Transcription

Capital Raising in the U.S.: An Analysis of the Market forUnregistered Securities Offerings, 2009‐20171AUGUST 2018SCOTT BAUGUESS, RACHITA GULLAPALLI, AND VLADIMIR IVANOVDivision of Economic and Risk Analysis (DERA)U.S. Securities and Exchange CommissionABSTRACTCapital formation through private placement of securities has increased substantially since thethe 2008 global financial crisis. During recent years, amounts raised through unregisteredsecurities offerings have outpaced the level of capital formation through registered securitiesofferings, and totaled more than 3.0 trillion during 2017. In this analysis, we provide insightsinto a large segment of the unregistered securities market2: offerings conducted in reliance onRegulation D of the Securities Act. Using information collected from Form D filings, this studyprovides a detailed examination of offering characteristics, including the types of issuers,investors, and financial intermediaries that participate in the offerings. As part of theexamination, we analyze the new and amended exemptions created pursuant to the JumpstartOur Business Startups Act of 2012 (“JOBS Act”) – the new Rule 506(c) exemption which becameeffective in September 2013 and allows general solicitation and general advertising, changingalmost 80 years of regulatory practice, the amended Regulation A which became effective June19, 2015 and the new Regulation Crowdfunding that became effective May 16, 2016. We alsoprovide some perspective on the state of competition and potential regulatory burden inalternate capital markets by analyzing the level of activity among the various registered andunregistered offering alternatives.1Research assistance provided by Daniel Bresler. The U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission, as a matter ofpolicy, disclaims responsibility for any private publication or statement of any of its employees.The views expressed herein are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of the Commission orof the author’s colleagues on the staff of the Commission.This study was prepared for Chyhe Becker, Acting Director of DERA and Acting Chief Economist, and is a follow‐upto a study conducted in 2015, which provided an analysis of capital raised through unregistered offerings for theperiod 2009‐2014. See Scott Bauguess, Rachita Gullapalli and Vladimir Ivanov, Capital Raising in the U.S.: AnAnalysis of the Market for Unregistered Securities Offerings, 2009‐2016 (October 2015) (the “2015 UnregisteredOfferings Study”), available at: pers/30oct15 white unregistered offering.html.The information in this study may be particularly useful in assessing the potential need for current or futurerulemaking activity. This analysis is not intended to inform the Commission about compliance with or enforcementof federal securities laws.2As used throughout the study, the term “market” refers to capital markets in general, and, where discussed in thecontext of a specific rule, relates to the provisions of the relevant exemption or safe harbor.1

SUMMARY OF MAIN FINDINGS In 2017, there were 37,785 Regulation D offerings reported on Form D filings,accounting for more than 1.8 trillion raised in new capital. Issuers in non‐financial industries3 reported raising 105 billion during 2017. Amongfinancial issuers, hedge funds reported raising 382 billion and private equity funds 582 billion, while financial issuers that are not pooled investment funds reported 72billion during 2017 and 570 billion during the 2009‐2017 period. Foreign issuers accounted for approximately 22% of the total amount reported soldduring 2017. Most foreign issuers are firms from Canada, Cayman Islands, and UnitedKingdom. During 2009‐2017, Rules 506(b) and 506(c) account for 99.9% of the amounts reportedsold through Regulation D, including 93% of capital raised in offerings with maximumoffer size of 1 million and 98% of capital raised below the amended Rule 504 offeringlimit threshold ( 5 million), suggesting that issuers continue to value the preemption ofstate securities laws provided for offerings conducted pursuant to Rule 506. 4 Since the effectiveness of Rule 506(c) that eliminated the ban on general solicitation,only a small proportion (4%; 255 billion) of the capital raised in Regulation D offeringswas raised in offerings conducted pursuant to Rule 506(c). Capital raised through Regulation D offerings continues to be positively correlated withpublic market performance, suggesting that capital formation in the unregisteredmarket is pro‐cyclical, i.e., the strength of the unregistered market is closely tied to thehealth of the public market and the overall economy. Consistent with the original intent of Regulation D to target the capital formation needsof small business, the median size of offerings by non‐financial issuers is less than 1million. Approximately 398,000 investors participated in Regulation D offerings during 2017. Alarge majority of these investors participated in offerings by non‐financial issuers. Non‐accredited investors were present in only 9% of Regulation D offerings.3All issuers that are not pooled investment funds (e.g., hedge funds, venture capital funds, and private equityfunds) and that are not in the following Form D listed industries: commercial banking, insurance, investing,investment banking, and other banking & financial services. This group is primarily comprised of operating firms.4Regulation D was amended in October 2016 to, among other things, increase the dollar amount offeringthreshold in Rule 504 from 1 million annually to 5 million annually and to eliminate Rule 505. See SEC Rel. No.33‐10238 (Oct. 26, 2016), available at: f. The amendments toRule 504 became effective on January 20, 2017, while the elimination of Rule 505 became effective on May 22,2017.2

