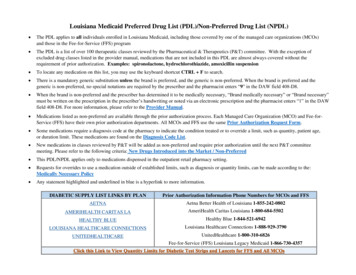

Transcription

theLOUISIANAJUVENILEDEFENDERTRIAL PRACTICEMANUALpublished byjuvenile justice project of louisianasouthern juvenile defender center

theLOUISIANAJUVENILEDEFENDERTRIAL PRACTICEMANUALpublished byThe Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana& The Southern Juvenile Defender Centerwith funding suppor t fromThe Open Society Institute

The LouisianaJuvenile DefendersTrial Practice Manualwritten byL. Kate Mitchell— edited by—Derwyn D. BuntonGabriella CelesteBarry GerharzAssociate DirectorJuvenile JusticeProject of LouisianaExecutive DirectorAlliance of Child CaringService ProvidersStaff AttorneyJuvenile JusticeProject of LouisianaHector LinaresIlona Prieto PicouDavid UtterSpecial Education Law FellowSouthern Poverty Law CenterRecovery CoordinatorOrleans ParishJuvenile CourtExecutive DirectorJuvenile JusticeProject of LouisianaJason WilliamsonStaff AttorneyJuvenile JusticeProject of Louisiana

the louisiana juveniledefender trial practice manualFirst PrintingPublished by the Juvenile Justice Project ofLouisiana and the Southern Juvenile DefenderCenter, A Project of the Southern Poverty LawCenter.Copyright 2007All rights reserved. No part of this book may bereproduced in any form or by electronic or mechanical means including information storage andretrieval systems without written permission fromthe Juvenile Justice Project of Louisiana. the Louisiana Juvenile Defender Trial Practice Manual

ContentsPART IJuvenile Delinquency Court: An OverviewChapter 12424242628292931THE HISTORY AND PURPOSE OF JUVENILE COURTI. The Origin of the Juvenile CourtA. The Doctrine of Parens PatriaeB. The Creation of a Juvenile CourtC. The Evolution of Juvenile CourtD. The Juvenile Court Becomes More Criminal in NatureII. Juvenile Court in LouisianaIII. Conclusionchapter 232333435353637384040404040The Role Of Defense Counsel In Juvenile CourtI. The Role Of A Juvenile DefenderII. Ethical Obligations Of A Juvenile DefenderA. Competent RepresentationB. CommunicationC. Client-Centered RepresentationD. ConfidentialityE. ConflictsF. Advocacy1. Diligence2. Zealousness3. Expeditiousness4. Systemic ActivismChapter 342 Understanding the Juvenile Client:An Overview of Adolescent Development42I. Adolescent Development in the Law46II. Developmental Characteristics of Children and Youth47A. Age47B. Neurological Development48C. Cognitive/Intellectual Development: How Children and Youth Think491. Minimizing Dangertable of contents

49505050515152525253CHAPTER 4 65656666666768682. Inability to Anticipate Consequences3. Inability to Consider Multiple Choices4. Reacting to Perceived ThreatD. Physical DevelopmentE. Identity/IndependenceF. Morals1. Focus on Fairness2. Perceived Lack of Remorse3. LoyaltyG. Unresolved TraumaA SUMMARY OF THE LOUISIANA JUVENILE COURT PROCESSI. Entry Into The Juvenile Justice System: Arrest And CustodyA. ArrestB. Custody Pursuant to Court OrderII. Pre-Adjudication ProceduresA. PetitionB. Answer1. Insanity PleaC. TransferD. Waiver to Criminal Court JurisdictionE. Pre-Adjudication Motions for Relief1. Discovery2. Bills of Particulars3. Medical, Sensory, Psychological and Psychiatric ExaminationsF. DiversionG. Competency to ProceedIII. AdjudicationIV. Post-AdjudicationA. Post-Adjudication Motions for Relief1. Motion to Vacate Adjudication2. Motion for a New TrialB. Disposition1. Deferred Dispositional Agreement2. Predisposition Reports and Evaluations3. Disposition Hearing4. Disclosure of Predisposition Report to Other AgenciesC. Post-Disposition1. Progress Reports2. Required Reviews—Mental Health Commitment3. Modification of Disposition4. Probation RevocationD. Appeal1. Notice of Appealthe Louisiana Juvenile Defender Trial Practice Manual

