Transcription

May 2017Improving documentation attransitions of care for complexpatientsProfessor Elizabeth Manias, Professor Tracey Bucknall, Professor Alison Hutchinson,Professor Mari Botti and Ms Jacqui Allen from Deakin University (brokered by the SaxInstitute) have prepared this report on behalf of the Australian Commission on Safety andQuality in Health Care

Published by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health CareLevel 5, 255 Elizabeth Street, Sydney NSW 2001Phone: (02) 9126 3600Fax: (02) 9126 3613Email: mail@safetyandquality.gov.auWebsite: www.safetyandquality.gov.auISBN: 978-1-925224-94-8 Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care 2017All material and work produced by the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality inHealth Care is protected by copyright. The Commission reserves the right to set out theterms and conditions for the use of such material.As far as practicable, material for which the copyright is owned by a third party will be clearlylabelled. The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care has made allreasonable efforts to ensure that this material has been reproduced in this publication withthe full consent of the copyright owners.With the exception of any material protected by a trademark, any content provided by thirdparties, and where otherwise noted, all material presented in this publication is licensedunder a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 InternationalLicence.Enquiries regarding the licence and any use of this publication are welcome and can be sentto communications@safetyandquality.gov.au.The Commission’s preference is that you attribute this publication (and any material sourcedfrom it) using the following citation:Manias E, Bucknall T, Hutchinson A, Botti M, and Allen J. Improving documentationat transitions of care for complex patients. Sydney: ACSQHC; 2017The content of this document is published in good faith by Australian Commission on Safetyand Quality in Health Care (the Commission) for information purposes. The document is notintended to provide guidance on particular health care choices. You should contact yourhealth care provider on particular health care choices.This document includes the views or recommendations of its authors and third parties.Publication of this document by the Commission does not necessarily reflect the views of theCommission, or indicate a commitment to a particular course of action. The Commissiondoes not accept any legal liability for any injury, loss or damage incurred by the use of, orreliance on, this document.2

PrefaceThe Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (the Commission) iscommitted to improving and supporting effective communication with patients, carers andfamilies, and between clinicians and multidisciplinary teams.In Australia there are an increasing number of people who have complex and chronichealthcare needs, and it is common for their care to be provided by a number of differentclinicians and health providers, across many different settings. This includes care deliveryacross hospitals, private rooms, general practices and other locations.The points of handover when patients move between clinicians are known as ‘transitions ofcare’, and these are recognised as times of high risk for patients as there is an increasedrisk of information being miscommunicated or lost.Effective communication between clinicians and across multidisciplinary teams when thesetransitions occur is essential to ensuring safe, continuous and coordinated care. Onemechanism to support effective communication and safeguard patient safety acrosstransitions is to ensure that the information available to clinicians is clear, current, relevant,accurate and complete.To develop a better understanding of what information should be available to clinicians attransitions of care, the Commission engaged Deakin University to conduct a rapid literaturereview on improving documentation at transitions of care for patients with complexhealthcare needs. The review focuses on whether there is evidence about the: safety and quality issues related to poor documentation for complex patients attransition of careinformation that needs to be recorded, at a minimum, to support safe transitions ofcareform or structure of the documentation required at different transitions of care.Key findingsThe review finds there is strong evidence that poor documentation of information attransitions of care is a key safety and quality issue for patients with complex healthcareneeds. Poor documentation can lead to adverse events, including: higher rates of readmission to hospitalfailure to follow up after hospital dischargeincreased costs related to inadequate or reduced care coordinationlack of availability of important diagnostic resultsmedication errors, including missed medications, dose errors and emergencymedications being ceased accidentally or missed.The review identifies common information elements that at a minimum should be available toclinicians to support effective communication at transitions of care for patients with complexhealthcare needs. The minimum information elements identified in the report are: patient detailsfamily and carer support detailsdocument author and location3