I. IntroductionSecurities laws require that all offers and sales of securities be either registered with theSecurities and Exchange Commission (SEC) under the Securities Act of 1933 or made in relianceupon an exemption from registration. When raising capital through the sale of securities to anypotential investors in the public capital market (a “public” offering), the issuer must generallyregister the offer and sale of securities with the SEC, a process that is accompanied by extensiveinformation production and subsequent reporting, unless an exemption from registration isavailable.5 Alternatively, a company can raise capital by accessing the private capital marketsthrough an unregistered (“private”) offering in a transaction exempt from registration. Ingeneral, this path reduces an issuer’s regulatory obligations, as compared to the obligationsattendant to registered public offerings, thereby reducing issuance costs and the time requiredto raise new capital. This particularly benefits smaller firms, for whom accessing public capitalmarkets may generally be too costly. However, because of these accommodations, privateoffering alternatives are generally subject to investor restrictions and/or offering limits. Theseinvestor protection provisions must be met to qualify for an exemption from registration.The private offering market is governed by several exemptions from registration,including those under Sections 4(a)(2), 3(b) and 3(a)(11) of the Securities Act. For example,Section 3(b) is the exemptive authority for Rule 504 under Regulation D, as well as Regulation Athat was amended, effective June 2015, pursuant to Title IV of the JOBS Act.6 Other parts of theprivate market rely on "safe harbors": rules and regulations that set forth specific conditionsthat, if satisfied, ensure compliance with an exemption from registration. For example, issuerscan use non‐exclusive safe harbors such as Rule 506(b) of Regulation D, which is a safe harborunder Section 4(a)(2), Regulation S for offerings outside of the U.S., and Rule 144A for theresale of restricted securities to qualified institutional buyers (QIBs). A comparative analysis ofthe characteristics of these and other offering exemptions and safe harbors is provided inAppendix II. The Commission also recently adopted final rules that increased the maximumoffer size under Rule 504 from 1 million to 5 million and repealed Rule 505 in light of itslimited and declining usage.7 These changes to Regulation D (amended Rule 504 and repeal ofRule 505) became effective in 2017.The importance of private capital markets as a source of financing in the economy isunderscored by the fact that less than 0.02% of the estimated 5.8 million employee‐based firms5For example, an exception to the general rule exist in unregistered securities offerings conducted pursuant toRegulation A, an exemption from registration for securities offerings of up to 50 million annually.6Among the changes in Regulation A is an increase in the amount of capital that can be raised (from 5 million to 50 million) and state securities law preemption for certain offerings.7Exemptions to Facilitate Intrastate and Regional Securities Offerings, Release No. 33‐10238 (October 26, 2016).3

