Transcription

Instructions for Continuing Nursing Education Contact Hours appear on page 317.Nurses’ Perceptions of Role, TeamPerformance, and EducationRegarding Resuscitation in the AdultMedical-Surgical PatientSharon C. O’Donoghue, Susan DeSanto-Madeya, Natalie Fealy,Christine R. Saba, Stacey Smith, Allison T. McHughardiovascular disease is theleading cause of death in theUnited States (Centers forDisease Control and Prevention[CDC], 2015). While morbidity andmortality from most cardiovasculardiseases have declined over the past30 years, survival rates after cardiopulmonary events have shownlittle change. Approximately 200,000cardiac arrests occur in U.S. hospitalsannually (Merchant et al., 2011).Unfortunately, many affected patients die before discharge. Survivalrates to discharge after in-hospitalcardiac arrest are only 22.3%-28.1%depending on initial rhythm(Girotra et al., 2012). Optimal outcomes for victims of cardiac arrestdepend on the concerted effort of awell-trained, highly efficient team.Formal life support training programs (advanced cardiac life support [ACLS], basic life support [BLS])with nationally accepted guidelinesincorporate cognitive and psychomotor skills to standardize careof victims of cardiac arrest. Teamwork and leadership training canimprove team performance duringresuscitation and have been included in guidelines for ACLS classes(Hunziker et al., 2011). Sodhi,Singla, and Shrivastava (2011) similarly found formal training of clinical staff participating in cardiacresuscitation drastically improvedreturn of spontaneous circulationand rates of survival to hospital discharge for patients who experienced cardiac arrest.CThe purpose of this study was to explore nurses’ perception of theirroles, team performance, and educational needs during resuscitation using an electronic survey. Findings provide direction for clinicalpractice, nursing education, and future research to improve resuscitation care.Team performance depends inpart on identification and delegation of team roles and tasks. A lackof clarity exists within the literatureon code team composition andteam members’ specific roles duringa resuscitation (Lauridsen, Schmits,Adelborg, & Lefgren, 2015). Roleambiguity and confusion for codeteam members often exists, possiblycreating poor communication andineffective teamwork that lead topoor patient outcomes. A first stepin optimizing team performance isunderstanding the prevalence andnature of role ambiguity amongmembers of the code team.BackgroundPerception of RolesThe size, composition, and rolesof each code team are highly variable. Roles may not be definedclearly during formal training. Forexample, while the role of teamleader is discussed in the 2011 ACLSProvider Manual (Sinz, Navarro,Soderberg, & Callaway, 2011), rolesof other team members in cardiacresuscitation are not. Membersoften are identified simply asresponders and may not understand who is responsible for eachSharon C. O’Donoghue, MS, RN, CNS, is Clinical Nurse Specialist, Beth Israel DeaconessMedical Center, Boston, MA.Susan DeSanto-Madeya, PhD, RN, CNS, is Associate Professor, Connell School of Nursing,Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA; and Nurse Scientist, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center,Boston, MA.Natalie Fealy, MSN, RN, CCRN, CCNS, is Legal Nurse Consultant, DeLuca & Wiezenbaum,LLC, Providence, RI.Christine R. Saba, APRN-BC, ACNS-BC, is Adult Nurse Practitioner-Internal Medicine, SouthShore Medical Center, Norwell, MA.Stacey Smith, MA, BSN, RN, CCRN, is Unit-Based Educator, Cardiac Care Unit, Beth IsraelDeaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA.Allison T. McHugh, MS, BSN, RN, MHCDS, NE-BC, is Administrative Director of NursingMedicine, Cardiac, and Neurosciences, Dartmouth Hitchcock Medical Center, Lebanon, NH.Acknowledgment: The authors thank Kathy M. Baker, MSN, RN, and Susan Craft, MS, RN,for their assistance with this study.September-October 2015 Vol. 24/No. 5309

