Transcription

be love nowthe path of the heartram dasswith rameshwar das

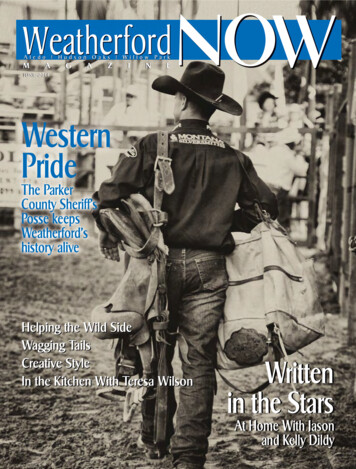

Maharaj-ji. Photo by Balaram Das.To Maharaj-jiA man in a blanket who diedbut lives within meand always knows my heart,a cosmic playmate whoselaughter goes beyond time,who always loves me more,more than a lover, father, ormother,more than I love myself,even when I forget to lovehim,

whose presence is like asweetsilent mistlike energy in myheart,who showed me a pathwith no directionand illumines every stepalong the way,without whom none of thiswould exist.Through him I met my realself.He wouldn’t take credit forthis book, but it is his.

ContentsCoverTitle PageForeword: Getting Here from There, byRameshwar DasChapter 1 - The Path of the HeartChapter 2 - Excess BaggageChapter 3 - To Become OneChapter 4 - DarshanChapter 5 - GuidesChapter 6 - Remover of DarknessChapter 7 - The Way of GraceChapter 8 - A Family ManChapter 9 - One in My HeartCredits and PermissionsAdvance Praise for Be Love NowCopyrightAbout the Publisher

Getting Here from ThereRameshwar DasSPRING,1967. I was twenty, a sophomore atWesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. Ihad just spent my first extended time out of thecountry on a semester abroad in Franco’s Spain.The Vietnam War was raging, and there wasupheaval on campus.Freshman year I took a seminar, “Freedom andLiberation in Ancient China and India,” that stirred aninterest in Taoism and Buddhism. At the same time,I started smoking pot and experimenting withmescaline, DMT, and LSD. The visual and lyricaleffects of psychedelics stimulated my artistic,philosophic, and poetic intuitions and expanded myinner and outer horizons. They didn’t improve myacademic standing.

That spring a flyer appeared for a guest lecture byRichard Alpert, Ph.D., formerly a psychologyprofessor at Harvard, who had done some of hisgraduate work at Wesleyan. Two of his formerstudents, Sara and David Winter, were teachingpsychology at Wesleyan and had invited him tospeak.Alpert was vaguely notorious to me as anassociate of Timothy Leary, a counterculture icon.They had both been fired from Harvard in connectionwith their psychedelic activities. Alpert had thedistinction of being the only tenured professor everpublicly exorcised from Harvard’s Ivy League faculty.They didn’t go quietly. Dr. Leary’s infamous 1960scommandment “Tune in, turn on, and drop out” hadbecome a media mantra and a cultural strategy. Potand acid made rapid inroads, displacing alcohol asdrugs of choice. The Beatles and the Stones trippedout, and there was an atmosphere of intrepid innerexploration and raucous fun mixed with politicaloutrage. Some of it was hedonism, some was dumb,and some of it became the bones of a generation.Dr. Alpert’s talk began at 7:30 P.M. in one of thestudent lounges. I expected a pep talk on “better

living through modern chemistry” (then an ad sloganfor DuPont Chemical). About fifty people attended,mostly students, spread out on couches, chairs, andthe carpet. Instead of a tweedy Harvard psychedelicpsychologist, the speaker entered wearing ascraggly beard, sandals, and a kind of white robe ordress. Dr. Alpert had just returned from India, wherehis name had been changed to Ram Dass. He saidit meant “servant of God.” He looked like a soapboxprophet in Hyde Park, which I’d just seen in London.Instead of an opening paean to psychedelics, hebegan to relate his experience of living for sixmonths in an ashram in the foothills of theHimalayas. He described meeting a guru who had acataclysmic effect on his consciousness, so much sothat he sequestered himself for six months in theguru’s ashram to learn yoga and meditation. Thiswas too weird for a portion of even this avidaudience, and before long some departed. After awhile, someone turned out the lights, and Ram Dasscontinued to talk in womblike darkness. In the dark,his disembodied voice fairly crackled with a kind ofenergy that permeated the room. He combined theexcitement of a scientist with a new discovery and