and 23.8 million non‐employer firms in the U.S. are currently exchange listed firms.8 Moreover,there has been a steady and significant decrease in the number of public reporting companiesin the U.S., particularly since the dot com crash and implementation of the Sarbanes‐Oxley Act.9During this period, private offerings of securities have contributed significantly to capitalformation in the U.S. economy, particularly for small and emerging companies that are oftenconsidered to be the engine for creating new jobs,10 driving innovation, and for acceleratingeconomic growth. Hence, private capital markets provide an important financing alternative forcompanies that for various reasons forego financing in the public capital markets.This study focuses on securities issuances by issuers that conduct unregistered offeringspursuant to Regulation D of the Securities Act. Currently, Regulation D is comprised of threerules: Rule 504, Rule 506(b) and Rule 506(c). 11 The analysis updates and extends previous workby SEC staff on this topic,12 and includes a comprehensive look at the use and effect of theintroduction of Rule 506(c) under Title II of the JOBS Act, which allows an issuer to generallysolicit investors and generally advertise its offering. A critical component of our analysis is thedata we rely on. The data used in the study, including how we compiled our sample, isdescribed in detail in Appendix I. As the analysis below shows, Regulation D remains a widelyused regulation for conducting unregistered offerings of securities. More than 1.8 trillion wasreported as sold during 2017, the highest levels reported since Form D filings became machinereadable in 2008.13 This amount is larger than the amount of capital raised by public equity anddebt offerings combined. And as indicated in the next Section, it is likely that the reported dataon Regulation D offerings underestimates the actual amount raised through offerings wherethe issuer intended to rely on Regulation D. Most of the 1.8 trillion was reported raisedthrough Rule 506(b), which prohibits general solicitation and general advertising, and limitsinvestor participation to accredited investors and up to 35 sophisticated non‐accredited14,8Data is for 2014. See B‐FAQ‐2017‐WEB.pdf. Also see,There were 4,369 listed domestic companies in 2014. See, World Federation of Exchanges Database, World OM.NO?locations US.9See Doidge, C., A. Karolyi, and R. Stulz, The U.S. Listing Gap, The Journal of Financial Economics, Vol 123, Issue 3,March 2017.10The United States Small Business Administration estimates show that small businesses accounted for 48% of U.S.employment during 2014, and contributed to creating 62% of all net new jobs during 1993‐2016.See B‐FAQ‐2017‐WEB.pdf.11See fn. 4 above.12See, the 2015 Unregistered Offerings Study.13Prior to 2008, filings were filed in paper making large scale extraction from tens of thousands of filingsimpractical.14These are investors that do not meet the definition of an accredited investor provided under Rule 501 ofRegulation D. Generally, accredited investors are institutions that have total assets of at‐least 5 million or naturalpersons that have individual income of at least 200,000, joint income of at least 300,000, in each of the last twoyears and an expectation to reach the same income in the current year, or net‐worth (excluding primary residence)of at‐least 1 million. See Section IVb. for more information on investors in Regulation D offerings.4

investors. Amounts reported raised under Rule 506(c) remain a small fraction of the total (4%)of the capital reported raised pursuant to Regulation D since the rule became effective onSeptember 23, 2013, suggesting that most issuers of unregistered securities are not yet seekinginvestors through general solicitation and general advertising.Among the other findings, the majority of the capital raised in the Regulation D marketin 2017 was raised by pooled investment vehicles ( 1,671 billion), while non‐financial issuersraised 105 billion.15 Regulation D offerings are very popular with small businesses: there havebeen more than 100,700 issuances by non‐financial issuers since 2009, with a median offer sizeof less than 1 million. Unlike public offerings, only 20% of new Regulation D offerings since2009 report using a financial intermediary. The average commission is 6%, but it variessignificantly by the size of the offering and the type of the issuer involved.The results of our analysis take into consideration several factors that may affect anissuer’s choice of offering method for issuance of unregistered securities, such as preemptionof state securities laws, ability to advertise, ability of non‐accredited investors to participate,limits to the amount of capital that can be raised, geographical constraints, and level ofrequired initial and ongoing disclosure to investors. These factors may affect both the level ofburden (costs) incurred by an issuer to raise capital as well as the amount of protectionavailable to investors, including, for instance, through additional oversight by state securitiesregulators.Similarly, while Regulation D has been in existence since 1982, other private offeringissuance methods are newer, such as those arising from the JOBS Act (e.g., the new Rule 506(c)effective since September 2013, the amended Regulation A effective since June 2015, theRegulation Crowdfunding since May 2016 and the amended Rule 147 and new Rule 147A forintrastate offerings that became effective April 2017). The last section in this study presents acomparative analysis of capital raising activity under Regulation D exemptions relative toRegulation A and Regulation Crowdfunding. Compared to Regulation A and RegulationCrowdfunding offerings, Regulation D offerings of similar offering sizes are much morenumerous and raise significantly more capital. Additionally, very few Regulation Crowdfundingissuers have used the Regulation D market in the past, suggesting that RegulationCrowdfunding, at least based on data as of December 31, 2017, tends to bring new issuers tothe private offering market rather than encouraging current issuers to switch between privateofferings exemptions. A caveat is due, however, since we do not observe if these RegulationCrowdfunding issuers use other private offering exemptions for which we do not have data15Pooled investment vehicles include hedge funds, private equity funds, venture capital funds, commodity pools,and a few other types of funds. In the paper we use the terms “pooled investment vehicles” and “funds”interchangeably. Non‐financial issuers are defined as operating companies that are outside of the financial sector.5

