Transcription

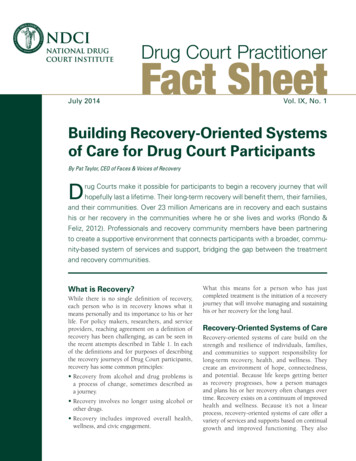

Drug Court PractitionerJuly 2014Fact SheetVol. IX, No. 1Building Recovery-Oriented Systemsof Care for Drug Court ParticipantsBy Pat Taylor, CEO of Faces & Voices of RecoveryDrug Courts make it possible for participants to begin a recovery journey that willhopefully last a lifetime. Their long-term recovery will benefit them, their families,and their communities. Over 23 million Americans are in recovery and each sustainshis or her recovery in the communities where he or she lives and works (Rondo &Feliz, 2012). Professionals and recovery community members have been partneringto create a supportive environment that connects participants with a broader, community-based system of services and support, bridging the gap between the treatmentand recovery communities.What is Recovery?While there is no single definition of recovery,each person who is in recovery knows what itmeans personally and its importance to his or herlife. For policy makers, researchers, and serviceproviders, reaching agreement on a definition ofrecovery has been challenging, as can be seen inthe recent attempts described in Table 1. In eachof the definitions and for purposes of describingthe recovery journeys of Drug Court participants,recovery has some common principles: Recovery from alcohol and drug problems isa process of change, sometimes described asa journey. Recovery involves no longer using alcohol orother drugs. R ecovery includes improved overall health,wellness, and civic engagement.What this means for a person who has justcompleted treatment is the initiation of a recoveryjourney that will involve managing and sustaininghis or her recovery for the long haul.Recovery-Oriented Systems of CareRecovery-oriented systems of care build on thestrength and resilience of individuals, families,and communities to support responsibility forlong-term recovery, health, and wellness. Theycreate an environment of hope, connectedness,and potential. Because life keeps getting betteras recovery progresses, how a person managesand plans his or her recovery often changes overtime. Recovery exists on a continuum of improvedhealth and wellness. Because it’s not a linearprocess, recovery-oriented systems of care offer avariety of services and supports based on continualgrowth and improved functioning. They also

TABLE 1 Definitions of RecoverySourceYearDefinitionCenter for SubstanceAbuse Treatment(CSAT)2005Recovery from alcohol and drug problems is a process ofchange through which an individual achieves abstinenceand improved health, wellness, and quality of lifeAmerican Society ofAddiction Medicine2005A patient is in a “state of recovery” when he or she hasreached a state of physical and psychological health suchthat his or her abstinence from dependency-producing drugsis complete and comfortableBetty Ford InstituteConsensus Panel2006A voluntarily maintained lifestyle characterized by sobriety,personal health, and citizenshipUK Drug PolicyCommission2008The process of recovery from problematic substance use ischaracterized by voluntarily sustained control over substanceuse which maximizes health and wellbeing and participationin the rights, roles, and responsibilities of societyScottish Government2008A process through which individuals are enabled to moveon from their problem drug use towards a drug-free life asan active and contributing member of society.SAMHSA2011Recovery from mental disorders and substance use disordersis a process of change through which individuals improve theirhealth and wellness, live a self-directed life, and striveto reach their full potentialSOURCE: Recovery Research Institute, 2012help build recovery-supportive communities thatprovide emphasis on the physical, social, spiritual,and cultural environments where people live theirdaily lives.Public policy considerations can impedeor promote the shift from a crisis-oriented,professionally directed, acute-care approachemphasizing treatment to one that is persondirected and recognizes the many pathways tohealth and wellness. With a greater focus on whathappens before and after treatment, public policiesthat affect a person’s ability to get and keep his orher life on track gain more importance. Becausediscriminatory public policies continue in the areas2 NDCI: The Professional Services Branch of NADCPof health care, employment, education, housing,and enfranchisement of those with past criminaljustice involvement, everyone who activelysupports the recovery process needs to work to enddiscriminatory policies.Changing how we think about and engage peoplewith addiction is an important part of buildingrecovery-oriented systems of care. Similar toother chronic health conditions, people withaddiction should be treated with dignity andrespect. Language and the words that we use totalk about people in or seeking recovery matterbecause it is such a stigmatized health condition.For example, terms such as substance abuse suggest

