Transcription

THE DEVELOPMENT OF NURSING EDUCATION IN THEENGLISH-SPEAKING CARIBBEAN ISLANDSbyPEARL I. GARDNER, B.S.N., M.S.N., M.Ed.A DISSERTATIONINHIGHER EDUCATIONSubmitted to the Graduate Facultyof Texas Tech University inPartial Fulfillment ofthe Requirements forthe Degree ofDOCTOR OF EDUCATIONApprovedAcceptedDean of the Graduate SchoolAugust, 1993

ft 6J801- o,. /;.C ? /c-j/ /ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS; o. l yrr 7 7C I would like to thank Dr. Clyde Kelsey, Jr., for hisC'lp ' unflagging support, his advice and his constant vigil andencouragement in the writing of this dissertation.I wouldalso like to thank Dr. Patricia Yoder-Wise who acted asco-chairperson of my committee.Her advice was invaluable.Drs. Mezack, Willingham, and Ewalt deserve much praise for themany times they critically read the manuscript and gave theirinput.I would also like to thank Ms. Janey Parris, SeniorProgram Officer of Health, Guyana, the government officials ofthe Caribbean Embassies, representatives from the CaribbeanNursing Organizations, educators from the various nursingschools and librarians from the archival institutions andlibrariesindividualsin Trinidadagreedand Tobagoto face-to-faceand Jamaica.interviews,Theseansweredtelephone questions and mailed or faxed information on aregular basis.Much thanks goes to Victor Williams for hiscomputer assistance and to Hannelore Nave for her patience intyping the many versions of this manuscript.On a personal level I would like to thank my niece EloiseWalters for researching information in the nursing librariesin London, England and my husband Clifford for his belief thatI could accomplish this task.11

TABLE OF CONTENTSACKNOWLEDGEMENTSiiABSTRACTviLIST OF TABLESviiiLIST OF FIGURESixCHAPTERI.INTRODUCTION1The Caribbean AreaII.STATEMENT OF THE PROBLEM14Conceptual Framework9Purpose of the Study13Delimitations and LimitationsIII.of the Study18Assumptions19Definition of Terms19MethodologyIMPACT OF EUROPEAN NURSING EDUCATION ONCARIBBEAN NURSING EDUCATION PRIOR TO THERENAISSANCE AND REFORMATIONSummaryIV.2635THE EMERGENCE OF A NEW ERA OF LEARNING THERENAISSANCE AND THE REFORMATION--IMPACT ONCARIBBEAN NURSING EDUCATIONSummaryV.223745THE BEGINNING OF EUROPEAN EXPLORATION ANDEXPANSION--IMPACT ON CARIBBEAN NURSINGEDUCATION47The Colonial Period53Summary60111

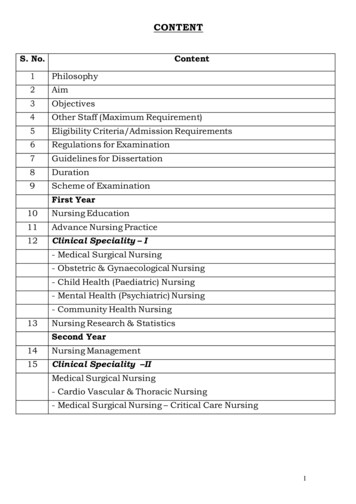

VI.CARIBBEAN NURSING EDUCATION IN TRANSITION.62Current Educational Programs73Nursing Schools in Jamaica82Nursing Schools in St. Lucia83Nursing Schools in Trinidadand Tobago84Caribbean Nursing Schools—TrendsVII.in Unification85Summary87DEVELOPMENT OF PROFESSIONAL NURSINGORGANIZATIONS IN THE CARIBBEAN AREA90The Nurses Association of Jamaica90The Caribbean Nursing Councils93The Trinidad/Tobago NursingVIII.Council93The Caribbean Nurses Organization95The Regional Nursing Body97Contributions of Caribbean Nursesto the International ArenaContributions to the Larger101International Arena102Summary107CONCLUSIONS114Projections for the Future123Recommendations for Further Study125127REFERENCESAPPENDICESA.INTERVIEW AND SURVEY QUESTIONNAIRES,LETTERS TO EMBASSIES AND CARIBBEANNURSING SCHOOLSIV134

B.C.JAMAICA NURSING SCHOOLS AND AREAS OFSPECIALIZATION173PROCEDURE FOR EVALUATION AND APPROVAL OFSCHOOLS OF NURSING WITHIN THE REGIONALNURSING BODY185