6868chapter 48586Chapter 68888899090919191922. Discretionary Review of AppealE. ExpungementTHE constitutional rights OF YOUTHIN DELINQUENCY PROCEEDINGSI. OverviewII. Due Process And The Fundamental Fairness StandardIII. Right to Notice of ChargesIV. Right to CounselA. Right to Counsel—InterrogationB. Right to Counsel—SentencingC. Right to Counsel—Post-AdjudicationV. Right to Fair TrialA. The Presumption of InnocenceB. The Right to a Speedy TrialC. No Juvenile Shall be Compelled to Give Evidence Against HerselfD. The Right to Confront and Cross-Examine WitnessesE. The Right to Compel the Attendance of WitnessesF. The Right to Present a DefenseG. The Right to TestifyVI. Ancillary Constitutional RightsA. Rights at Arrest/InterrogationB. Right to BailC. AppealD. The Right to Writ of Habeas CorpusE. Access to the CourtsF. Right to TreatmentVII. Waiver of Constitutional RightsA. Waiver of the Right to CounselB. Waiver of Counsel—InterrogationC. Waiver of Constitutional Rights: Adjudication, Confrontation,Self-IncriminationSpecial education ADVOCACYAND DELINQUENCY REPRESENTATIONI. Determining Whether Your Client has a DisabilityA. Acquiring RecordsB. Common Disabling Conditions1. Learning Disabilities2. Emotional or Behavioral Disorders3. Mental Disability/Mental Retardation4. Other Health ImpairmentII. Legal Protections for Children with Disabilitiestable of contents

10810911011011111111211311311311411511611610A. Sources of Laws Protecting the Rights of Children with Disabilities1. Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA)2. State Laws and Regulations3. School District Codes of Conduct and Student Handbooks4. Other Federal SourcesB. Substantive Protections for a Free and Appropriate Public Education1. Educational Benefit2. Related Services3. Least Restrictive Environment4. Transition ServicesIII. Special Education AdvocacyA. Special Considerations When Providing Special Education Advocacyto a Delinquency ClientB. Identifying a Child for Special Education Services1. Requesting an Evaluation2. Independent EvaluationsC. IEP MeetingsD. Filing for a Due Process HearingE. Judicial Review of a Due Process Hearing DecisionF. Mediation and Other Procedural AvenuesG. RemediesIV. Advocating for a Disabled Client in School Discipline MattersA. The 10-Day RuleB. The 45-Day ExceptionC. Services During Removals and Interim Alternative Educational SettingsD. Other Procedures Involving Disciplinary Removals1. Manifestation Determination Review2. Functional Behavioral Assessments and Behavior Intervention PlansE. Disciplinary Protections for Children Not Yet Identified as DisabledV. Special Education Advocacy in the Delinquency SystemA. A Sampling of Theories and Strategies Availableto the Delinquency Defense AttorneyB. Motion to SuppressC. Motion to DismissD. Advocating for Special Education Services at DispositionVI. Conclusionthe Louisiana Juvenile Defender Trial Practice Manual

PART IIThe Practice: Representing Children And Youth At EveryStage Of The ProcessCHAPTER 7120 DEVELOPING AN ATTORNEY-CLIENT RELATIONSHIPWITH A CHILD OR ADOLESCENT120 I. Building a Rapport with your Client120A. The Initial Interview123B. Getting to Know Your Client1231. Educational History and Developmental Disabilities1242. Mental Health Needs1243. Race and Gender1244. Competency125 II. Interviewing Skills: Strategies for Interviewing Children and Adolescents125A. Differences in the Cognitive Capacities of Adults and AdolescentsCan Pose Challenges in an Interview126B. Strategies for Successful Interviewing126C. Tips for Interviewing Adolescents127D. Special Skills and Techniques1271. How to Interview a Teenager with an “Attitude”1282. How to Defuse an Angry Young Person During an Interview1283. Special Considerations When Interviewing a Young Client129 III. ConclusionCHAPTER 8130 DEVELOPING A RELATIONSHIP WITH YOUR CLIENT’S PARENTS ORGUARDIAN130 I. The Importance of a Positive Relationship withyour Young Client’s Parents131A. Developing a Relationship with Your Client’s Parents132B. The Initial Parent Interview133 II. Potential Conflicts in Working with Parents135 III. ConclusionChapter 9136136137138139139139139Advocacy Starts at the Beginning: arrest and custodyI. Entry into the SystemA. ArrestB. Taking into Custody with Court OrderC. Service of Petition and SummonsII. Procedure after Arrest or Service of Petition and SummonsA. Police Practices Following Arrest1. Procedure After Arrest Without Warranttable of contents11

