Transcription

FEMINIST PERSPECTIVES ONDEVELOPMENT: WHY LEPR OSY ISA FEMINIST ISSUEDr. Margo t Wilson-M ooreDepartment of AnthropologyCAPI Research Fellow 1995-96University of V ictoriaOccasional Paper #9April 1996

Table of ContentsAbstracts . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1I.Introduction . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 2II.Developmen t Theory . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 3III.Theories of Women's Subordination . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5IV.Women and Development Research . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6V.Feminist Critique of Development . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 6VI.Women and D evelopment in Bangladesh . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 9VII.DBLM--A C ase Study . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 10VIII. Discussion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 14IX.Conclusion . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 16

1FEMINIST PERSPECTIVES ON DEVELOPMENT:WHY LEPROSY IS A FEMINIST ISSUEAbstractsThe roots of the feminist critique of M odernization and W orld-systems theory arefound in more general feminist perspectives on the status of women. This perspective hasmuch to offer in terms of its ab ility to open the do or to asking new and different questionsabout women's roles and their participation in the development process. At the centre ofthe femi nist d ebat e are juxt apo sed u nive rsali st an d no n-un iver salis t pos ition s on w ome n'ssubordination. The underlying assumptions regarding the nature of women's status vis-avis men inherent in these positions have had a substantial impact on what researchersconsider to be important and/or appropriate foci for research energies. Similarly, in thedevelopment arena these perspectiv es have influenced the ways in which developmentproblems are defined, the kinds of data collected, the ways in which results are reportedand the types of recommendations made. In the early stages, feminist scholars concernedwith issues of development discovered that little information was available regardingwom en's lives. Imm ediately, a c all wen t out for m ore (an d better) data. N ow, however,as increasing amounts o f information becomes available the time is approp riate to take amore analytical approa ch, one w hich contr asts various aspects of women's lives as theyrelate to deve lopmen t proces s. A case study drawn from my own research at the DanishBangladesh Leprosy M ission (DB LM) in northwest Bangladesh demonstrates the ways inwhich bringing a clea rly arti cula ted f emin ist pe rspe ctive to be ar on que stion s of w ome n'splace in development provides a more comprehensive analysis.

2FEMINIST PERSPECTIVES ON DEVELOPMENT:WHY LEPROSY IS A FEMINIST ISSUEI.IntroductionIn the years since the emergence of Modernization and World-systems theories1, it becameincreasingly clear that development initiatives predicated on these theories did not alw aysfollow a replicable or even predictable pattern and that many popular concepts andstrategies needed rethinking. D espite high expectations and good intentions, developmentprograms not only failed to improve local conditions but in many cases had extremelydeleterious effects on the people they were intended to help. Increased militarization,escalating national debts, decreased food production, high infant mortality rates, runawaygrowth of urban centers which lack basic services, and the general failure of developmentprograms to improve the lot of the poorest sectors of developing nations evidenced thefailure of programs to consider the social repercussions of change. Predicated on the beliefthat technolog y liberates people, both M odernization theory and W orld-systems theoryignore women entirely or assume that the "trickle down" effects of more generaldevelopment processes will have a beneficial impact on them. The feminist critique ofdevelopment theory followe d quickly on the heels of this oversight and in the decades sincethe first feminist critique was written (Boserup 1970), feminist scholars have generated avast and critical literature on women and development (cf. Arizpe 1977; Dauber and Cain1981; Dixon 1978, 1985;Dixon-Mueller 1985; Lewis 1981; Staud t 1978; Tinker,BoBramsen and Buvinic 1 976). The roots of the feminist critique of Modernization andWorld-systems theory are found in more general feminist perspectives on the status ofwomen and the lively and diverse nature of the women and develoment dialogue is1I use the term developmen t as an umbrella term encompassing both Modernizationand World-s ystems theory. Similarly, I use the term feminist criti que ofdevelopment theory to refer to the various feminist critiques of Modernization andWorld-systems theory and women and development as a generic which encompassesmore specific terms such as development for women or women in development(WID).

