Transcription

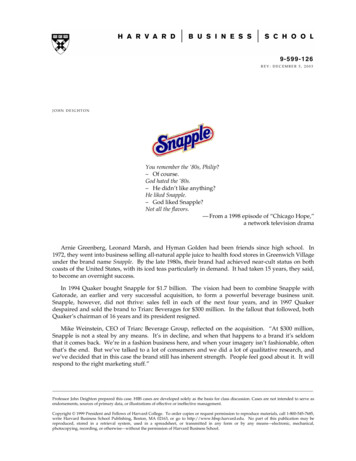

9-599-126REV: DECEMBER 5, 2003JOHN DEIGHTONYou remember the ‘80s, Philip?– Of course.God hated the ‘80s.– He didn’t like anything?He liked Snapple.– God liked Snapple?Not all the flavors.—!From a 1998 episode of “Chicago Hope,”a network television dramaArnie Greenberg, Leonard Marsh, and Hyman Golden had been friends since high school. In1972, they went into business selling all-natural apple juice to health food stores in Greenwich Villageunder the brand name Snapple. By the late 1980s, their brand had achieved near-cult status on bothcoasts of the United States, with its iced teas particularly in demand. It had taken 15 years, they said,to become an overnight success.In 1994 Quaker bought Snapple for 1.7 billion. The vision had been to combine Snapple withGatorade, an earlier and very successful acquisition, to form a powerful beverage business unit.Snapple, however, did not thrive: sales fell in each of the next four years, and in 1997 Quakerdespaired and sold the brand to Triarc Beverages for 300 million. In the fallout that followed, bothQuaker’s chairman of 16 years and its president resigned.Mike Weinstein, CEO of Triarc Beverage Group, reflected on the acquisition. “At 300 million,Snapple is not a steal by any means. It’s in decline, and when that happens to a brand it’s seldomthat it comes back. We’re in a fashion business here, and when your imagery isn’t fashionable, oftenthat’s the end. But we’ve talked to a lot of consumers and we did a lot of qualitative research, andwe’ve decided that in this case the brand still has inherent strength. People feel good about it. It willrespond to the right marketing stuff.”Professor John Deighton prepared this case. HBS cases are developed solely as the basis for class discussion. Cases are not intended to serve asendorsements, sources of primary data, or illustrations of effective or ineffective management.Copyright 1999 President and Fellows of Harvard College. To order copies or request permission to reproduce materials, call 1-800-545-7685,write Harvard Business School Publishing, Boston, MA 02163, or go to http://www.hbsp.harvard.edu. No part of this publication may bereproduced, stored in a retrieval system, used in a spreadsheet, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical,photocopying, recording, or otherwise—without the permission of Harvard Business School.

599-126Snapple1972–1986: The Origins of the BrandArnie Greenberg’s family ran a sardine and pickle store in Ridgewood in Queens, New York. Hisfriends Leonard Marsh and Hyman Golden helped him in the store, and in turn he helped them tomanage their window-washing business. In the climate of the 1960s, Arnie encouraged the family tostock health foods. The three saw the popularity of natural no-preservative fruit juices in the store,and teamed up with a California-based juice company to manufacture and distribute a bottled appledrink. Eventually they broke away from the California partner and founded their own company—Unadulterated Food Products—and the Snapple brand.1 “100% Natural” became Snapple’s mantra.The business grew slowly using internally generated funds. It outsourced production andproduct development and built a network of distributors across New York City. Where possible, itsought individual distributors working for their own account, and found as a resultthat the business needed to broaden the product line to keep distributors occupied. Itadded carbonated drinks, fruit-flavored iced teas, diet juices, seltzers, an isotonicsports drink, and even a Vitamin Supreme. Some succeeded and many failed, butpremium pricing on the successful products covered losses on the failures. Revenuesand profits grew with expansion of distribution into New Jersey and Pennsylvania.In 1984 annual turnover was 4 million and it doubled by 1986 to 8 million.In response to pleas from Snapple’s distributors, the founders commissioned advertising.Jonathan Bond and Richard Kirshenbaum, who managed the Snapple account later, described thisearly advertising as follows:When tennis star Ivan Lendl was featured in several ads, the idea didn’t quite come off.(He) kept mispronouncing the name as “Shnapple.” Luckily the ads were so bad that theydidn’t do the brand any harm. Had those schlocky ads been just a little better, they actuallywould have been worse for Snapple. The ineptness of the ads actually came off as charming,just like the cluttered packaging.2Snapple was just one of many small beverage brands aspiring to appeal to young, healthconscious urban professionals in the 1980s. Napa Naturals, Natural Quencher, SoHo, After the Fall,Ginseng Rush, Elliot’s Amazing, Old Tyme Soft Drink, Manly Sodas, Syfo, and Original New YorkSeltzer were some of the many contenders in what eventually came to be called the New Age orAlternative beverage category.1987–1993: The Glory YearsThe vision of many entrepreneurial founders was to exit via acquisition. For example, thefounders of SoHo—Connie Best and Sophia Collier—took sales to 25 million and then sold thecompany to liquor giant Seagram in 1989 for 15 million. They explained that they were handing offto a buyer with deeper pockets. Seagram expanded distribution and advertising, dismantling theindependent distribution network in favor of its own wine cooler distribution chain.The Snapple founders, however, decided to cope with the next stage of growth by hiringprofessional management. They turned to Carl Gilman, a beverage industry veteran from Seven-Up,1 Drawn from Cynthia Riggs, “Snapple Cracks Tough Pop Market,” Crain’s New York Business, August 14, 1989 and CaraTrager, “Niche Entrepreneurs,” Beverage World, October 1989.2 Jonathan Bond and Richard Kirshenbaum, Under the Radar (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1998).2