0151152152152152152152153153153154154155156CHAPTER 10122. Procedure After Arrest with a Warrant or Court Order3. Identification ProceduresB. Rights at Arrest1. Judicial Review of Probable Cause2. Role of Defense Counsel at ArrestIII. DetentionA. The Authority to DetainB. The Continued Custody Hearing1. Rights at the Continued Custody Hearing2. Role of Defense Counsel at the Continued Custody Hearing3. Preparation for the Hearing4. The Hearing and Probable CauseC. The Right to Bail1. Advocating for a Low Bail2. Types of Bail3. Modification of Bail4. Release OrdersD. Motion to ReleaseE. Appeal of Detention DecisionsIV. Practice TipsA. Effective Arguments if it is Alleged that the Clientwill Likely Fail to Appear for Court1. Secure adult support2. Provide evidence that your client is not likely to miss court3. Address previous failures to appear4. Address any allegations of an unstable living situation5. Address fears or allegations that the youth will run6. Present an alternative to the detention plan that will make it more likely thatyour client will return to court and stay out of trouble pending adjudication7. Contradict any assertions that your client is dangerousB. Address Problems with the Detention CenterC. Alternatives to DetentionV. Conclusion157 MENTAL INCAPACITY TO PROCEED157 I. What is Competency and Mental Capacity?160 II. Assessing Whether your Client is Competent162 III. Ethical Implications of Raising Competency163 IV. Procedure Upon Raising Competency164A. Mental Examinations1641. Sanity Commission1652. Sanity Commission Report166B. Determination of Mental Capacity to Proceed169 V. Practice Tipsthe Louisiana Juvenile Defender Trial Practice Manual

169170171171173A. Challenging Problematic Court PracticesB. Working with the Sanity CommissionC. Preparing Your ClientD. Preparing for the Sanity HearingVI. ConclusionCHAPTER 11174174174175175176177179180PRE-ADJUDICATION PROCEDURESI. Petition and SummonsA. Form of the PetitionB. Amendments to the PetitionC. Service of the PetitionD. SummonsII. AnswerIII. Insanity DefenseIV. DiversionCHAPTER 12182 CASE PREPARATION182 I. Developing A Theory of the Case182A. Legal Research183B. The Theory of the Case183 II. Discovery184A. Discovery Requests1841. The Right to Discovery184a. The Right to Exculpatory Evidence185b. The State Must Disclose More than the Prosecutor’s File186c. Discovery Must Be Timely Disclosed186d. Good Faith Is No Excuse1862. Louisiana Discovery Guidelines1883. Sanctions1894. Responding to Discovery Requests189B. Subpoenas and Subpoenas Duces Tecum1891. Subpoenas1902. Subpoenas Duces Tecum190 III. Investigation191A. Sources of Information for the Investigation192B. Records Collection and Public Records Requests1921. Courthouse Searches1932. State Public Records Requests1933. Federal Freedom of Information Act Requests1944. Office of Community Services Records Requests1945. Office of Youth Development Records Requests194 IV. Witness Development195A. Lay Witnessestable of contents13