3reflective of the debate among those underlying feminist theories.As a context in which to consider th e feminist critiqu e of develo pment theo ry as itaddresses the lack of focus on women and as it is informed by more general feministtheoretical perspectives, I present a brief overview of Modernization and World-systemstheory in the sections which follow. The feminist critique of development theory has muchto offer in terms of its ability to identify with and present the "insiders" viewpoint. It opensthe door to asking new and different questions about women's roles and their participationin the development process. As an example, I review the state of the art of Women andDevelopment research in Bangladesh and provide a case study drawn from my research atthe Danish-Bangladesh Leprosy Mission in northwest Bangladesh which demonstrates thebenefit of bringing a clearly articulated fe minist perspective to bear on questions ofwomen 's place in dev elopment.II.Development TheoryHarrison (1988:1) has argued that there is no one modernization theo ry, rather the termrepresents a "shorthand for a variety of perspectives that were applied by non-M arxists tothe Third World in the 1950s and 1960s" (cf. Harbison and Myers 1964, Hoselitz 1960,Lerner 1958, Levy 1966, Moore 1965, Rostow 1969, Smelser 1970).Theoreticalperspectives on evolutionism, diffusionism, structural functionalism, systems theory, andinteractionism combined to form a constellation of ideas that became known asModernization theory. Primary tenets of Modernization theory include:1.Mod ernity and tradition are considered to be exclusive categories. The two mayexist (uneasily) side by side in "dual societies," but only for short periods of time.2.Develo pment occurs in a unilineal progression of stages of which Westernindustrialization and modernity represent the epitome . Third World nations eitherrepeat the developmental history of Western countries or they do not develop.3.The nation-state represents the appropriate unit of analysis, the "whole" withinwhich constituent parts are considered.4.Poor conditions in developing nations are due to inadequate training and lack of

4appropriate institution s. Western techno logy and training should be provided to"modernizing elites" who are the innovators and agents of change.5.Benefits from development will "trickle down" from the elites to the masses.Dependency theory was an outgrowth of the dependencia school w hich origina ted inLatin America in the 1960s and was quickly subsumed into World-systems theory. GunderFrank (1966), and others (cf. Be ckford 1972, D os Santos 1970 ), criticized Modernizationtheory for predicating its policies on the assumption that the historical and economic stagesof Europea n and N orth American capitalist development are similar to those experiencedin Third World nations. On the contrary, they argued, developed countries were neverunderdeveloped, merely undeveloped, and the economic, political, social, and culturalinstitutions present in underdeveloped nations today came about as the products ofcapitalism as it spread throughout the world.Understanding the exploitation ofunderdeveloped nations by capitalist nations requires "a comprehensive analysis of thecapitalist system as a whole.[an d the] simultan eous gen eration of un derdevelo pment insome o f its parts a nd of ec onomi c deve lopmen t in other s" (Fran k 1966 :17).World-systems approaches expand upon the formulations of Dependency theory butcriticize it for failing to consider the implications of class (cf. Amin 1976; Chase-Dunn1975, Portes and Walton 1981, W allerstein 197 4). Rooted in theories of impe rialism, aworld-systems perspective views developm ent and un derdevelo pment as atte ndant asp ectsof the same process. The occurrence of the former is dependent on increases in the latter(Harrison 1988). Central concepts in the World-systems perspective include:1.The unit of analysis should be the world economic system from which all so cial,cultural, and political processes are derived.2.The causes of underd evelopment are external to T hirdWo rld countries and areprimarily the result of ex panding c apitalist trade networks and the internationalsystem of exchange.3.Unequ al exchan ge allows disparity of military and ec onomic power between coreand periphery nations and th e existence of a capitalist w orld system prev entsautonomous, self-sustaining industrial growth in the Third World.