Building Recovery-Oriented Systemsof Care for Drug Court Participantsthat the individual is voluntarily misusing a substance. Ina randomized study of mental health professionals, whena person was described as a substance abuser as opposed tohaving a substance use disorder, clinicians perceived them asbeing responsible for their condition and were more likelyto agree that the person should be punished rather thantreated (Kelly et al., 2010). Further, recovery-oriented andstrength-based approaches avoid pathologizing a person’sexperience or defining them by their condition or disorder.Each Drug Court participant has strengths in addition to theissues that brought him or her to Drug Court. One way ofdetermining a person’s strengths is by conducting a recoverycapital assessment. This is a way to assess the person’sinternal and external strengths, supports, and resources,and to pinpoint areas that need attention, cultivation, orbolstering. Drug Court teams are uniquely positionedto change attitudes about people seeking recovery fromaddiction within the criminal justice system. They canengage participants with strength-based approaches,focusing on establishing trust, building relationships,reinforcing existing capabilities, and creating and locatingnew capabilities. When Drug Court teams elevate recoveryas the expectation, their relationships with participants andwith other service providers become transformed.Making Connections in RecoveryOriented SystemsOne of the essential ingredients for sustained recovery isconnection to family and community. Some Drug Courtshave successfully developed linkages with the broaderrecovery community during the Drug Court experience,setting the stage for postgraduate participation in formalservices and community supports. These activities, manyof which encourage the participation of families, can helpsupport long-term recovery following the Drug Courtexperience.A notable example is the Chittenden County Drug Courtin Vermont referring many participants to the TurningPoint Center of Chittenden County, a peer-run recoverycommunity center (Vermont Recovery Network, 2013).The court requires all new Drug Court participants toparticipate in a six-session peer-facilitated group calledMaking Recovery Easier, funded by the court administrator’soffice. Feedback from these groups has been positive andparticipants have reported positive outcomes. The DrugCourt staff reports that the groups are particularly effectivein helping people connect with others in recovery, developan understanding of the recovery process, and becomewilling to consider the work required to sustain theirrecovery. The Drug Court and recovery community centerstaffs have collaborated on developing programming forparticipants, which includes peer recovery coaching.Peer Recovery Support WorkersHistorically sponsors from mutual-aid support programs(such as 12-step groups) who offered voluntary servicewithin communities of recovery were at one end of thespectrum while clinically focused addiction treatmentspecialists (certified addiction counselors, psychiatrists,psychologists, case managers, and social workers) wereat the other end. However, new roles have emerged tohelp bridge the gap between brief professional treatmentin a clinical or institutional setting and sustainable recoveryin the community. These peer recovery support workershelp individuals and families initiate, stabilize, and sustainrecovery. They have lived experience, meaning they havesuccessfully engaged in their own recovery with addiction,and are preferably alumni of Drug Courts.The peer recovery support worker builds a relationshipwith the participant through identification and trust andhas credibility based on mutual understanding. Part of thework of the peer recovery support worker is to help theDrug Court participant develop a recovery plan. Based onthe recovery capital assessment, the recovery plan outlinesthe person’s recovery goals. The peer recovery supportworker also helps people develop action plans to achievetheir goals, to articulate and visualize the kind of life theywould like to have in recovery, and to develop a roadmap toget there. They connect participants to recovery-supportiveresources that are instrumental to sustaining recovery(e.g., housing and employment) and serve as a liaison toformal and informal community supports, resources, andrecovery-supporting activities.Paid and volunteer peer recovery support workers go bysuch names as recovery coach, personal recovery assistants, orpeer support specialist (see Table 2). They can be found inrecovery community centers, jails, hospitals, child welfaresystems, in traditional treatment sites, and in the community.Drug Court Practitioner Fact Sheet 3