ABSTRACTDuring the past several hundred years, historians modalities that were implemented to meet the exigencies of cientific trends, technological developments and velopments in Europe, Asia, and North America.of theCaribbean area,thereis verynursingIn the caselittleliteratureregarding the developments of nursing and the teaching ofnurses; the fragmented information that is available, however,seems to convey a long adaptive process from Arawak existenceto the current modern nursing educational system.The primary objective of this study was to identify thevarious factors, processes and people that influenced spiritualistic rites and rituals in the care of the sick andin the education of nurses, to the modern scientific approachcurrently used in the Caribbean area, which is comparable tomore developed countries.Besides the adaptation over time,the study looked for new trends in nursing education in theCaribbean area andidentified the projections of nursingeducators for the future and the contributions that Caribbeantrained nurses are currently makingarena.VIto theinternational

An extensive search for historical material was donethrough the Central Library of Trinidad and Tobago; the WestIndian Reference Library in Trinidad; The World College ofNursing Library in London, England, the Jamaica Archives, theJamaica Institute, The Daily Gleaner, The Jamaican Nurse,Index Medicus. the International Nursing Index, the CumulativeIndex to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and the NursingStudies Index.Embassies.Questionnaires were sent to all the CaribbeanStructured telephone and face-to-face interviewswere also done.Results from the study indicated a protracted course ofevents from spiritism, through an era of British brutality andservant girl approaches to modern nursing education. cant factors in this adaptive process.emergedasIn addition,significant contributions made by Caribbean nurses to theinternational arena through collaboration with various worldhealth organizations were documented.vii

LIST OF TABLES1.2.Regional Nursing Body English-Speaking Schoolsin Caribbean86Presidents of the Nursing Associationof Jamaica92Vlll

LIST OF FIGURES1.General Adaptation Syndrome Model92.Process Model of Stress and Adaptation103.Adaptation on the Life Continuum114.Historical Time Line of the Developmentof Caribbean Nursing Education1095.Nursing Education Sponsorship1786.University Hospital of the West IndiesCourses184IX

CHAPTER IINTRODUCTIONThe Caribbean AreaThere is little recorded information on the history stand the development of nursing in this region however,one needs to have some knowledge of the Caribbean territory.The Caribbean area is a number of islands in a seabetween North and South America.Columbus in 1492.They were discovered byThis island chain measures approximately1800 miles long and between 400 and 700 miles wide.Theislands are bordered by the Gulf of Mexico on the North, andthe Yucatan Channel on the South and are clustered by theBahama Islands on the East. The Caribbean Sea which surroundsthe islands is navigable, facilitating transportation betweenislands, while also serving as a pathway to both the Atlanticand the Pacific Oceans.Although hurricanes are prevalent between the months ofJune and October, rain that follows generally abates the longperiods of drought, and therefore, much of the destruction bystorms is generally minimized and accepted by the inhabitants.The Caribbean area has many good natural harbors: Havanaand Santiago, Cuba; Kingston, Jamaica; the Mole, St. Nicholasand SamanaBay, Hispaniola;Castries, St. Lucia.San Juan,Puerto Rico;andThese harbors facilitate commerce andshipping internationally.

The Europeans migrated to the Caribbean Islands duringthe Reformation and Renaissance of the sixteenth century. tories and new learning. The early settlers concentratedon the development of the region not only agriculturally andsociologically, but also educationally which likely includednursing education (Roberts, 1940).Columbus' plan provided for Spain to have sovereigntyover the Caribbean Islands.England, France, and a host ofother countries, however, had other plans for the area.Inthe fifteenth century, the Caribbean waters were filled withEuropean pirates and buccaneers who fought for possession andsovereignty (Roberts, 1940).Saint Lucia changed hands fourtimes between the French and the British during the struggle.Barbados remained permanently British while Guadelupe andMartinique remained French.This admixture of peoples hasleft its imprint on the Caribbean area to this day.populationTheincludes people from nearly every nationality(Williams, 1970). The greatest number of people is of Africandescent, and in smaller numbers are Chinese, Indians, Germans,British, Spanish, Portuguese and Lebanese.Columbus described the Caribbean area as a land of gold(Roberts, 1940), but the islands were not devoid of problems.In his terms, the people were illiterate.Columbus could notunderstand their language nor could they understand Spanish.The island people represented two distinct groups: the Caribs

(after whom the Caribbean is named) and the Arawaks.Thebehaviors of the two groups were markedly different.TheArawaks were a peace-loving red-skinned people who wore onlyfeathers while the Caribswere aggressive andmurderous(Williams, 1970). These aborigines had no reasonable plan fornursingcarenor nursingEuropeans at that time.educationbutneither didtheThe aborigines practiced magic andused herbs for treatment of the many epidemics, such as yellowfever, which was then highly prevalent.