delegated role within the team(Capella et al., 2010).Nurses with varying experienceand training may be members ofthe code team. For instance, thecode team may include critical carenurses who hold critical care certification and/or are ACLS-preparedand medical-surgical nurses withBLS and/or ACLS preparation. Theirtraining and experience will influence the roles they perform as wellas their ability to conceptualizetheir roles. Experienced nurses maybe comfortable in a variety of rolesin any emergency, including serving as the team leader until a moresenior ACLS provider arrives. Theroles of less-experienced nurses maybe more limited and less clear(Capella et al., 2010).The roles a medical-surgicalnurse performs during resuscitationdepend on different variables, suchas knowledge and skill level (Porter,Cooper, & Taylor, 2014). Medicalsurgical nurses are often first responders to a resuscitation and subsequently initiate BLS while waitingfor the code team to arrive. Duringresuscitation, medical-surgical nurses may be required to perform multiple tasks, including compression,airway management, defibrillation,medication administration, codecart management, and documentation (Jackson & Grugan, 2015).Various opinions on medical-surgical nurses’ role on a code team arefound in the literature. Heng, Fong,Wee, and Anantharaman (2011)suggested medical-surgical nursesshould not participate in defibrillation, while Jackson and Grugan(2015) indicated defibrillation is aprimary role for medical-surgicalnurses. While the role of the medical-surgical nurse may vary, itshould be guided by a nurse’s specific competence.The nurse assigned to managethe code cart must have a workingknowledge of its contents and knowhow to utilize all supplies. Nursesadministering medications duringresuscitation need to be familiarwith the drugs and doses. Nursesperforming chest compressions andbag-valve mask ventilation shouldbe familiar with the most current310evidence-based procedures, andshould have met basic competencies relative to this role. The eventrecorder should be familiar with allaspects of documentation neededfor the care provided (Jackson &Grugan, 2015). In addition, Dorney(2011) described a go-to role designed to provide additional support, such as crowd control, familysupport, additional equipment, andgeneral expertise.Optimal team performance notonly requires all members to becomfortable with their own roles,but also to understand the roles ofthe other team members. Understanding these roles and havingconfidence in each one enables eachmember to contribute to the team’soverall performance (Marshall &Flanagan, 2010).Team Performance,Communication, andTeamwork in ResuscitationA high-performing team canexceed expectations in manyinstances, especially when all members of the team are aware of thegoal and how best to achieve it.Team performance can be strainedin a resuscitation because of itsurgency, with multiple demandsplaced on responding team members. To have an effective team,roles of each team member must bedefined and understood by members (Hunziker et al., 2011). When acode has been called, team members generally come from differentareas of the hospital to provide careto a critically ill patient and maynot be accustomed to workingtogether (Jackson & Grugan, 2015).Effective team performance and collaboration are essential duringresuscitation. In addition, optimalperformance requires a strong teamleader. A major responsibility of theleader involves delegating and clarifying team member roles to optimize team performance (Hunzikeret al., 2011). Using simulated cardiac arrests, Marsch and colleagues(2005) found lack of clear leadership behaviors combined with theabsence of task assignment wereassociated with poor team perform-ance. Ineffective team leadershipthus may contribute to role ambiguity and ineffective team dynamics. Authors indicated performanceof cardiac arrest teams has beenenhanced significantly by efforts todevelop teamwork and communication. Understanding this relationship is fundamental to designinginterventions to optimize team performance.Debriefing, or bringing the grouptogether to assess the conduct andresults of an event systematicallyand objectively, may improve performance in future events. Edelsonand colleagues (2008) suggestedweekly debriefing may improveobjective measurements of resuscitation quality and initial patientoutcomes from in-hospital cardiacarrests. Dine and co-authors (2008)measured depth