CHAPTER 13195195196197197B. Hostile WitnessesC. Expert WitnessesD. Your Client as a WitnessV. Client InterviewsVI. ADJUDICATION MOTIONS AND HEARINGSI. Pre-adjudication Motions GenerallyII. Motion for Change of VenueIII. Motion for RecusalIV. Motion for DiscoveryA. Motion for Bill of ParticularsB. Additional Discovery Motions1. Motion for Additional Discovery2. Motion for In Camera Inspection3. Motion to Quash Subpoena4. Motion for a List of State Witnesses5. Motion for Disclosure of Plea Agreementsand Preferential Agreements with Witnesses6. Motion for Disclosure of Mental Health Recordsof Complaining Witnesses7. Motion for Funds to Hire Expert Witnesses8. Motion for a Free Transcript9. Motion for Discovery and Inspection of Scientific Tests and Reports10. Motion for Funds to Hire a Private InvestigatorC. Failure to Comply With Discovery:When the Prosecutor Fails to Timely Respond to Discovery Requests1. Motion to Compel2. Motion to Show Cause3. Motion for SanctionsV. Motions to DismissVI. Motion for Severance of CausesVII. Motions to SuppressA. Motion to Suppress Physical EvidenceB. Motion to Suppress a Confession or Statement1. Suppression of Statements When No Miranda Warning Was Given2. Knowing, Intelligent and Voluntary Waiver of Rights3. Suppression of Statements Made After Request for CounselC. Motion to Suppress an IdentificationVIII. Miscellaneous Procedural MotionsA. Motion for ContinuanceB. Motion for Extension of Time to File Pre-Adjudicatory MotionsC. Creative Motions PracticeIX. Supervisory Writs on Pre-adjudication 0920921121121221221221321314the Louisiana Juvenile Defender Trial Practice Manual

CHAPTER 227TRANSFERS TO ADULT COURTI. Tragic Consequences of TransferII. How a Child may end up in Adult Criminal CourtA. Legislative WaiverB. Prosecutorial WaiverC. Judicial Waiver by Transfer HearingIII. The Article 857 Transfer ProcessA. Transfer Decision Is of Constitutional Magnitude: Due Process RequiredB. Who Is Eligible for a Transfer?C. Notice of Intent to Seek TransferD. State’s Burden of Proof and the Everfield FactorsIV. Representing a Child Facing TransferA. Developing a Theory of the Child and CaseB. Preparation and InvestigationV. The Transfer HearingA. Probable Cause DeterminationB. “Clear and Convincing” Proof of “No SubstantialOpportunity for Rehabilitation”227C. Role of Defense Counsel in the Hearing: Showing Hope for Rehabilitation229D. Guidelines for the Juvenile Court & Required Findings229 VI. Seeking a Writ on a Transfer Decision230 VII. ConclusionChapter 239240240240240AdjudicationI. Pleas and NegotiationsA. Assessing the Benefits of a PleaB. Plea Offers from the ProsecutionC. Your Client Expresses an Interest in Making an AdmissionD. Preparing Your Client to Enter an Admission in CourtII. Confidentiality and Sequestration of WitnessesA. Confidentiality of Juvenile Court ProceedingsB. Sequestration of WitnessesIII. Rules of EvidenceIV. Presentation of Evidence—Getting it in the RecordA. Opening StatementB. Presentation of WitnessesC. Cross-ExaminationD. Closing ArgumentV. Adjudication OrderA. Finding of DelinquencyB. Families in Need of Services (“FINS”) AdjudicationC. Dismissal of the PetitionVI. Post-Adjudication Motions—Vacating Adjudication OrderA. Motion to Vacate the Adjudicationtable of contents15

241241Chapter 16B. Motion for a New Adjudication HearingVII. Preserving the Right to Appeal242 Disposition242 I. Pre-Disposition Preparation242A. Securing Additional Documentation243B. Pre-Disposition Investigation and Evaluations244C. Securing and Preparing Witnesses for the Disposition Hearing245D. Negotiating with the Prosecutor and the Office of Youth Development245E. Counseling Client and Family Regarding Disposition Alternatives245F. Preparation of an Alternative Dispositional Plan247G. Deferred Dispositional Agreement248 II. Disposition Hearing248A. Disposition Procedures249B. Rules of Evidence During Disposition Hearing249C. Presentation of Treatment Plan249D. Dispositional Alternatives Available to the Court2491. Disposition After Adjudication for a Felony-Grade Delinquent Act2512. Disposition Under Article 897.1: Juvenile Life2523. Disposition After Adjudication for aMisdemeanor-Grade Delinquent Act2534. General Dispositional Guidelines254E. Disposition After Finding of Insanity254F. Disposition After Adjudication as Family in Need of Services256G. Commitment to Mental Institution256H. Care and Treatment by the Office of Youth Development (“OYD”)PART IIIPOST-DISPOSITION ADVOCACYChapter 1716260 Juvenile Rights in Secure Care andthe Importance of Ongoing Advocacy260 I. Constitutional Rights of Youth in Secure Custody262A. The Right to Rehabilitation262B. The Right to Humane Conditions of Confinement262C. The Right to Personal Safety and Protection from Harm263D. The Right to Medical and Mental Health Care264 II. Educational Rights While Incarcerated265 III. OYD Policies and Procedures265A. Assessment and Placement265B. Custody Classificationthe Louisiana Juvenile Defender Trial Practice Manual