54.Transnational companies are the purveyors of both capitalism and neo-colonialismand represent the conflicting interests of both national and international groups.5.Development occurs in the Third World only when ties to the capitalist centers arebroken or weakened.III.Theories of Women's SubordinationAt the center of the feminist debate are juxtaposed universalist and non-universalistpositions on women 's subordination. Both groups have rejected the notion of women asthe passive recipients of culture and argue that women are social actors with personal goalswhich they strive to realize (c f. Lamphe re 1974; R osaldo and Lamphe re 1974; Roge rs1978, among others). Similarly, both groups agree that women's political and economicautonomy decline d with t he dev elopme nt of state organi zations . Nevertheless, they holdfundame ntally different assumptions concerning the nature of wome n's status prior to s tateformation (Atkinson 1982). One group of scholars maintains that women have beenuniversally and perp etually subordinated to men, while another group argues that this is notthe case, citing his torical and eth nograph ic examples of egalitarian societies w here womenand men enjoy equal status. These underlying assumptions have had a substantial impacton what researchers in each group consider to be important or appropriate foci for research.Feminists who ac cept the un iversal subordinat ion of w ome n as sum e th at m ale s ha ve a lwa ysbeen dominant and, acco rdingly, are less concerned with documenting male roles than withdiscovering and documenting the mechanisms of sexual differentiation. Although womenare viewed a s universally subo rdinated, they are not considered to be submissive andresearch focuses primarily on female groups and documenting the ways in which they wieldpowe r and in fluence (Roge rs, 1978 :138).Alt ern ativ ely, those feminists who have rejected the universal subordination ofwomen have assumed sexual differentiation of roles in which the relative power of malesand females varies. Accord ingly, these researc hers have been con cerned prim arily withidentifying and meas uring cross -cultural differences in female status.Historicalprecedence of egalitarian relationships between the sexes is an integral part of this

6approach and the paucity of ethnographic accounts regarding women has been a majorconce rn to the se scho lars (Ro gers 19 78:147 -8).Recen tly, the significan ce of this deb ate and its appropriateness for interpreting andunderstanding the life experiences of women throughout the world has come under closescrutiny (cf. Ros aldo 19 80; Atk inson 1 982; S chepe r-Hug hes 19 83). Nevertheless, recentvolumes still reflect this dich otomy alth ough it may be mo re subtle (cf. M iller 1993,Brettell and Sargent 199 3).Further, the universalist/non-univ ersalist debate clearlyinforms the feminist critique of development theory as demonstrated in the discussionbelow.IV.Women and Development ResearchIn the developmen t arena, the debate has bee n less overt than in more academic feministcircles. Nevertheless, underlying feminist assumptions about women's subordination havehad a clear influence on th e ways in which problems are defined and results reported.Acceptance of women as universally subordinated has led to a specific focus on women,sometimes to the complete exclusion of men, and to an emphasis on the mechanisms ofsexual differen tiation. Rejection of women's universal subordination, on the other hand,has placed the emphasis on measuring female status cross-culturally and the effects ofwom en's economic participation on status. Both of these emphases have, in large part,resulted in a focus on women in the development literature as an ignored, invisible,underv alued o r misrep resente d resou rce.Feminist critiques of development theory exist in a lively and ongoing dialogue(rather than as Kuhnian paradigmatic shifts) and the delineation of feminist positions isneither as simple no r as distinct as su ggested in th e following discussion. N evertheless,I present a schematic of the feminist critiques of development theory here which articulatestheir groundings in both feminist theory and development theory.Representing thefeminist critique of de velopmen t theory in this way identifies the underlying assumptionsand provides a theoretical framework from which to pose new and different questionsabout women's development, questions which reach beyond mere description to allow amore analytical view of the interrelated aspects of women's day-to-day existence and the