Snapple599-126to run sales and marketing. Gilman used focus groups to tell him how to improve Snapple’s labeldesign. He increased the advertising budget to 1 million and intensified the independent distributorsystem throughout the East Coast. He viewed expansion to the West Coast as premature and adilution of effort. “The stronger we build the East Coast, the more the West Coast will want us.”3The distribution system grew until Snapple had a network of 300 small, predominantly familyowned distributors servicing convenience chains, pizza stores, food service vendors, gasolinestations, and so-called mom-and-pop stores. A press story described the work as “salesman, truckloader, driver, heavy lifter and bill collector, all in one.”4 Distribution in Boston was in the hands ofTed Landers, who had married into a Boston beer distribution company and now employed 11people and several trucks to serve what he called the up-and-down-the-street business in soft drinks:In 1985 we were distributing several brands of single-serve beverage, SoHo and others. Wesaw lots of excitement around Snapple, and Snapple was doing its own distribution inBoston—about 250,000 cases a year—so we went to them and offered to grow their volume,which we did, up to a million cases a year. We invested in coolers and vending machines forconvenience stores, and talked up the product. We visited supermarkets, but they wantedslotting allowances and service calls, which can put a strain on my pocket book, so we stayedaway from them in the main. Supermarkets were no more than 10% of my volume in 1994.Nationally, supermarkets accounted for about 20% of Snapple’s sales.Snapple’s promotion was an offbeat blend of public relations and advertising. The story of thethree founders’ success in an industry dominated by multinational behemoths was told many timesin many media. Advertising agency Kirshenbaum, Bond & Partners created a spokesmodel for thebrand in the form of Wendy Kaufman, a former truck dispatcher with abrash New York attitude. Wendy received paid exposure in the brand’sadvertising, but her eccentric personality also attracted unpaid mediaattention. She appeared on television shows such as Oprah and DavidLetterman, where she read Letterman’s “Top 10 Least Favorite SnappleDrinks,” and was interviewed by USA TODAY. At times she attracted2,000 letters a week. She made appearances at retail stores, and acceptedinvitations to sleepovers, Bar Mitzvahs, and prom dates.In a similar vein, the brand sponsored the radio programs of two verypopular 1980s exponents of shock radio. Howard Stern specialized intasteless and often outrageously sexist humor, and Rush Limbaugh built afollowing as an advocate of right wing political and social ideas deliveredin a style that combined protracted ranting with acid sarcasm. Inexchange for sponsorships on both shows, the brand received on-airendorsement and sometimes became the subject of Stern’s banter and Limbaugh’s rants. Stern got toknow the founders of the business personally and conveyed to his listeners a genuine and infectiousregard for the products and the people behind them.Kirshenbaum, Bond adopted “100% Natural” not only as an advertising line, but as the test whichall marketing actions had to pass:3 Trager, op cit.4 Glen Collins, “On the Front Lines of the Beverage Wars: The Life of a Snapple Distributor, Surviving Robbers, Illegal Parkersand the Usual Cutthroat Competition,” The New York Times, December 3, 1997.3