of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) compressions to demonstrate how debriefing alone can improve CPR performance.To improve patient outcomesand enhance safety, cardiac arrestteams should include highly skillednurses who demonstrate excellentcommunication and teamworkbehaviors. In the landmark safetyreport To Err is Human: Building aSafer Health System (Kohn, Corrigan,& Donaldson, 2000), communication and language problems weresuggested as a root cause of accidentsin health care. Differences in communication style between nursesand physicians also contribute tocommunication errors. Communication problems may be explainedby a lack of shared understandingamong team members about theirrespective roles, tasks, and objectives (Westli, Johnsen, Eid, Rasten,& Brattebo, 2010).Literature ReviewA review of the research literature was conducted using electronicdatabases CINAHL and MEDLINE.Databases were searched using acombination of search terms: nurse,nursing, roles, codes, code blue, resuscitation, teamwork, CPR, ACLS, BLS,education, and survey. Results werelimited to English-language reportsSeptember-October 2015 Vol. 24/No. 5

Nurses’ Perceptions of Role, Team Performance, and Education RegardingResuscitation in the Adult Medical-Surgical Patientof empirical studies publishedJanuary 2008-May 2015. Researchfocused specifically on roles, teamperformance, and education inresuscitation was not found in theliterature; however, team trainingand performance, BLS and ACLScertification, mock codes, anddebriefing to improve resuscitationoutcomes were addressed in a number of research articles.Westli and colleagues (2010)questioned if training in teamwork,team skills, and behaviors wouldimprove trauma team performanceduring simulations. Clinicians in 27trauma teams (N 139) were educated on team training and participated in a simulation exercise. Individual teamwork and overallteamwork behaviors were observedand summarized along with theteam’s medical management of thecase-based scenario. A revised version of the Anaesthetists’ NonTechnical Skills behavioral markersystem, the Anti-Air TeamworkObservation Measure, and teamobservations were used to assesstheir team performance during thesimulation. Data were analyzedusing multiple regression analyses,correlation analysis, and t-tests.Findings indicated improving teamwork skills led to a shared mentalmodel and thus improved team performance.Capella and colleagues (2010) investigated the impact of simulatedteam training on behaviors, efficiency, and clinical outcomes. Thispre-post interventional study occurred at a level 1 trauma centerwhere faculty, nurses, and surgicalresidents participated. Pre-data werecollected and simulated team training was conducted over a 3-monthperiod. Team performance wasmeasured using the Trauma TeamPerformance Observation Tool.Clinical parameters (time fromarrival to computed tomographyscanner, arrival to intubation,arrival to operating room, arrival toFocused Assessment Sonography inTrauma examination, time in emergency department, hospital lengthof stay [LOS], intensive care unitLOS, complications, and mortality)were identified as ways to measureefficiency. Teamwork ratings, clinical parameters, and significancewere determined using the independent samples t-test. Simulatedteam training significantly improved overall team performance(p 0.001).In a randomized interventionalstudy, Dine and colleagues (2008)investigated the impact of debriefing versus real-time audiovisualfeedback on performance duringresuscitation. Eighty nurses wererandomized into two groups andparticipated in three simulatedresuscitations at an academic medical center. One group receiveddebriefing only and the other groupreceived real-time audiovisual feedback in addition to debriefing following the simulations. Groupmembers who received debriefingonly improved their compressionperformance from 38% to 68%(p 0.015). In the feedback group,compression depth improved from19% to 58% (p 0.002). The combination of both feedback anddebriefing improved the compression rate from 45% to 84%(p 0.001). Findings indicated bothdebriefing and feedback are necessary to improve cardiopulmonaryresuscitation.In a prospective study, Marschand colleagues (2005) assessed ifnurses