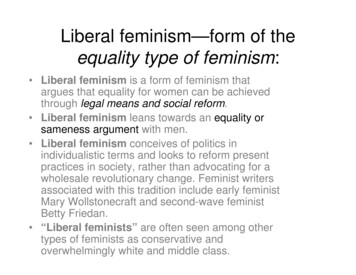

7impact of development planning on their lives.V.Feminist Critique of DevelopmentFigure 1 reflects the relationships between the various feminist critiques of developmentthe ory. The dichotomy between universalists and non-universalists is mirrored, for themost part, in feminist c ritiques which ca n be divide d into two camps. Lib eral feministshave primarily critiqued Modernization theory while Marxist feminists and socialistfeminists have con fined their criticism to Worl d-systems ( and D epend ency) theo ry. In onlyone case, the Liberal Dependency Critique, do liberal feminists critique World-systemstheory.The underlying feminist assumptions in each of these approaches determine thekinds ofquestions asked, the k inds of data collected and the kinds of recommendations made.Ac cor din gly, the liberal critique is founded in the feminist belief that women are andalw ays have been, in all places and all times, subordinate to men. It emphasizes thedisadvantages to and dis crimination against women which accrue from the failure ofModern ization theory to acknowledge women as a group w ith special nee ds. Out of th isperspective, two separate critiques have developed: the Liberal Feminist Critique, whichfavors the integration and equal participation of women in existing development programsthrough education and ch anges in the legal and ad ministrative systems; and the FemaleSphere Critique, w hich subsc ribes to the comple mentarity of male and female roles and thedelineation of public and private spheres, and advocates development programmingspecific to wom en, entire ly separate from tha t for men .The Liberal Fe minist Critique of World-systems theory is also informed by anacceptance of women's universal subordination. Nevertheless, it considers the globalsystem to be the appropriate unit of analysis and identifies capitalism as the force whichintroduces and reinforces inequality.As such, it provides a transitional critique ofdevelopment theory, a critique which in contrast to othe r liberal critiques s pecificallyemphasizes the impact of national dependency on women and the inc reas es in wom en'sexploitation which result from their incorporation into capitalist production activities.

8Although this critique favo rs the integratio n of wom en's issues into existing developmentprograms (like the Liberal Feminist Critique), it identifies mode of production as the mostimporta nt cons ideratio n in dev elopme nt plann ing for w omen.Alt ern ativ ely, critiques of World-systems theory come from Marxist feminist andsocialist feminist scholars whose theoretical perspective rejects universal femalesubordination. The Marxist Feminist Critique associates the declining status of womenwith chan ges i n mo de o f pro duc tion and view s wo men 's primary roles under capitalism asreproducers of the lab or force and as m embers of the re serve la bor forc e. This critiquefavors a socialist revolution and the elimination of domestic labor as a vehicle forliberatin g wom en.The Socialist Fem inist Critique, o n the other h and, view s patriarchy (in add ition tocapitalism) as the instrumental force in creating a political hierarchy in which women serveas consume rs, reproduc ers, and che ap laborers .This critique argues for a radicaltransformation of society and the elimination of class and sex hierarchies.

9VI.Women and Development in BangladeshEarly on, feminist scholars concerne d with broader areas of resea rch on w omen, as w ellas those concerned specifically with women and development, discovered that very littleinformation regarding wom en's lives was available. Immediately, a call went ou t for more(and better) data.Much o f the responsibility for collecting this data fell on socialscientists. As information became available, however, a second critical phase of analysisbegan. Feminist scholars began to construct models and test them using cross-culturaldata. For the first time, it became possible to make generalizations about wo men 'sexperiences and the rep ercussions of political, economic, social, and religious processeson their lives.Much of the Women and Development literature remains highl y descriptive innature, a derivative of early feminist emphases on collecting more and better informationabout the situation of women cross-culturally. All too often, however, Women andDevelopment researchers neglect to articulate their underlying feminist assumptions andtheorizing is left, in large part, to feminist acad emicians w ho usually rely on eth nograph ic(rather than development) literature for constructing and testing th eir models. A s a result,feminist theory and Women and Develop ment researc h have pr ogressed, in recent years,along separate and divergent paths. And, despite the actuating influence of feminist theoryon W omen and Development research and their common concerns with the situation ofwome n, disco urse be tween these tw o bodie s of literat ure is rem arkably sc ant.Women and De velopmen t research ten ds to be of a highly practical n ature,concentrating on the imm ediate and p ragmatic pro blems faced by women in developingnations, then directing resources and institutional support toward those identified needs.Feminist critiques of development theory revolve primarily around the failure ofdevelopment theory to address the issue of women directly. Women are either categorizedwith m en or ig nored a ltogethe r.A more analytical approach has important app lications in Bangladesh, w heredevelopment planning for women has become of primary interest to both governmental andnon-governmental development agencies.Bangl ade shi wo man in the f ollow ing wa y.Jahanara Huq (1985: v) characterizes the