(e.g., Section 4(a)(2) offerings). As of December 31, 2017, approximately 61% of Regulation Aissuers have undertaken private offerings16, most of them in reliance on Section 4(a)(2) orRegulation D, suggesting that, at least based on the two and a half years of data since thechanges in Regulation A became effective, most issuers in this market tend to switch betweenprivate offerings exemptions. Additionally, we do not have enough information to determinethe extent to which some of these newer rules and the amendments to Regulation D thatbecame effective in 2017 (amended Rule 504 and repeal of Rule 505) will affect the importanceof Rule 506(b) and 506(c) of Regulation D or serve as alternatives to registered offerings.The study is organized as follows. Section II provides an overview of the private offeringsmarket. Section III provides an overview of capital formation in the market for Regulation Dofferings. Section IV provides a detailed analysis of the characteristics of market participants inthe Regulation D market. Section V compares Regulation D offerings and issuer characteristicsto similar Regulation A and Regulation Crowdfunding offerings.16See Anzhela Knyazeva, Regulation A : What do we know so far? (November 2016), available athttps://www.sec.gov/files/Knyazeva RegulationA%20.pdf6

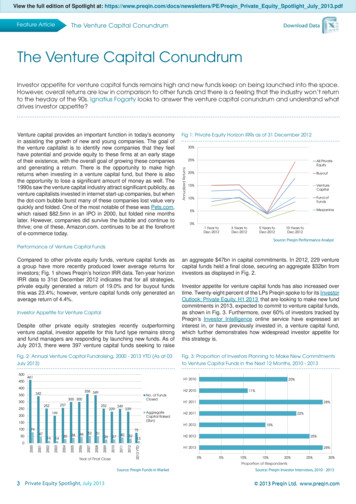

II. The size of the private offerings marketTo estimate the total size of the private offerings market, we sum the total amount ofsecurities sold using available data17 for each of the main private offering exemptions duringthe period 2009‐2017, including: Regulation DRule 144A (resale of unregistered securities to QIBs)Regulation S (offshore component of 144A offerings)Regulation A offeringsRegulation Crowdfunding offeringsOther Section 4(a)(2) private offeringsData for some of these exemptions is more readily available than for others. For example,because issuers relying on Section 4(a)(2) are not required to file any document with theCommission, offering information available in the commercial databases likely underestimatesthe amount of capital raised through this exemption. Similarly, the available data on RegulationD offerings could underestimate the true amount of capital raised through such offerings. WhileRule 503 of Regulation D requires the filing of a notice on Form D no later than 15 days afterthe first sale of securities, the filing of a Form D is not a condition to claiming a Regulation Dsafe harbor or exemption, and it is possible that some issuers do not file Forms D for offeringsrelying on Regulation D.18Figure 1 illustrates that the total capital raised annually in the private capital market islarge both in absolute terms and when compared to the amounts raised in the public markets.In 2017, registered offerings accounted for 1.5 trillion of new capital compared to more than 3.0 trillion reported raised through all private offering channels. The amount raised by17Data on Regulation D offerings was collected from all Form D filings (new filings and amendments) on EDGARfrom January 2009 through December 2017; Data on non‐ABS Rule 144A offerings was collected from ThomsonFinancial SDC new Issues database, Dealogic, and the Mergent database. Data on ABS and CMBS Rule 144Aofferings was collected from the Asset‐Backed Alert and Commercial Mortgage Alert publications; Data forRegulation S offerings was collected from Thomson Financial’s SDC Platinum service; Data on Regulation A andRegulation Crowdfunding offerings was collected from all Form 1‐A and Form C filings (new filings andamendments) on EDGAR from May 2015 through December 2017; and Data for other private offerings (excludingRegulation A and Regulation Crowdfunding offerings) was collected from Thomson Financial’s SDC Platinum, whichuses information from underwriters, issuer websites, and issuer SEC filings to compile its Private Issues database.These include offerings under Section 4(a)(2) of the Securities Act that do not claim a Regulation D or Reg Sexemption and that are without a follow‐on Rule 144A sale. These numbers are accurate only to the extent thatSDC is able to collect such information, and may understate the actual amount of capital raised under Section4(a)(2) if issuers and underwriters do not make this data available.18Separate analysis by DERA staff of Form D filings by funds advised by registered investment advisers and broker‐dealer members of FINRA suggests that Form D filings are not made for as much as 10% of unregistered offeringseligible for relief under Regulation D.7

