouldfind the program acceptable and feasible toimplement.Study Design and MethodsThe PPW project was conducted as a QIinitiative. A federally assured institutionalreview board reviewed the project andgranted a waiver of informed consent.Identification, Enrollment, andRandomization of Participating NHsThe project recruited participating NHswith the help of four Pennsylvania healthcare provider associations, which eithercontacted facilities directly or provideda mailing list to the project team. The first 40NHs that volunteered to participate becamethe convenience sample for the project.Administrators at the participating sitessigned a letter pledging that the facilitywould identify an onsite project coordinator,provide information about organizationalcharacteristics, take part in training sessionsand monthly conference calls, use PPW toolsduring the project, submit monthly aggregate QI tracking forms, and complete periodic surveys. In most NHs (60%), a socialworker served as the site coordinator.Nursing homes were randomly assigned to the active (n 20) or waitlistcontrol group (n 20). Based on data fromthe sites, the two groups were balancedboth by facility size (small: ,100 beds,large: 100 beds) and ownership type (forprofit, not-for-profit, county). Facilities inthe active group had a total of 2,256 duallycertified beds; those in the waitlist controlgroup had a total of 3,169 beds.Nursing homes in the active group beganoffering the PPW program immediatelyafter receiving training. Waitlist control NHsoffered usual care for the first 4 months ofthe study; at the end of this period, theyreceived PPW training and beganimplementation.Procedures for Nursing Homes ImplementingPromoting Positive Well-BeingTraining. The research team providedfour live 1-hour training webinars coveringdepression in older adults, PHQ-9 screening,and recommended clinical interventions,including therapeutic recreation, restorativenursing, exercise, social work, chaplaincy,and psychological and psychiatric services.Also, the training addressed special needs ofsuicidal residents as well as Wellness Rounds,the QI process, and data collection requirements. Webinars were audio recorded andavailable for staff who could not attendlive sessions. The PPW training resourcesare available online (Abramson Centerfor Jewish Life, 2011).Depression Screening. Nursing homeresidents capable of being interviewed werescreened, usually by a social worker, at regular intervals outlined by MDS 3.0 requirements (i.e., typically upon facility admissionand at least 3-month intervals). The PHQ-9scores range from 0 to 27. Scores of 5–9 wereconsidered to reflect mild depression; 10–14reflected moderate depression; 15–19,moderately severe depression; and 20–27,severe depression. Nursing home residentsscoring 5 or greater were enrolled in thePPW program. When residents were notcapable of answering questions on theirown, NHs followed MDS 3.0 procedures tointerview staff regarding residents’ depressive symptoms. Facilities were encouraged toexclude short-stay residents from the QIstudy because the PPW program was developed with long-stay residents in mind.However, the extent to which NHs excludedshort-stay residents is unknown.Care Planning. Interdisciplinary careteams met for Wellness Rounds to revieweach enrolled resident’s needs, preferences, and history. Teams created anindividualized treatment plan that drew onCopyright 2016 National Association for Healthcare Quality. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Vol. 38 No. 6 November/December 2016PPW guidelines for (1) Behavioral Activation, (2) Enhanced Social Support, and (3)Mental Health Treatment (for details, seeAbramson Center for Jewish Life, 2011).Follow-up Screening and WellnessRounds. Every 6 weeks, the social workerbrought current PHQ-9 screening toolscores, along with clinical observations, toWellness Rounds. During these sessions,the team reviewed the resident’s responseto treatment and modified the care plan asneeded.Discharge From Promoting PositiveWell-Being. Residents stayed in the PPWprogram as long as depressive symptoms(PHQ-9 score of 5 or above) remained.Those discharged from the programreceived quarterly depression screeningsas part of the MDS 3.0.Telephone Support. Throughout theproject, facilities in the active group wereencouraged to contact the