10In all age groups, she is subject to red uced calo rie intake, groo med tocultivate habits of pa tience, subm issiveness an d accepta nce until sudd enlythrust into motherhood without any psychological preparation for a changedstatus. By the age sh e is 45, a con tinuous nu tritive maternal d epletion isalready underway due to unco ntrolled , repeate d pregn ancies. The entirelyhazardous demographic burden (burden of bearing, nursing and rearingchildren) is on womenfolk who have the least decision making power whento have children and in what number. So plagued by early marriage, ruralwomen are threatened by polygamy, separation, desertion, divorce,destitution and lastly violence all telling upon their physical and mentalhealth. A woman has to undergo the hazardous existence and is the chiefvictim not the win ner for her lif elong valuable silence, forbearance andsacrifice, imposed upon her by the societal norm.Thus characterized, the situation of women in Bangladesh is clearly an appropriatefocus for academic, development and feminist research.Aside from depicting thedeplorable state of women, this quotation also demonstrates the predominantly descriptivefocus of w ome n's studies in Bangladesh. Descriptive research has been well-suited to theneeds of the time (that is, until recently little information has been available) and the highlydescriptive nature of research o n wome n in Bang ladesh is less a criticism of th e scholarsh ipthan an indication of the present "state of the art." Now, however, as a substantia l bodyof information becomes available, the time seems appropriate to ask research questionswhich consider m ultiple aspects of women's experience, how vari ous s phe res o f wo men 'slives are interrelated, and what effect those relationships have on women's place in thefamily and in society. These types of questions go beyond description to contribute to ourunderstanding of the dynamic forces at work in the liv es of w omen. A research perspectivewhich determines not only how, but why and in what context, specific behaviours occurcould prove valuable as a g rassroots test of feminist theoretical models, as a tool forproviding more comprehensive information about women's lives and as a basis forappropriate development planning for women.

11VII.DBLM--A Case StudyThere are an estimated 136,000 leprosy patients in Bangladesh and some 10 millionworldwide--60 percent of whom live in Asia. The WHO has issued a directive calling forthe elimination of leprosy by the year 2000, in response to which, a country-wide leprosyprogram has been initiated in Bangladesh.Leprosy has always held a morbid fascination for me and I am particularly interestedin understanding the cultural context in which the behaviours (especially stigmatization)surrounding leprosy develop and the way in which the illness experience of patients isculturally constructe d (Wilson-Moore 1995). M y relationship with the Danish-BangladeshLeprosy Mission (DBL M) be gan in 1988 when, over a 6 month period, I used to visit at theDBLM hospital in Thakurgaon which was located about 12 miles from my dissertationresearch site in northwest Bangladesh. In 1991, I returned to Bangladesh and beganplanning and implementing a formal collaborative research project2 with the the FieldDirecto r of DB LM .W e held a series of four workshops for the DBLM staff intended to enhance thecollaborati ve aspects of the research. At the first one, we discussed what informationwould be most use ful to DBLM. This formed the basis for producing an interview format.The questionnaire addressed such issues as: 1) patient knowledge of leprosy and treatmentseeking history; 2) the patient's attitude toward the disease, at first diagnosis and at prese nt;3) the nature of problems experienced in his or her personal, family, work, religious orcommun ity life; 4) the attitude and behaviours of his or her family following diagnosis; and5) the attitudes and behaviou rs of his or her community. Additionally, patients wereencouraged to suggest what would best help leprosy patients in overcoming their problems,and to discuss what advice they would giv e to oth er indi vid ual s with and wit hou t lep ros y.Fin ally, patients were given the opportunity to raise any other issues not already consideredin the course o f the intervie w. The questions were op en-ended and the questionnaire2Funding for this research was prov ided by the Centre for Asia-Pacific Initiatives atthe University of V ictoria and DANID A through the Danish-Bangladesh LeprosyMission.