an explorer in terra incognita. He continueddescribing his experiences and responding toquestions until 3:30 A.M.As Ram Dass spoke of the interior transformationhe had undergone, I began to experience one too.Subjectively it was like a figure-ground flip when, inone of those high-contrast images, you suddenly seethe space instead of the shape. In my case I wentfrom being the center of my universe to seeingmyself as just one spark of awareness amongbillions. I understood in that moment that we are allon an evolutionary journey toward realization throughinfinite time and space.It was more than a conceptual understanding.There was a feeling of meeting together in a deepspace of love, and compassion for what Ram Dasscalled “our predicament.” Two and a half years later,when I traveled to see the guru in India, I experiencedprecisely this feeling again, like déjà vu. However ithappened, an old man in a blanket, whom I alsocame to call Maharaj-ji, came through Ram Dassthat evening. The abode of love, compassion, andoneness in which the guru lived had movedtemporarily to Connecticut.

To a twenty-year-old on an intensely personalquest for identity, this was revelatory. The idea thatthere were other beings who had actually made andcompleted this journey of inner exploration that I hadonly imagined was astounding. Maybe the journeywasn’t quite so personal after all.The next day I sought out Ram Dass and visitedwith him at the Winters’ home. Something hadclicked that needed further exploration. Whatever Ihad experienced, I wanted more of it. I have almostno recollection of what was said between us in thatexchange. I know I felt awe and gratitude, though aswe talked I realized Ram Dass was very much on hisjourney, as I was on mine. Later I came to realize hesometimes had a difficult time when peopleassociated him with the transmission of that state.What could he say? “Sorry, that wasn’t me talking”? Ithink it drove him to work harder on his own “stuff.”He was always completely, refreshingly out frontabout his own desire system and need for approval,and he used his neuroses as “grist for the mill.”Rather than sweep things under the rug, he used themeanderings of his psyche as humorous fodder for

his talks. There was no “holier than thou.” It was morewholly than holy, more practical than pious. I thinkother people, too, appreciated how Ram Dass usedhimself as a case study for his inner research. Theconfluence of his psychological training, hisopenness from psychedelics, and his synthesis ofEastern religion made him a perfect resource forconsciousness evolving during the upheaval of the1960s. He managed to bring it together inunderstandable language. And it didn’t hurt that hetold a good story.Over the next two years I drove up periodicallyfrom Wesleyan to visit Ram Dass, following I-91 fromConnecticut through Massachusetts to where he wasstaying at his family’s summer place, a farm on alake near Franklin, New Hampshire. In warm weatherhe stayed in a tiny guest cottage without water orplumbing that he made into a cozy retreat, or kuti,where he meditated, practiced yoga, and cooked adaily pot of khichri, rice and lentils mixed together. Inthe winter he moved into the servants’ quarters of themain house in the attic over the kitchen.Ram Dass taught me the basics of yoga andmeditation and recommended some of the writings

of the saints and yogis he had come to know of inIndia. Pranayama (breath energy practices) andsaying mantras (sacred syllables) became part ofmy routine. I learned to cook khichri and makechapatis, Indian flatbread.Ram Dass’s father, George Alpert, was a lawyerwho had been president of the New York, NewHaven, and Hartford Railroad. He and his fiancée,Phyllis, were often at the house when I came up tovisit Ram Dass in Franklin. They were extraordinarilyhospitable, and I felt like extended family. ClearlyRam Dass’s new manifestation had left them at aloss after his career at Harvard, but they loved whohe had become, and they didn’t really care why.George continued to call him Richard and seemedbemused by the assortment of mostly young peoplewho kept turning up. It was all a bit of a mystery, butthe love had infected them too.Although he was mostly a hermit that year, in 1967Ram Dass also gave a talk at the Bucks CountySeminar House in Pennsylvania. In Franklin, alongwith his daily sadhana, or spiritual practice, heworked on a manuscript about his experience inIndia. In the winter of 1967–68 he gave an extended

series of talks at a sculpture studio on the East Sideof Manhattan. The same people showed up nightafter night, often with friends. Others were beginningto be affected by the extraordinary energy andpresence that accompanied his talks.Ram Dass spoke with self-deprecating humor,using his own missteps as counterpoint to theintensely serious journey he was illuminating. Hisself-revealing honesty in facing his personal demonsand his delight in the absurdity of a Harvardpsychologist encountering Eastern mysticismbecame hallmarks of his presentations. He linkedhis psychedelic drug experiences, which many of ushad experienced by then, to the dissolution of theego in Eastern philosophy. And he used hisencounter with the guru as a model for attaining thehigher consciousness he now saw as the goal,enlightenment.Soon after graduation from college in 1969 I wasdrafted and called in for a physical. Bearded andhirsute, I stood in my underwear with a string ofprayer beads repeating a Hindu mantra during theentire day of prodding and poking. The psychologistwas the last station along the line, and by the time I