599-126SnappleEverything should and would be natural and real. We would use real people in realcircumstances. Everything that happened on a Snapple shoot was real. And we would run onair only what really happened, even if it didn’t turn out the way we scripted it. We got a letterfrom a woman who claimed that her dog Shane came running every time he heard a Snapplecap being opened. We called him “Shane, the wonder dog.” But when we got there and triedit, nothing happened. The dog just sat there. So we ran the spot with the dog just lying there.5On a summer day in Hempstead, Long Island, Snapple invited consumers to a SnappleConvention. Over 5,000 people sent the required 5 and 20 Snapple labels, and participated in a dayof Snapple-themed fun and games. A Snapple fashion show was won by a woman in a dress made ofSnapple caps.Growth in the Alternative beverage category was explosive, with Snapple leading the way.Snapple sales grew from 80 million in 1989 to 231 million in 1992 and 516 million in 1993.Competition grew commensurately, though Snapple’s share remained steady at about 30%–40% ofthe rather hard-to-define category. (See Exhibits 1, 2, 3, 4, and 5 for estimates of the growth andstructure of the market and brand.) Brands like Clearly Canadian and Mistic appeared and Coke andPepsi were rumored to be entering. Seagram, however, failed to benefit from the market’s expansion,and sold SoHo for an estimated 1 million in 1992. Efforts to replicate its wine cooler success in theAlternative category had been unsuccessful. Industry observers attributed its difficulties to raisingprice, to tampering with flavors, and to dropping the patchwork of small distributors in favor of largeliquor wholesalers. Seagram’s president explained, “We are a large company and we should beoperating large businesses.”6In 1992, the three Snapple founders sold control of the company to a Boston private investmentbank—the Thomas H. Lee Company—in a leveraged buyout and subsequent public offering. In 1994with sales running at 674 million, Lee sold it to Quaker Oats for 1.7 billion in cash.1994–1997: Quaker Takes CommandQuaker in 1994 was a food company with four main areas of business: grain-based foods, beanbased foods, pet foods, and beverages. The first three were relatively mature, while the beveragebusiness, consisting entirely of the Gatorade brand, had been growing vigorously. Gatoradecontributed 1.1 billion of the company’s 5.95 billion turnover in that year.Gatorade’s origins were in a research project at the University of Florida in the early1960s to find a way to replenish fluids lost during exercise. The product, an uncarbonatedorange-flavored mix of water, salts and sugars, was tested on the school’s football team, theGators. It came to the notice of the sports world when the Gators beat Georgia Tech in the1969 Orange Bowl and Bobby Dodd, the losing coach, explained to Sports Illustrated: “Wedidn’t have Gatorade. That made the difference.” A small packaged goods marketing firm,Stokely-Van Camp, acquired the brand, took sales to nearly 100 million, and sold it toQuaker in 1983. Quaker took its sales to 1 billion in a decade.5 Bond and Kirshenbaum, op. cit.6 Eben Shapiro, “A Soda Seagram Didn’t Swallow,” The New York Times, March 21, 1992, p. 37.4

Snapple599-126Within the company, management attributed this growth to three main factors.7 First, Quakerexpanded the line. When Quaker bought the business, Gatorade was sold in 32-ounce bottles.Quaker added a 16-ounce glass bottle for the convenience store trade and 64-ounce and gallon plasticbottles for sale in supermarkets, and expanded from three to eight flavors. Second, Quaker increasedpromotional support. The brand became more visible in the major sports leagues, with MichaelJordan of the Chicago Bulls basketball team as a spokesman, and touchline visibility in the NationalFootball League’s televised games. Third, Quaker improved Gatorade’s distribution significantly.Internationally, it entered 26 foreign markets. Domestically, it improved coverage of the market andlowered its cost-to-serve by using the same logistics system that distributed Quaker’s breakfastcereals and snacks. It shipped Gatorade in full truckloads from Quaker-owned manufacturing plantsto the warehouses of the larger supermarket chains and the wholesalers who serviced smaller retailchains and independent supermarkets. From these warehouses Gatorade was combined with othergrocery products to make up full truckload deliveries direct to retail stores.Despite its success, some speculated that Gatorade could be an even larger brand in the hands of acompany with more scale in beverages. Indeed there was speculation that

12.11.2013 · saw lots of excitement around Snapple, and Snapple was doing its own distribution in Boston—about 250,000 cases a year—so we went to them and offered to grow their