CHAPTER IISTATEMENT OF THE PROBLEMDuring the past several hundred years, volumes have beenwrittentoshowconditions.howpeopleHistorians havehaveadaptedelaboratedtochangingon nursingcarepractices and the teaching modalities that were implemented tomeetthe exigenciesof the times.These writings havedescribed primitive eras, scientific trends, dtheyhaveconcentrated on the nursing developments in Europe, Asia, andNorth America.In the case of the Caribbean area, there isvery little literature regarding the development of nursingand the teaching of nurses.The fragmented information thatis available, however, seems to convey a long adaptive geducational yaffectsoneBarzun (1983) contends that people requirehistory written by contemporaries whom they understand, sothat their minds may be filled and reshaped not for dealingwith crisis but for coping with day-to-day situations.Histheory lends emphasis to the need for the documentation ofnursing education in the Caribbean area.Abu-Saad (1979) cites a new trend which stresses theimportance of an international orientation and a multiculturalapproach to nursing and nursing education.4If this is to be

orical background information; they must show appreciationfor their historical past.Through strategic planning andimplementation they must incorporate historical events anddemonstrable activities that will produce the multi-culturalflavor (Abu-Saad, 1979).Nursing educators who fail to incorporate historicalcontent in their curriculum will be seeing the effort forinternational cohesion with eclipsed vision. These educatorswill fail to understand the unique contributions portrayed inthe chronologies of history in the vast arena of nursing andnursing education.Aeschliman (1973) postulates that the nature of nursingandnursingeducation"culturally defined."inagivenplaceorperiodisHence to both teach and practicenursing from a world perspective, one must input informationinto a circular historical concept.givengeographicalconcentricity.regionWhen information from ais missing,thecirclelacksWhen the circle is made complete through thesharing of historical information from country to country itwould be in-keeping with the goal of the International Councilof Nurses whichis to foster communicationamong nursesthroughout the world for mutual understanding and cooperation(Holleran, relative to the Caribbean area should focus specifically on

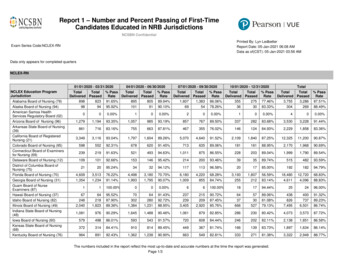

Caribbean area nursing education.Caribbean area nurses areconstantly traveling abroad to practice their profession. Forexample, during the ten year period 1959-1969, 3,034 nursesleft Jamaica to practice nursing in the United States, Canadaand/or the United Kingdom ("Nursing Council," 1969).Sincethere is continuous recruitment of Caribbean area nurses rnational Nursing," 1989), it is important that theyreceive the quality nursing education that will enable them escountries.thehostHistoricalcountrieseducational advisement over time is also crucial.withCaribbeannurses in foreign health care settings show that there is ribbean area may be of similar quality to that of the UnitedStates, Canada and Great Britain.According to "A FineRecord" (1961), nurses educated in the Caribbean area nursingprograms are as competent as nurses educated in more developedcountries.Recent data show that Caribbean area nurses pass theUnitedStates(NCLEX) atNationala higherCouncilonLicensurepercentage rateExaminationthan otherforeigngraduates; and Caribbean nurses traveling to Canada do equallywell with passing the Canadian examinations (National Councilof State Boards, 1992).With reference to Great Britain,reciprocity of basic nursing education, with the General

Nursing Council for England and Wales, was achieved by theNurses Association of Jamaica as early as 1952 (Swaby, 1980).Because of the Caribbean area trained nurses' ability ospitals and because of their high rate of success on alsemblance to nursing education in more developed countries.This represents growth in a nursing educational system thathad its vestige in the Tainos (an Arawak Indian Tribe), thewarring Caribs, pirating Spaniards, French, Dutch, BritishCompatriotsand Africanslaves(Williams, 1970).Theseproblems were further enhanced by economic deprivation, socialinequality and political dependence on Britain (Brereton,1981).Swaby (1980) postulates that:as one fearlessly looks back into the history ofCaribbean area nursing education one is "cheered bymemories of slow but sure progress, in the steepclimb from shoddiness and worthlessness to trueeducation for professionalism in nursing." (p. 35)Swaby also contends that there is a need for betterpreparation of teachers of nursing in the Caribbean area andadvocates that these teachers should have preparation at themaster's and doctoral levels.Currently they are providedadvanced course work in teaching and administration prior toteaching assignments, but this falls short of graduate degrees(Swaby, 1980).