TABLE 2 Definition of RolesRoleDefinitionPeer or recovery coach A volunteer or paid person with personal experience goingthrough recoveryPeer recovery specialistPeer support specialist A guide and mentor who may have received training butnot necessarily formal educationPersonal recovery assistant A consultant with links to traditional professional servicesand support communitiesCounselor A licensed medical care professional with specialized educationCase manager A provider of traditional therapy and servicesSponsor A volunteer with personal experience going through recovery A person who is aligned with a 12-step recovery programrather than a professional treatment providerRecovery-Oriented Culturein Drug CourtsIn the Chittenden County Drug Court, the courtthat requires attendance in six to twelve peerrecovery coaching sessions, many participantscontinue to receive coaching after graduation(Vermont Recovery Network, 2013). The idea ofthe recovery community as a “holding area” tonurture and support recovery is not a new one,but has been formalized by the use of peer recoverysupport services and recovery community centers.These community-based and -driven supportsreinforce recovery by creating recovery culturalnorms, addressing relapse both before and when itoccurs, and providing safe spaces where recoverycan flourish.Recovery community centers are providing publicand visible spaces for recovery in an increasingnumber of communities. They engender civicengagement and leadership development. Theypromote advocacy and education about recoveryand are a welcoming place to bring together peoplein recovery, family members, friends, and a host ofcommunity stakeholders.4 NDCI: The Professional Services Branch of NADCPThese community-based supports and servicesare filling the gap between specialty treatmentand mutual-aid support groups. They are part ofgrowing network of institutions that are buildingrecovery-oriented communities and creating a newrecovery culture (see Figure 1).In another example, the Drug Courts in DauphinCounty, Pennsylvania, contract with the RASE(Recovery, Advocacy, Service, Empowerment)Project, a recovery community organization inHarrisburg, Pennsylvania, to provide weeklygroup sessions called Introduction to Recoveryfor participants. In Lancaster and CumberlandCounties, the organization sends volunteers inrecovery from its speakers bureau to share theirrecovery stories. The RASE Project has also assigneda peer recovery specialist (a state-certified andreimbursable service role) to attend court sessionstwice a month and provide support services toparticipants.A number of recovery community organizationshire Drug Court graduates. For example, in SouthCarolina, a drug court participant who completedthe 40-hour certified peer support specialist

Building Recovery-Oriented Systemsof Care for Drug Court Participantstraining is leading a women’s peer recovery group. Many ofthese organizations receive referrals for recovery coachingand recovery housing. Most have informal relationshipswith Drug Courts. Participants may be referred to therecovery community organization or recovery communitycenter for opportunities to socialize and volunteer. Thesepartnerships are reconnecting Drug Court participants withtheir communities as is demonstrated in an example fromConnecticut where two people referred by the Drug Courtwere awarded volunteer of the month by the ConnecticutCommunity for Addiction Recovery (CCAR).For Drug Court participants with a criminal history, theopportunity to be involved with a recovery communityorganization has proved vitally important. At Utah SupportAdvocates for Recovery Awareness (USARA) in Salt LakeFIGURE 1 Creating ecoverySchoolsSource: White, 2009a, 2009b; White et al., 2012City, participants can complete their community servicehours at their recovery community center. Because oftheir criminal histories, this center is one of the few placeswhere they can do this. The organization’s family resourcefacilitator helps families in the family Drug Court programin the juvenile courts. The facilitator works with parentswho have a substance use problem and are involved withthe Division of Child and Family Services to regain ormaintain custody of their children.In southeast Pennsylvania, PRO-ACT (PennsylvaniaRecovery Organization—Achieving Community Together)works with its Drug Courts by providing a certifiedrecovery specialist to each Drug Court participant to helpassess recovery capital and develop a resource recoveryplan to help participants enhance and strengthen theirrecovery. These specialists provide ongoing supportthrough each level of the Drug Court process either faceto face or through the use of telephonic recovery support.Family members and significant others receive a familyadvocate and participate in a family education program,which includes parenting classes. The parenting classes areattended by family and drug court participants togetherto strengthen family bonds and provide skill-buildingopportunities to enhance parent effectiveness. In addition,all Drug Court participants have access to Gateway toWork, an 8-session program to help individuals gain andmaintain satisfying employment.Recovery community organizations in rural communitiesalso have relationships with Drug Courts. The RecoveryWyoming Board of Directors includes the DUI/DrugCourt coordinator. Drug Court participants learn aboutthe organization’s recovery community center, peerrecovery support services, and opportunities for sobersocial activities. In Houston, the Center for Recovery andWellness Resources provides recovery coach services andall-recovery support groups to help participants on theirrecovery journey. They also transport individuals to eventsand services at the local recovery community center to getthem plugged into the recovery community. Faces andVoices of Recovery maintains a list of recovery communityorganizations on its Web site (see Resources at the end ofthis fact sheet).Drug Court Practitioner Fact Sheet 5