as first responders to resuscitation followed the algorithm and ifphysician presence altered the performance of the nursing team.Personnel from a tertiary intensivecare unit participated in a cardiacarrest simulation. Eighty participants were divided into teams consisting of three nurses and one resident. The recognition of arrest toinitiation of resuscitation occurredin a median of 85 seconds and timeto first defibrillation was a medianof 100 seconds. The early availability of a resident increased the number of counter shocks delivered from4.5 versus 3.5 (p 0.26). Overall,recognition of arrest by nursesoccurred in a timely manner; thedelayed presence of a resident led toa decrease in team performance.Price, Applegrath, Vu, and Price(2012) developed a survey to identify areas for improvement in resusci-September-October 2015 Vol. 24/No. 5tation responses. Forty-nine nursesand 19 anesthesiologists from theoperating room and postoperativerecovery unit in a Canadian hospital completed a survey of 25 multiple-choice and 6 open-ended questions regarding their resuscitationexperiences. Respondents identifiedfour areas to improve patient outcomes: team training, debriefing,identification of the team leader,and limiting the number of responders in the room. Respondents fromboth disciplines indicated havingtoo many responders in resuscitations hindered team performanceand regular debriefing sessionswould improve outcomes.Education increased team performance and patient outcomes inadditional studies. Andreatta, Saxton,Thompson, and Annich (2011) evaluated the effectiveness of code simulation training at a pediatric academic medical center over a 48month period. All events wererecorded during the simulation andreal-time feedback was given toindividual residents regarding theirperformance. Following initiationof the code simulation, self-assessment data were collected from allteam members and pediatric resuscitation survival rates were examined. Qualitative analysis revealedsimulation training increased residents’ confidence and leadershipabilities during multiple mockcodes throughout their 3-year residencies. Mock codes also improvedpediatric patient survival rates from33% after the introduction of 10mock codes to 50% within a year ofintegrating mock codes into the residency curriculum (p 0.000). Improvements were sustained for 3years following study completion.Sodhi and colleagues (2011) conducted an one-site retrospectivestudy using a pre-post design toevaluate the effects of BLS and ACLScourses on CPR outcomes. Duringthe study period, 627 in-hospitalcardiac arrests occurred (284 pretraining, 343 post-training). Fiftytwo patients (18.3%) had return ofspontaneous circulation in the preBLS/ACLS training, compared to 97patients (28.3%) in the post-BLS/ACLS training (p 0.005). Return of311

spontaneous circulation and survival to hospital discharge were significantly higher in the post-training group (67 patients, 69.1% vs. 12patients, 23.1%; p 0.0001). BLS andACLS preparation improved survivalrates after in-hospital cardiac arrests.In a pre-post study, Edelson andassociates (2008) used an educational intervention (resuscitationwith actual performance integrateddebriefing [RAPID]), to evaluateCPR performance and return ofspontaneous circulation. Over 11months, internal medicine residents attended a weekly meeting fordebriefing of all resuscitations inthe previous week. CPR transcriptsfrom feedback-enabled defibrillators and real-time audiovisual feedback from the resuscitation werereviewed during the debriefing sessions. Data from 123 patients resuscitated during the interventionperiod were compared to 101patients from historical (pre-intervention) data. CPR quality andreturn of spontaneous circulationimproved following the intervention (59.4% vs. 44.6%; p 0.03) butno improvement occurred in survival rates. The combination ofRAPID and debriefing was associated with improvements in the returnof spontaneous circulation secondary to improved delivery of CPR.Code team composition is highlyvariable and poorly defined in theliterature. Lauridsen and colleagues(2015) evaluated the compositionof in-hospital resuscitation teamsfrom 54 Danish hospitals using across-sectional design. Resuscitationteam