12require d 45 to 9 0 minu tes to ad mister.At the second workshop, I taught DBLM field workers and medical andrehabilitation officers how to do ethnographic interviewing and we field tested thequestionnaire.At the third work shop, the interviewers discussed their experiencesinterviewing patients givin g them an o pportunity for them to "debrief," to discuss thechallenges of data collection, to review d ata not reco rded on th e questionn aires and to " tellstories" about th eir intera ctions w ith patien ts. At the fourth workshop, I provided apreliminary analysis of results from a sub-sample of interview s and the interviewers w ereasked to discuss and interpret the results. A total of 200 interviews were collected andentry of these data to the computer is now complete, however, the analysis of the entiredata set is still in the early stages. Consequently, the results presented here are based onthe subsample of 79 interviews and the discussions which took place at the final workshop.In the sections which follow, I discuss the nature of leprosy disability as experienced bythe patients themselves. These are by no means the objective assssments o f disabilityroutinely utilized by medica l practitioners d iagnosin g le pro sy in the field 3 or by theInternational Classification of Impairme nt, Disability and Handicap (ICIDH) set out by theWHO 4. These self-re por ts d o, h ow eve r, re pre sen t the ac tua l ex per ien ces of lepr osy patientsand ref lect the p rofoun d impac t of lepro sy on their liv es.I present numerical and proportional representations of patient disability as they arereported by the whole sample and by male and fem ale patients ind ividua lly. A computed3Leprosy field w ork ers rou tinely u se a three grade system to measure and describedisabilities for epidemiological purposes (0 no dis ability, 1 anaesth esia only withno visible deformity or damage, 2 v isible deformity or damage).4The ICI DH def ine s "impa irm ent " as any loss or abnorm ality of psychological,physiological or anatomical structure or function; "disability" as any restriction orlack of ability (resulting from impairment) to perform an activitiy in a mannerconsidered normal for a human being; and "handicap" as a disadvantage for a givenindividual resulting from impairment or disability, that limits or prevents fulfillmentof a role tha t is norm al for the age, sex , social and cultural situation of thatindivid ual.

13disability score (based on these self-reported disabilities) indicates that women tend to bemore disabled than men. I consider these differences in male and female patients'disabilities and in the problems which they face on a daily basis as indicative of pervasiveattitudes toward lep rosy in general an d female lep rosy patients in particular. I argue thatleprosy has a significant cultural c ompone nt which h as been larg ely overlooked inbiomedical research, but which cannot continue to be disregarded. Beyond this, bybringing a feminist perp sective to be ar on the issu es of leprosy patients, it is possible todemonstra te differential disability of female patients as a clear reflection of patriarchalvaluing (or more appropriately devaluing) of women generally and of women with leprosyin partic ular.Table 1 pr ovi des a de scr iption of the t ypes of d isabilitie s re por ted by leprosypatients. Frequencies and proportions are given for all patients in the sample and for malesand fem ale s se par ate ly.The proportion of males (68%) to females (32% ) in the leprosy patient population(a 2:1 ratio) is partially explained by the differential morbidity of male patients, that is, menare more apt to get leprosy than w omen (see Neylan et al, 198 8 for similar find ings inThailand).This circumstance is exacerbated by the preponderance of males in thepopulation of Bangladesh (126:100 sex ratio). Research in general hospital settingssimilarly indicates that male patients routinely outnumber female patients at all ages(D'Souza and Chen 1980). For adults, this means that men are more apt to receive medicaltreatment. For children, this means that families attend to the medic al needs of m alechildren first. Fo r leprosy patients, this means that males come for treatment more oftenand ea rlier in the course of the d isease th an do fe males.Table 1 - Disability by SexDisa bilityTotalM aleFem ale

14No n 52%36%C l a w Han dFo o t Dro pAm p u t atio nL a g o p hth alm o sUlcerMCR(special shoes)** 101628%8%4%0%4%24%1215%611%624%*255479* ** T O TA L**The p ropo rtion of resp onde nts w ho rep ort on ly patch es and no ot her di sabil ity.Other includes shortening of feet, absorption, wrist drop, thickened earlobes, wrinkled skinand collapsed nose.***Percents for individual disabilities do not add to 100 percent because of multiple responses.Table 2 pr ovi des a di sab ility sco re c omp ute d by assignin g a score of 1 for everydisability reported by the patients. The difference between m ale and fem ale patients indisability score isstatistically significant at p .0257 (using chi square). In particular, female patients areunder-rep resented in th e group w ith no disability and over-repre sented in the group w ith2 dis

problems are defined, the kinds of data collected, the ways in which results are reported and the type s of recommendations made. In the earl y stages , feminist scholars concerne d with issues of development discovered that little information was available regarding women's lives. Immediately, a call went out for more (and better) data.