Building Recovery-OrientedSystems of CareRecovery-oriented systems of care make servicesand resources available for people to meet theirneeds. These systems build on the strengths andresilience of individuals, families, and communitiesto support responsibility for the person’s long-termrecovery, health, and wellness. Following are somekey components of recovery-oriented systems ofcare (White, 2009a, 2009b; White et al., 2012).The Foundation for a Recovery-OrientedSystem of Care Individuals and their families seeking help E ffective, quality addiction prevention, treatment,and peer and other recovery support services An organized recovery communityBuilding Blocks of Recovery-OrientedSystems of Care R ecovery residences: safe and sober peer-drivenhousing (e.g., Oxford House) Developing standards to assure quality A dvocacy to address increasing not-in-mybackyard (NIMBY) discrimination Legal assistance Primary health care and dental care E mployment: recovery-oriented employersand employment programs; job readiness andpreparation; and opportunities to volunteer andbuild work histories Financial stability Transportation including driver’s license E ducation: recovery GED programs; recoveryhigh schools; collegiate recovery programs; andcommunity colleges Child care R ecovery-oriented leisure and social activities(e.g., recovery music, recovery murals, recoverysocial events, sports venues, and recovery walks) C ivic engagement (e.g., working to endrestrictions on voting rights for people with acriminal justice history)6 NDCI: The Professional Services Branch of NADCPCommunities of Recovery Recovery community organizations Recovery community centers Peer recovery support services September Recovery Month events and rallies Recovery chat rooms Recovery apps for phones M utual-aid support groups(e.g., AA, NA, MA, CA, Smart Recovery) Recovery-oriented employers T reatment and Drug Court alumni andgraduate associations R ecovery high schools and collegiaterecovery communities Recovery media and entertainment The FIX, Radio Recovery, recovery cruises Recovery professional organizations Recovery ministriesDrug Courts can take the first steps toward buildingrecovery-oriented systems of care for participants bybringing in people in recovery to programs, offeringhope, and inviting participants to build their ownrecovery journeys. They can help organize andencourage participants to be a part of communitybased recovery celebrations throughout the yearand during September’s National Recovery Monthobservances. The Recovery Self-Assessment Toolbelow is a comprehensive list of practical steps thatDrug Courts can take to assess and address theirreadiness to bridge the gap between the treatmentand recovery communities.Recovery-Oriented Drug Courts:A Self-Assessment ToolUse this tool to think about the ways that yourprogram is building bridges to the recoverycommunity and providing opportunities forindividuals to achieve and sustain their recoveryfrom addiction. A recovery orientation will increaseyour ability to be successful in getting individuals thesupport they need while they are in your programand as they transition into the community.