composition was obtainedfrom each hospital’s resuscitationprotocol and interviews. Some hospitals did not identify the teamleader or the responsibilities of teammembers. Identified team memberswere leader, chest compressor,defibrillation, airway handler, andmedication administrator.Porter and co-authors (2014) alsoinvestigated the composition ofteam members and the role of afamily liaison in resuscitation. Froma sample of 282 nurses and 65 doctors in 18 public emergency departments in Australia, seven roles wereidentified: team leader, airway doc312tor and nurse, procedural doctorand nurse, scribe, and drug nurse.Although similar team members’roles were identified in both thesestudies, staff perceptions of theseroles were not explored. Despitethese findings, a paucity of researchexists examining staff nurses’ perceptions of roles, team performance, and education regardingresuscitation.PurposeIncreasing team members’ understanding of others roles acrossdifferent specialties could improveteamwork during a code. The purpose of this study was to explorenurses’ perception of their roles,team performance, and educationalneeds during resuscitation.MethodsBecause an instrument assessingclinical nurses’ perceptions of theirroles and performance regardingresuscitation was not found in theliterature, four clinical experts atthe study site created a four-pagepaper survey based on personalexperiences and findings from theliterature. The survey then wasdistributed to a group of multidisciplinary experts from the codecommittee, including representatives of nursing, medicine, criticalcare, anesthesia, pharmacy, andrespiratory care. Comments andinput for improvement were considered and the survey was revised.The final survey was converted toan electronic format for distributionto staff. Average time for surveycompletion was 10-15 minutes.The original survey consisted ofseven sections; the following sixsections will be discussed in thisarticle: demographics, code experience,perception of team, role assignment,perception of comfort, and codeeducation. Demographic questionsincluded the participant’s healthcare discipline, years of experience,number of experiences with codes,code training received, and yearsworked at this institution. The codeexperience section included questions about the perception ofleadership, debriefing, communication, and roles during a code. Theperception of team section includedspecific questions regarding teamperformance related to leadership,debriefing, and communicationskills among code team membersduring an adult resuscitation. Therole assignment section includedquestions about perceptions ofindividual roles and roles of otherteam members during a resuscitation. The perception of comfortsection addressed respondents’overall comfort and/or confidencein resuscitation. The final section,code education, asked specificquestions about the type andhelpfulness of education received,and what learning opportunitieswould be beneficial in improvingskills during ore study implementation,approval was obtained from thestudy site’s Institutional ReviewBoard. The study site was an acutecare level 1 trauma center. Aconvenience sample was obtainedby sending an email to all clinicalnurses who had participated in orhad the possibility to participate inadult resuscitation on a medicalsurgical unit. All respondents wereasked to complete the survey basedon their experiences in adultresuscitation outside the intensivecare unit while serving as membersof the code team. Clinical staff fromthe neonatal intensive care unit,emergency department, operatingroom, or post-anesthesia care unitwere excluded because they do notparticipate in resuscitation onmedical-surgical units.An email explaining the studywas sent to all clinical staff who metthe inclusion criteria. Each specificdiscipline identified a designatedchampion who sent the email andsurvey link to staff on behalf of theresearch team. Potential participants were assured anonymity andconfidentiality. Completion of thesurvey served as their voluntaryconsent.September-October 2015 Vol. 24/No. 5

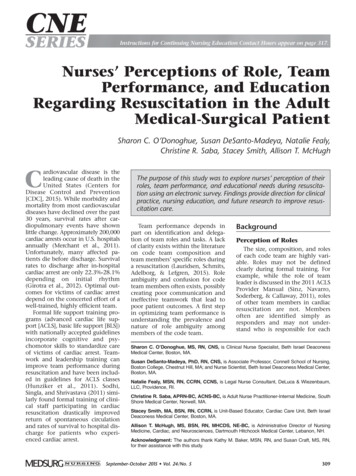