arrived at his station I had been praying with suchintensity I could hardly see. The psychologist, wholooked as though he was unhappily doing hisalternative service himself, disqualified me. I was putin a 1-Y and later a 4-F classification, which meantunfit for service. That left me free to join the youngpeople, students, hippies, flower children, and otherswho had heard Ram Dass in person or by word ofmouth and were arriving at the driveway in Franklin.My younger brother and sister went to the rockfestival at Woodstock while I meditated at yogi campwith Ram Dass.Outdoor weekend darshans, spiritual gatheringswith Ram Dass, evolved under a tree in the yard,with George’s gracious permission, into summercamp. We were a ragtag group of twenty to thirty onan “Inward Bound” adventure. Tent platforms and adarshan house went up in the woods above thefarm, and Sufi dances and yoga classes were heldon George’s beloved three-hole golf course. Groupmeditations and yoga were part of the dailyschedule, as Ram Dass sought to transfer hisexperience in India to this motley cadre of would-be

yogis. We made up with enthusiasm and love forwhat we lacked in disciplined renunciation. Bysummer’s end the weekend crowd under the treesnumbered in the hundreds. Some of the camperswere like ships passing in the night, some haveperished, and others are still in touch, nowgrandparents.Ram Dass’s painstakingly written manuscriptabout his India trip found no takers in the publishingworld. He continued giving public talks, and that fallhe drove cross-country to California to teach at anascent center for psychological and spiritual growthin Big Sur called Esalen. Esalen assigned himhousing with a writer and his wife, John and CattyBleibtreu. John noticed the transcripts from RamDass’s talks at the New York sculpture studio as hepulled the suitcase out of his car. He asked if hecould take a look. He thought there were some goodstories, and he checked off the ones he liked.From Esalen, Ram Dass drove to the LamaFoundation near Taos, New Mexico, a back-to-theland commune of artists and hippies that he hadhelped found before his trip to India. Steve Durkee, avisionary artist who had spearheaded an art group

called USCO in New York, was a friend and the mainman at Lama. He also noticed the transcript andasked what it was. Over dinner with five or six of theresident artists at Lama, they brainstormed waysthat the passages John Bleibtreu had checked couldbe illustrated.During the fall and winter of 1969–70, Ram Dass,Steve, and the Lama commune went to work onmaking Ram Dass’s words into text art. At his talksRam Dass gave out postcards that people couldsend in to Lama to get a copy of whatever emerged.I even did my part and copied some of the photos ofsaints Ram Dass had brought back from India.In early 1970 the Bountiful Lord’s Delivery Serviceat Lama mailed out several thousand copies of atwelve-by-twelve-inch corrugated box, the contentsand printing of which were financed from theproceeds of Ram Dass’s lectures. It was distributedat no charge. In the box was a core book from thetranscripts called From Bindu to Ojas (Sanskrit for“From Material to Spiritual Energy”). It was printedon brown paper and hand bound with twine. Includedwere a booklet about Ram Dass’s journey to theguru titled HisStory, a section of spiritual practices

called the Spiritual Cookbook, holy pictures to putup on your refrigerator or altar (some of which arereproduced in this volume), a book list calledPainted Cakes, and an LP record of chants andspirituals from the contemporary scene. It was a truedo-it-yourself kit for a spiritual journey.The summer of 1970 saw a brief revival of the yogicamp at Franklin. After Ram Dass had been on theroad and lecturing for a year, the numbers began tobe overwhelming for George’s farm. But from thoseevanescent groups came the genesis of a Westernsatsang, a community of seekers.Ram Dass continued to lecture and travel, but wasmindful that Maharaj-ji had told him he could return toIndia in two years. (Maharaj-ji is a common honorificin India that literally means “great king.” In this bookMaharaj-ji usually refers to Ram Dass’s guru, NeemKaroli Baba, because most of the time that’s how hewas addressed.) Finding himself beginning to burnout after all the public exposure, Ram Dass wasthinking about goi

ram dass with rameshwar das. Maharaj-ji. Photo by Balaram Das. To Maharaj-ji A man in a blanket who died but lives within me and always knows my heart, a cosmic playmate whose laughter goes beyond time, who always loves me more, more than a lover, father, or mother, more than I love myself, even when I forget to love him, whose presence is like a sweet silent mistlike energy in my heart, who .