Regulation D offerings, 1.8 trillion, is considerably larger than the amount of public debt(straight and convertible debt) and public equity (common and preferred) offerings over thesame time.19 Rule 144A offerings are predominantly debt offerings while Regulation D offeringsare mainly equity offerings, although a non‐trivial number of the latter include debt securitiesbut the amounts are not separately reported. Within the private capital market, Regulation Dand Rule 144A are the dominant offering methods. Over the period 2009‐2017, the amount ofcapital raised through Regulation D offerings is much larger than, the amount of capital raisedunder Rule 144A.20Figure 1. Aggregate capital raised in 2009‐2017 by offering method ( billions)Registered debtRegistered equityReg DRule 144AOther ,8002,000Amount Raised ( billion)2017201620152014201320122011* Other private includes Regulation S offerings, Section 4(a)(2) offerings, Regulation Crowdfunding offerings, andRegulation A offerings.19Data for registered debt and equity offerings from Thomson Financial’s SDC Platinum.By its terms, Rule 144A is available solely for resale transactions. However, market participants use it tofacilitate capital‐raising by issuers by means of a two‐step process, in which the first step is a primary offering onan exempt basis to one or more financial intermediaries, and the second step is a resale to “qualified institutionalbuyers” in reliance on Rule 144A.208

Table 1 estimates the size of the private and public markets in terms of number ofofferings per year. As the table shows, offerings in the private market occur with a significantlyhigher frequency compared to public market issuances. Regulation D offerings occur with fargreater frequency than any other offering method surveyed, indicating that the accumulationof capital raised through Regulation D occurs by way of much smaller offering denominationsthan other methods. This finding is consistent with Regulation D being the primary tool forcapital raising by smaller entities. In contrast, Rule 144A offerings are larger in dollar terms,reflecting its use by larger issuers. The large increase in ‘Other private offerings’ in 2017compared to previous years comes mainly from Regulation Crowdfunding and Regulation Aofferings.Table 1. Number of offerings by type of offering and yearPublic OfferingsPrivate OfferingsYearPublic equityPublic debtRegulation DRule 144AOther *Includes offerings conducted under Regulation S, qualified Regulation A, Regulation Crowdfunding, and Section4(a)(2).III. The Regulation D marketRegulation D was promulgated in 1982 to provide a unified scheme for exempting certaincapital offerings from registration requirements. It was designed to simplify existing rules andregulations to facilitate capital formation, particularly for small businesses, consistent with theprotection of investors. At its inception, the Regulation D market was comprised of three rules:Rule 504, Rule 505, and Rule 506.Rule 506 was amended pursuant to Title II of the JOBS Act, which directed theCommission to permit general solicitation and general advertising in Rule 506 offerings.21 Rule506(c) became effective on September 23, 2013 and allows for general solicitation and21Pub. L. No. 112‐106, § 201(a), 126 Stat. 306, 313 (Apr. 5, 2012).9