Building Recovery-Oriented Systemsof Care for Drug Court ParticipantsCHECK LISTLEADERSHIPWe incorporate a vision of long-term recovery for participants and their families in the Drug Court’s mission.Our advisory board includes Drug Court graduates who are in long-term recovery and representatives of therecovery community.Our staff members and volunteers include people in long-term recovery and their family.Our staff members are involved in activities that address the social stigma and other forms of discrimination facedby people in recovery who have criminal records.Our staff members receive ongoing specific training on addiction and recovery policies and practices, includingupdates on research, support services, community organizations, and resources, and attend open 12-step meetings.Our staff members are required to be familiar and experienced with a variety of mutual-aid support groups(e.g., 12-step programs, Smart Recovery, Double Trouble).We encourage opportunities to share stories of long-term recovery.FAMILY AND SUPPORTER INVOLVEMENTWe provide an information packet about Drug Court and resources for help.When the participant agrees, we involve family in the development of the recovery plan.We provide added incentives for individuals who attend family counseling.We encourage family members to participate in recovery community organizations, recovery community centeractivities, family mutual-aid groups, and other supports.When the participant agrees, we encourage family to attend Drug Court sessions and participate in meetings,barbecues, outings, and other sober social events.When the participant agrees, we involve family in progress sessions that are scheduled before graduation.SERVICE PHILOSOPHYWe educate all participants, family members, and supporters about the recovery community.We embrace the importance of self-determination and choice in planning a program for long-term recovery,which includes goal development, a menu of supports and services, and desired outcomes.We require each participant to develop a recovery plan before entering the final phase of Drug Court.We embrace the importance of matching and understanding individual participants’ characteristics with the methodsand services that will best help them achieve and sustain their recovery.COMMUNITY LINKAGESWe offer a volunteer program that includes people in long-term recovery.We have an alumni program that includes participants and their families.We provide and maintain a comprehensive listing of diverse mutual-aid supports.We provide and maintain linkages with secular and faith-based recovery support resources.We offer and support alcohol- and drug-free social activities.We provide and maintain linkages to safe, sober, and structured housing opportunities.We provide and maintain linkages to recovery friendly jobs, employers, and training.We include recovery-oriented questions in the exit questionnaire and all program evaluation for graduates.We monitor and assess the percentage of participants who are linked to the recovery communityprior to graduation.Drug Court Practitioner Fact Sheet 7

ResourcesReferencesFaces & Voices of Recoverywww.facesandvoicesofrecovery.orgKelly, J.F., Dow, J.F., & Westerhoff, C. (2010). Does ourchoice of substance-related terms influence perceptionsof treatment need? An empirical investigation with twocommonly used terms, Journal of Drug Issues, 40(4),805–818.National Alliance of Recovery Residencesnarronline.orgOxford Housewww.oxfordhouse.orgRecovery Research Institutewww.recoveryanswers.orgSubstance Abuse and Mental Health ServicesAdministration (SAMHSA) Recovery Supportsamhsa.gov/recovery/ Bringing Recovery Support Services toScale Technical Assistance Centerbeta.samhsa.gov/brss-tacs Recovery to px Recovery Month—recoverymonth.govRecovery Research Institute. (2012). Recovery. Retrieved ion-ary/recovery/Rondo, J., and Feliz, J. (2012). Survey: Ten percent ofAmerican adults report being in recovery from substanceabuse or addiction. Retrieved from .cfmVermont Recovery Network. (2013). Helping peopletake responsibility for recovery. Retrieved from https://vtrecoverynetwork.org/PDF/Take Responsibility forRecovery.pdfWhite, W.L. (2009a). Peer-based addiction recovery support:History, theory, practice, and scientific evaluation. Chicago:Great Lakes Addiction Technology Transfer Center.Copublished by the Philadelphia Department of BehavioralHealth and Mental Retardation Services.White, W.L. (2009b). The mobilization of communityresources to support long-term addiction recovery. Journalof Substance Abuse Treatment, 36(2), 146–158.White, W.L., Kelly, J.F., & Roth, J.D. (2012). New addictionrecovery support institutions: Mobilizing support beyondprofessional addiction treatment and recovery mutual aid.Journal of Groups in Addiction & Recovery, 7(2-4), 297–317.The Professional Services Branch of NADCP1029 N. Royal Street, Suite 201Alexandria, VA 22314Tel: 703.575.9400Fax: 703.575.9402

Betty Ford Institute Consensus Panel 2006 A voluntarily maintained lifestyle characterized by sobriety, . A person who is aligned with a 12-step recovery program . Drug Court Practitioner Fact Sheet 5 uilding Recovery-Oriented Systems of Care for Drug Court Participants training is leading a womens pe' er recovery group. Many of