document recipients and locationencounter detailsproblems and diagnosisclinical synopsisrelevant pathology and diagnostic imaging investigationsclinical interventionsmedicationsallergies and adverse drug reactionsalertsarranged servicesrecommendations for managementinformation provided to patient, carer and familynominated primary health providers.The authors recognise that patients’ needs may vary. Clinicians should therefore consider apatient’s individual requirements, type of transition of care, and tailor the information to thespecific needs of the patient. The review also categorises the information that should beavailable for eight specific complex patient groups. The report also acknowledges there isinsufficient evidence about the minimum information content required for complex patientsfrom specific demographic backgrounds, including people with a first language other thanEnglish, refugees, low-income earners and those from rural and remote areas.The structure and form of documentation is important. There is evidence that tools,checklists and templates can be a helpful guide, and act as effective prompts for clinicians toidentify what needs to be documented, and the key areas to consider when documentinginformation.The report found that the use of inconsistent abbreviations and lack of standardisedterminology in the healthcare record can affect how documented information is understood.This can result in information being in some cases misinterpreted.Recommendations of the reportThe authors of the report recommend a set of common information elements that, at aminimum, should be available to clinicians when transferring care for patients with complexhealthcare needs. When documenting clinical information, the report recommends thatclinicians consider the particular needs of their patients, the type of transition of care, andtailor the information accordingly. Further research on the minimum information contentrequired for complex patients from specific demographic backgrounds was alsorecommended.The report recommends standardised, structured recording of information while maintainingflexibility to communicate patient care across transition points. It is proposed that the tools,checklists and templates identified in the review could be helpful to support documentation ofclinical information, within the particular clinical setting for which they have been developed.The report recommends the need for standardised language and terminology and that anational list of approved abbreviations for use in documentation be developed.4

Next steps for the CommissionThe Commission will consider the report’s recommendations. The Commission will usethese findings to inform future work on improving clinical communication at transitions ofcare.Findings of this review will inform the development of guidance materials and resources tosupport consumers, health service organisations and clinicians communicate safely attransitions of care. This will also support implementation of the National Safety and QualityHealth Service (NSQHS) Standards (second edition).Actions within NSQHS Standards (2nd ed.) recognise the importance of documenting clinicalinformation in the healthcare record, and its role in supporting effective communication andsafe care. These actions are designed to protect the public from harm and improve thequality of health service provision.5

IMPROVING DOCUMENTATION ATTRANSITIONS OF CARE FOR COMPLEXPATIENTSFinal reportPrepared by Deakin University (brokered by the SaxInstitute) on behalf of the Australian Commission onSafety and Quality in Health CareInvestigators: Professor Elizabeth Manias, Professor Tracey Bucknall,Professor Alison Hutchinson, Professor Mari Botti, Ms. Jacqui Allen

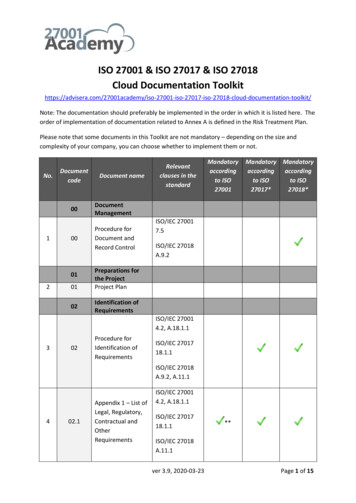

ContentsReport Summary . 8Background and introduction. 17Description of method used for searching and selecting research papers . 18Question 1: What is the evidence regarding safety and quality issues relating to poordocumentation for complex patients at transitions of care? . 22Question 2: What is the evidence, including best practice and guidelines, regarding theminimum information content requirements for recording information at different transitions ofcare?. 27Question 3: What is the evidence regarding the form or structure of the documentationrequired at different transitions of care? . 50References . 65Appendix 1: Included studies (N 59). 70Appendix 2: Form, structure, information content, study findings and quality of evidence ofincluded papers (N 59) . 82List of tablesTable 1: Identified tools, checklists and templates providing structure for documentation fordifferent transitions of care . 12Table 2: Search terms and major subject headings and text words with truncation (*) forelectronic database searches. 18Table 3: Combination of search terms for accessing grey literature in Google Scholar . 19Table 4: Papers derived from bibliographical databases . 20Table 5: Common elements for all complex patient types . 28Table 6: Minimum information content for older patients . 30Table 7: Minimum information content for hospitalised children . 33Table 8: Minimum information content for patients with mental illness . 35Table 9: Minimum information content for patients with multiple comorbidities . 37Table 10: Minimum information content for patients across the peri-operative pathway . 40Table 11: Minimum information content for patients admitted to intensive care . 44Table 12: Minimum information content for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients . 46Table 13: Minimum information content for palliative care patients. 48Table 14: Evidence of standardised tools, checklists and templates . 517