8One United States operated nursing school in Jamaicaoperated by Seventh-Day-Adventists prepares the graduates withbaccalaureate nursing degrees. The University Hospital of theWest Indies has worked towards this goal by offering postgraduate studies.The current studentdiversity of ethnic groups.body comprises aThis is reflective of the manynationalities that make up the Caribbean population.evaluationof nursing educationamong this"ethnicThemix"creates a posture of ethnic cohesion, people motivation,survival strategies, communication patterns and leadershipstyles.Historical documentation should provide informationto the international community on nursing education by showinghow people of different races can work together objectivelywithout erunderstanding of how a health care and nursing andspiritualistic rites developed into a modern, scientificallybased educational program. Even when the Europeans came, theybrought no knowledge of germ theory or disease causation;hence, they were left to rely mainly on the crude techniquesof the aborigines, and the local natives taught them of themany benefits of herbal concoctions and the efficacy of herbalbaths(Williams, 1970).A greatrequired of these newcomers.deal of adaptation wasHistorically Caribbean areanursing education had not been well documented.The intent of

this study was to pull togetherthis information and toidentify the forces that influenced the development of nursingeducation in the Caribbean area.Conceptual FrameworkThis historical qualitative study will use the concept ofadaptation in investigating the changes in nursing educationin the Caribbean area over time.manencounterschangesinAccording to Rogers (1970),hisinternalandexternalenvironment to which he must adapt if he is to survive. Selye(1976) described the general adaptation syndrome and showedthe biological response to internal and external stressors,where man on a health continuum either survives or meets hisdemise (see Figure 1).AdHMHon ki NurafeipFigure 1.In liw En rii SpMMng CMbtMn Aran. Ad Midftnii.a KK. aid a L IWn. TTMaid ad. N«f» Yoric: Join Wlay and Sgnt. IWL Und by IGeneral Adaptation Syndrome Model.

10Adaptation may occur in the individual, the family orin groups, and occurs over the life span (Potter and Perry,1989).In order to maintain homeostasis, stressors must beprocessed effectively, individually or within the group (seeFigure 2 and Figure nwvwmn, NuraingEdiiciion.CuiTloul«RflvWon, NuraingOrganizatlorw 7\I!\7IIPerceived Situatiol- British BrutalityDocMonPiooen0Response Soioctiofi-Societal andReligious PressureAdMlaitofK Strass ResponM In Nursing Eduodion In tto Englsh SpeddnoCaribbMn flvea. Adeptod from J Ivanoevicti and M. MetlMon, Stress andWork: A Mani«erld P««pecii . Copyright 1980, by Soott. Forasman andCompany. Used by pandsaion.Figure 2.Process Model of Stress and Adaptation.

11HEALTH I11JC88 CONTINUUMuwii SSy?****'""* '*"**'"***'' *''*» amSX*roM.Figure 3 . Adaptation on the Life Continuum.In the Caribbean area, it appeared that both components(individuals and groups) in the form of nursing leaders,government officials, the church and communities combined tochange a hostile environment into one committed to universalhealth care issues.Other theorists of adaption(Roy, 1984; Hunt, 1975)advocate that in the health care arena demands are placed uponpatients psychologically, physiologically and sociologically.Hence, in this arena clients are in an adaptive mode is context, nursesclientsfailtobecomefunction