principalinvestigator with questions and attendmonthly conference calls (typically lasting45 minutes) to problem solve and sharebest practices with staff from other NHs inthe active group.Recording Resident Data and CalculatingAggregate Depression Indicators. Facilities were asked to use the PPW Excelspreadsheet and case management toolsto record PHQ-9 scores for all NH residents on a monthly basis. The spreadsheetautomatically calculated a percentage ofpositive depression screens based on theratio of positive PHQ-9 depression screensin the numerator to the total number ofMDS assessments completed per month asthe g Feasibility. At Month 6, sitecoordinators completed a questionnaire(40 items) regarding staff experiences withPPW. The evaluation form asked about thewebinar training experience, trainingmanual, monthly collaborative conferencecalls, Wellness Rounds, case managementand spreadsheet tool, implementatione79challenges, and overall satisfaction withthe PPW program and collaborative. Responses for most questions used a 5-pointLikert scale with a range from “CompletelyAgree” to “Completely Disagree.” Also, thequestionnaire asked about leadershipturnover (NH administrator and directorsof nursing, medicine, social work, and recreation therapy) and staffing levels.Procedures for Waitlist Control NursingHomesDuring the first 4 months of the project,each NH in the waitlist control groupscreened residents using the PHQ-9 andprovided usual care. The facilities followedtheir own organizational policies and procedures, as well as governmental recommendations regarding triggers for careplanning development, implementation,and evaluation. Recommended triggers aresymptoms of anhedonia, suicidal ideation,and an elevated total PHQ-9 severity score( 10) (Centers for Medicare and MedicaidServices, 2014). These recommendationsapplied equally to participants in the activeand usual care groups. The waitlist controlNHs followed the same procedures as activesites to record individual resident data,calculate aggregate depression indicators,and fax results to the research team.After 4 months, waitlist control facilitiestook part in the same webinar training,monthly teleconference calls, and implementation procedures as the activegroup. During Month 6 of the collaborative, site coordinators completed theevaluation questionnaire asking abouttheir experience with PPW. At this point,waitlist control facilities had implementedPPW for 2 months, whereas the activegroup had offered the program for 6months.Primary Outcome MeasureNursing homes delivering the intervention faxed the aggregate level depressionindicator results to the research team ona monthly basis. The data included number of MDS assessments completed permonth, number of positive depressionCopyright 2016 National Association for Healthcare Quality. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

e80Journal for Healthcare Qualityscreens (i.e., PHQ-9 of 10, MDS SectionD: Mood), and number of residents whoreceived care planned interventions bylevel type (i.e., Level 1: Behavioral Activation, Level 2: Enhanced Social Support/Adjustment, Level 3: Mental Health Treatment). Individual resident-level information was not shared with researchers.Nursing home staff satisfaction with PPWwas assessed at 6 months from the projectstart by way of a mailed staff evaluationform.Study Design and Analytic StrategyThe study hypothesis was that facilities inthe active group would experiencea decrease in the percentage of residentswith depressive symptoms compared withwaitlist control facilities.During the 4-month randomized controlled portion of the QI initiative, thedesign used a two-group by four timeperiod repeated-measures analysis ofvariance (ANOVA). Facilities were nested within one of the two groups: theactive group offered the PPW intervention and the waitlist control providedusual care for the first 4 months of thestudy. The comparison between the twogroups has a separate error term withfacilities nested within groups. The“within” effects of time and group · timeinteractions uses the residual error termfor its F ratios.Statistical AnalysesAn ANOVA was used to analyze the data,contrasting Group 1 versus Group 2 during the first four time months. There wasa minimal amount of missing data, substantially less than 10% at each timeperiod. Missing data were imputed