Report SummaryThe Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care, through the Sax Institute,appointed researchers from Deakin University to conduct a review on improvingdocumentation at transitions of care for complex patients.The review focuses specifically on complex patients undergoing transitions of care where thetransition points include admission, discharge, transfer of care across settings, referrals,requests and follow-up. More specifically, the review examines documentation involvingtransitions to, within and from acute care settings. The focus is on communication acrossmultidisciplinary teams, moving beyond clinical handover at shift-to-shift change.The content is considered in terms of three review questions:1. What is the evidence regarding safety and quality issues related to poordocumentation for complex patients at transitions of care?2. What is the evidence, including best practice and guidelines, regarding the minimuminformation content requirements for recording information at different transitions ofcare?3. What is the evidence regarding the form or structure of the documentation required atdifferent transitions of care?A total of 59 papers were included in the review. The most common research designs usedwere tool or guideline development and evaluation, and pre- and post-intervention designs.Other research designs used included longitudinal case study or cohort designs, qualitativeinterview or observational designs, retrospective clinical audits, prospective clinical audits,and survey designs. Only two studies involved the conduct of randomised controlled trials.Most studies were completed in the United States (n 23), followed by Australia (n 15) andCanada (n 11). The remaining studies were conducted in countries situated in Europe andAsia.What is the evidence regarding safety and quality issues related topoor documentation for complex patients at transitions of care?There was extensive evidence that poor documentation led to different types of adverseevents in complex patients, which included the following: high readmission rates to hospitalfailure to follow up after hospital dischargeincreased costs related to care coordinationlack of referrals to community service providersincreased presentations to emergency departments and increased lengths of hospitalstaysub-optimal management of patients’ conditions, inadequate assessment offunctional state and inadequate detection of preventable complications in intensivecare units8

sub-optimal management of patients’ ventilation and an increased incidence ofaccidental withdrawal of breathing tubes in intensive care unitslack of availability of important diagnostic resultsincreased risk of intra-operative complications, such as high lactate levels, highglucose levels thereby requiring an insulin infusion, low blood pH levels, and highblood carbon dioxide levelsmedication errors, including delays and omission of antibiotics, missed medicationsand dose errors, and emergency medications being ceased accidently or missedpatient deterioration requiring medical emergency team calls and patient falls.Gaps in evidence exist in terms of specific demographic characteristics of complex patients.Such gaps relate to people of non-English speaking backgrounds, people seeking or whohave been granted refugee status, homeless people, people with mental illness and peoplewith drug and alcohol disorders. Other vulnerable groups for whom evidence gaps areapparent include economically disadvantaged individuals comprising those with low incomesand those who are unemployed. Gaps also exist in relation to patients and healthcaresettings in rural and remote areas.What is the evidence regarding the minimum information contentrequirements for recording information at different transitions ofcare?The evidence was examined to determine common elements for the minimum informationcontent that should be available at any transition of care point, as well as to determinevariations of this information. The following common elements were identified for all complexpatient types: patient detailsfamily and carer support detailsdocument author and locationdocument recipients and locationencounter detailsproblems and diagnosisclinical synopsisrelevant pathology and diagnostic imaging investigationsclinical interventionsmedicationsallergies and adverse drug reactionsalertsarranged servicesrecommendations for managementinformation provided to patient, carer and familynominated primary health providers.Evidence for minimum information content was also identified for complex patient groupingsincluding:9

older patientshospitalised childrenpatients with mental illnesspatients with multiple comorbiditiespatients moving along the peri-operative pathwaypatients admitted to intensive careAboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patientspalliative care patients.Minimum information for these complex patient groups included information in addition to thecommon elements.For older patients, examples of additional content information included: clinical synopsis: resuscitation code status, presence and the nature of pain, andsocial and lifestyle history – psychosocial assessmentmedications: alterations for renal and liver insufficiency, and plans for deprescribingalerts: presence of geriatric syndromes, such as incontinence, falls, functionaldecline, delirium, dementia and frailty.For hospitalised children, examples of additional content information included: information provided to patients, carers and family: child involvement in care, healthliteracy of child in relation to growth and development, parental involvement in careand need for an interpreterclinical synopsis: interpretation of relevant observations (behaviour – playing,sleeping, irritability, lethargic; cardiovascular state – skin and mucus membranecolour, heart rate and rhythm; respiratory state – rate, accessory muscle use,grunting).For patients with a mental illness, examples of additional content information included: clinical synopsis: assessment of drug and alcohol consumption, interpretation ofrelevant observations, including mental health state and blood pressure, social andlifestyle history (psychosocial assessment, interpretation of relevant pathology anddiagnostic imaging, including blood glucose and blood cholesterol levels)information provided to patient, carers and family: family and carer support.For patients with multiple comorbidities, examples of additional content information included: medications: methods to facilitate administration, dose administration aids andcrushing tablets, medication adherence with prescribed regimeninformation provided to patients, carers and family: dietary management, activityability and goals, allied health care involvement, home assistance and communitysupport, rehabilitation program, outpatient or outreach service follow-up.For patients moving along the peri-operative pathway, examples of additional contentinformation included: information provided to patients, carers and family: informed consent10