Nurses’ Perceptions of Role, Team Performance, and Education RegardingResuscitation in the Adult Medical-Surgical PatientTABLE 1.Sample Demographics (N 239)Medical-Surgical NursesNumber/Percentage(n 184)Critical Care NursesNumber/Percentage(n t comfortable/Confident71(39%)6(10%)Not very comfortable/Confident25(14%)4(7%)Not at all comfortable/Confident7(4%)1(2%)SexMaleFemaleAge60 Previous Participation in ResuscitationParticipation in resuscitationParticipation in 15 resuscitationsComfort/Confidence Level in Performing ResuscitationVery comfortable/ConfidentData AnalysisData were entered into theStatistical Package for the SocialSciences (SPSS) version 19 (IBM;Armonk, NY). Descriptive statisticswere used to analyze demographicand other participant data from thesurvey. Only data obtained frommedical-surgical or critical carenurses were analyzed.Of 239 participants, 184 weremedical-surgical (MS) and 55 werecritical care (CC) nurses. The majority of the medical-surgical nurseswere over age 40 (n 110, 60%). Agerange for the majority of criticalcare nurses was 30 to 59 (n 45,82%). See Table 1 for remainingdemographic data.ResultsPerception of RolesA majority of nurses indicatedtheir roles were defined clearly dur-ing resuscitation (MS n 84, 50%; CCn 29, 55%). Most nurses reportedself-assigning their roles (MS n 134,80%; CC n 52, 96%) during resuscitation, but they perceived roles ofother team members as beingdefined clearly only sometimes (MSn 48, 28%; CC n 27, 52%) to occasionally (MS n 57, 34%; CC n 17,33%). See Table 2 for additionalinformation about role perception.Team Performance,Communication, andTeamwork in ResuscitationBoth medical-surgical and criticalcare nurses reported positive communication and teamwork amongcode team members. Nurses indicated their belief team membersdemonstrated effective skills incommunication (MS n 97, 60%;CC n 27, 51%) and teamwork (MSn 103, 62%; CC n 30, 58%) alwaysor often during a resuscitation.Nurses experienced team membersasking each other for help (MSSeptember-October 2015 Vol. 24/No. 5n 171, 93%; CC n 47, 86%), andcommunicating respectfully (MSn 150, 82%; CC n 44, 80%) withappropriate tone of voice (MSn 150, 82%; CC n 44, 80%). Morethan 80% (n 215) of nurses perceived resuscitation team leaders tobe receptive to new ideas (MSn 169, 92%; CC n 46, 84%) and toassist the code team by verbalizing anew treatment plan (MS n 171,93%; CC n 40, 73%). Less thanone-third of all respondents hadparticipated in one post-resuscitation debriefing (MS n 58, 32%; CCn 15, 27%; see Table 3).Educational ExperiencesAt the time of the study, over96% (n 234) of all responders heldBLS certificates (MS n 181, 98%; CCn 53, 96%). ACLS certificates wereheld by 62% (n 114) of medicalsurgical nurses and 98% (n 54) ofcritical care nurses. Two-thirds ofrespondents indicated a belief unitbased mock codes (MS n 142, 77%;313

TABLE 2.Perception of RolesMedical-Surgical NursesNumber/PercentagenRoles (N 239)nn 184%n 55Record events171(93%)9Support family/significant other168(91%)4(7%)Perform compressions142(77%)8(15%)Manage code cart(16%)108(59%)35(64%)Perform defibrillation87(47%)40(73%)Obtain IV access84(46%)26(47%)Administer cardiac medication51(28%)42(76%)Prepare cardiac medication52(28%)26(47%)Alert/update family on status48(27%)0(0%)Prepare intubation medication36(20%)28(51%)Prepare laryngoscope/endotracheal tube for intubation34(19%)4(7%)Provide ventilations22(12%)1(2%)Administer intubation medication19(10%)34(62%)Interpret code algorithms6(3%)7(13%)Serve as team leader1(1%)0(0)Perform intubation0(0)1Role Clearly Defined (N 211)n 158(2%)n rHow Was Your Role Assigned? (N 221)n 168n 53Team 2%)1(4%)OtherTeam Member Roles Clearly Defined (N 220)n 168Alwaysn %)Occasionally57(34%)17(33%)6(4%)2(3%)NeverCC n 34, 62%) and simulationtraining as a team (MS n 126, 69%;CC n 33, 60%) would provide thebest learning opportunities andincrease their skill and confidence.See Table 4 for additional data.314%Critical Care NursesNumber/PercentageDiscussionPerception of RoleTeam performance can beenhanced by the early and appropriate identification of each teammember’s role during a resuscita-tion (Jackson & Grugan, 2015).Nurses are often first respondersand their roles are self-assigned,which may account for their perceived role clarity. Medical-surgicalnurses in this study identified theirroles as providing first responderSeptember-October 2015 Vol. 24/No. 5