usingStata’s regression procedure. Effect size(ES) information was generated for all ofthe ANOVA main effects. The calculationswere accomplished by estimating the h2 foreach F ratio from the sum of squares in thesource table output. The h2 SS (effect)/(SS [effect] 1 SS [error term]). TheANOVA ES, f, were then estimated ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffithe h2 ð12h2 Þ.ResultsNursing Home CharacteristicsParticipating NHs had an average of 135.6beds (compared with the national average,107.6). Nursing homes were randomly assigned to the active or waitlist control group;groups were balanced based on type ofownership (for-profit, not-for-profit, orcounty) and by size (small: ,100 beds orlarge: 100 beds). There were no significantdifferences between the two groups in fourkey areas: (1) reported turnover amongfacility leaders (i.e., long-term care administrator and directors of nursing, medicine,social work, and recreation); (2) staff-toresident ratios (for social services and recreation personnel as well as certified nursingassistants on the day or afternoon shift); (3)hours per week the medical director, psychiatrist or psychiatric nurse, and psychologist were physically present in the facility;and (4) facility 5-star Centers for Medicareand Medicaid Services (CMS) quality ratings(mean 3.45 waitlist controls, mean 3.55active group) (Tables 1 and 2).Completion RatesAltogether, 37 NHs participated and submitted data throughout the 8-monthcollaborative (92% completion rate).Twenty-nine completed the evaluationsurvey (72.5%). Three NHs did not complete the project (two from the active andone from the waitlist control group). Reasons for not completing the project werethat two facilities lost key staff members anda third reported having too many organizational changes to continue participation.Participation in Training WebinarsThe majority of facilities attended the fourlive 1-hour webinars (percentage of sitesper session: 85–100%).Comparison of Percentage of ResidentsExperiencing Moderate-to-Severe Depressionin Active and Waitlist Control GroupAt Month 4, the analysis examined results for residents scoring 10 or greaterCopyright 2016 National Association for Healthcare Quality. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

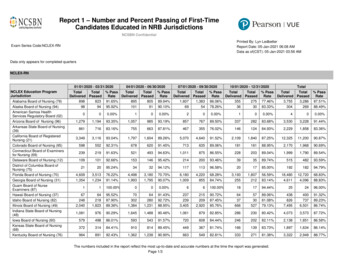

Vol. 38 No. 6 November/December 2016e81Table 1. Pennsylvania Depression Collaborative: Characteristics ofNursing Home Sample: Facilities by Number of CertifiedBeds and Ownership Type (N 40)Ownership TypeSmall ,100 Beds;Large 100 BedsSmallGroupActive Group*Control Group†TotalLargeGroupActive GroupControl GroupTotalTotalGroupActive GroupControl GroupTotalCountyFor ProfitNot for 141125202040Source: html. The activeand waitlist control groups were balanced by size (small or large) and ownershipstatus (county, for profit, or nonprofit).*Nursing homes in the active group had a total of 2,256 certified beds.†Nursing homes in the waitlist control group had a total of 3,169 certified beds.on the PHQ-9 MDS 3.0 screening tool.Individuals scoring in this range areimportant as a group because (1) a scoreof 10 is the traditional indicator forbeing “at risk” for moderate-to-severedepression on the PHQ-9, (2) this leveltriggers an MDS-related Care AreaAssessment process, or more thoroughexploration, for the resident, and (3)scores at this level appear on a facility’sCMS quality indicator, “Percentage oflong-stay residents who have depressivesymptoms.”Altogether, 22,682 depression screenings occurred across groups during the8-month study period. Figure 1 shows theTable 2. Pennsylvania Depression Collaborative: Characteristics ofNursing Home Sample: Facilities by Medicare QualityMeasure Rating (N 40)Medicare 5-StarQuality Rating1 Star2 Stars3 Stars4 Stars5 StarsTotal NHsActiveWaitlist controlTotal11222478155510549202040Source: html.NH, nursing home.Copyright 2016 National Association for Healthcare Quality. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