post-operative care: evaluation of wound, coughing and deep breathing, instructionsfor diet, medications, pain relief, wound care, stoma care, wires and drain care.For patients admitted to intensive care, examples of additional content information included: problems and diagnoses: reason for admission to intensive care, management ofcomorbidities by external health care teamsclinical interventions: endotracheal tube and cuff, ventilation and oxygenationmanagement, intravenous and arterial lines, ulcers of the skin and gastrointestinaltractinformation provided to patients, carers and family: family and carer counselling,preferences for receiving treatment if patient becomes incapacitated, patient’sdecision about life-saving treatment.For Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander patients, examples of additional content informationincluded: clinical synopsis: interpretation of relevant observations, including vital signs,neurological state, and oxygenation, social and lifestyle history (psychosocialassessment, assessment for drug and alcohol consumption, assessment fordepression, assessment of patient diet)recommendations for management: consultation with Aboriginal and Torres StraitIslander health worker, referral to rehabilitation program, outpatient or outreachservice follow-up.For palliative care patients, examples of additional content information included: clinical synopsis: resuscitation code statusinformation provided to patients, carers and family: preference for care, preferredplace of death.What is the evidence regarding the form or structure of thedocumentation required at different transitions of care?All 59 research papers were examined for evidence of standardised tools, checklists andtemplates that provide the structure of documentation for different transitions of care. Therewere 14 identifiable tools, checklists and templates in the papers. These provide helpfulinformation to guide health professionals in documenting patient care at transition points,and can be used as prompts for their documentation, which can be tailored andindividualised to suit specific patients in their care.Inconsistent use of abbreviations in healthcare records and the lack of standardisedlanguage and terminology were also identified as key safety and quality issues whenconsidering the form of documentation. This affected the readability and interpretability ofdocuments.11

Table 1: Identified tools, checklists and templates providing structure fordocumentation for different transitions of careName of tool, checklistsand templatesDescription of toolUseBEFORE YOU ADMIT toolPolypharmacyGoals of careAreas to check beforeadmission of an olderpatientDeliriumFrailtyAspirationFallsBOOST (Better Outcomes forOlder adults through SafeTransitions) tools8P Risk assessment (problemmedications, psychological,principal diagnosis,polypharmacy, poor healthliteracy, patient support, priorhospitalisation in last sixmonths, palliative care)Six tools that can be usedduring care transitions forolder peopleGeneral assessment ofpreparednessWritten discharge instructionsPreparation to AddressSituations Successfully(PASS)Discharge Patient EducationTool (DPET)Teach backC-CEBAR (mnemonic)C - Contact of casephysiotherapist of acutehospitalC - Contact details of patientManagement of complexpatients byphysiotherapists acrosstransitionsE - Expectations of receivingphysiotherapist for requiredrehabilitation therapyB - Background and historyA - Assessments and functionR - Responsibilities and riskmanagement, including safetyprecautions and unanticipatedpatient's responseChecklist of Safe DischargePracticesHospitalPrimary careMedication safetyAspects to consider indischarge of complexpatientsFollow-upHome care12

Name of tool, checklistsand templatesDescription of toolUseCommunicationPatient educationD-SAFE (DischargeSummary Adapted to theFrail Elderly Patient)Medical discharge summaryDEFAULT (mnemonic)D - Do not resuscitate (DNR)status clearDischarge prescriptionsummaryE - Endotracheal tube and cuffis safeF - Fluid strategy and feedingplanAspects to consider fordischarge of frail, olderpatients to and fromacute care settingsAspects to considerbetween different careteams for communicationabout patients inintensive careA - Agreed analgesia andsedationU - Ulcer of the skin and gutL - Lines outT - Tidal volumes less than 8ml/kgINTERACT II, Stop andWatch Tool (mnemonic)S - Seems different than usualT - Talks or communicateslessO - Overall needs more helpP - Pain – new or worsening;participated less in activitiesAspects to consider intransfer of older peoplebetween residential agedcare facilities andemergency departmentsA - Ate less than usualN - No bowel movement inthree days; or diarrhoeaD - Drank lessW - Weight changeA - Agitated or nervous morethan usualT - Tired, weak, confused, ordrowsyC - Change in skin colour orconditionH - Help with walking,transferring, toileting morethan usual13