12independently. Nursing then has the responsibility to developa readiness for appropriate intervention to meet societalneeds.This readiness is achieved through nursing educationand through standards of nursing practice (Swaby, 1970).Inthis context nursing assists man to enhance the satisfactionof his needs and to achieve his highest degree of integratedfunctioning.Societal changes, however, transcend variousforms of metamorphosis.These dynamic alterations placegreater and greater demands on society.As a result the world has become a burgeoning arena ofscientific discoveries and technological rsing,nursingeducational strategies and scientific approaches to meet theneeds of a changing society (Dolan, 1958).While using thesestrategies nursing educators are involved in the teachinglearning process which creates dynamic interaction betweenteacher and learner.The teacher facilitates the acquisitionof knowledge and the generation of new knowledge about theconcepts of man, society, health and nursing.The intent isto produce a flexible environment, an open system which isconducive to meeting the ever changing needs of man in hisenvironment.Hunt (1975) supports the idea that necessity acts as anagent of change.He states:As we look back upon the history of inquiry itappears that a large proportion of the fundamentalbreakthroughs in science has been a result ofindividuals with a creative bent, originating a new

'/13interpretation which at the time of its formationseemed to most persons a complete violation ofcommon sense and of authoritative teaching,(p. 18)Nursing education in the Caribbean area seemed to haveplayed an intricate part in the arena of societal change whichis evidenced by its radical evolution.(1984), Hunt (1975), and Selye (1976)The theories of Royform the framework toexamine systems, change agents, the roles, and functions ofindividuals and some of the many behaviors that have affectedthe transition in nursing education.A review of the literature on nursing education in theCaribbean area revealed an evolution from spiritualistic ritesand rituals to a current modern educational system comparableto those of more developed countries.Some historians mayrecord only dates and events that functioned as the catalystfor this transition, but a more inquisitive investigation islikely to reveal an intricate adaptive process over time.Purpose of the StudyThe paucity of recorded information in the literaturecreates a need for an historical analysis of the processesthat are involved in the changes in nursing education in theCaribbean area.The purpose of this study was to present inchronological and cultural outline a clearer understanding ofthe adaptive forces and the cultural factors that affected thegrowth and development of nursing education in the Caribbean

14area. Attention also focused on the change from spiritism toprofessional nursing practice over indigenous cultures, selected Euro-Asian antecedents and wasThis was examined in the context of the influencesof contemporary world events upon the evolution of curricularchanges.Such a studyis important and timely since currenthistorical recordings deal with nursing development in moreadvanced countries, for example, the Florence Nightingale erain Great Britain and Dorothea Linde Dix's influence in theUnited States.These individuals were early proponents ofsound nursing education.More recently, nursing educatorshave emphasized the importance of an international orientationand a multicultural approach to nursing and nursing education(Abu-Saad, 1979; Masson, 1981; Grippando & Grippando, vemodalities among countries, but also to identify new ynon-existent or at best fragmented. This study should providea historical basis of the progressive growth and adaptation innursing education among the ethnic groups in the Caribbeanarea.

15One can assume that each ethnic group is likely to havemade its contribution to nursing education over time. landpeoples; he identifies them as having Portuguese, French,Spanish, Hindu,Lebanese, Venezuelan,American,Arabian,African Negro, Chinese, German and British backgrounds ghthavecontributed to the growth of nursing education and that shouldfacilitate the new emphasis on international orientation are:1.Congeniality among the races, evidenced by theabsence of segregation.(The opportunity to reside in a givenarea is more determined by financial status than by class orcaste. )2.The desire for group cohesion evidenced by theregional University of the West Indies founded toserve thehigher educational needs of the Caribbean Islands (Associationof Commonwealth Universities, 1965).These afforded higher standards of general education.Nursing and nursing education have also added their quota inthe formation of the Caribbean Nurses Organization which cameinto being in 1957 to link together all the professionalnursing organizations in the Caribbean Basin (Swaby, 1980, p.48).According to Bell and Oxar (1964), the British settlerswho came, as early as 1665, seemedto focus quickly on

16becoming self-sufficient in order to survive.They plantedcassava, sugar cane, tobacco, cotton, citrus and pineapple andused the wild growing pimento for spice.probablethat many healthIt is highlypractices and healthteachingapproaches were also used for survival as British, French andDutch adapted to the Caribbean area life style.In spite ofthese efforts the loss of lives to cholera and other tropicaldiseases were in epidemic proportions among the Europeans,while they remained endemic among the aborigines. The Arawakstaught the new settlers crude means of survival (Roberts,1940).It was well into the eighteenth century before fragmentedrecords of specific duties of the nurse appeared. Nurses werenow assigned to care for the sick (onpregnant women and their children.likely bytrialand errorinplantations) and forTheir practice was mostthe absenceoforganizedtraining.Today one views a changing Caribbean area in respect plines more closely resemble those of more developedcountries.(thanotherThis is supported by their higher passing ratethirdworldcountries)onthelicensureexamination in the United States. The consistent recruitmentof Caribbean nurses to the United States also seems to bereflective of a knowledge base comparable tothose of the