e82Journal for Healthcare QualityFigure 1. Depressive symptoms in 37 facilities over 4 months foractive (black bars) versus waitlist control group facilities(gray bars).Percentage of Moderate to Severe Depressive Symptoms(Active Group n 18; Control Group n 6.2%Active GroupControl GroupMonthJun-11May-11Apr-11Mar-110%For subjects with PHQ-9 scores of 10 or more, there were no significant findings forthe contrasts among groups (F1,37 0.01, p .92, f 0.02 [low ES]) or over time (F3,111 1.99, p .12, f 0.23 [medium ES]). However, the group · time interaction wassignificant (F3,111 3.73, p .01, f 0.32 [high medium ES]). Percentage of moderate-tosevere depressive symptoms: months 1 through 4 (active group n 18; control groupn 19) and moderate-to-severe depression (PHQ-9 10). ES, effect size; PHQ-9, PatientHealth Questionnaire.percentage of subjects with moderate-tosevere levels of depressive symptoms.For subjects with PHQ-9 scores of 10 ormore, there were no significant findings forthe contrasts among groups (F1,37 0.01,p .92, f 0.02 [low ES]) or over time (F3,111 1.99, p .12, f 0.23 [medium ES]). However,the group · time interaction was significant(F3,111 3.73, p .01, f 0.32 [high mediumES]). The comparison of the cell means forthe simple significant interaction effects werethe following: (1) F1,111 10.78, p .001 for(Group 1 · Time 1 2 Group 1 · Time 3) 2(Group 2 · Time 1 2 Group 2 · Time 3)and (2) F1,111 4.85, p .03 for (Group 1 ·Time 1 2 Group 1 · Time 4) 2 (Group 2 ·Time 1 2 Group 2 · Time 4). In both simpleinteractions, one can observe drops in cellmeans in Group 1, and within Group 2,a simultaneous and related increase in cellmeans indicating that the facilities in theactive group reported significantly lowerpercentages of residents with significantdepressive symptoms over time, whereaswaitlist control facilities reported significantlyhigher percentages of residents with significant depressive symptoms over time.Follow-up Comparison of Percent ofResidents Experiencing Moderate-to-SevereDepressionResidents scoring 10 or greater on thePHQ-9 MDS screening tool in the activegroup were followed for an additional 4months (8 months in total).Eight months after training, NHs in theactive group continued to demonstratea decline in the percentage of residentswith depressive symptoms (Figure 2). In all,there was a 58% relative reduction in thepercentage of residents with moderate-tosevere depressive symptoms (10.1% in March2011; 4.2% in October 2011). Althoughacross the 8 months the ANOVA was notstatistically significant, the results remainedintriguing given the low-to-moderate ES; thissuggests the need for more facilities to adequately test the intervention’s impact over an8-month period.Copyright 2016 National Association for Healthcare Quality. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

Vol. 38 No. 6 November/December 2016Staff Evaluation Form ResponsesAfter the first 6 months of the project,coordinators at the 37 fully participatingNHs were asked to provide feedback onPPW (Table 3). At this point, sites in theactive group had 6 months of experiencewith the intervention, whereas waitlistcontrol group facilities had only 2 monthsof experience with the intervention.Approximately three fourths (active 80%,waitlist control 65%) of participating NHssubmitted the 6-month evaluation survey.Despite the uneven evaluation timeframe, there were no differences betweenmean ratings by active and waitlist facilitieson the evaluation measures. Most site coordinators (97%) were satisfied with thematerials, training, and support theyreceived from the collaborative and wouldrecommend it (86%) to other NHs. Sitecoordinators found the webinars comprehensive and of high quality (90%), thetoolkit comprehensive (94%), and thedatabase easy to use (89%). Three fourthssaid that the program helped them providebetter services to residents at risk fordepression. Most reported that the NHconducted Wellness Rounds (82%), withregular participation from social work,nursing, and recreation staff (93% respectively). In some cases, staff from chaplaincy(26%) as well as medicine, psychology,psychiatry, and quality (11% respectively)also attended regularly. Overall, 70% ofNHs incorporated discussion of PHQ-9scores and symptoms in interdisciplinarymeetings. A majority of NHs found it easy toincorporate the depression and management program (63%), and only 15%reported significant implementationchallenges. The most frequent issues werelack of staff or staff time, staff resistance tochanging routines, and staff turnover.DiscussionImplementation of PPW training sessions,tools, and QI strategies resulted in a significant reduction in depressive symptomswhen comparing NHs in the active