Name of tool, checklistsand templatesDescription of toolUseI-PASS (mnemonic)I - Illness severity; stable,needs watching, unstableAspects to consider whenpaediatric patients movebetween acute care unitsand intensive care unitsP - Patient summary; summarystatement, events leading toadmission, hospital course,ongoing assessment, planA - Action list; to do list, timeline and ownership; know whatis going on, plan for whatmight happenS - Situation awareness andcontingency planningS - Synthesis by receiver;receiver summarises what hasbeen heard, asks questions,restates key actionsMDS for PICU (MinimumData Set for PaediatricIntensive Care Unit)Identification bar highlightspatient’s trajectory in red,yellow or greenAllergiesAspects to consider whendifferent care teamsmanage paediatricpatients in intensive careMedicationsPertinent patient historyBody system areas12-hour follow-up planContingency planRead-back from sender toreceiverMind the Gap ToolHealth professional-relatedcharacteristicsTransitional care deliveryprocessPatient-related characteristics:adolescentsAspects to consider in thetransition of adolescentswith chronic conditionsfrom paediatric to adulthospital and rehabilitationPatient-related characteristics:parents7Ps flowchartP - Problem medicationsP - Punk (depression)P - Principal diagnosesAspects to consider whenolder patients aredischarged from acutecare settingsP - PolypharmacyP - Poor health literacyP - Patient supportP - Prior hospitalisation14

Name of tool, checklistsand templatesDescription of toolUseRAPaRT (Rapid AssessmentPrioritisation and ReferralTool)Previous regular helpHospitalised in past six monthsTo identify when referralto an allied healthprofessional is needed forcomplex patientspresenting to emergencydepartmentsMore than three medicationsprescribedWalking aids or assistanceSomeone else shoppingLost weight recently, eatingpoorlyFalls in the past six monthsPSOST (Providers’ Signoutfor Scope of Treatment)Brief history of present illnessPast medical historyResuscitation code statusSignificant laboratory ordiagnostic test results, ‘‘to do’’list of laboratory tests andproceduresAspects to consider byhealth professionals forpatients receivingpalliative careCare plan3-Ds Checklist(Diet, Drugs, Discharge plan)DietProton pump inhibitor useHelicobacter Pylori eradicationregimenNon-steroidal antiinflammatory drug useAspects to consider byhealth professionals afterpatients’ dischargefollowing endoscopy forupper-gastrointestinalbleedingComplete blood countDischarge plan timeFollow-up in gastroenterologyclinic, general practitioner orendoscopy clinicConclusionThe review has identified the importance of flexible standardisation and structureddocumentation. Three review questions have been addressed.There is evidence that poor documentation is a safety and quality issue for complex patientsat transitions of care.There is evidence of the common elements that should be included as minimum data whenrecording information for complex patients at transitions of care. Minimum data requirementsvary for various subgroups of complex patients. Health professionals need to consider theparticular needs of complex patients, and to tailor the minimum data accordingly.15

The structure of documentation is important, and tools, checklists and templates can act aseffective prompts for identifying key areas to consider. It is recommended that these tools,checklists and templates are used in practice, within the particular clinical settings for whichthey have been developed.There are gaps in evidence regarding complex patients with specific demographiccharacteristics, especially in terms of socioeconomic and cultural aspects of vulnerability. Itis suggested that further research should be conducted in these areas.16

Background and introductionIn April 2016, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care appointedresearchers from Deakin University to review and report on the evidence regarding safetyand quality issues, minimum information content requirements and the tools and strategiesfor documentation at transitions of care for complex patients. The aim of this review is toinform the future development of policies and other resources relating to documentation toassist health services, health professionals, patients and their families. This report containsthe findings of the integrative review, a summary of the evidence base of tools, checklistsand templates used to convey information around transitions of care, and concludes with keyrecommendations.AimThe aim of this review was to examine documentation at transitions to, within and from acutecare settings. The content is considered in terms of the three review questions:Question 1: What is the evidence regarding safety and quality issues related to poordocumentation for complex patients at transitions of care?Question 2: What is the evidence, including best practice and guidelines, regarding theminimum information content requirements for recording information at different transitions ofcare?Question 3: What is the evidence regarding the form or structure of the documentationrequired at different transitions of care?The following definitions have been used for the purpose of the review.Complex patients comprise patients with multiple care needs who are served by multipleproviders, who have several comorbidities, and who are possibly vulnerable. For thepurpose of this review, these are patients who access acute care settings at some stage.Aside from those with multiple care needs, complex patients are people with disa

safety and quality issues related to poor documentation for complex patients at transition of care information that needs to be recorded, at a minimum, to support safe transitions of care form or structure of the documentation required at different transitions of care. Key findings