266267C. Administrative Review Procedure (“ARP”)D. Project Zero Tolerance (“PZT”)Chapter 18269 Modification of Disposition269 I. Right to Modification under Law269A. Modification Procedure270B. Mental Health Commitment and Modification270 II. Grounds for Modification272A. Progress in Secure Care/Rehabilitation Complete273B. Abuse and Other Conditions Problems274C. Inappropriate Placement275D. Lack of Rehabilitative Treatment275E. Benefit of Parole and Aftercare Prior to Outright Release276 III. Investigation and Preparation276A. Interviewing the Client277B. Interviewing Counselors, Probation Officers, and Teachers278C. Interviewing Family278D. Collecting Records279E. Considering Expert Assistance279F. Talking with State Representatives in Advance of Hearing279 IV. Preparing a Release Plan280 V. Modification Hearing280A. Challenging Suitability of Current Placement280B. Presenting the Plan for Release or Modification280C. Countering Opposition from District Attorney or OYD281D. Weaving the Factual Basis into the Law281 VI. Effect of Modification decision282A. Supervisory Writ282B. Continued Advocacy at Review Dates282C. Filing Additional Motions for ModificationChapter 19284 Defending AGAINST a Motion forRevocation of Probation or Parole284 I. Revocation Procedure286 II. Consequences if a Violation of Probation or Parole is FoundChapter 20288 Appeals and Extraordinary Writs288 I. Appellate Practice288A. Appeals Generally2881. Right to Appeal2882. Final Judgment2883. Jurisdictiontable of contents17

9930030030030130130130230230230318B. Perfecting an Appeal1. Deadlines2. Form3. Notice of Appeal4. Return Date5. Preparation of the RecordC. Effect of Filing the AppealD. Procedures Before the Appellate Courts1. Scope of Review2. Request for Oral Argument3. Requirements for Briefsa) Filing Timelines and Number of Copiesb) Preparation of Briefsc) Specific Requirements for Appellant’s Briefd) Specific Requirements for Appellee’s Response Briefe) Appellant’s Reply Brieff) Case Citation Requirementsg) Sanctions4. Application for RehearingII. Supervisory Jurisdiction and Review: Writ PracticeA. Procedure for Requesting a Supervisory WritB. Application for Writ1. Stay of Proceedings Pending Decision2. Expedited Consideration3. Contents of Writ ApplicationIII. Writ of Habeas CorpusA. Habeas GenerallyB. Grounds for ReliefC. VenueD. Burdens of ProofE. FormF. Procedure1. Answer2. Hearing3. JudgmentG. Writs and Appeals from Habeas DecisionsIV. Writ of MandamusV. Post-conviction Procedures in Delinquency MattersA. Post-Conviction Relief GenerallyB. Grounds for ReliefC. VenueD. The Evidentiary HearingE. Application and PetitionF. Time Limitsthe Louisiana Juvenile Defender Trial Practice Manual

Chapter 21304 Expungement of Records304 I. Eligibility for Expungement305 II. Process for Obtaining Expungement of Records305 III. Effect of Expungement of Records305A. Order of Expungement Regarding Court RecordsB. Order of Expungement Regarding Agency RecordsAPPENDIXAppendix A308 AUTHORIZATION TO DISCLOSE PROTECTED HEALTH AND OTHERINFORMATION (HIPAA)Appendix B310client Interview QuestionsAppendix C315319Parent Interview QuestionsAcknowledgmentstable of contents19

If we don’t stand up for children, thenwe don’t stand up for much.— marian wright edelman