groupversus waitlist controls. A 58% relativereduction was seen in the percentage ofresidents in the active group with depressivee83Figure 2. Depressive symptoms in 18 active and 19waitlist control group facilities over an8-month period.A 58% reduction in depressive symptoms was found in theactive group from the first to last month measurement. Note: InJuly 2011, waitlist control facilities received training and beganimplementing the PPW intervention. Training for the controlgroup occurred over a 4-week period in July 2011. Data forAugust, September, and October were the only data afterintervention. Little to no quarterly depression reassessmentdata are included in the truncated measurement phase for thecontrol group. Percentage of moderate-to-severe depressivesymptoms: Months 1 through 8 (active group n 18; controlgroup n 19) and moderate-to-severe depression (PHQ-9 10).PHQ-9, Patient Health Questionnaire.symptoms. The QI initiative results wereencouraging, even in light of caveats aboutthe depressive symptom data (notably, thelow rates of depressive symptom detectionusing the PHQ-9). Generally, sites werehighly satisfied with the program and foundit feasible to implement. Challenges citedby staff were not remarkable for this setting.Findings from the project suggest thatthe NH community may benefit fromguidance which includes (1) effective useof a depression screening tool and a prevention focus, (2) evidenced-based discipline-specific practices offering a stepwiseapproach that uses behavioral interventions first for uncomplicated residentswith mild levels of depression, and (3) QImethods, used in the context of aninterdisciplinary team, to address bothCopyright 2016 National Association for Healthcare Quality. Unauthorized reproduction of this article is prohibited.

e84Journal for Healthcare Qualityindividual clinical and aggregate systemdomains.Horwath and colleagues (1992) suggested that an individual with subsyndromal levels of depressive symptoms ismore than four times more likely todevelop new-onset major depressive disorder than an individual without depressive symptoms. The authors go on torecommend the use of early screening fordepressive symptoms and the delivery ofeffective preventive intervention programs. The current PPW study trainedNHs to identify residents whose depressivesymptoms fell in the mild range (5–9) andin the moderate-to-severe range ( 10).Nursing homes were encouraged toadminister behavioral approaches to residents experiencing mild levels of depression with the goal of avoiding symptomintensification.With access to facility aggregate data only,it is beyond the scope of the PPW study toknow whether the prevention focus (i.e.,addressing mild level of symptoms) contributed significantly to an overall reduction inthe percentage of residents with moderateto-severe levels of depression. However,future studies using resident-specific datamay examine whether the prevention focushelped stave off deepening depression.The results suggest that NHs may benefit from incorporating QI elements, suchas regular interdisciplinary rounds andsystems to assess individual gains andidentify effective interventions, when implementing a depression prevention andmanagement program. The PDSA cycle isa valuable tool to track and trend resultsand make individual and system-level improvements. The continuous monitoringof aggregate data provides NHs withinformation to make changes when variation occurs. Future studies may betterisolate and measure the effectiveness ofthese QI strategies.Study Limitations and Directions for FutureResearchThe reduction in the percentage of residents with depressive symptoms was achieved despite the low ES of the PPWintervention. According to the 6-monthevaluation findings, several challengesmay have contributed to the overall smallES: (1) staff turnover and competing priorities at NHs, (2) lack of specificityregarding intervention intensity/dosage,(3) brief time period for intervention implementation, (4) unknown sustainabilityove

severe depression. Nursing home residents scoring 5 or greater were enrolled in the PPW program. When residents were not capable of answering questions on their own, NHs followed MDS 3.0 procedures to interview staff regarding residents' depres-sivesymptoms.Facilitieswereencouragedto exclude short-stay residents from the QI