17host countries(Davy, 1965; Tulloch, 1965; "InternationalRecruitment," 1989).The unifying and cohesive forces seemed to reflect uniqueadaptation strategies among educational proponents, nursingand civic leaders, governmental forces, and political andsocial systems. Apparently these forces transcended the preChristian era described by Bullough and Bullough, 1984; Dietz,1963; Ellis and Hartley, 1984. The indigenous Arawaks likelyadded their contributions to the above mentioned forces ofunification and adaptationin what seemed to be an opensystem, as they selected chiefs or other leaders to manage thepeople's affairs and to perform the religious rites andrituals(Graves, 1965).The Caribs with their barbarousnature might also have left an indelible imprint on nursingand nursing education.The Spaniards came, followed by theFrench, Dutch and British.These groups were subsequentlyresponsible for the importation of many thousands of Africansinto the Caribbean (Williams, 1970).Telecommunication, computertechnologyhavecontributedtosystems and other modernanalreadyforcefulandorganized adaptive system in the area of nursing education.The Caribbean area has also been awarded national acclaim byits acceptance to membership in the International Council ofNurses in 1960. The historical documentation of the adaptiveevolution of nursing education over time in the Caribbean areawould not only broaden the Caribbean area nurses' historical

18perspective but also provide a resource for nurses of othercountries who travel to practice nursing in the Caribbeanarea.Today nursing history is a significant part of eanshould also be given a permanentspotnursingin thehistorical archives and should be added to nursing curricula.As the world becomes more interdependent and people interactmore closely it should be useful to document the history ofnursing education in the Caribbean area.Delimitations and Limitationsof the ment of nursing education primarily in the Englishspeaking Caribbean area from its discovery in 1498 until thepresent time. The study focused mainly on the Caribbeanregion.References to developments in the United States ofAmerica and several European countries were made to indicatethe influence of those developments on changes and adaptiveprocesses in the Caribbean political and nursing educational changes and adaptations.Developments in Trinidad and Tobago, Grenada, St. Kitts, St.Vincent, St. Lucia, Barbados, Dominica, Montserrat, Nevis,Jamaica, the Cayman Islands and Antigua were studied. Limitedcomparisons were made with Spanish, French and Dutch nursingeducational programs within the region.

19AssumptionsCertain assumptions were made in conducting this study.These assumptions were as follows:1.Both written and oral structured and unstructuredinterviews were conducted and the proper procedure was used.2.The journals and newspapers reviewed werereputable and contained correct information.3.The information in British literature closelyparalleled developments in the Caribbean area.Definition of TermsThe first three terms defined in this study are those ofthe National League for Nursing.They are used to showdifferences in Caribbean nursing preparation.These termsare:Baccalaureate Nursing Education,Diploma Nursing Education, andPractical/Vocational Nursing Education.The other terms defined should provide clarity and avoidambiguity in semantics.Baccalaureate Nursing aninstitution of higher learning. Generally students spend theinitial two years studying general education disciplines. Themajor in nursing is concentrated in the last two years ofupper division study. There is a strong theoretical base with

20related skills practice at this level. Nursing concentrationis on providing care to individuals and groups and workingwith health care teams. There is emphasis on research and onproviding students a sound foundation for graduate study. Thebaccalaureate graduate takes the same licensure examination asthe diploma and the associate degree graduate.Leaguefor NursinglistsThe Nationalseveral characteristicsofthegraduate from a baccalaureate program:Provide professional nursing care, which includes healthpromotion and maintenance, illness care, restoration,rehabilitation, health counseling, and education based onknowledge derived from theory and research.Synthesize theoretical and empirical knowledge fromnursing, science, and humanistic disciplines withpractice.Use the nursing process to provide nursing care forindividuals, families, groups, and communities.Accept respons

VI. CARIBBEAN NURSING EDUCATION IN TRANSITION. 62 Current Educational Programs 73 Nursing Schools in Jamaica 82 Nursing Schools in St. Lucia 83 Nursing Schools in Trinidad and Tobago 84 Caribbean Nursing Schools—Trends in Unification 85 Summary 87 VII. DEVELOPMENT OF PROFESSIONAL NURSING ORGANIZATIONS IN THE CARIBBEAN AREA 90