advertising in Rule 506 offerings as long as all purchasers are accredited investors and issuerstake reasonable steps to verify that such purchasers are accredited investors.22 Rule 506, as itexisted before the adoption of Rule 506(c), was preserved and re‐designated as Rule 506(b).As noted above, in view of the low levels of usage of Rule 505, SEC recently repealed theRule 505 exemption, effective May 22, 2017.23 At the same time, the Commission amendedRule 504 to increase the aggregate amount of securities that may be offered and sold in a 12‐month period, from 1 million to 5 million.24 In addition to being more reflective ofcontemporary seed‐capital needs of early stage companies, the higher ceiling under Rule 504was adopted to facilitate the development of regional offerings, and intrastate crowdfundingofferings.The tables and figures in this section provide a broad overview of capital formation inthe Regulation D capital market and its various exemptions. The information in this section, aswell as the following Section IV, that provides a detailed analysis of the characteristics ofRegulation D market participants is based on information reported in Forms D and D/A filed byissuers of such offerings.a. Capital raised in Regulation D marketAnalysis of issuer self‐reported data through electronic Form D filings in Table 2 revealsthat the number of unregistered offerings and corresponding amounts raised have beenincreasing over the years 2009‐2017.25Table 2. Capital raised through Regulation D and Regulation D/A (amended) offerings*Regulation D Regulation D/ATotalMeanMedianfilingsfilingsamount soldamount soldamount sold*Year(number)(number)( Billions)( millions)( 332241.5201522,85315,6491,361251.522Eliminating the Prohibition Against General Solicitation and General Advertising in Rule 506 and Rule 144AOfferings, Release No. 33‐9415 (July 10, 2013) (“Rule 506(c) Adopting Release”). General solicitation had not beenallowed for Rule 506 offerings since its enactment in 1982 as a non‐exclusive safe harbor under Section 4(a)(2) ofthe Securities Act of 1933.23See fn. 7 above.24Id., The new provisions of Rule 504 became effective in January 20, 2017.10

*Mean and median amount sold based on initial (new) Form D filings only. Total amount sold includes additionalamounts raised and reported in amended filings, recorded at the time of the amendment.These estimates are based on the reported “total amount sold” at the time of the originalfiling – required within 15 days of the first sale – as well as any additional capital raised andreported in amended filings. The data likely underreport the actual amount sold due to twofactors. First, because electronic filings were phased‐in through the end of March 2009, paperfilings in the first quarter of 2009 are not captured in the analysis. Underreporting could occurin all years because Regulation D filings can be made prior to the completion of the offering,and amendments to reflect additional amounts sold generally are not required if the offering iscompleted within one year and the amount sold does not exceed the original offering size bymore than 10%. Second, as previously described, Rule 503 requires the filing of a notice onForm D, but filing a Form D is not a condition to claiming a Regulation D safe harbor orexemption. Hence, it is possible that some issuers do not file a Form D for offerings relying onRegulation D.26 Finally, in their annual amendments, some funds appear to report net assetvalues for total amount sold under the offering. Net asset values could reflect fundperformance as well as new investment into, and redemptions from, the fund. Based on Form Ddata, it is not possible to distinguish between the two impacts.b. CyclicalityIt is a well‐documented empirical fact that public capital markets are cyclical and thecyclicality appears to be driven by the business cycle, investor sentiment, and time‐varyinginformation asymmetry.27 However, there is little empirical evidence on the cyclicality of capitalraised through private offering markets, and in particular, whether issuers rely more on privatemarkets when public markets are under distress (e.g., during recessions).Figure 2 shows Regulation D offering activity based on the number of offerings bycalendar year, relative to the S&P 500 index, for the period 1993‐2017. These numberscorrespond to all new (non‐amended) Form D filings on the EDGAR filing system. While the datadoes not indicate the aggregate amount raised through these offerings, Table 2 shows that26Separate analysis by DERA staff of Form D filings by funds advised by registered investment advisers and broker‐dealer members of FINRA during the period 2009‐2011 suggests that Form D filings are not made for as much as10% of unregistered offerings eligible for relief under Regulation D.27See Ivanov, I. and C. Lewis, The Determinants of Market‐Wide Issue Cycles for Initial Public Offerings, Journal ofCorporate Finance, December 2008; Lowry, M., Why Does IPO Volume Fluctuate So Much?, Journal of FinancialEconomics, January 2003; and Choe,H. , R. Masulis and V. Nanda: Common Stock Offerings Across the BusinessCycle: Theory and Evidence, Journal of Empirical Finance, June 1993.11

offering sizes, on average, are fairly constant over the most recent five years, suggesting thatthe year‐to‐year changes in the number of offerings may also track changes in the 01,50010,0001,0005,000S&P 500 IndexNumber o f OfferingsFigure 2. Number of Regulation D offerings: 1993‐201750001993199

19, 2015 and the new Regulation Crowdfunding that became effective May 16, 2016. We also provide some perspective on the state of competition and potential regulatory burden in alternate capital markets by analyzing the level of activity among the various registered and unregistered offering alternatives.