PART IJuvenileDelinquencyCourt:An Overview

Chapter 1THE HISTORY AND PURPOSE OF JUVENILE COURTRepresenting children and youth in delinquency proceedings is both rewarding andchallenging because of the unique nature of juvenile court. The reward lies in thepromise that, with the proper guidance, treatment and care, children can becomesuccessful adults without bearing the stigma that often follows from an adult conviction. The challenge lies in the conflicting philosophies of juvenile court: zealous representation of the child versus the best interest of the child. This conflict can presenta barrier to effective representation by placing pressure on defenders to both advocate for their client’s best interests and personal interests. To assist defenders indeveloping an effective juvenile practice, this chapter presents an overview of thehistory and purpose of juvenile court and the development of Louisiana’s juvenilejustice system.I. The Origin of the Juvenile CourtA. The Doctrine of Parens PatriaeThe doctrine of parens patriae is taken from chancery practice to describe the powerof the state to act in place of the parent for the purpose of protecting the property interests and the person of a child. The doctrine provides for the state’s role asguardian to protect a child who cannot protect herself. The United States SupremeCourt discussed the doctrine in In re Gault, its seminal case regarding juvenile dueprocess rights:The right of the state, as parens patriae, to deny to the child proceduralrights available to his elders was elaborated by the assertion that a child,unlike an adult, has a right “not to liberty but to custody.” He can bemade to attorn to his parents, to go to school, etc. If his parents defaultin effectively performing their custodial functions—that is, if the child is“delinquent”—the state may intervene. In doing so, it does not deprive thechild of any rights, because he has none. It merely provides the “custody”to which the child is entitled. The Court again addressed parens patriae in Schall v. Martin , stating: Gabriella Celeste & Patricia Puritz, eds., The Children Left Behind: An Assessment of Access to Counsel and Quality of RepresenDelinquency Proceedings in Louisiana, American Bar Association (June 2001). In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1, 16 (1967). Id. at 17. Schall v. Martin, 467 U.S. 253, 265 (1984).tation in24the Louisiana Juvenile Defender Trial Practice Manual

CHAPTER ONE the history and purpose of juvenile courtChildren, by definition, are not assumed to have the capacity to takecare of themselves. They are assumed to be subject to the control oftheir parents, and if parental control falters, the State must play its partas parens patriae. In this respect, the juvenile’s liberty interest may, inappropriate circumstances, be subordinated to the State’s “parens patriaeinterest in preserving and promoting the welfare of the child.” Prior to acceptance of the parens patriae doctrine, delinquent behavior wasaddressed within the family. Children generally worked within the family unit, andthe family was responsible for providing discipline, education and socialization. Poor children were often sent to work with other families as apprentices and indentured servants, and the apprentice families became responsible for the children inloco parentis, or in the place of the natural parent. The industrial revolution changed the labor system and displaced families fromtheir land and resulted in migration to urban centers. These changes in economicstructure brought poverty, weakened family ties and led to an increase in delinquentbehavior. Children and youth who committed crimes began to be sent to adult jailsand workhouses.10During the 1800s, the first juvenile prisons were created by a group of philanthropists called the Society for the Prevention of Pauperism.11 The group believed thatincarcerating children and youth in adult jails would worsen their behavior and thatjudges might acquit children and youth to avoid incarcerating them in abhorrentadult jail conditions.12The new prisons for juvenile offenders were called Houses of Refuge and weredesigned as educational facilities.13 The first House of Refuge opened in New York in1825.14 Houses of Refuge soon spread across the country and became residences fordelinquent, neglected and dependent children.15 The traditional view that the familywould provide discipline, education and socialization was replaced with the ideathat the state would, as “common guardian of the community,” take the place of thechild’s natural parents.16 Children whose parents could not provide for them becauseof poverty or unemployment or were simply “not suitable” were placed in Houses ofRefuge.17 Id. at 266. Barry Krisberg & James F. Austin, Reinventing Juvenile Justice 14 (1993). Id. at 13. Id. at 14–15. Id. at 15–16.10 Id. at 17.11 Id. at 24.12 Id. at 17.13 Id.14 Id.15 Id. at 17.16 Id. at 18 (emphasis added).17 Id.part one Juvenile delinquency court: an overview25