Nurses’ Perceptions of Role, Team Performance, and Education RegardingResuscitation in the Adult Medical-Surgical PatientTABLE 3.Perceived Effectiveness of Communication Skills, Teamwork Skills, and Team PerformanceMedical-Surgical NursesNumber/PercentageHow Often Did Team Members Demonstrate Effective:nCommunication Skills (N 216)%Critical Care NursesNumber/Percentagenn 163%n Teamwork Skills (N 220)n 168n m Performance (N 239)n 184(0)n 55Team members asking each other for help171(93%)47(86%)Communicating respectfully150(82%)44(80%)Appropriate tone of voice150(82%)44(80%)Team leader receptive to new ideas169(92%)46(84%)Verbalizing a new treatment plan171(93%)40(73%)58(32%)15(27%)Debriefing post codeTABLE 4.Educational Experiences (N 239)Medical-Surgical NursesNumber/Percentages(n 184)nCritical Care NursesNumber/Percentages(n 55)%n%Education/CredentialingBasic life support181(98%)53(96%)Advanced cardiac life support114(62%)54(98%)Mock code simulation training73(40%)19(35%)104(57%)55(100%)Unit-based mock codes142(77%)34(62%)Simulation training as a team126(69%)33(60%)Training as a team outside simulation labOnline code resuscitation competencyEducational Preferences to Improve Skill and Confidence118(64%)32(58%)Simulation to practice skills only86(47%)19(35%)Lectures38(21%)15(27%)Online training55(30%)12(22%)Case studies74(40%)22(40%)September-October 2015 Vol. 24/No. 5315

care. These roles included performing compressions, defibrillating thepatient, managing the code cart,recording events, supporting family/significant others, and initiatingintravenous (IV) access. In theseroles, they provided initial treatment to critically ill patients.Critical care nurses identified theirroles as related to care and treatment provided in the critical caresetting. These roles included preparing and administrating cardiac andintubation medications, performing defibrillation, and managingthe code cart.Nurse respondents in this studydid not identify with some teammembers’ roles. Medical-surgicalnurses did not choose roles associated with ACLS or roles they considered to be beyond their nursingabilities. Because clinical nurses donot order medications and may beunfamiliar with some IV medications, preparation of medicationsfor intubation would be less familiar and thus would be delayed untilan anesthesiologist or appropriateteam member arrived to orderthem. With other code team members available to prepare medications, medical-surgical nurses maynot have acquired competency inthis area. Critical care nurses didnot identify with the followingroles: alerting/updating family onpatient’s status after resuscitation,providing ventilations, performingintubation, and serving as teamleader. Because critical care nursesare unfamiliar with the medical-surgical patient and family, they maybe uncomfortable providing apatient update. While providingventilations is an important function, critical care nurses may determine this role can be delegated toanother team member and be performed safely while they take rolesmore consistent with their dailynursing functions. Intubations areperformed by a team member competent in that area and within thescope of practice; the critical carenurses responding to this study didnot identify this role as one theywould perform (Jackson & Grugan,2015; Porter et al., 2014). Criticalcare nurses did not indicate their316role was to be a team leader. Thisrole is reserved generally for aphysician (Lauridsen et al., 2015).Team Performance,Communication, andTeamwork in ResuscitationEffective team performance iscontingent on communication andteamwork (Hunziker et al., 2011).Findings indicated nurses frommedical-surgical and critical careareas perceived their code team performance to be proficient as evidenced by members’ effective communication and teamwork. Respondents in this study percei

Medical Center, Boston, MA. . CNS,is Associate Professor, Connell School of Nursing, Boston College, Chestnut Hill, MA; and Nurse Scientist, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, MA. Natalie Fealy, MSN, RN, CCRN, CCNS,is Legal Nurse Consultant, DeLuca . Literature Review A review of the research litera-ture was conducted using .