By the mid-1800s, state and municipal governments began taking over the administration of institutions for juvenile delinquents.18 By the end of the century, Houses ofRefuge evolved into reformatories.19 Even though reformatories dominated the landscape of juvenile delinquency prevention at the time, there were reformers who didnot believe in the institutionalization of children. One reformer, John Augustus, ashoe cobbler in Boston, supervised children and youth who were released by thecourt on bail.20 Augustus paid court costs, provided clothing and shelter and tried tofind the children jobs in the community.21 In essence, Augustus was one of the firstprobation officers.B. The Creation of a Juvenile CourtThe first juvenile court was created during the Progressive Era, a time of major socialand structural change from the late 1800s to the early 1900s.22 At the time, Houses ofRefuge and reformatories had been available for decades, yet delinquency continuedto rise.23 There was growing doubt about the success of the reformatories in reducing delinquency, and courts began to question the unlimited use of the parens patriaedoctrine without providing constitutional protections.24Illinois created the first juvenile court in 189925 because the state had almost no institutions for the care of delinquent children and youth.26 The Illinois Juvenile CourtAct extended the parens patriae philosophy of the reform schools to the court system,thereby giving a special juvenile court jurisdiction over neglected, dependent anddelinquent children under the age of 16.27 The definition of delinquency was broad,encompassing a violation of any state law, city ordinance or village ordinance.28 Thecourt was given jurisdiction over any child or youth who was incorrigible, truant, orwho lacked the proper parental supervision.29 The Act also established the following: a rehabilitative purpose; a policy of confidentiality for records of the court to minimize stigma; separation of juveniles from adults when incarcerated orinstitutionalized; absolute prohibition against the detention of children under 12 in jails;18 Id. at 23.19 Robert E. Shepherd, Jr., Still Seeking the Promise of Gault: Juveniles and the Right to Counsel, ABA Criminal Justice Magazine,Summer 2003, at 23.20 Id. at 23.21 Id.22 Id. at 27.23 Id. at 29.24 Id.25 In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1, 14 (1967).26 Krisberg & Austin, supra note 6, at 29.27 Shepherd, supra note 19, at 2.28 Krisberg & Austin, supra note 6, at 30.29 Id.26the Louisiana Juvenile Defender Trial Practice Manual

procedural informality within the court. 30CHAPTER ONE the history and purpose of juvenile courtThe new Illinois juvenile court existed alongside the criminal court, but was a totallydifferent institution.31 The court, like other early juvenile courts, allowed the state totake on the role of guardian through parens patriae.32 Parens patriae dictated that proceedings in juvenile court be informal and civil in nature, rather than criminal. Civilproceedings allowed a judge to consider a broad range of information about the childseparate and apart from the actual offense and gave the courts more authority andsupervision over a child.33 Juvenile courts did not ascertain whether the child was“guilty” or “innocent,” but “[w]hat is he, how has he become what he is, and what hadbest be done in his interest and in the interest of the state to save him from a downward career.”34The juvenile court model spread across the nation and by 1909, 10 states had established children’s courts,35 including Louisiana.30 Shepherd, supra note 19, at 2.31 Id. at 23.32 Juvenile Justice FYI, Information on the History of America’s Juvenile Justice System, www.juvenilejusticefyi.com/history ofjuvenile justice.html (last visited Feb. 5, 2007).33 Id.34 In re Gault, 387 U.S. 1, 15 (1967).35 Krisberg & Austin, supra note 6, at 30.part one Juvenile delinquency court: an overview27

Under our Constitution, the condition of beinga boy does not justify a kangaroo court.36C. The Evolution of Juvenile CourtThe juvenile court functioned for nearly 70 years with little constitutional oversightand, except for a few jurisdictions, without the involvement of lawyers.37 However,in 1967, the United States Supreme Court decided In Re Gault, finding that under theguise of parens patriae, juvenile courts exercised unbridled and often arbitrary discretion over children in the juvenile justice system and that without constitutionalprotection, the juvenile courts were not achieving their purported rehabilitative goal.38The Court stated:The absence of substantive standards has not necessarily meant thatchildren receive careful, compassionate, individualized treatment. Theabsence of procedural rules based upon constitutional principle has notalways produced fair, efficient, and effective procedures. Departuresfrom established principle

183 II. Discovery 184 A. Discovery Requests 184 1. The Right to Discovery 184 a. The Right to Exculpatory Evidence 185 b. The State Must Disclose More than the Prosecutor's File 186 c. Discovery Must Be Timely Disclosed 186 d. Good Faith Is No Excuse 186 2. Louisiana Discovery Guidelines 188 3. Sanctions 189 4. Responding to Discovery Requests